Sound Archivist Sarah-Joy Maddeaux reflects on how our soundscapes have or haven’t changed during the current lockdown.

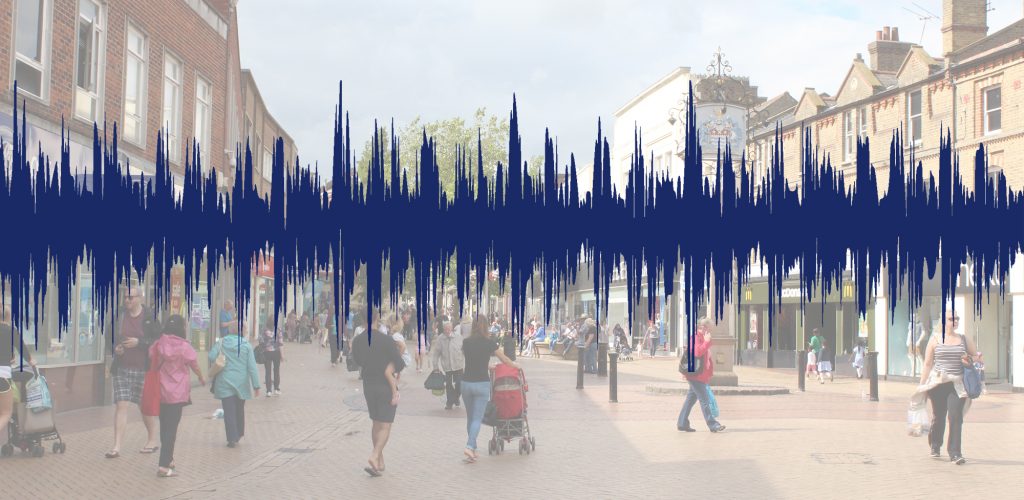

Numerous comments have been made about how quiet it is during lockdown – that there is less air traffic, less road traffic, less general hub-bub. Eminent wildlife recordist Chris Watson has spoken of the ‘unique opportunity’ to listen to ‘astonishing’ soundscapes we can hear in our own back gardens. Audio ecologists such as Barry Truax and Hildegard Westerkamp have described the way our ears can now tune into sounds from a much greater distance, as overall noise levels decrease – a ‘depth perception’ that we wouldn’t normally perceive.

It is true that the number of flights have drastically decreased – you can check what’s overhead right at this moment with a flight tracker website or a surprisingly interesting Twitter feed. As you will see, it is misleading to say that air traffic has stopped – people are flying home, sometimes in special planes chartered to retrieve them. Medical supplies are frantically being sent all over the globe. Can someone on a normal flight path tell us their impressions of the impact? Because there are fewer aeroplanes, does that make us notice them more?

Some noises are ‘normal’, but the current context heightens our awareness of them. Sirens screaming are a frequent occurrence at any time, and, particularly if you live in a city, you learn to filter them out. But now when we hear a siren, do we assign more significance to it? Does it make us feel worried, afraid, sad – or thankful for the emergency services?

Is there more birdsong? Or are we just noticing it more? If there is less other environmental noise, it does not make sense that the birds are singing louder – they have less to compete with to make themselves heard. Maybe the sounds are more audible, because there are fewer other distractions, and we pay more attention to them because we are at home more, out in the garden more. Or perhaps this is just our perception because lockdown coincided with spring, when birds typically become more audible.

I do not often work from home, so I cannot judge whether the amount of human activity I can hear has changed. Can I hear more conversations as people run into neighbours on the way to the shops because they are speaking to each other from further away, and therefore more loudly? Or are people more likely to chat because we all need to reach out for human contact? Can I hear more conversation as people are queuing outside shops, instead of breezing in and out?

Then there are new sounds. Communal dancing in the street. Clapping and clanging pots for frontline workers each Thursday evening.

What is really going on? What are the real pandemic soundscapes? Let’s put these sweeping statements to the test.

First, open a window. Second, set an alarm to go off in five minutes. Now, find somewhere comfortable to sit. Open your ears. Close your eyes.

What did you hear? This is what I heard from my lockdown workspace:

- Two constant background noises: a ticking clock on the bookcase behind me, and the high-pitched chirping of birds, probably in the trees nearby.

- Cars and possibly a larger vehicle driving round my block of flats, with associated noises like a car door shutting, a car engine starting up.

- A runner’s footsteps rhythmically slapping the pavement.

- Birds rustling tree branches as they fly off or land.

- A child’s voice, distantly heard.

- Pigeons cooing.

- A sea gull squawking.

- The flapping wings of a small bird fluttering near my window.

- A lawnmower.

- The beeping of a reversing lorry, in the distance.

- Frequently, the double beep noise that’s made every time someone opens the door to the nearby convenience store.

What did you hear? How did it make you feel? It is ok if your soundscape does not have the calming, peaceful effect that is so commonly described. It is understandable to feel anxious by sounds you hear. As always in history, the individual experiences of and responses to events are complex.

The absence of sounds is not always welcome. The comforting noise of cricket bat against ball on the village green. The happy chatter from beer gardens on a warm Friday evening. The automated voice telling you that you have, at last, reached your local station on your daily commute home. Or maybe you miss some of the sounds of your workplace. For me, it’s the satisfying clunk of a cassette tape being loaded into a player – it goes without saying that I miss hearing the collections themselves.

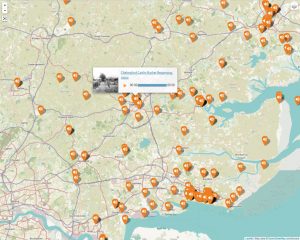

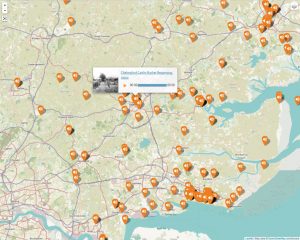

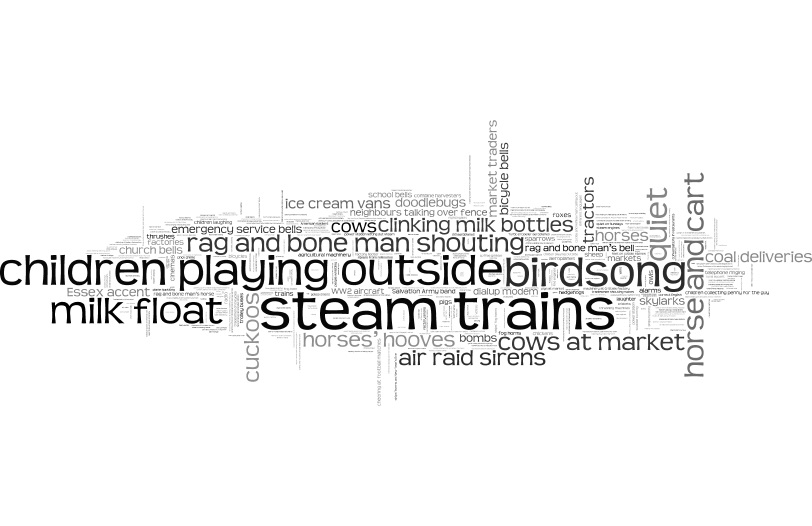

Whatever you experienced, we want to hear your #StayHomeSounds. Safely from your home or garden, record what your lockdown sounds like. Then send it to us at explore.essex@essex.gov.uk. It would help if you can provide information about where and when it was recorded, plus a little about why you recorded it and your reactions to those noises. We are compiling sounds on our Essex Sounds map, and we may use them for other resources. Please contact us if you want more technical details about how to make your recording.

If you want to hear what the pandemic sounds like in far-flung lands, there are a number of global sound maps you can dip into, such as at Radio Aporee and Sounds of Cities. How different is the situation in India, or Marseilles?

Or if you want some escapism, tune into BBC Essex each morning at around 9:55 a.m. for a daily soundscape of things we can’t currently enjoy, or explore our Essex Sounds map of past and present sounds of Essex.

We’ll leave you with this clip of the dawn chorus recorded on 7 May 2017, on the outskirts of Chelmsford – how does it compare with the dawn chorus you might have heard today, on #InternationalDawnChorusDay?