Archivist Lawrence Barker tells us about his choice for Document of the Month: a newly accessioned Church Book from Colchester dating from 1796-1816 (D/NC 42/1/1A).

A year of ‘war and confusions’: this is how the Reverend Joseph Herrick (1794-1865) described 1815-16 at the Church of Christ in Colchester.

Revd. Joseph Herrick, who was minister of Stockwell Congregational Church in Colchester for over 50 years, from 1814 until his death in 1865 (I/Pb 8/16/2)

Herrick had been elected as minister of the congregation in 1814. At the time, the Church of Christ met in a building on Bucklersbury Lane, which is now St Helen’s Lane. (The congregation was later to build what would become Stockwell Congregational Chapel.)

Several new (to us) documents relating to Herrick’s early years at the church were recently deposited at ERO. The two most significant items are a commonplace book, a kind of journal kept by Herrick himself recording his activities as a preacher from 1813 to 1819, and a church book, which is a record of church activities and members from 1796-1816, which Herrick must have kept in his personal possession. After his death, it must have passed down through his descendants and has thus survived. It is an important record relating to the early history of the Congregational Church in Colchester which has remained hidden for 200 years.

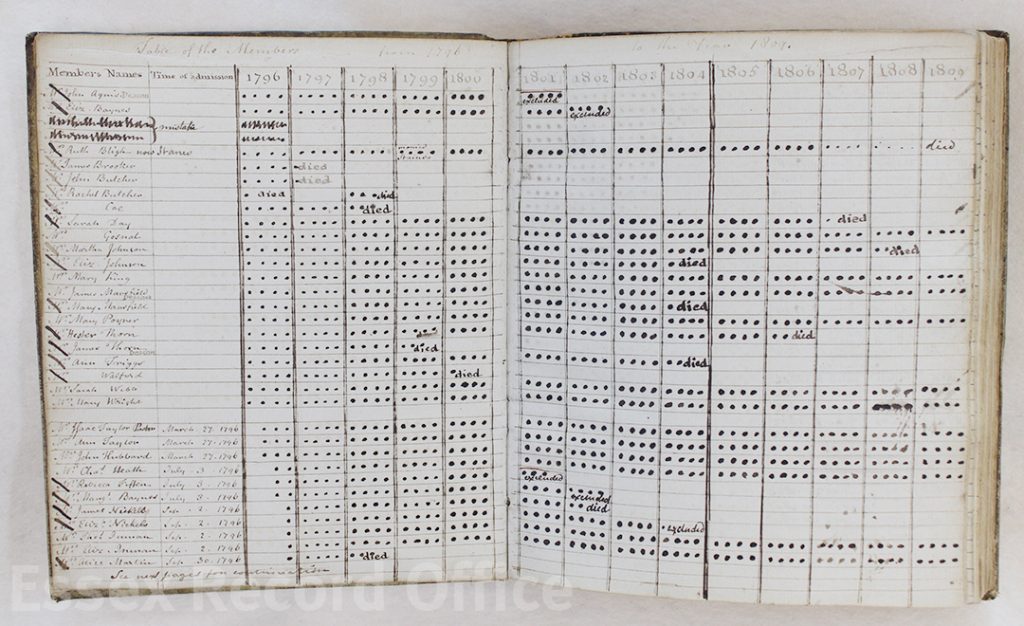

One function of the church book was to record the names of members of the church, noting when they joined and when they either left, died or were ‘excluded’ during disagreements (D/NC 42/1/1A)

The book begins by recording the ministries of Herrick’s predecessors Isaac Taylor and Joseph Drake. Drake’s ministry was plagued by a quarrel over a man named John Church, who had been invited to preach in the church by some members of the congregation. The majority of the members, however, disapproved of Church’s views: he was an antinomian, that is, he held the view that salvation could be achieved by faith alone, and people were not compelled to follow moral laws by any external influence.[1] Such a row followed that Drake resigned, having been in post less than a year. From March 1812 and throughout 1813 the church was without an appointed minister, and nothing was entered into the church book during this time. At the time of Herrick’s official election in April 1814, the book records that:

This Church was thrown into a great deal of confusion in the year 1813 by a Mr Church, an Antinomian Preacher, of very vile character, being forced into the pulpit contrary to the wish of the generality of the people.

In December 1813, Herrick came down from London and preached his first sermon at the Church of Christ on Christmas Day. After labouring amongst the church for 3 months ‘with a view to a settlement if things were mutually agreeable’, an invitation dated 16 January 1814 was sent to Herrick signed by the Deacon, James Mansfield Senior, and other members of the church.

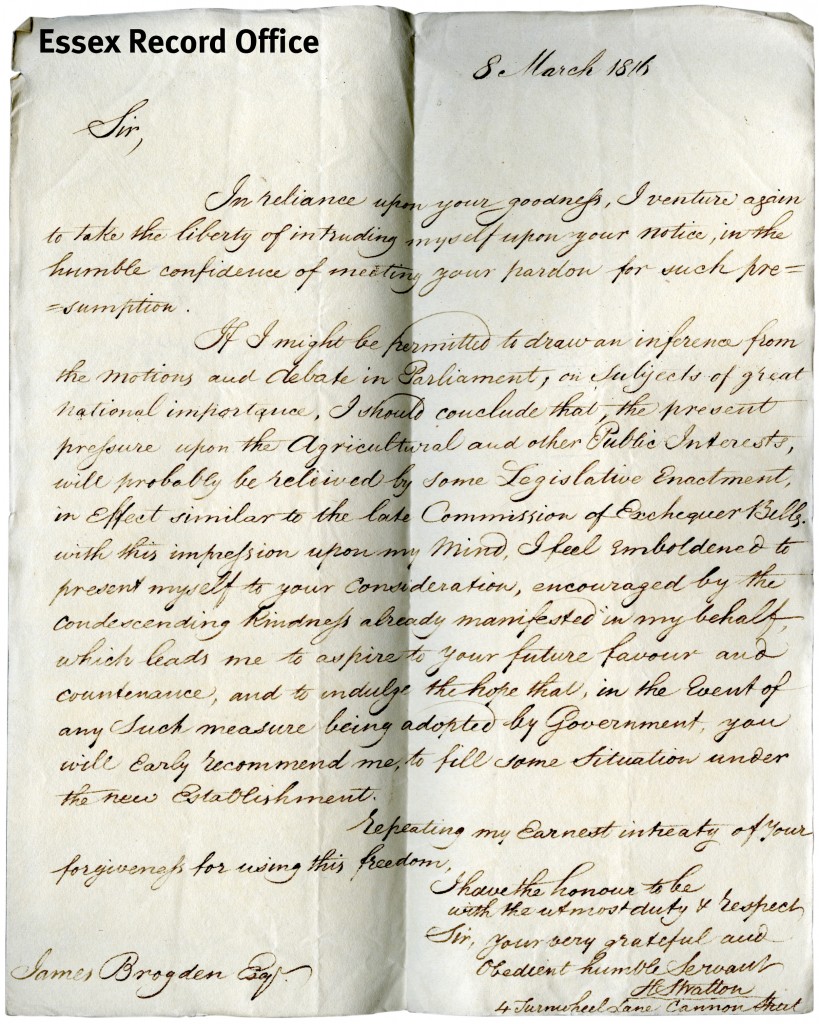

Yet Herrick’s ministry does not seem to have restored harmony to the church, in the main because a conflict arose between him and the very Deacon responsible for his ordination, James Mansfield. Things came to a head in June 1815. Mansfield concocted a letter of dismissal (D/NC 42/6/6) dated 6 June to send to Herrick stating that ‘from and after the twenty fourth Day of June instant your services as Preacher at such Meetinghouse will be dispensed with. And that from and after such time we shall Consider you entitled to no payment of a Minister for the performance of Divine Service in such Meetinghouse’. The letter is signed by Mansfield and others of his cronies (some of which are thought to have been invented).

In the short term, Herrick seems not to have been affected by this:

June 14 1815

Our 15 Church meeting was held. – this was a special meeting called to consider the conduct of James Mansfield Senr Deacon, Mary Tillet and Mary Wright, when it was unanimously agreed that their conduct was highly inconsistent; and such as we could by no means tolerate. Mr M had abused his pastor, insulted the members, destroyed the harmony of the church, kept back part of the subscriptions etc etc – and the others had been concerned with him, and supported him in all his improper practices. All suspended.

In August, an intermediary tried to help resolve the situation:

August 14, 1815

Our 16 Church meeting was held. This was a special meeting, to hear the report of the Rev W B Crathern, who had been requested to attempt an adjustment of the differences between the church and Mr Mansfield Senior etc. His interference had been, he stated, without effect, entirely owing to the obstinacy of Mr Mansfield. He advised the church not to consider him as suspended, but to try him a few months longer and if no alteration appeared, then, to cut him off. Agreed to etc. Joseph Herrick.

In September, having accepted (presumably) James Nash as his new Deacon, Herrick reported that Mansfield ‘refused to deliver to Mr James Nash, Deacon the sacramental cups which are the property of the church; awful sacrilege! We, however, bought one which we administered the Lord’s supper on the 10th’.

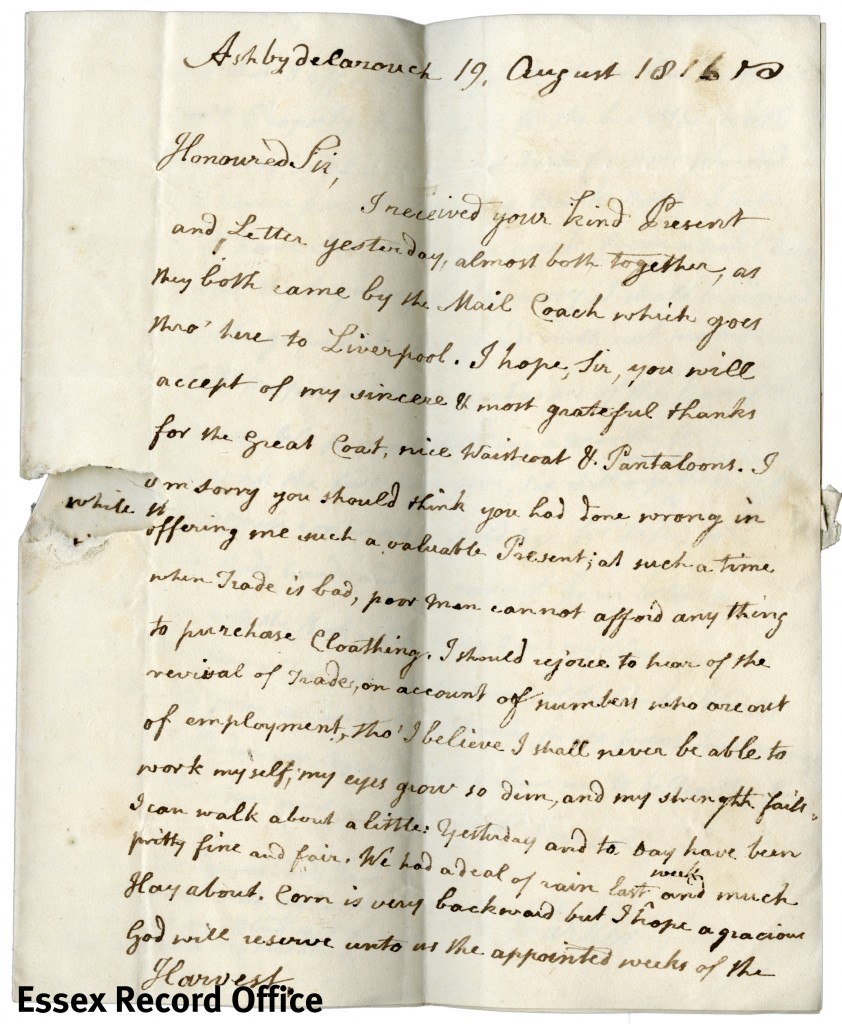

By February 1814, desperation seems to have begun to set in:

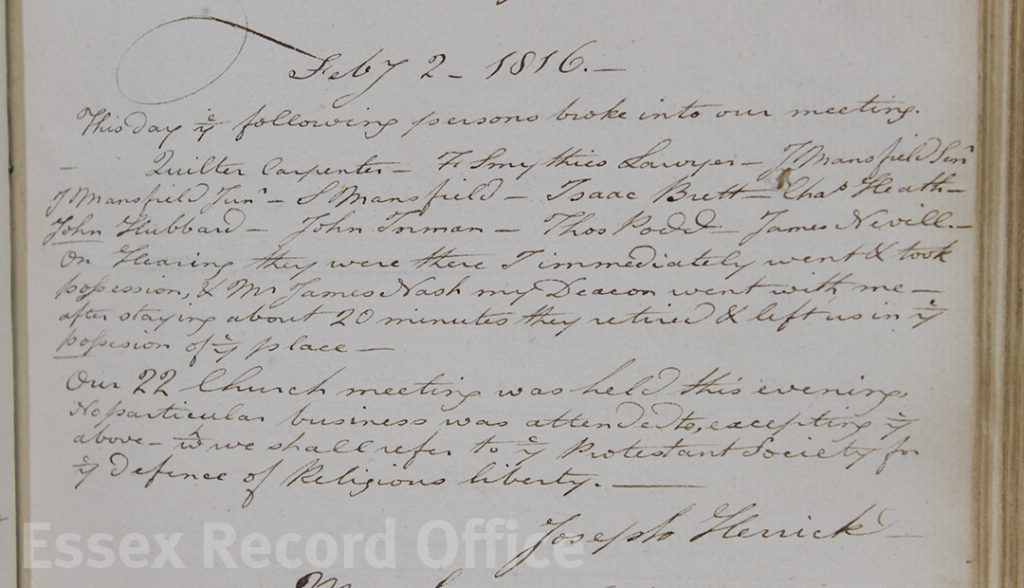

February 2, 1816

This day the following persons broke into our meeting. –

Quilter, carpenter, F Smythies, lawyer, J Mansfield Senior, J Mansfield Junior, S Mansfield, Isaac Brett, Chas Heath, John Hubbard, John Inman, Thos Podd, James Nevill. On hearing they were there I immediately went and took possession, and James Nash my Deacon went with me – after staying about 20 minutes they retired and left us in the possession of the place.

Our 22 Church meeting was held this evening, no particular business was attended to, excepting the above, which we shall refer to the Protestant Society for the defence of Religious liberty.

Joseph Herrick

Entry in the church book from 2 February 1816 when the church meeting was disrupted by several members of the congregation (D/NC 42/1/1A)

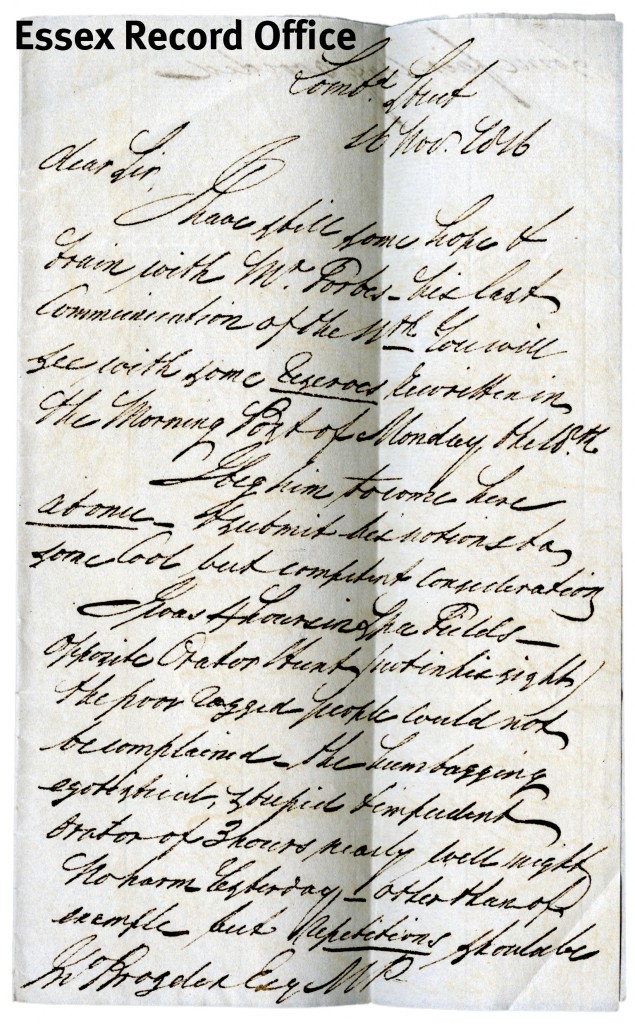

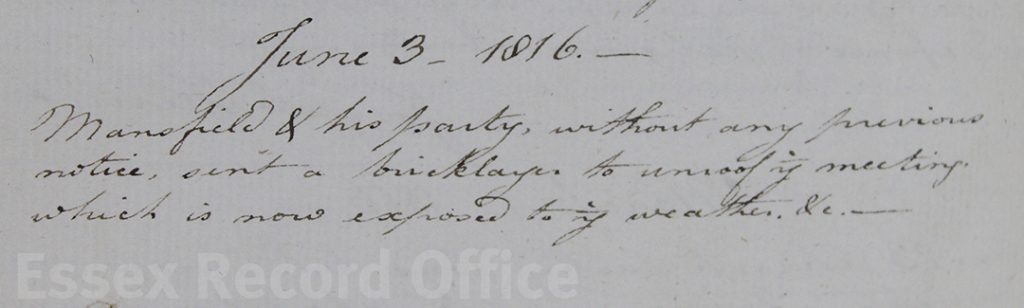

Eventually, so determined it seems was Mansfield to dispense with Herrick as Pastor that he went to the extraordinary expedient of organising the de-roofing the chapel so that it could no longer be used as a meeting place, a development laconically reported by Herrick as the last entry in the church book:

June 3 – 1816 –

Mansfield and his party, without any previous notice, sent a bricklayer to unroof the meeting which is now exposed to the weather etc.

Entry from the church book for 2 June 1816, when the roof was removed from the church by a disgruntled member of the congregation (D/NC 42/1/1A)

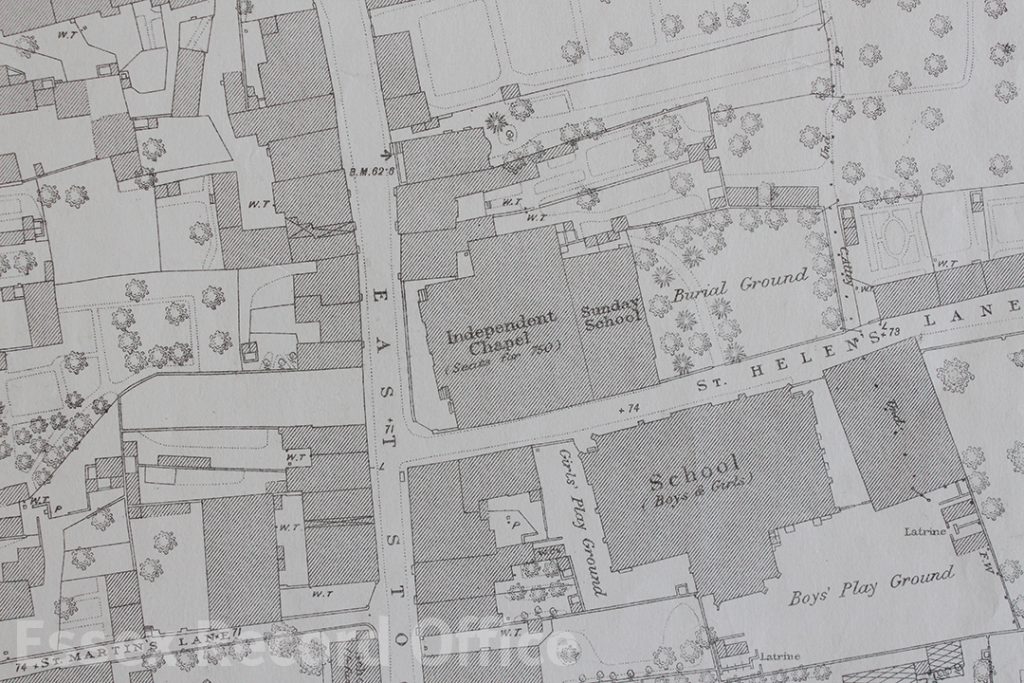

But that wasn’t going stop Herrick pursuing his mission. He simply built a new chapel 50 yards further along St Helen’s Lane, on the corner with East Stockwell Street, which was to eventually become Stockwell Congregational Church. This new chapel was enlarged in 1824 and 1836 to accommodate a growing congregation.

This 1870s map of Colchester shows that by this time the chapel had seating for 750 people and an attached Sunday School (Ordnance Survey first edition map 27.12.3, 120”: 1 mile)

Herrick remained its minister until his death in 1865; he is buried in Colchester Cemetery, where a large obelisk dedicated to his memory stands. On his death it was estimated that he had conducted over 10,900 services in his 51 year career in Colchester. While he was never universally approved of, he clearly had a large band of very dedicated followers. An obituary for him in the Essex Standard of 8 February 1865 describes a man ‘Firm in purpose’, with ‘gravity and sobriety’, who was deeply knowledgeable not only on Christian theology but on a whole range of other subjects as well, who practiced what he preached and unaffectedly sympathised with ‘those in sorrow’. For his congregation, his loss after so many years must have been felt deeply indeed.

The church book will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout June 2018.

[1] Antinomianism is one of many debates within Christianity. The word itself literally means rejection of laws (from the Greek ‘anti’ meaning against, and ‘nomos’ meaning laws). In Christianity, antinomianism is part of the debate about whether salvation is achieved through faith in God alone, or through good works. An Antinomian in Christianity is someone who takes the view that salvation is achieved by faith and divine grace, and those who are saved in this way are not bound to follow the laws set out in the Bible. However, this is not to say that someone with antinomian views believes that it is acceptable to act immorally, rather, that the motivation for following moral laws should flow from belief rather than external compulsion. In this view, good works are considered to be the results of faith, but good works above and beyond what is required through faith were viewed as signs of arrogance and impiety.