Lawrence Barker, Archivist

This month’s document has been chosen to mark National Tree Week, 24th November to 2nd December 2018, the UK’s largest annual tree celebration marking the start of the winter tree planting season. The document is the sale catalogue dating from 1923 for the Hallingbury Estate (SALE/A316). The estate included Hatfield Forest.

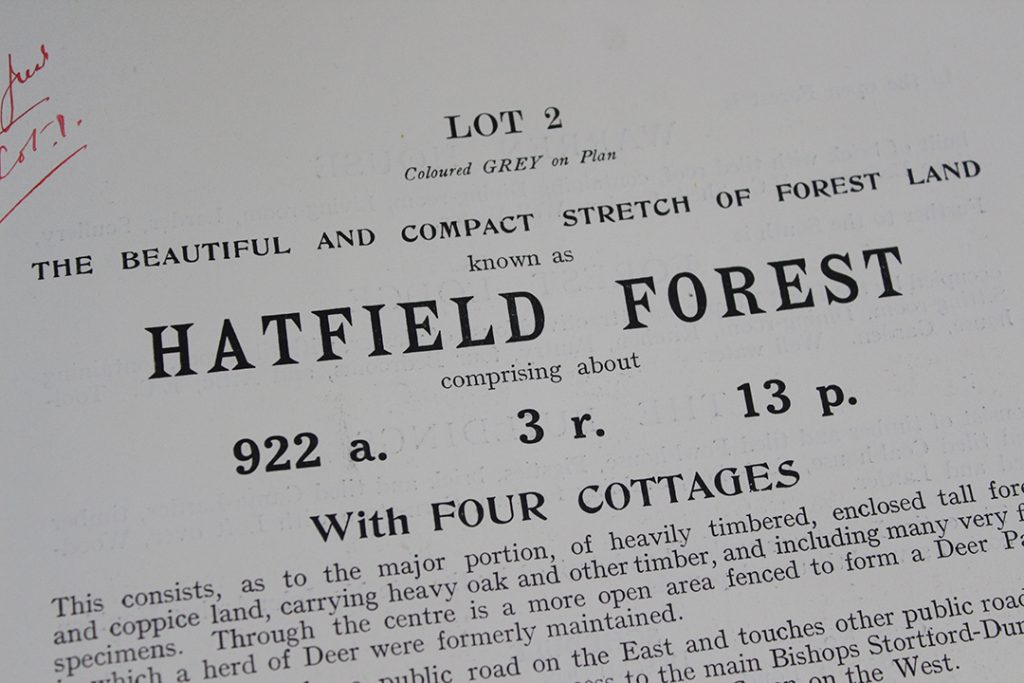

The part of the sale catalogue describing Hatfield Forest. The lot was over 922 acres, and included several cottages and a shell room or grotto,

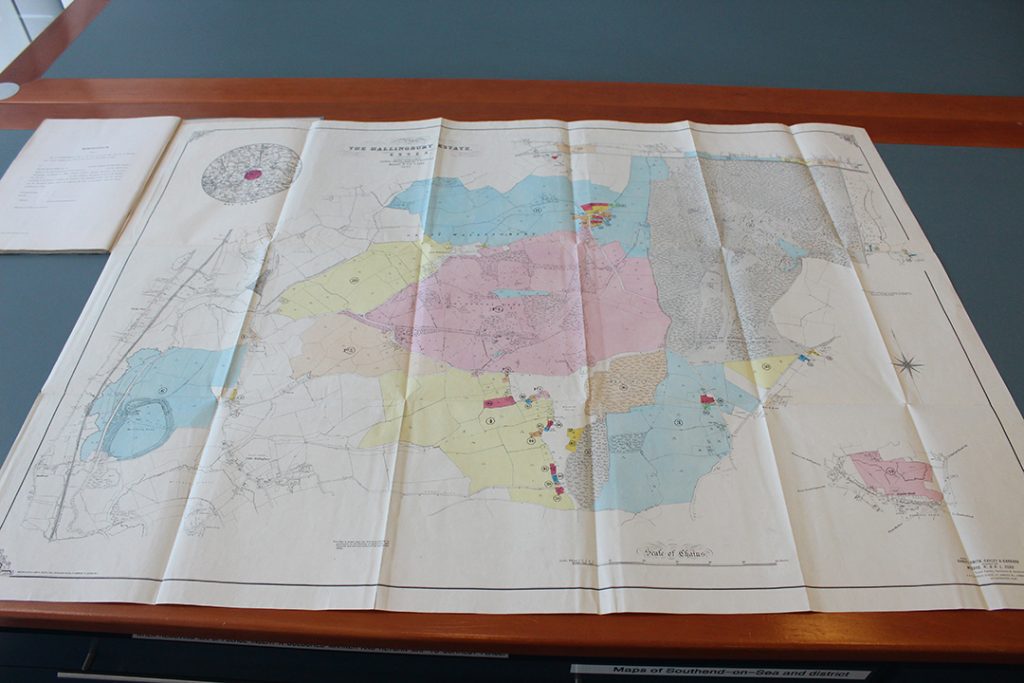

The sale catalogue includes a large fold-out map which shows how big the estate being sold was. Hatfield Forest is the area coloured in grey in the top right corner.

In his book entitled The Last Forest, 1989, Oliver Rackham begins by quoting from a previous book of his; ‘Hatfield is of supreme interest in that all the elements of a medieval Forest survive: deer, cattle, coppice woods, pollards, scrub, timber trees, grassland and fen, plus a seventeenth-century lodge and rabbit warren. As such it is almost certainly unique in England and possibly in the world. …The Forest owes very little to the last 250 years. … Hatfield is the only place where one can step back into the Middle Ages to see, with only a small effort of the imagination, what a Forest looked like in use.”

The sale catalogue draws attention to the timber ‘of very considerable value, the wood having been carefully managed for many years’. Many years indeed, as the Domesday survey of 1086 shows that it belonged to Earl Harold during the reign of Edward the Confessor before passing to William 1st after the conquest. Thus it became a ‘royal’ forest, part of the Forest of Essex which included Epping and Hainault, and alongside provision of timber it was used by the kings for hunting purposes. The chief beasts of the chase were red, roe and, particularly, fallow deer which still populate Hatfield Forest today.

Henry III was the first king to part with the forest and it passed down through the families of Bruce, de Bohun, the earls of Stafford and the Dukes of Buckingham. At one point, Robert the Bruce owned it before it was forfeited along with the rest of his lands in England when he became King of Scotland (the story is featured in this earlier blog posted in August 2014 featuring some of the oldest ‘Essex’ documents kept by ERO). Eventually, along with much of Hallingbury and Hatfield, it came into the possession of the Houblon family who developed it as park during the eighteenth century, creating the lake, planting ornamental trees such as horse chestnuts and building the charming shell house. The family later invoked the Enclosure Act of 1857 and paid £3000 to take it out of common land and enclose it as a private park. Following a decline in their fortunes, however, it was put up for sale in 1923.

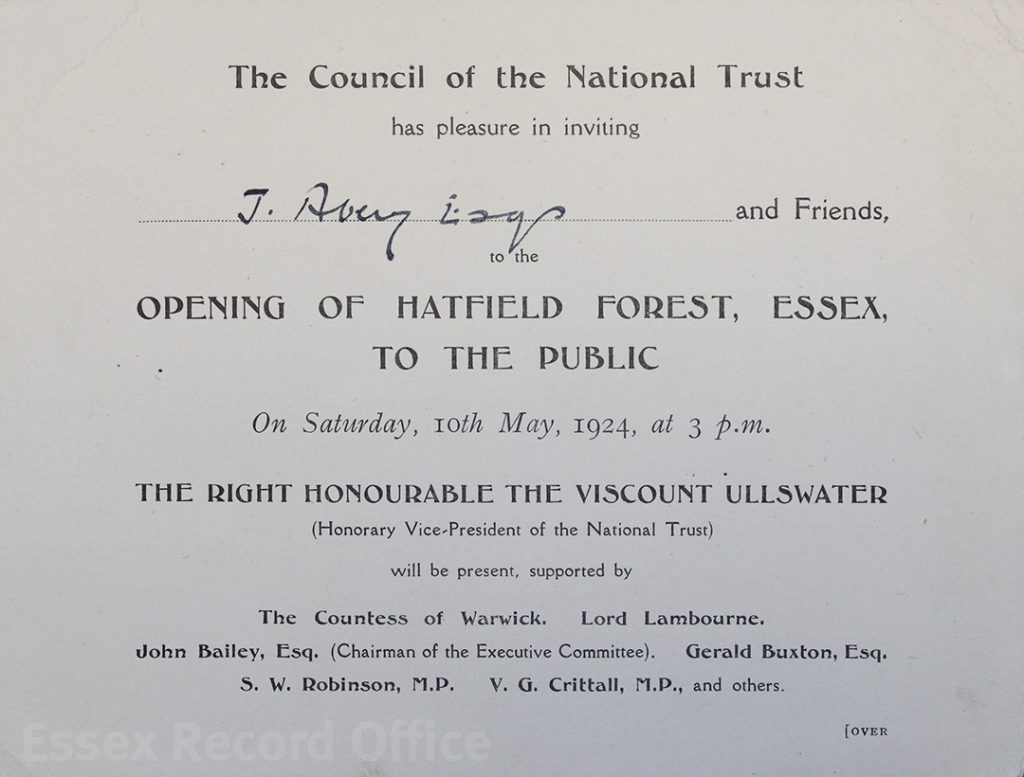

According to the National Trust, after an administrative error, a timber merchant bought Hatfield Forest and started felling the timber. At which point, the 83-year-old Edward North Buxton, a council member of the National Trust and a life-long preserver of forests helping to save Epping Forest of which he was a verderer, stepped in to save Hatfield Forest too. He managed to purchase it with the help of his sons from his deathbed and then give it to the National Trust. It was first opened to the public by Lord Ullswater on the 10th May 1924.

An invitation to the public opening of Hatfield Forest in 1924

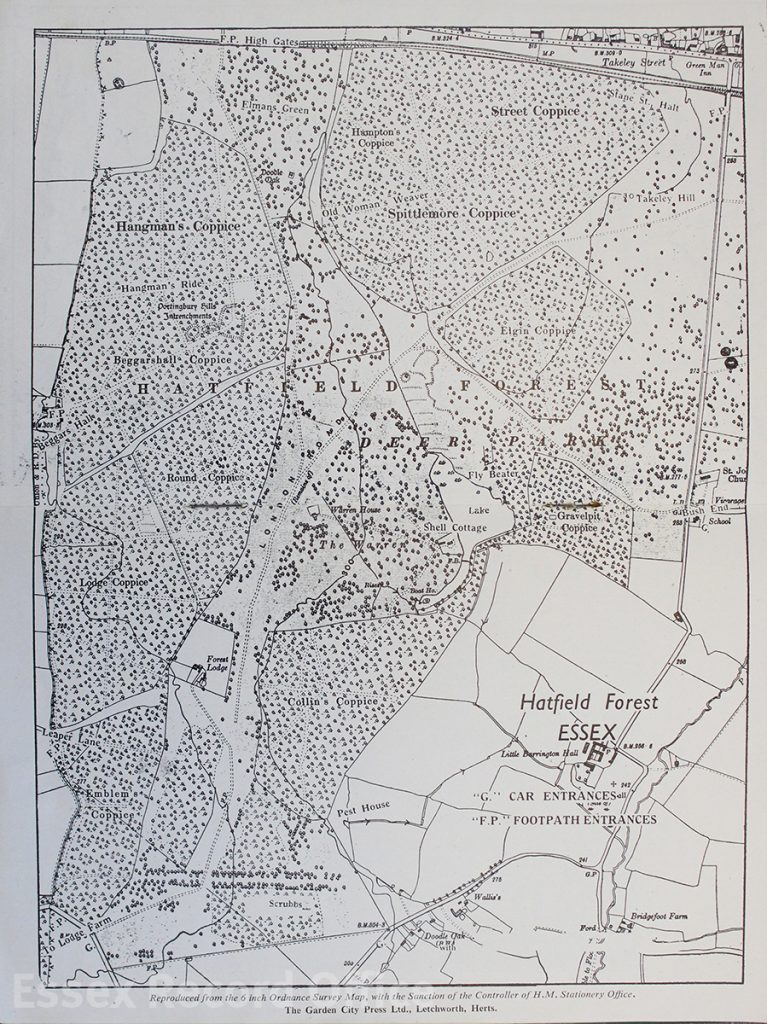

A map of Hatfield Forest from a 1952 National Trust guide

The forest is famous for its splendid oaks which acted as standard trees amid the coppices. One of the legendary trees was the Doodle Oak which in 1813 measured 60 feet in circumference. Unfortunately, by 1924 it had disappeared. At first the National Trust adopted a laissez-faire approach to preserving the forest but quickly realised that in order to preserve it properly, it would have to be managed as a working forest, especially with regular cutting of timber in the coppices, thereby preserving it in the same way it has been worked for nearly a thousand years.

The sale catalogue, guide book map and invitation will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout December 2018. You can find out how you can visit this ancient forest on the National Trust website.