The 26th October is the feast day of St Cedd, it is also Essex Day. Over on our social media we have taken you on a treasure trail of where you can find Seaxes here at the Essex Record Office. The three Seaxes will be familiar to many Essex residents as part of the logo for Essex County Council and on a red background, as their Coat of Arms. But what is a Seax and why has Essex taken it as their symbol? Customer Service Team Lead, Edward Harris delves deeper.

Essex County Council was first granted it’s Coat of Arms by the College of Arms on the 15th July 1932 comprising:

Gules, three Seaxes fessewise in pale Argent, pomels and hilts Or, pointed to the sinister and cutting edges upwards.

The somewhat archaic terms used by the College of Arms can be translated to:

Red, three Seaxes horizontal in pale silver, pommels and hilts gold, pointed to the viewers right with cutting edges upwards.

So now we know what the official Coat of Arms should look like, but we are still not given any clues as to the origin of the name Seax for the bladed weapons shown on the Coat of Arms.

The seax, (or scramasax as it is more usually called by archaeologists) is a weapon used by the Anglo-Saxon people who had displaced, at least culturally the Romano-British inhabitants of the British Isles in the 5th and 6th Centuries. The earliest evidence for the use of a Seax is from the mid 5th Century, though they would still see use in one form or another into the late 13th Century. The term Seax covers a whole family of germanic blades which varied widely in size and shape. The Anglo-Saxons widely used the distinctive broken back seax which varied in length from 30″ to as short as a few inches and, for most, it was probably a utility or defensive knife rather than a weapon of war.

Iron seax, with a straight cutting edge and sharply angled back, the tang offset from the blade.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

It is from the Saxons that the County of Essex (along with the Ancient County of Middlesex) takes its name. The Boundary of Essex still resembles that of the Saxon Kingdom of Eastseaxe. And it is from this Saxon heritage that Essex adopted the seax as it’s symbol.

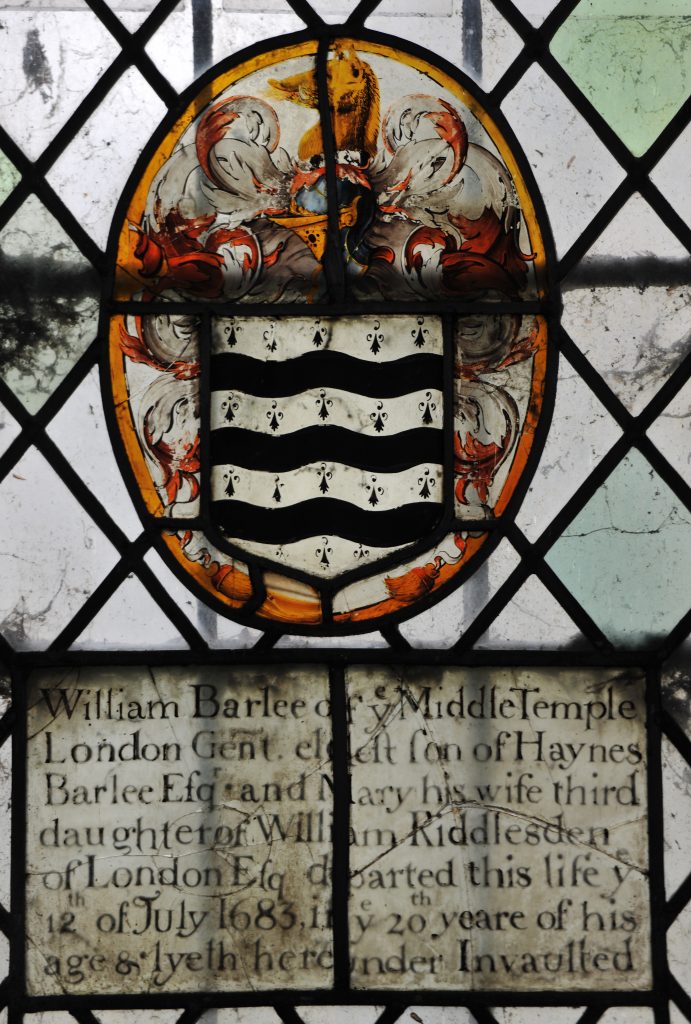

The Coat of Arms itself was in regular use well before the grant from the College of Arms in 1932 albeit unofficially. It is likely that the Arms were first assigned to the Saxon Kings of Essex by the more romantic minds of the Late 16th and early 17th Century, as the heraldry in any recognisable sense would not exist until the 12th Century.

One of the earliest mentions of a coat of arms is by Richard Verstegan who writes in 1605 of the East Saxons having two types of weapon, one long and one short. The latter being worn “privately hanging under their long-skirted coats” and “of this kind of hand-seax Erkenwyne King of the East Saxons did bear for his arms, three argent, in a field gules”

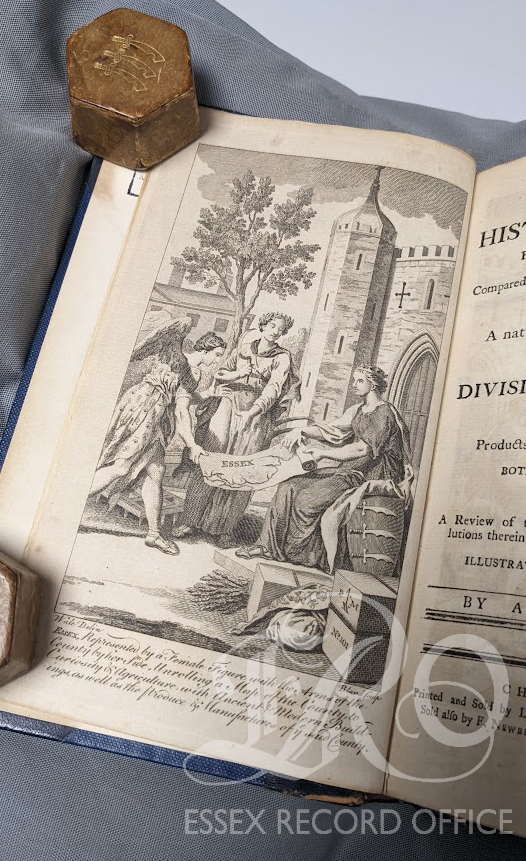

Peter Milman’s History of Essex 1771 (LIB/942.67 MUI1-6)

By the 18th Century the use of the Arms seems commonplace, in 1770, Peter Muilman published the first volume of his History of Essex. The frontispiece shows a shield with the three seaxes although with an unfamiliar shape.

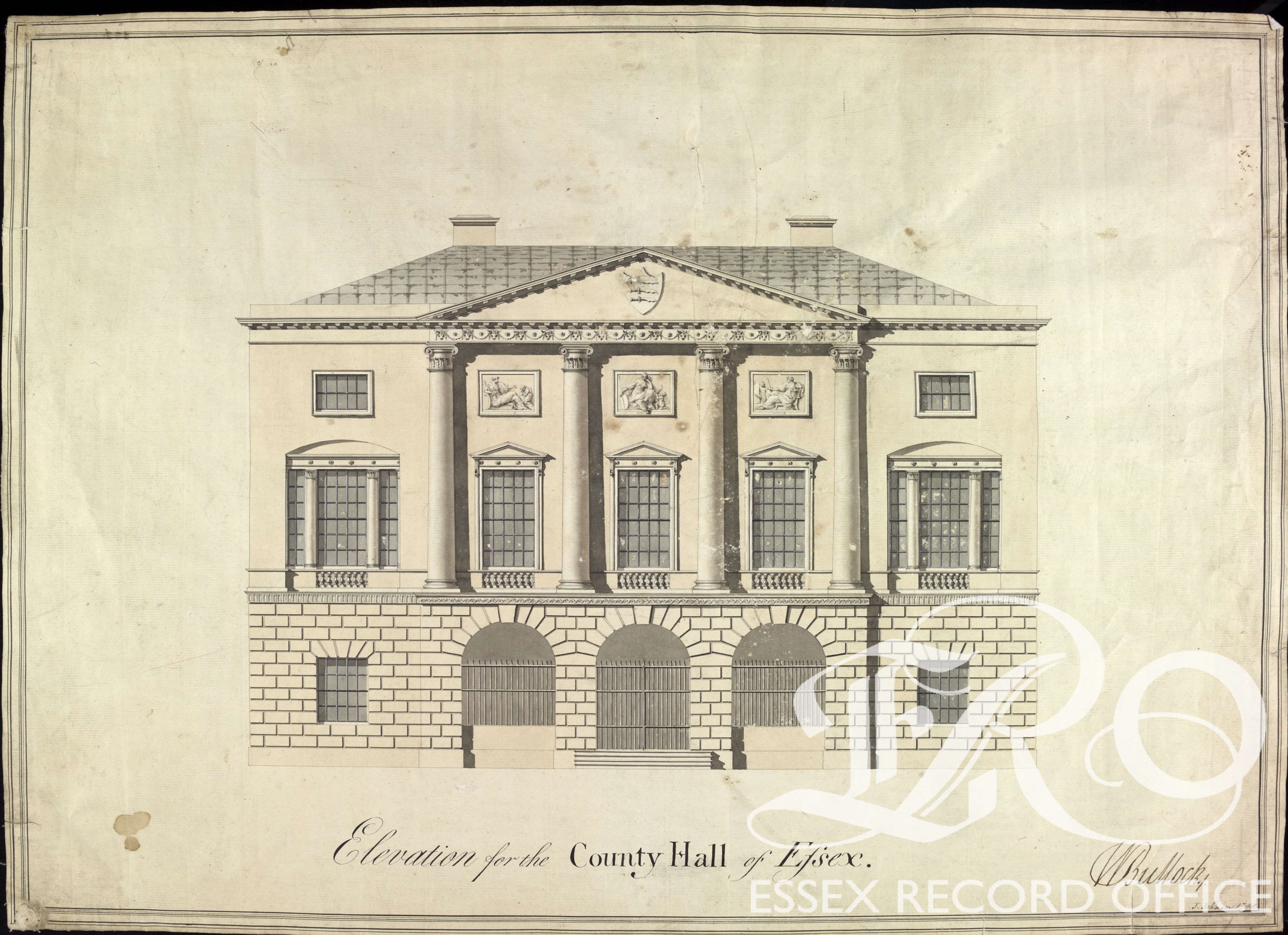

The Plans for the building of the Shire Hall in Chelmsford drawn up in 1788 (Q/AS 1/1) clearly show the Seaxes emblazoned on its neo-classical portico. These wouldn’t form a part of the final design though with this space being blank in an engraving from 1795 (I/Mb 74/1/59) shortly after the building’s completion. It now houses a clock.

[You can find about more about the history of Shire Hall on our blog – ed]

John Johnson plans for Shire Hall 1788 (Q/AS 1/1)

Engraving of Shire Hall shortly after it’s opening 1795 (I/Mb 74/1/59)

The seaxes on a red field would make numerous other appearances, among them: the Essex Equitable Insurance companies fire plate from around 1802; the Essex Local Militia ensign formed in 1809 and the Chelmsford Gazette in 1822. It appears on the cap badge of Essex Police and who remembers the single seax that appeared on the original logo for BBC Essex way back in 1986?

BBC Essex logo from 1986

The shape of the seax on Coats of Arms has led to confusion and myth. As you can see from the examples here, the shape of the Seax changes with use, the notched back of the weapon may simply be to distinguish it from a scimitar for which it is often mistaken. The notch itself has gained a myth all of its own. To many people the notch exists so that the Saxons could hook their Seax over the cap-rail of an enemy longboat to haul it closer. This sounds rather difficult to achieve, but also to justify, given that the notch doesn’t appear on any of the real world weapons categorised as Seaxes.

The Coat of Arms of Essex

Either way, the Essex Coat of Arms remains an enigmatic and iconic link to our county’s Saxon past.

I owe much of the information that I have garnered from the excellent pamphlet ‘The Coat of Arms of The County of Essex’ produced by F.W. Steer, an Archivist at Essex Record Office ,in 1949 (LIB/929.6 STE) which is well worth a read on your next visit.