Archive Assistant Robert Lee takes a look at one of the many small interactions that went into the creation and updating of the Ordnance Survey maps that we know and love.

Between 1791 and 1845, The Board of Ordnance had commissioned a mass triangulation survey of Great Britain; endeavouring to produce a “grand meridian line, thro’ the whole extent of the Island” (Roy). Such an endeavour would fine tune the latitudes and longitudes of the country, and allow for more accurate mapping. Approximately 300 obelisks, all ostensibly placed on some high point, like hills and mountains, were plonked around Britain, upon which triangulation would be undertaken. Not all of these points were natural, however.

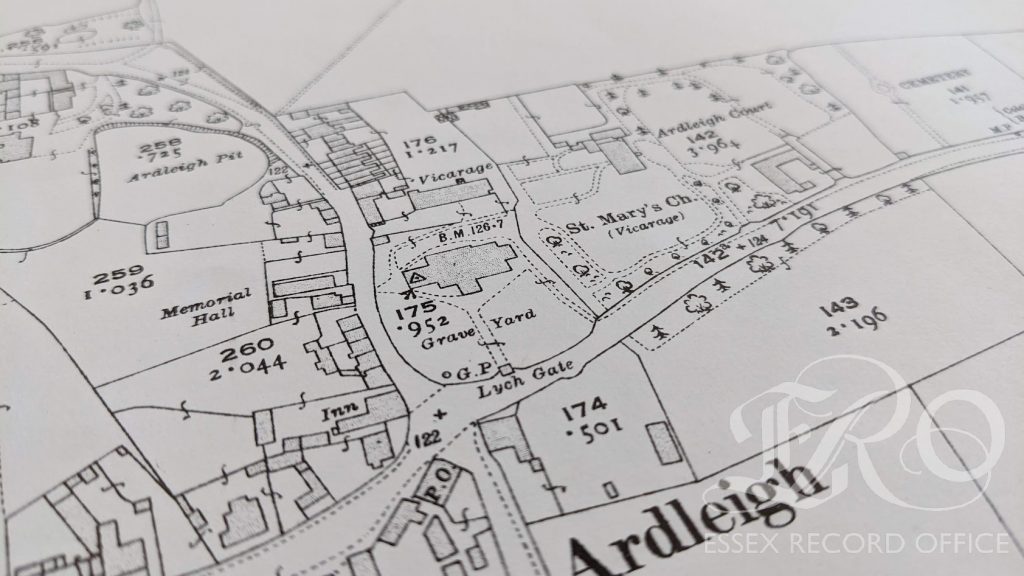

I have uncovered a letter (D/P 263/6/26), sent on behalf of the Ordnance Survey Office, to a church in Ardleigh, Essex. The letter warns vehemently, yet with a hint of irony and sympathy, of the need to occupy the church’s roof once more for a re-triangulation survey in 1938. “[I]t will be necessary”, the correspondent expounds, “to carry out most of the observations by night from and to small electric projectors”.

There is something beautifully modernist about the vignette of several Ordnance Surveyors perched atop a church tower in a small county parish, operating a heavy laser projector between old stone pinnacles. No more apparent is the imminent crossover between old-time religion and contemporary science.