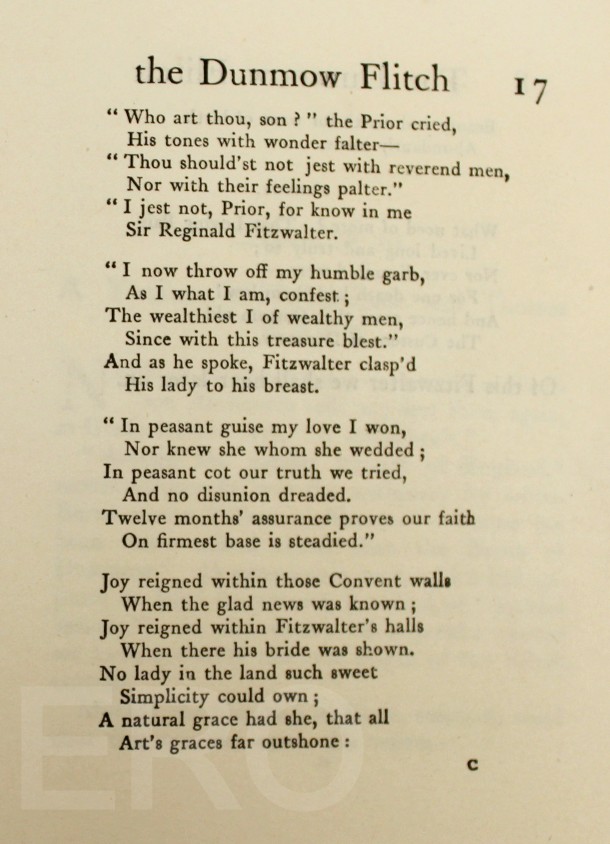

The tradition of the Dunmow Flitch Trials is commonly dated back to 1104 when a local Lord and Lady supposedly visited the Augustinian Priory of Little Dunmow disguised as paupers. They asked the prior if he would bless their marriage which had taken place a year and a day previously. Impressed by their apparent devotion to each other, the prior responded by presenting them with a flitch of bacon (which the Priory cook happened to have been carrying past at the time).

At this point the Lord, Reginald Fitzwalter, threw off his present garb and thanked the prior for his willingness to believe in their love. He then gifted some of his land to the Priory on the condition that a flitch of bacon would be given to any couple that could come to the Priory and prove their continued devotion to each other a year and a day after their marriage.

As charming as it is, this story has obviously been the cause of much doubt over the years – but what can’t be doubted is the fame that the Dunmow Flitch Trials had gained by the 14th century. Both William Langland and Geoffrey Chaucer refer to the trials in their books, and they both used language which assumed readers were already familiar with the tradition. However, the first official record does not appear until 1445 when Mr and Mrs Richard Wright were awarded their flitch of bacon.

The tradition lapsed over the years and, in 1832, Josiah Vine’s request for a trial was refused on the grounds that it was ‘an idle custom bringing people of indifferent character into the neighbourhood’.

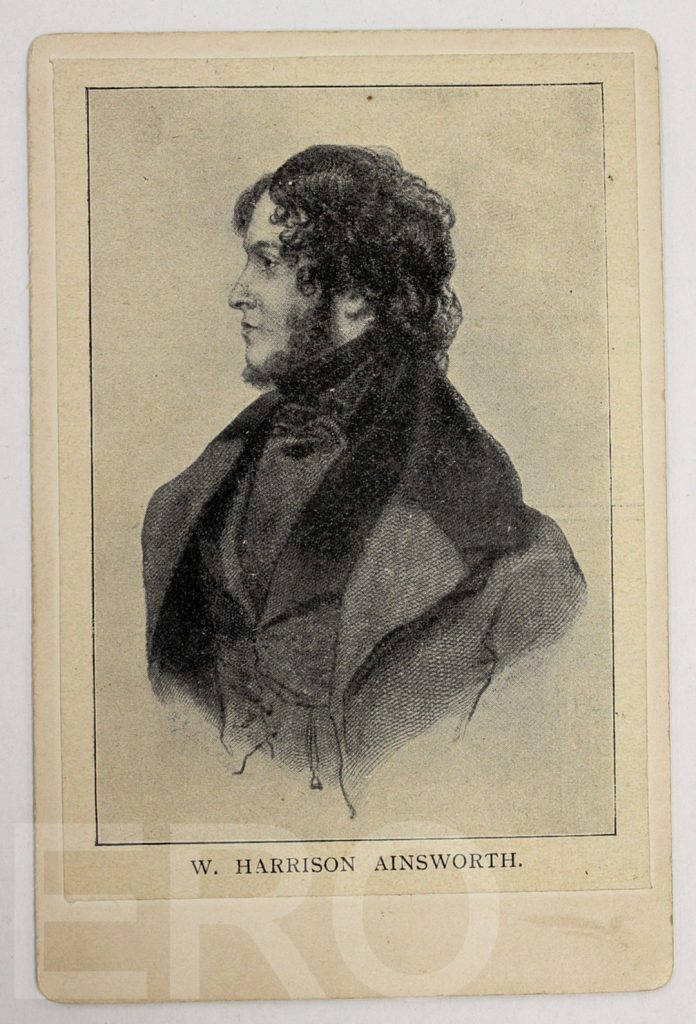

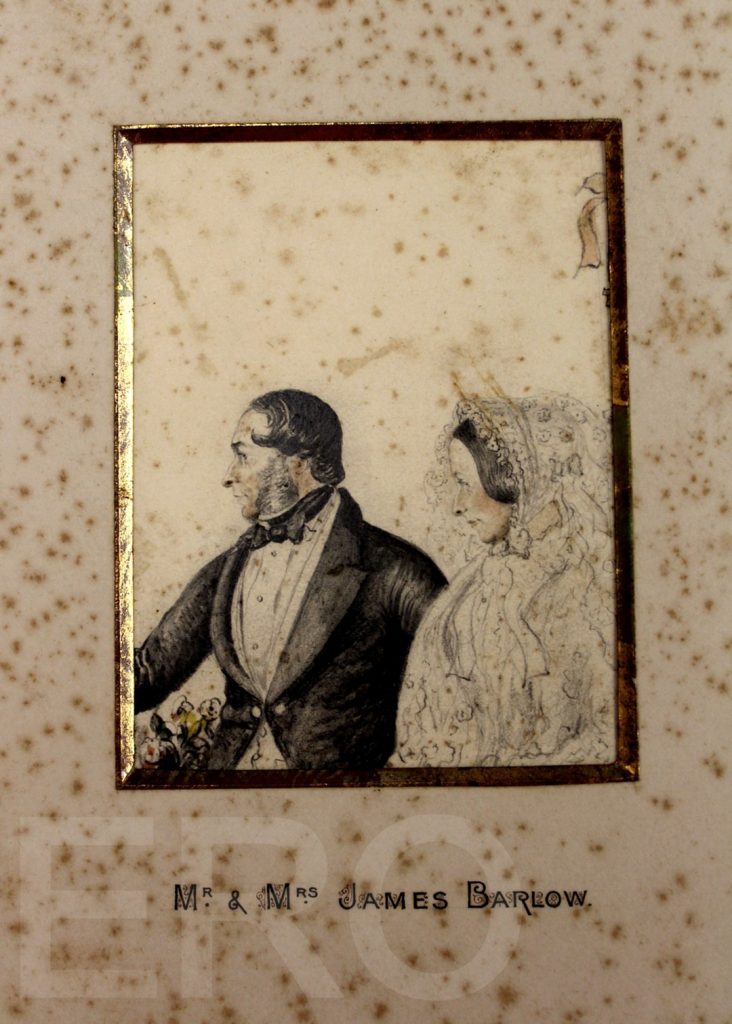

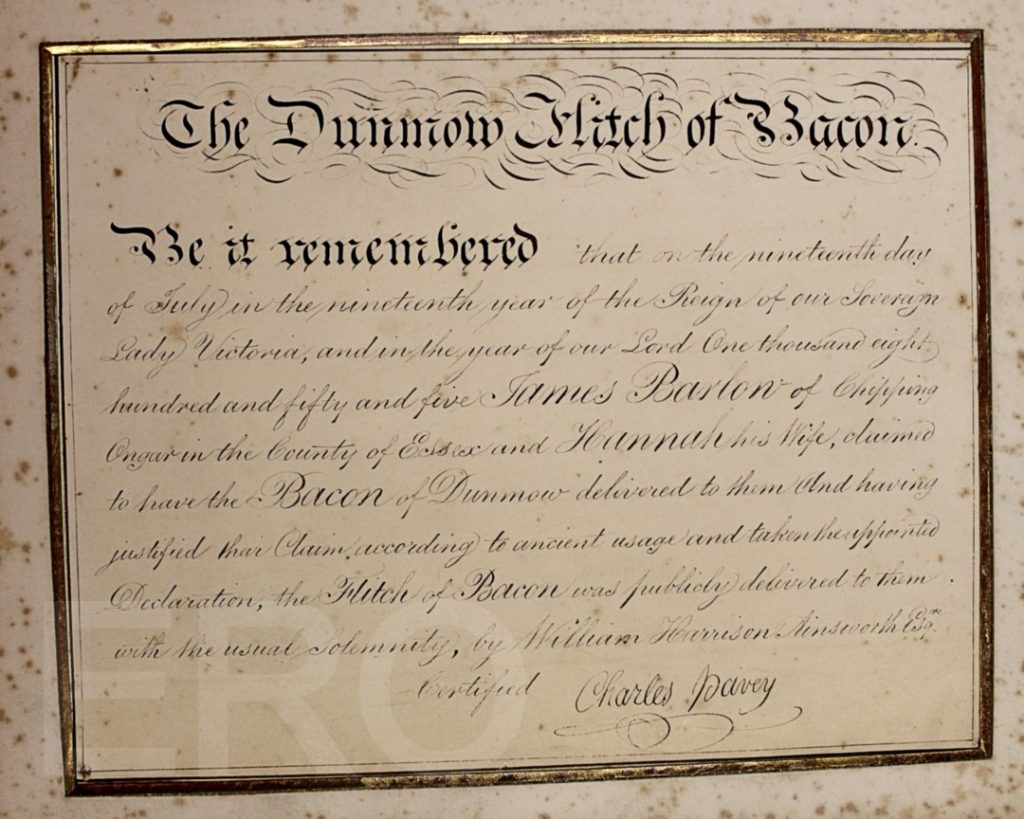

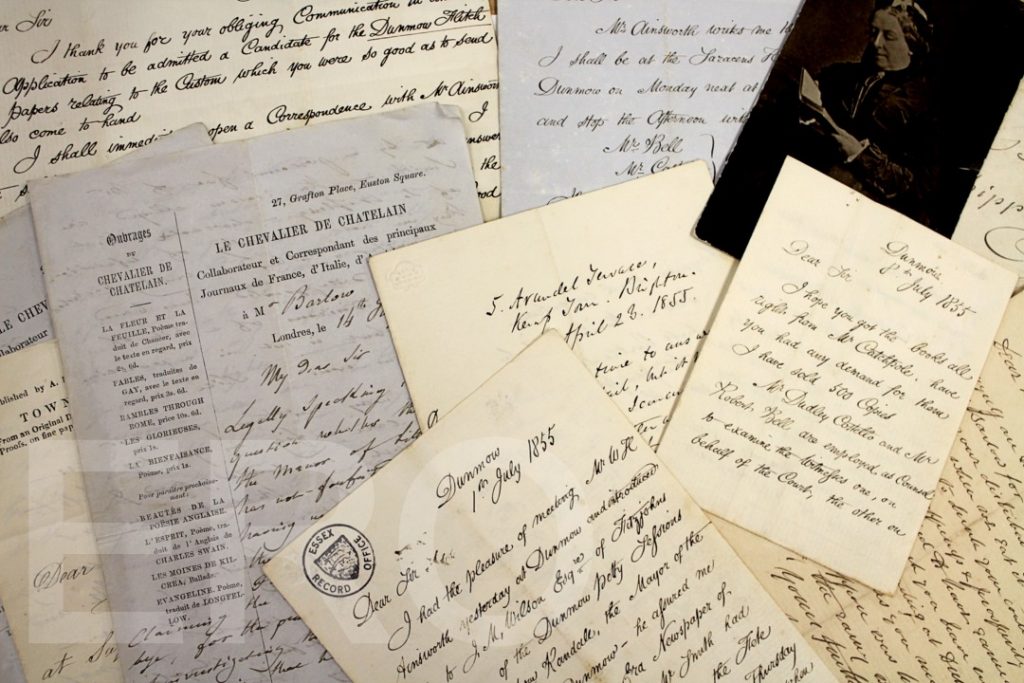

Fortunately, the novelist William Harrison Ainsworth sought to revive the tradition in 1854 with his book ‘The Custom of Dunmow’ and in the following year he personally presented the flitch to two couples. One was a French gentleman and his English wife: the Chevalier and Madame De Chatelain. The other was a local couple from Chipping Ongar: James Barlow, a builder, and his wife Hannah.

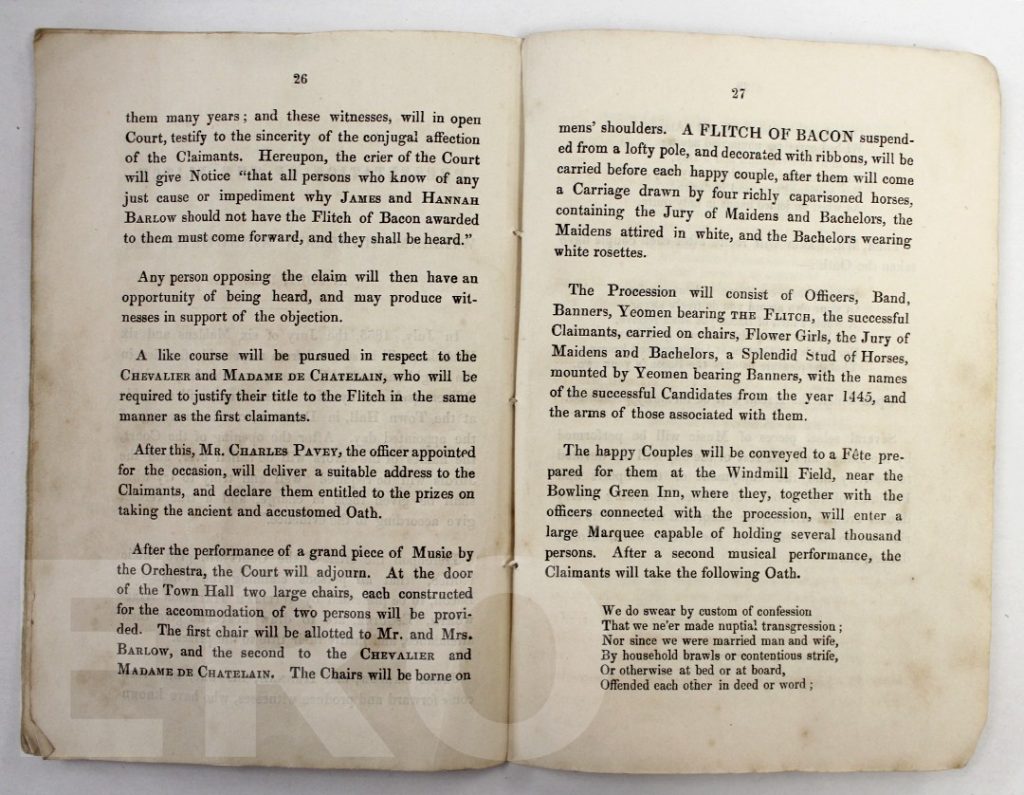

During the trials, both couples were required to prove their enduring love before a jury of six maidens and six bachelors. There was also an opposing council which represented the donors of the flitch of bacon and challenged the evidence with the aim to dissuade the jurors from awarding the flitch to the couple. Successful couples were then seated in the Flitch Chair and carried in a parade, at the end of which they were required to take this oath:

‘We do swear by custom of confession

That we ne’er made nuptial transgression;

Nor since we were married man and wife,

By household brawls or contentious strife,

Or otherwise at bed or at board,

Offended each other in deed or word;

Or since the parish clerk said “Amen,”

Wished ourselves unmarried again;

Or in a twelvemonth and a day,

Repented not in thought or in any way,

But continued true and in desire

As when we joined hands in the holy quire.’

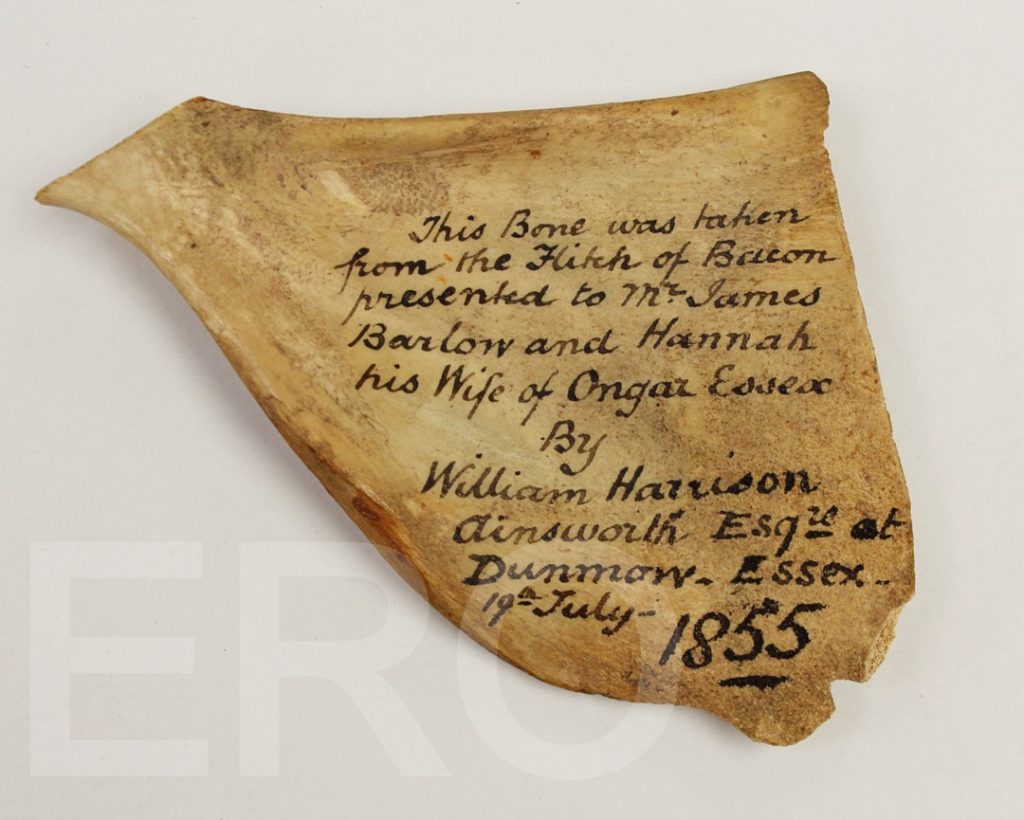

After the Dunmow Flitch Trial, an album was compiled to commemorate the occasion. It consists of the following framed items: a painting of James Barlow, a sketch of James and Hannah Barlow, a commemorative certificate, and a picture of the Dunmow Town Hall. At the back of this album is a disguised compartment holding letters about the planning of the event, a programme from the day itself, a pamphlet about the history of the Dunmow Flitch and (perhaps most remarkably) the shoulder bone from the Barlow’s flitch of bacon!