We have just begun the next big expansion of digitised records available through our subscription service on Essex Archives Online, with the beginning of our project to provide digital images of our electoral registers.

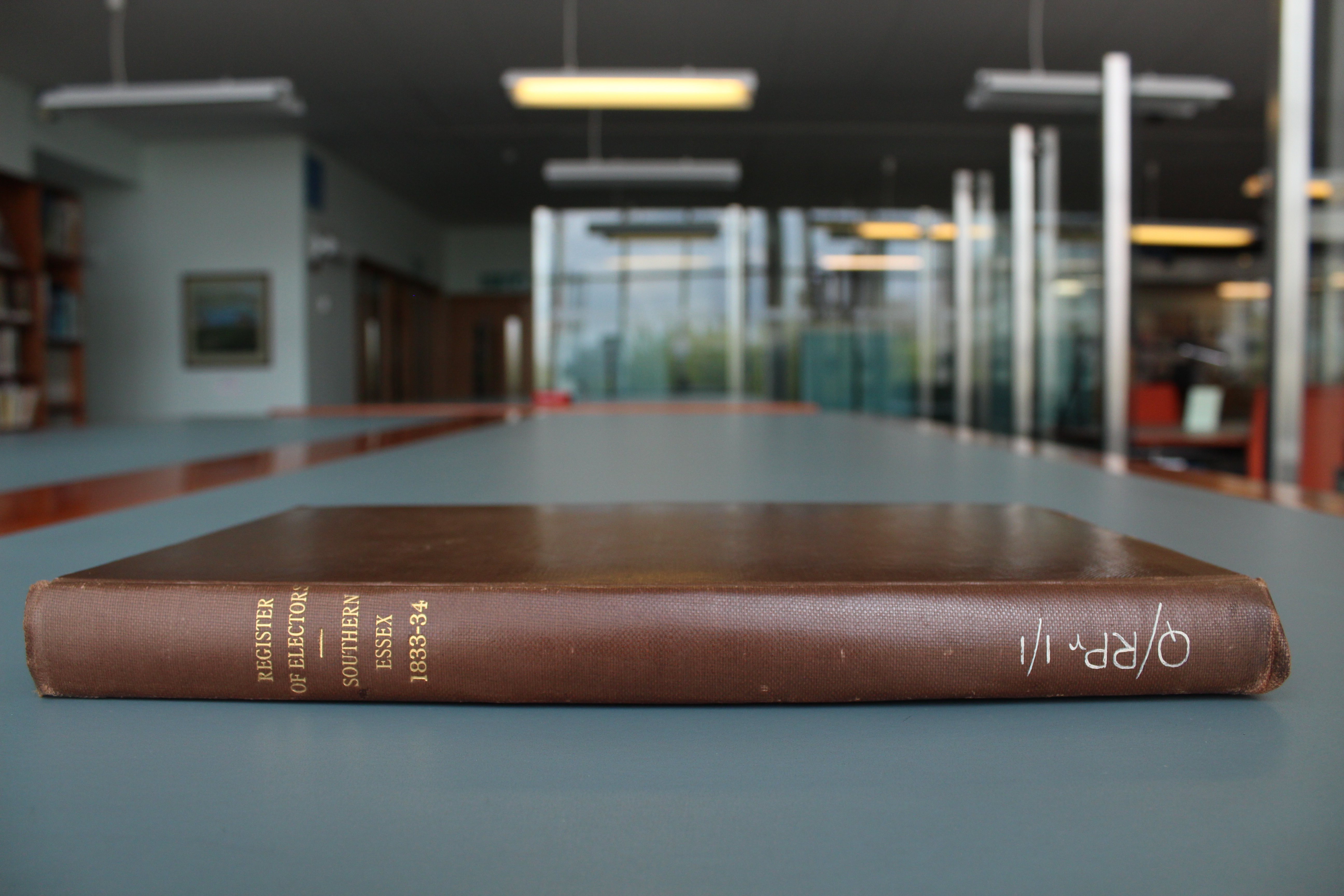

Ultimately we will be making available images of all the registers we hold from 1833-1974. The first phase of the project has just been completed, with digital images of our electoral registers from 1833-1868 now all available online. We will be releasing the images in batches, with a target completion date for the whole project of January 2018.

(There is a little caveat to this – the registers for 1918 and 1929 have been online for some time, and they will of course remain.)

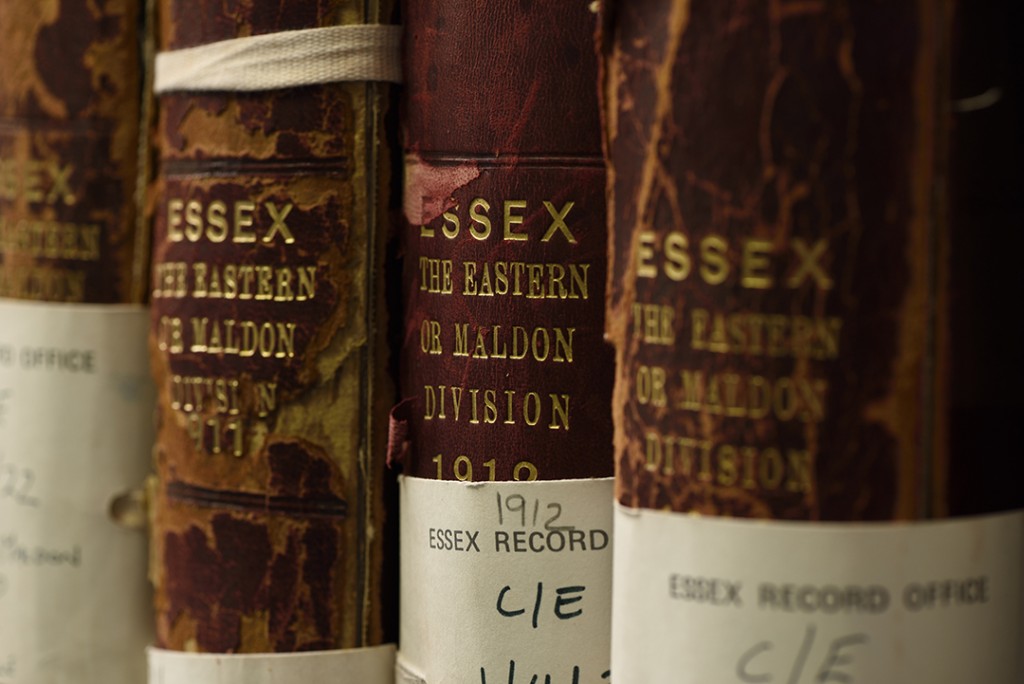

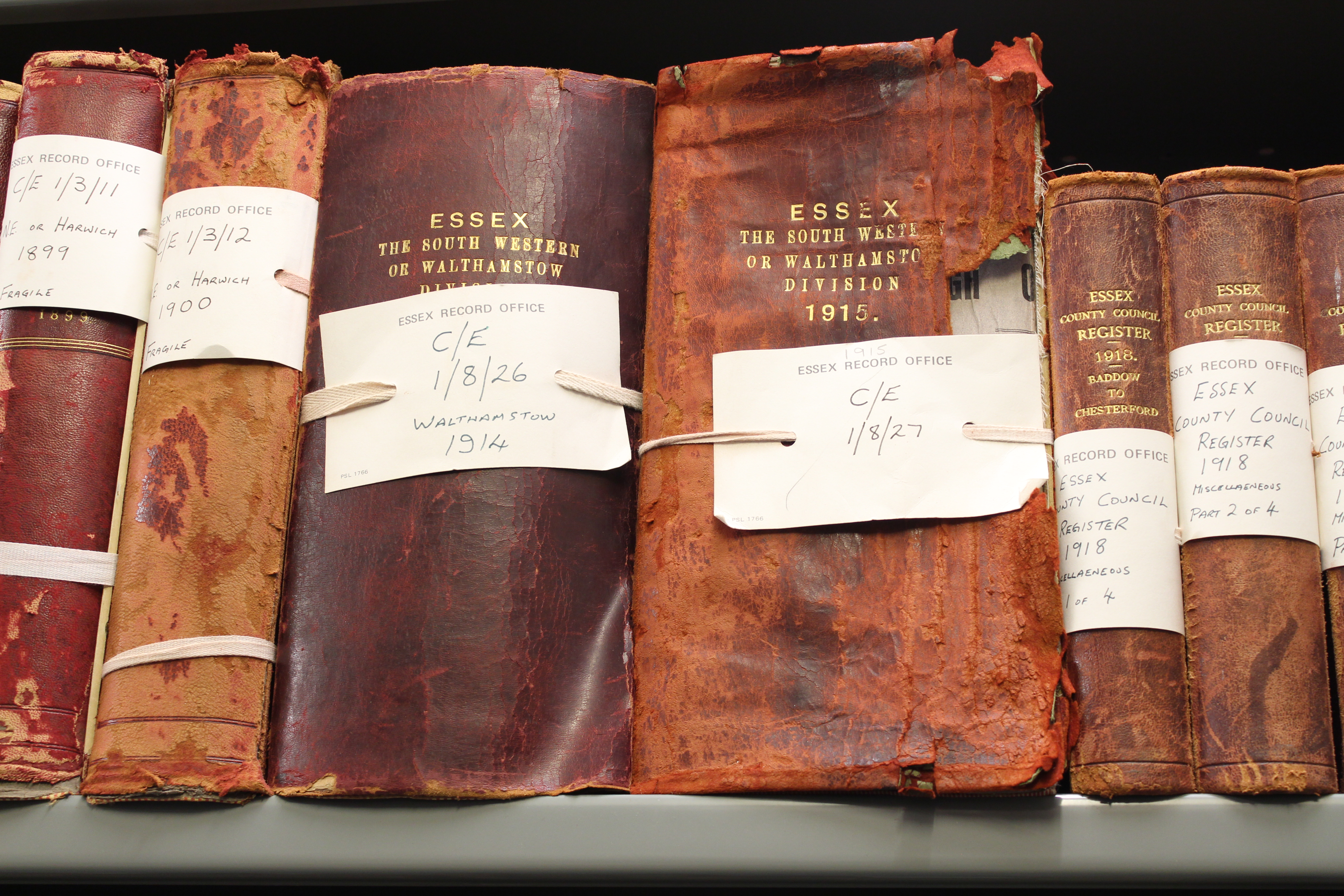

While our set of Essex electoral registers is not 100% complete, it is the best surviving set of these records, and for some registers ours is the only surviving copy. This collection of some 850 volumes provides vital evidence of Essex people’s lives and locations over almost 150 years.

As with the images of Essex parish registers and wills already available online, the images of the electoral registers can be viewed free of charge in the ERO Searchroom, or as part of our online subscription packages. Information about how to find the records and how to subscribe can be found on our subscription home page.

Why digitise electoral registers?

There are two key drivers for digitising these records: 1, to make them more widely available, and 2, to preserve the originals. Electoral registers were not designed to have a long lifespan and can be somewhat fragile. As popular records they are frequently in demand, and digitisation allows us to make the information available while protecting the original documents.

How will the records be indexed?

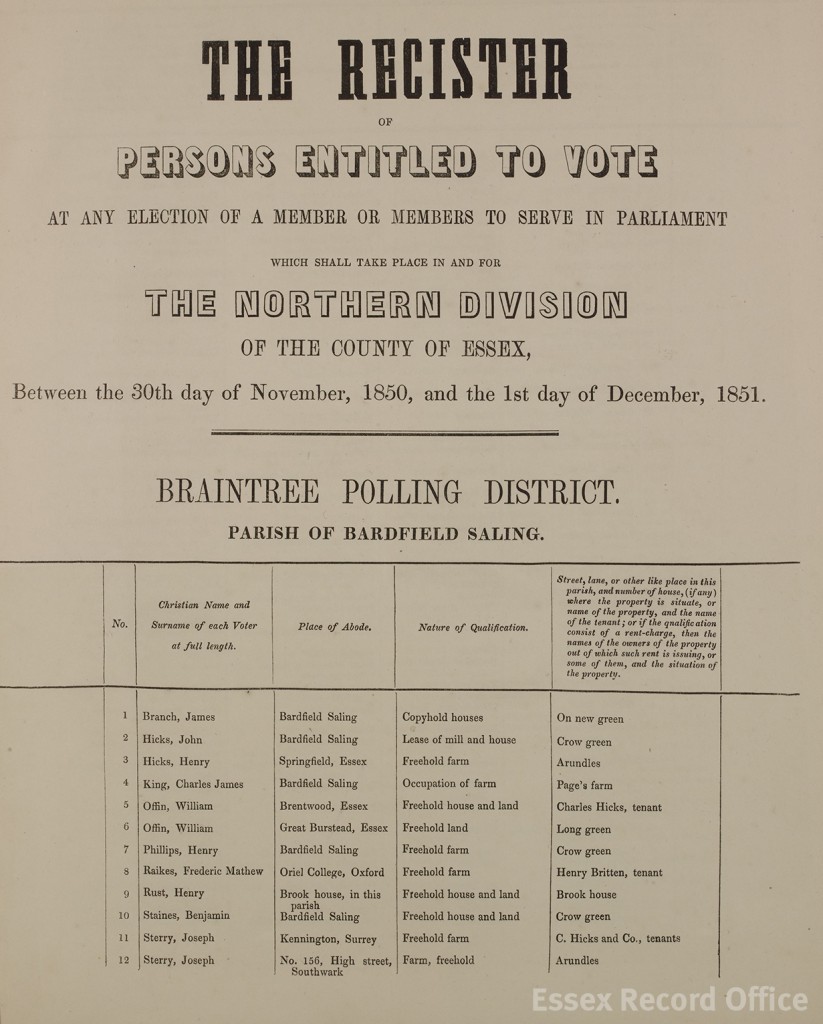

As with the parish registers already available in Essex Archives Online, we are not publishing a name index, but all of the registers in this batch are arranged alphabetically – that is, electors appear in each parish in alphabetical order of surname. This makes tracing individuals fairly easy. In addition, each register is indexed by parish or place, and they offer great opportunities not just for family historians but also for studies of local society and urban development. An annual list of the main property owners and occupiers in each place is a valuable addition to the online record, particularly where the local rate books (the ultimate source of much of this information) fail to survive.

Why do the records start in 1833?

Modern electoral registers came into being with the Great Reform Act of 1832. The Act did not hugely increase the electorate, but for the first time it required the Clerk of the Peace – the head of the county administration – to have the annual parish lists of electors’ names ‘fairly and truly copied … in a book to be by him provided’, and to give to each elector’s name ‘its proper number, beginning the numbers from the first name’. That book would be the electoral register for the following year. The Clerk was not required to print the registers, or to preserve them once the year was out, and before the mid-1840s only two survive in Essex. After that matters steadily improve, and from the early 1860s until 2001 the Record Office’s collection is fairly complete.

Who will be included in these registers?

The 1832 Reform Act expanded the electorate to some extent, but it was still limited to men aged over 21 who owned a certain amount of property. In 1851 just 11,500 county electors spoke for an Essex population of almost 370,000.

By no means all the electors for a particular parish actually lived there, or even close by, and their actual places of residence can be revealing. In 1851 the divided freehold of the King’s Head Inn at Gosfield, in the northern division of Essex, provided the qualification for 6 of the parish’s 13 electors. One lived in Chelmsford, one in Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, one in London and three in Surrey.

At Braintree, three brothers from the Buxton brewing family each held a vote in respect of Hyde Farm, the farm’s ownership being split between them. According to the register, however, Sir Edward North Buxton Bt. – who was in fact the MP for South Essex – lived in Upper Grosvenor Street, Mayfair; Charles Buxton lived near the brewery in Brick Lane, Spitalfields, Middlesex; and Thomas Fowell Buxton lived in Leytonstone (Leyton), which was at least in Essex at the time, although far away in the southern division.

At Leyton, the pattern was repeated and each of the brothers qualified once more, this time through the freehold of the Three Blackbirds inn – although Thomas Fowell Buxton had apparently forgotten that he lived in the parish and gave the Spitalfields address as his place of residence. For researchers into Victorian society, and especially the connections between land and politics, electoral registers are a mine of information.

For family historians, the names of the electors will naturally be the focus of interest, although the electors themselves are not the only people named. For example, William Wing of Bloomsbury in London had a vote in 1851 for his house in Braintree on ‘corner of square, Miss Wing, tenant’. She, of course, had no vote at all – but the naming of such voteless tenants increases the registers’ value to historians. Miss Wing is known from the 1851 census as Sarah Wing, a silversmith and watchmaker living and working in Great Square, and census users might well have wondered about a possible connection with William Wing, born in Braintree but working as a watchmaker in New Bond Street in London. Despite the gap between New Bond Street and Braintree, the electoral register evidence makes their connection almost certain, and suggests something of Sarah and William’s family arrangements. Linking the electoral registers to other sources makes the whole data set much more powerful.

How did elections take place in this period?

The process of electing MPs in the 1830s-1860s was quite different to today. There were two different kinds of constituencies – counties and boroughs. The theory was that county MPs would represent landholding interests, and borough MPs the interests of the mercantile and trading classes. Before 1832 Essex sent 8 MPs to Parliament – 2 from the county seat of Chelmsford, and 2 each from the ancient boroughs of Colchester, Maldon and Harwich.

Before 1832 there was enormous variety in the size of constituencies and in voting qualifications. Polling could last up to 40 days, and there was no secret ballot. The whole system was liable to corruption and domination by local elites.

The 1832 Reform Act went some way towards resolving some of these issues. Most rotten boroughs (boroughs with tiny electorates controlled by a wealthy patron) were abolished, and seats were redistributed to growing industrial towns. Polling was limited to two days, and the qualifications for the franchise were standardised.

Essex gained two more MPs as part of the changes as the county constituency was split into two divisions, north and south, each returning two MPs, in addition to the two each still returned from the three ancient boroughs.

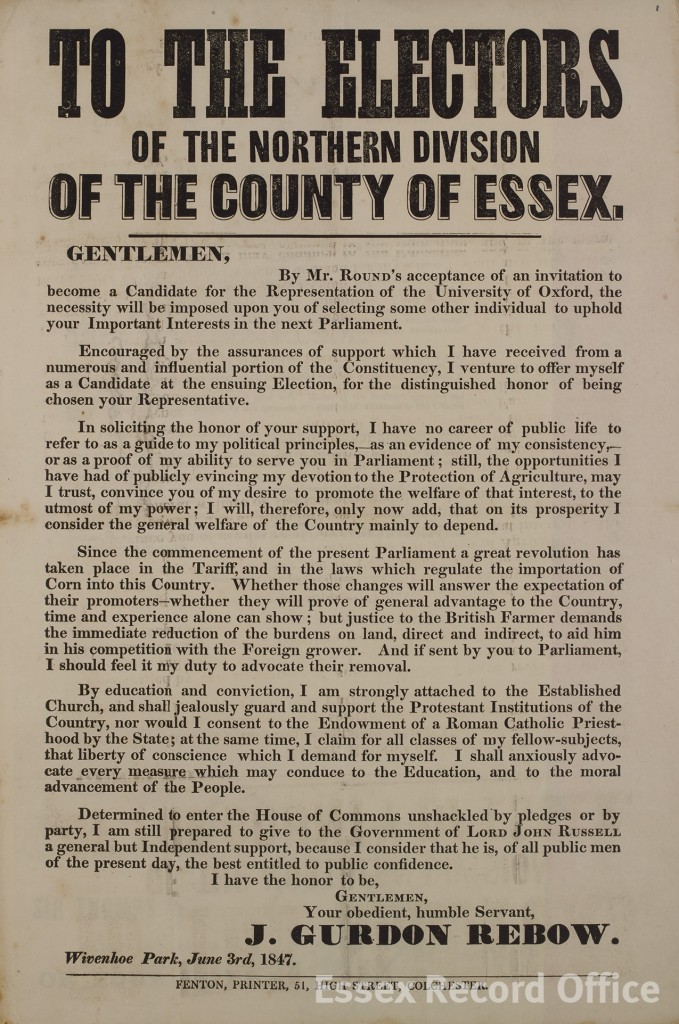

Flyer by John Gurdon Rebow of Wivenhoe Park, who stood as an independent candidate for North Essex in the 1847 general election. The policies he outlines here include the protection of agriculture, and of the Church of England and individual liberty. He was not successful on this occasion, but was MP for Colchester between 1857 and 1859, and again from 1865 until his death in 1870. (T/P 68/38/9)

Looking to the future…

Further reforms were, of course, to come, and successive electoral registers include more and more people, until finally all men and women over 21 were granted the vote in 1928. We will continue to post updates on the blog as the electoral register project progresses, and we hope you enjoy exploring the new images.