In the run up to ERO’s trip to Boston, we take a look at the life of Thomas Hooker, Chelmsford’s town lecturer who went on to become one of America’s founding fathers.

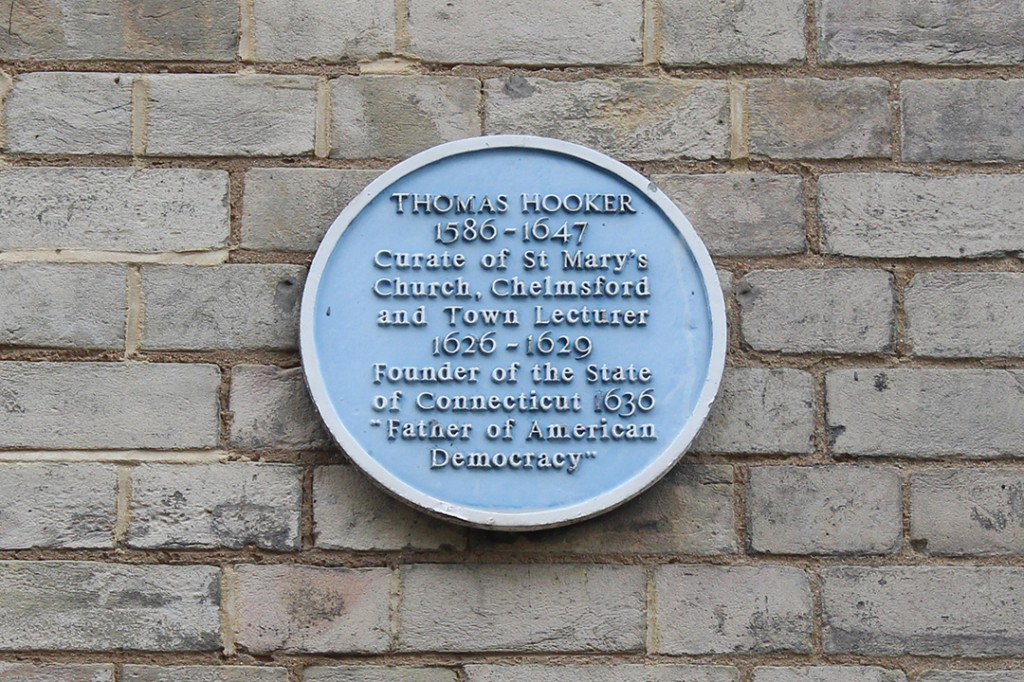

Thomas Hooker (1586-1647) spent the years c.1625-1631 in Chelmsford as the town’s lecturer, drawing large crowds to his sermons. In 1633, along with his wife and children, he made the perilous voyage from England to New England. He went on to become one of the most important men in the new world and is well known in America today, as a co-founder of the state of Connecticut, and the ‘Father of American democracy’, yet he is little known in the country of his birth.

Hooker was born in Leicestershire and studied at Cambridge, as part of a circle including several future Puritans. Puritans were extreme Protestants who were unhappy with what they saw as Catholic elements in the structure and style of worship in the Church of England.

Chelmsford

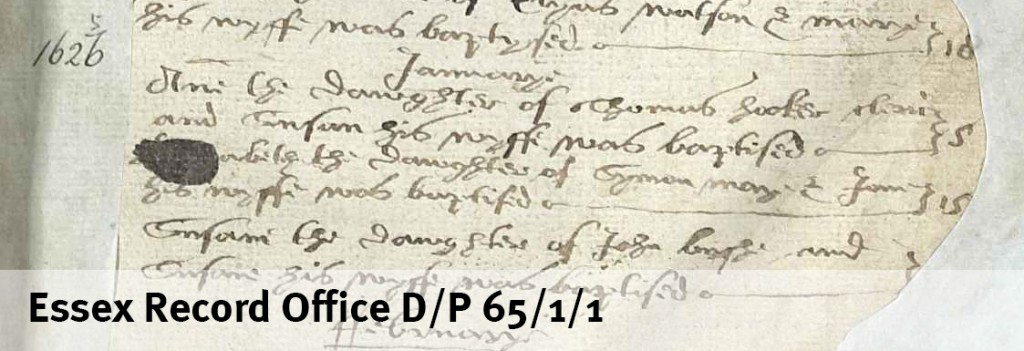

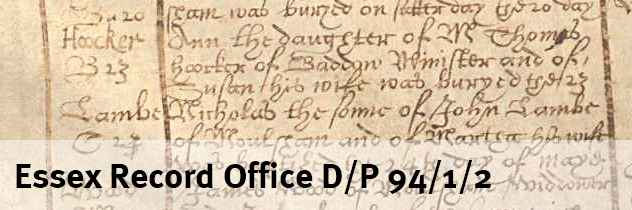

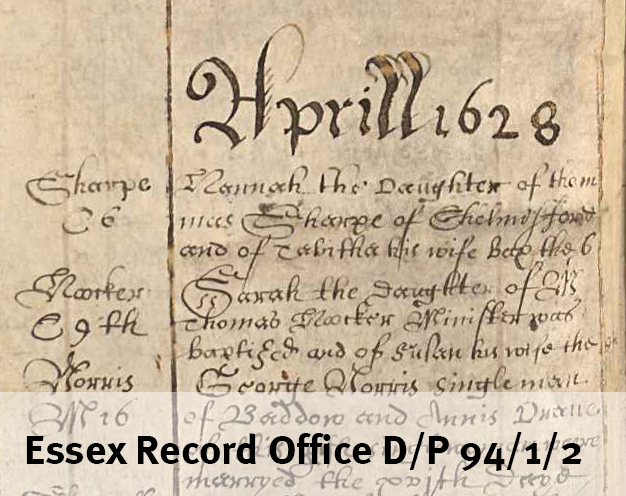

In about 1625 Hooker and his wife Susannah moved with their young family (at least one daughter, Joanna, and possibly their second daughter Mary) to Chelmsford, where Hooker had been appointed as town lecturer. The couple had four more children while living in Chelmsford, two of whom died in infancy and whose baptisms and burials are recorded in the local parish registers. The family lived at Cuckoos in Little Baddow just outside Chelmsford, a farmhouse which is still standing today.

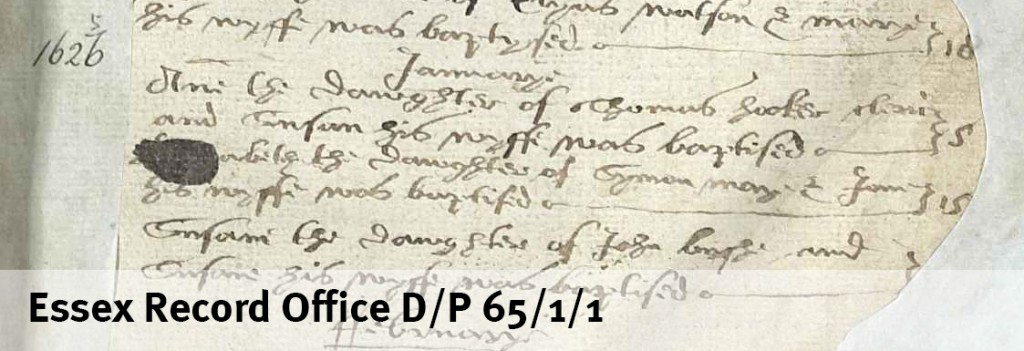

‘Ann the daughter of Thomas Hooker and Susan his wyff was baptised’, January 1626, Great Baddow (D/P 65/1/1, image 28)

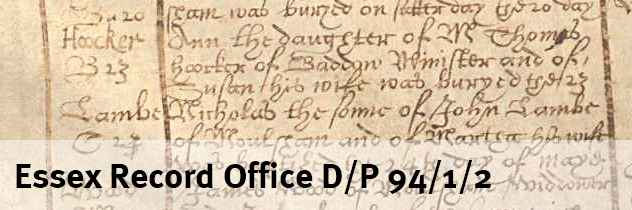

Burial record for ‘Ann the daughter of Mr Thomas Hooker of Baddow Minister and of Susan his wife’ from the Chelmsford parish register, 23 May 1626 (D/P 94/1/2, image 90). She would have been about 5 months old.

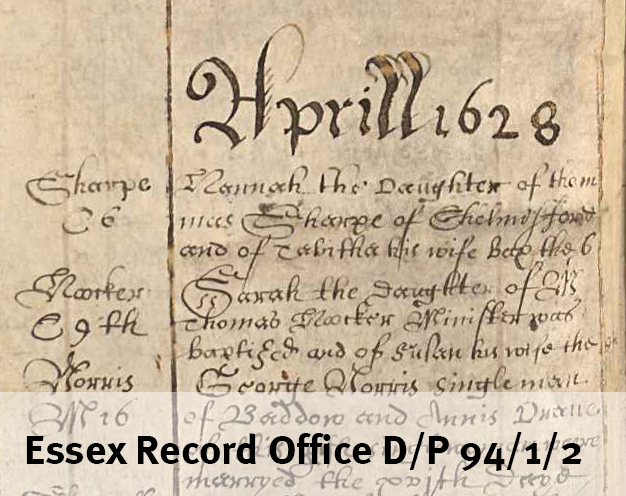

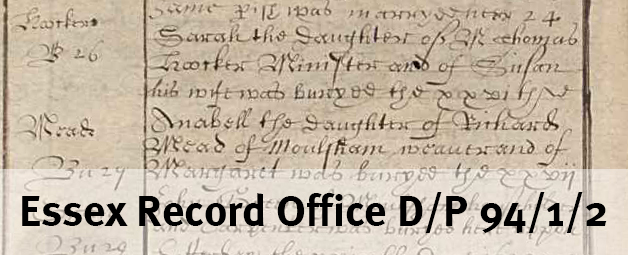

Baptism of Sarah Hooker, 9 April 1628, Chelmsford (D/P 94/1/2, image 95)

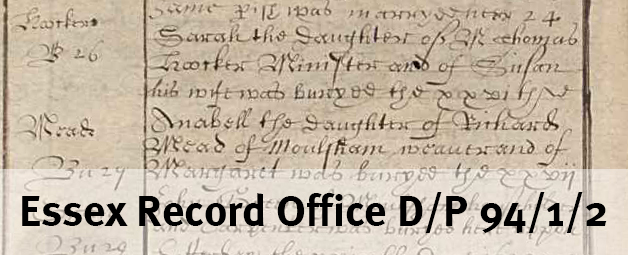

Burial of Sarah Hooker, 26 August 1629, Chelmsford (D/P 94/1/2, image 99). She would have been about 16 months old.

Cuckoos farm house, Little Baddow, home to the Hooker family during their time in Chelmsford (Photo: Peter Kirk)

Hooker’s duties in Chelmsford included two lectures a week, which people came from miles around to hear, including from the great families of Essex such as the Earl of Warwick who had a house in Great Waltham, near Chelmsford. Many of the people who came to listen to Hooker also made the journey to New England themselves, meeting him there again, becoming known as ‘Mr Hooker’s Company’.

Hooker spoke against some of the doctrines of the Church of England and the way it was organised, believing it was too close to Roman Catholicism.

Puritans did not seek just reform within the church, but also moral reform within society. The Chelmsford in which Hooker lived had a population of about 1,000, and more than its fair share of ale houses. Drunkenness was a particular focus of the Puritans. According to Magnalia Christi Americana: or, the Ecclesiastical History of New England (published in 1820 in Hartford, Connecticut):

‘there was more profaneness than devotion in the town and the multitude of inns and shops… produced one particular disorder, of people filling the streets with unseasonable behaviour after the public services of the Lord’s Day were over. But by the power of his [Hooker’s] ministry in public, and by the prudence of his carriage in private, he quickly cleared the streets of this disorder, and the Sabbath came to be very visibly sanctified among the people.’

Since this was written some 200 years later in the state where Hooker became a hero this needs to be treated with some caution, but gives an insight into views on Hooker over the centuries.

Bishop Laud and Hooker’s flight to Holland

William Laud, Bishop of London from 1628 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633

During Hooker’s time in Chelmsford, in July 1628 William Laud was appointed Bishop of London (he would go on to become Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633). Essex was still part of the Diocese of London, and Laud set about weeding out Puritan clergy.

Hooker’s reputation was spread and he was widely known to attract large crowds to his Puritan sermons. Hooker was called before the Court of High Commission in London and dismissed from his Chelmsford job. Withdrew to Little Baddow and set up a school in his house, but did still preach at St Mary’s in Chelmsford, despite the ban.

He was called before the Court of High Commission again, but fled to Holland in spring 1631. Susannah and the children were taken in by the Earl of Warwick in Great Waltham.

Before he left he preached a farewell sermon to the congregation at Chelmsford, which was printed in 1641 as The Danger of Desertion: Or A Farewell Sermon of Mr Thomas Hooker, Sometimes Minister of Gods Word at Chainsford in Essex; but now of New England. Preached immediately before his departure out of Old England. He had a warning for his listeners: “Shall I tell you what God told me? Nay, I must tell you on pain of my life. God has told me this night that he will destroy England.”

New England

After two years of separation, Thomas Susannah and their four surviving children set sail for New England on 10 July 1633 on the Griffin.

About 200 passengers were on board, including other influential men who would play their part in shaping the new world. The voyage was part of what became known as the Great Migration of 1629-40, during which about 20,000 people left England for America, mostly to seek freedom to practice their religion.

The Hookers first went to Newtown (now Cambridge) just outside Boston, where they were joined by several people described as ‘Mr Hooker’s Company’, whom they had known in Essex. Hooker was ordained as the pastor of the congregation on 11 October 1633. In 1636 the decision was made to move again and establish another Newtown (which was to become Hartford) in the Connecticut river valley.

As the English colonies proliferated (despite the presence of Native Americans and Dutch and French settlers) questions of government were under constant discussion, and Thomas Hooker played an active part.

A sermon by Hooker in which he declared that “The foundation of authority is laid in the free consent of the people” is widely credited as the inspiration behind the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut of January 1639, which in turn is seen as an important precursor to the current US Constitution.

Thomas Hooker died on 7 July 1647, 14 years after his arrival in New England. John Winthrop, Governor of Massachusetts and leader of the Winthrop Fleet which had sailed over in 1630, wrote after Hooker’s death that:

‘Mr Hooker who for piety, prudence, wisdom, zeal, learning, and what else might make him serviceable – might be compared with men of the greatest note – and he shall need no other praise.’

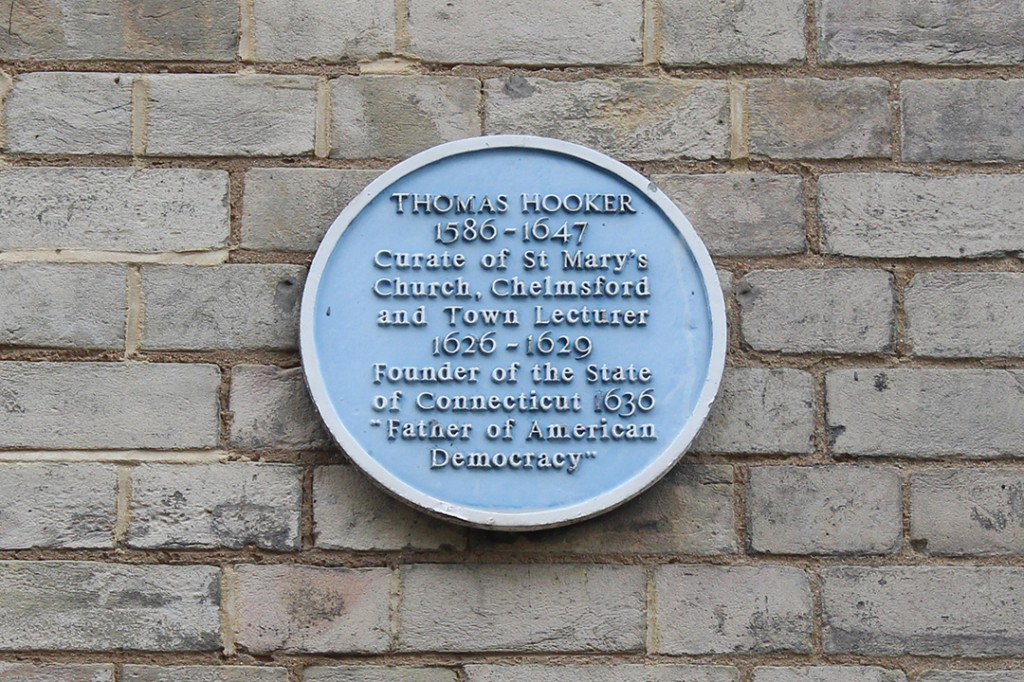

Plaque commemorating Thomas Hooker’s life in Chelmsford, on entrance alleyway to Chelmsford Cathedral

If you would like to know more about Thomas Hooker, Deryck Collingwood’s very detailed study Father of American Democracy: Thomas Hooker, 1586-1647 is available in the ERO library. You could also see Hubert Ray Pellman’s thesis Thomas Hooker: A Study in Puritan Ideals, which is catalogued as T/Z 561/35/1.

For an introduction to the Essex contribution to the early days of America, try John Smith’s Pilgrims and Adventurers: Essex (England) and the making of the United States of America, which is available in the ERO library, and also available to purchase from the Searchroom or by calling 033301 32500.

David M. Powers is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, and a graduate of Carleton College and Harvard University. His book, Damnable Heresy: William Pynchon, the Indians, and the First Book Banned and Burned in Boston, offers the first comprehensive biography of Pynchon. Placing Pynchon within the fabric of his times, Powers traces his life from Chelmsford, through his New England adventures, to his return to Britain, and describes contributions Pynchon made to the Puritan experience in Old England and New.

David M. Powers is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, and a graduate of Carleton College and Harvard University. His book, Damnable Heresy: William Pynchon, the Indians, and the First Book Banned and Burned in Boston, offers the first comprehensive biography of Pynchon. Placing Pynchon within the fabric of his times, Powers traces his life from Chelmsford, through his New England adventures, to his return to Britain, and describes contributions Pynchon made to the Puritan experience in Old England and New.