Following Essex at Agincourt on Saturday 31 October 2015, archivist Katharine Schofield has written a summary of the involvement of Essex noblemen in this famous battle.

The Battle of Agincourt was fought on St. Crispin’s Day, 25 October 1415. It was perhaps the most famous battle of the Hundred Years’ War, when the outnumbered English forces defeated the French, with the English longbow archers making a decisive contribution defeating the French cavalry. The battle was immortalised in the 16th century by William Shakespeare in the play Henry V (written c.1599) and by Michael Drayton in his poem Fair stood the wind for France (c.1605).

As Prince of Wales Henry V had fought the Welsh and it was not long after he succeeded his father Henry IV I in 1413 that he sought to raise an army against the French and renew the claims of his great-grandfather Edward III to the French crown. In December 1414 Parliament granted him a tax for war against the French. Henry V and his army landed in northern France on 13 August 1415.

The campaign started with the siege of Harfleur. The town did not surrender until 22 September, by which time the summer, and the best conditions for military campaigns, was nearly over. The English had also suffered casualties during the siege, notably to dysentery and other diseases.

Among those who died at Harfleur was Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk and lord of the manors of Langham and Nether Hall in Gestingthorpe. His son Michael, 3rd earl, was to die a month later at Agincourt.

Another man with Essex connections, Lewis John, was among those invalided home from Harfleur; he went on to serve as sheriff of Essex, 1416-1417 and 1420-1422. He originated from Wales and had come to London, presumably to make his fortune. By the time he died in 1442 Sir Lewis John owned land in a number of counties, including West Thurrock and East and West Horndon in Essex.

Having gained only one town for all the money spent raising an army, Henry V was reluctant to return to England and so set off to march to the English garrison at Calais, reasserting his hereditary claim to lands in northern France. The French army that had been unable to save Harfleur was now ready to face the English. Henry’s forces had been weakened by illness, had inadequate supplies of food and had marched 260 miles in two and a half weeks, but did not want to delay battle in case the French were able to bring up more reinforcements.

The two sides faced each other; as the French cavalry advanced they were trapped in muddy ground and caught in the deadly fire of the English archers and were unable to advance on the English forces. Among the French casualties were the constable and admiral of France, the master of the royal household, and the Dukes of Brabant, Alençon and Bar. Around 1500 noblemen were taken to England as prisoners, including Charles, Duke of Orleans, the Duke of Bourbon, Jean Le Maingre, Marshal of France and the Count of Eu.

The battle itself achieved very little immediately. Henry continued his march on Calais and then returned in triumph to England. However, the defeat and death or capture of so many of the French nobility meant that when Henry returned in 1417 he was able to capture towns and castles across northern France.

In 1420 the Treaty of Troyes was signed. Henry married Katherine, daughter of Charles VI of France and was declared the regent and heir of the king. Henry’s triumph was short-lived. He died in 1422 leaving his nine month old son Henry VI as king. He was crowned king of England in 1429 and king of France at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in 1431. However, Charles VI’s son Charles VII was able to regain French territory, and by 1453 English possessions in France were reduced to Calais. Henry VI was ultimately to lose his throne to Edward IV in the Wars of the Roses.

A number of Essex lords had raised men from their lands to form part of the king’s army. It is likely that not only the lords, but some of the men in their retinues would have come from the county. One of the great lords present was Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick depicted in the battle by Drayton as ‘Warwick in blood did wade’. Although his lands were mostly elsewhere, he was lord of the manor of Walthamstow.

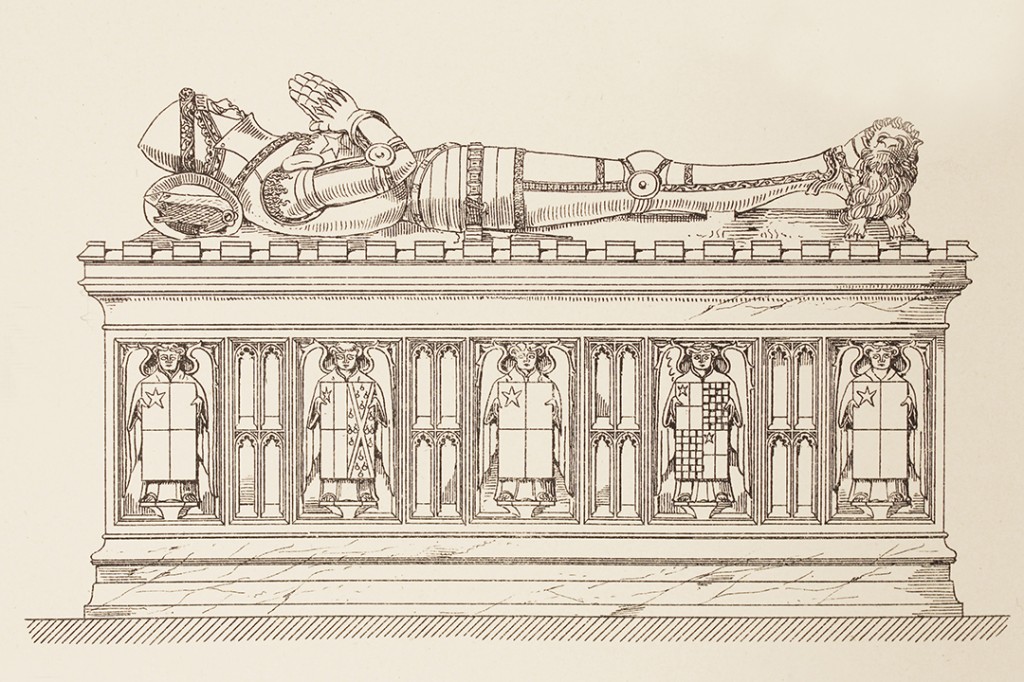

Richard de Vere, 11th Earl of Oxford was almost the same age as the king, and they had both served Richard II as pages. His grandfather John, the 7th earl, had fought at Crécy and Poitiers in the reign of Edward III. He supplied 39 men-at-arms and 60 archers to the campaign. He commanded the rear of the army as it marched from Harfleur, and took a prominent role in the battle, capturing Jean, Sire de Ligne. Drayton wrote that ‘Oxford … cruel slaughter made’. He was rewarded for his role in the battle by becoming a knight of the Garter in May 1416, in place of Edward, Duke of York, one of the notable English casualties of the day. Oxford died in 1417 and was buried at Earls Colne.

The Bourchier family originated from Halstead and Sible Hedingham and served against the French at various times during the Hundred Years’ War. Sir William Bourchier, a justice of the peace in Essex, fought at Agincourt and also on the 1417 expedition. He had inherited lands at Little Easton, Broxted and Aythorpe Roding from his mother Eleanor de Lovayne and was also lord of the manor of Wix. In 1419 Henry V rewarded him with the title Count of Eu for his service in France.

Humphrey, 6th Lord FitzWalter died aged only 16 while on campaign. His younger brother and successor William, baptised at Woodham Walter, also served on the campaign and was present at Agincourt. He went on to campaign in France in later years and drowned returning to England in 1431. He was buried in Little Dunmow.

As well as the great lords present at Agincourt, a number of Essex gentry also fought in the battle. Sir Thomas Erpingham was in charge of the archers who had such a devastating effect on the course of the battle. He is said to have launched the archers’ attack by throwing his baton into the air as a signal to fire and shouted ‘Now Strike’. His lands were in Norfolk, although he did hold four Essex manors through his wife, including Little Oakley. His retinue of 20 men at arms and 60 mounted archers included Sir Walter Goldyngham who was present at the battle. The Goldynghams had first been granted a manor in Bulmer by Robert Malet, one of the tenants-in-chief listed in Domesday Book. This manor came to be known as Goldingham Hall.

Sir Nicholas Thorley, lord of the manor of Bobbingworth fought in the retinue of Henry’s brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. He survived the battle and went on to serve as sheriff of Essex 1431-1432 and later married the earl of Oxford’s widow Alice without royal permission. For this omission Thorley was imprisoned in the Tower for three years and his wife had to pay a fine of one year’s value of all her lands.

Other Essex gentry present at the battle were Sir John Tyrell of Heron Hall in East Horndon who was also part of the Duke of Gloucester’s retinue. Having survived the battle he went on to serve as sheriff of Essex and Hertfordshire in 1423, speaker of the House of Commons and was treasurer to Henry VI’s household. He married Alice de Coggeshall, daughter and co-heiress of Sir William de Coggeshall of Little Coggeshall.

The Waldegrave family acquired the manor of Navestock in the 16th century. Sir Richard Waldegrave, present at Agincourt, held the manor of Wormingford by service of 10d. ward penny (a sum paid for watching a castle) per annum. Others who served included Robert Helyon of Helions Bumpstead with six esquires and three mounted archers and Sir William Mountneney of Mountnessing. Sir John Hevenyngham, lord of the manors of Little Totham, Eastwood, Fleet Hall in Sutton and Goldhanger fought in the retinue of the Earl of Norfolk.

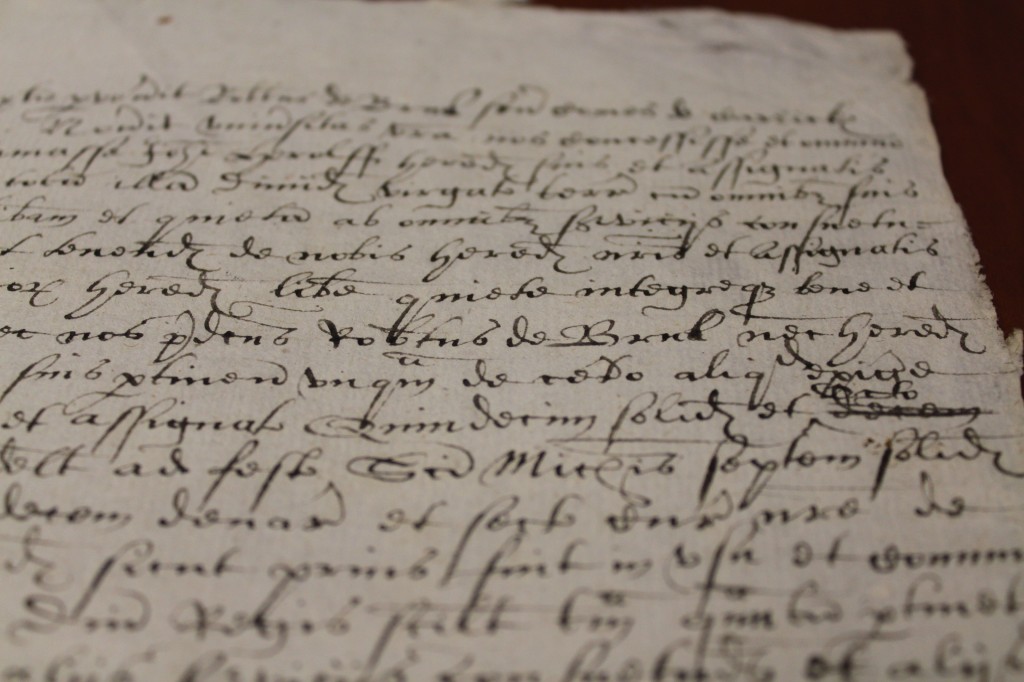

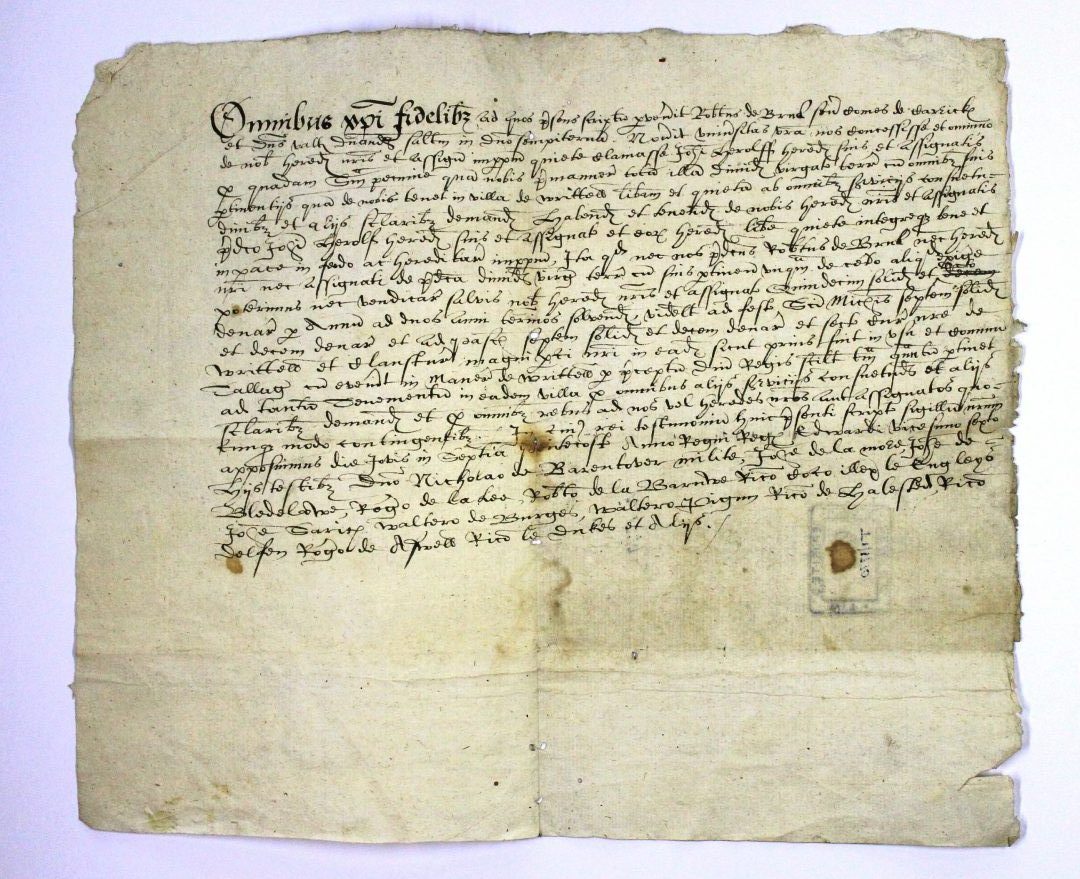

Seals attached to D/DAy T1/13, from left to right: monogram, RW; an ermin’s tail in a crescent moon: legend, Solu[m] deo honor [et] gloria; arms and crest of Waldegrave: legend, S’ Ricardi de Waldegrave