New fragments which tell us about Essex’s past come in to us all the time, in all shapes and sizes. Here, Archivist Ruth Costello tells us about one of our new additions – a beautiful survey of the Rivenhall estate. The volume bears no date, so Ruth has been sleuthing to see if she could find out when it was made.

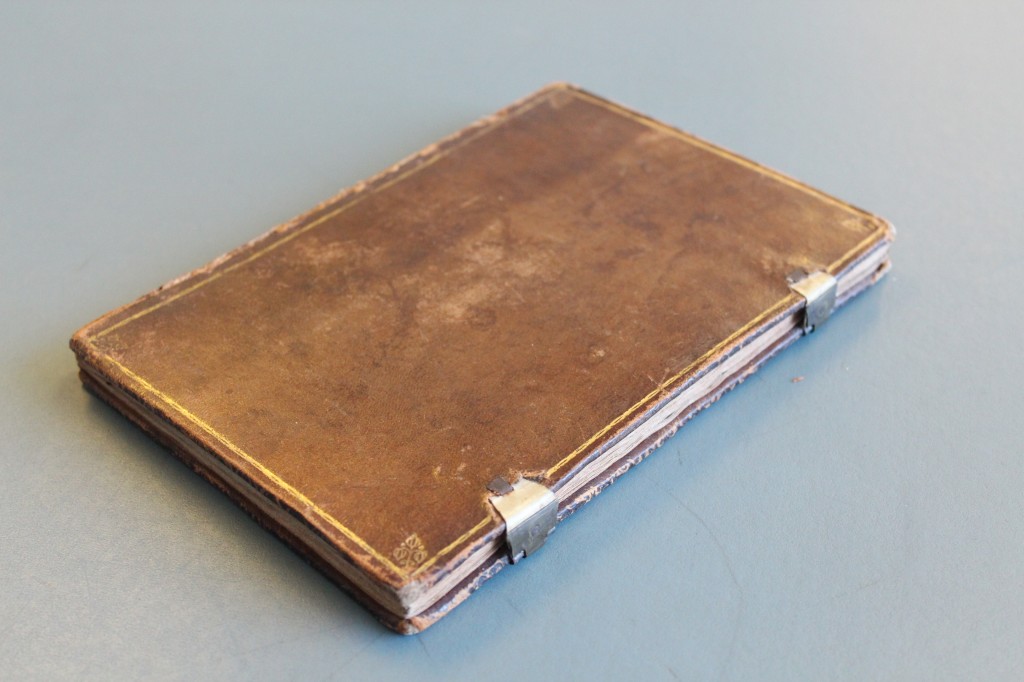

This month’s document is one of two volumes of maps which we received earlier this year as part of accession A14956. This, the smaller of the two, shows Rivenhall Place and its lands, which were owned by the Western family.

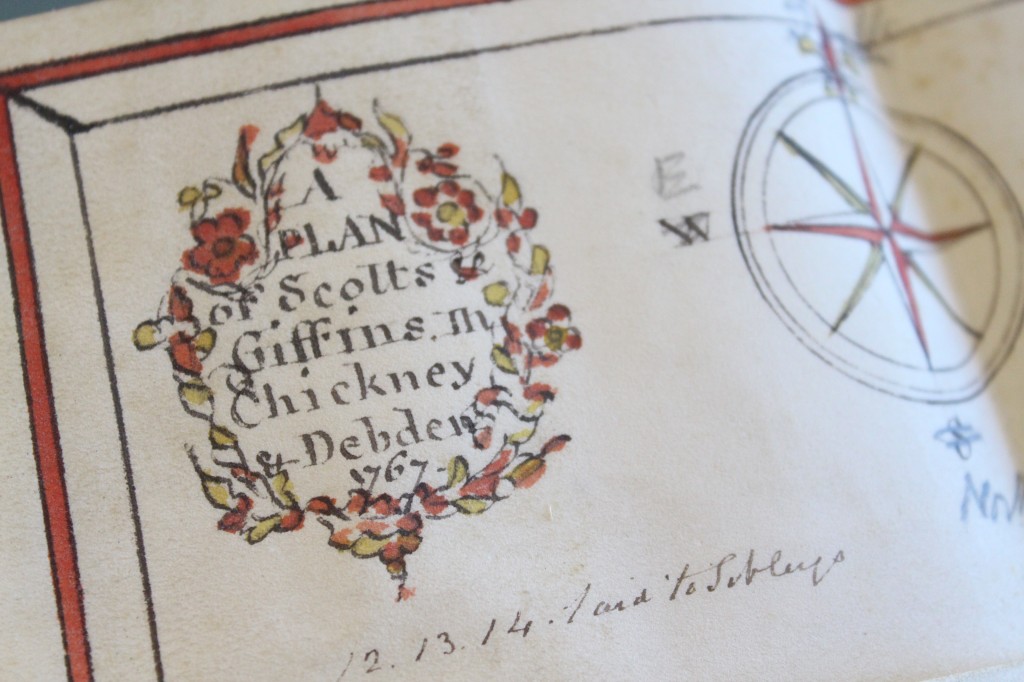

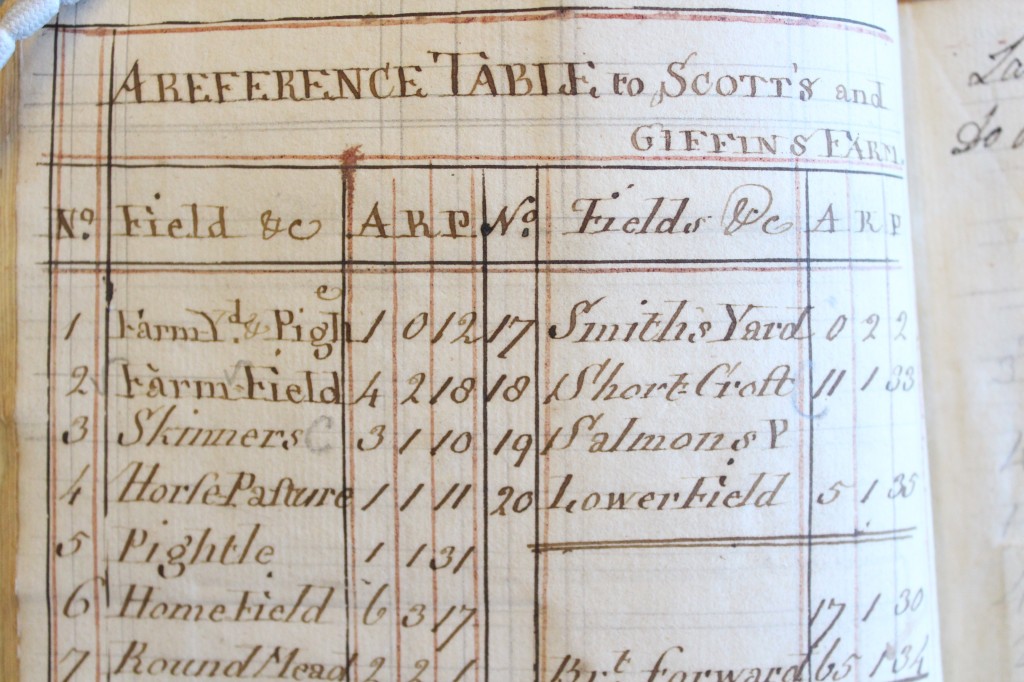

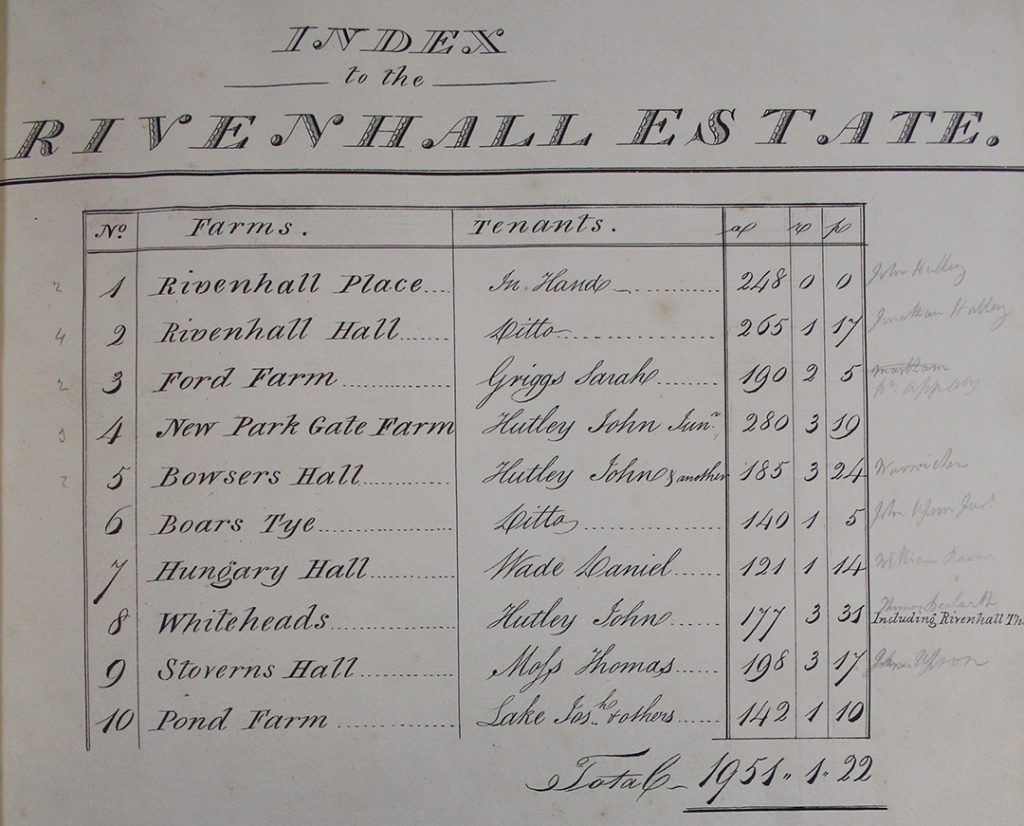

The index at the beginning of the volume lists the parts of the Rivenhall estate which are included in the survey

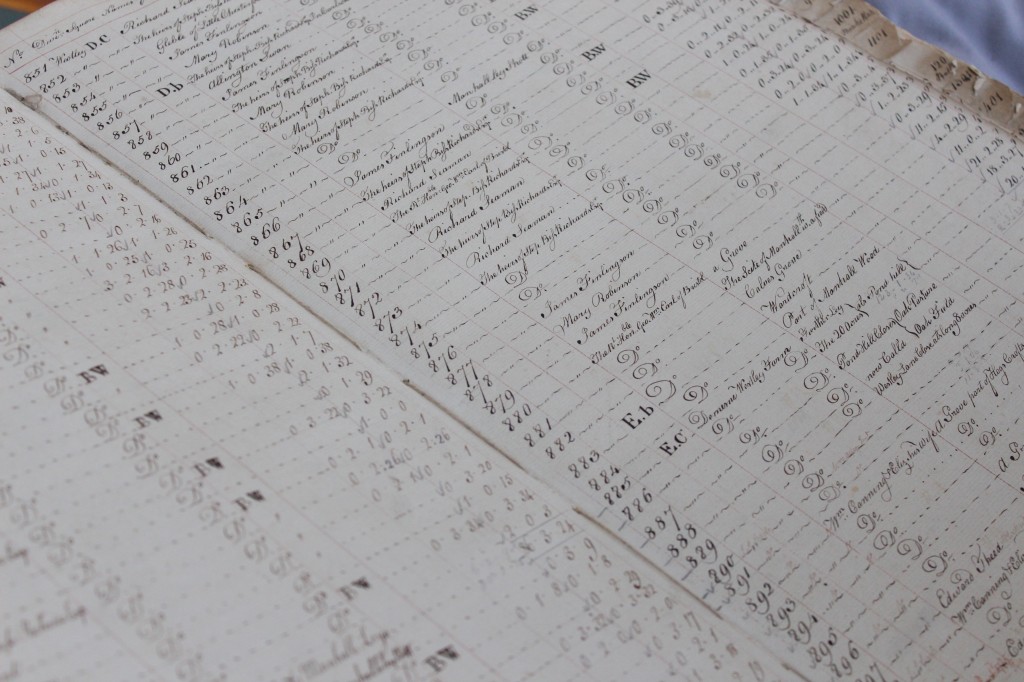

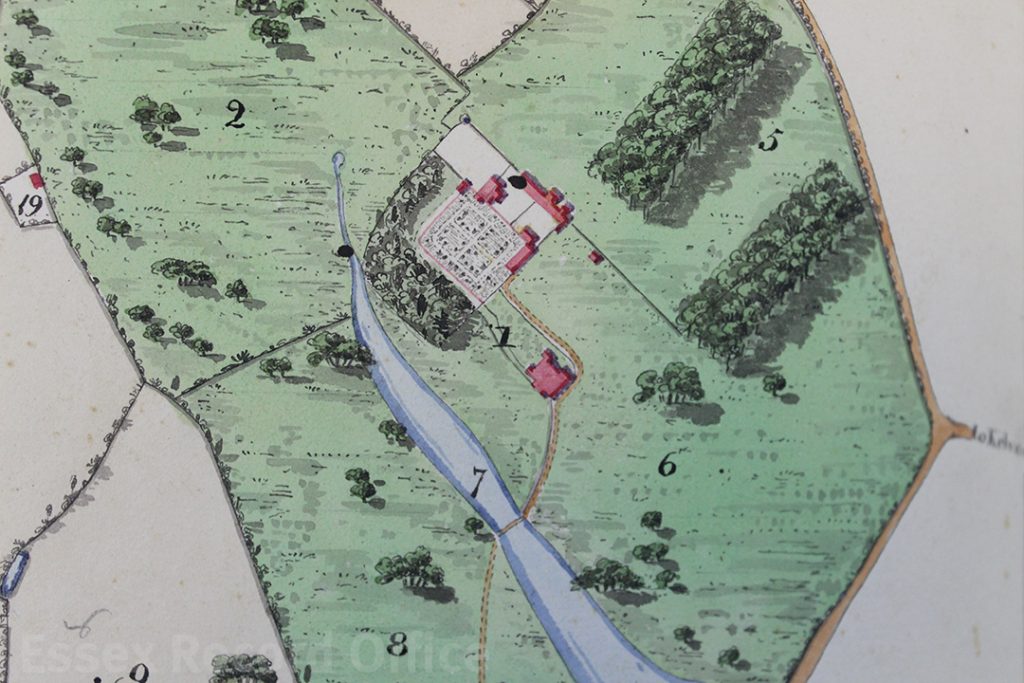

For each part of the estate, there is a carefully drawn map, and a list of how each parcel of land was being used. This map shows Rivenhall Place and the lands immediately around the grand house.

Despite its undoubted beauty, it seems to have been treated as a working document, with annotations in pencil, some of which seem to have been rubbed out at a later date.

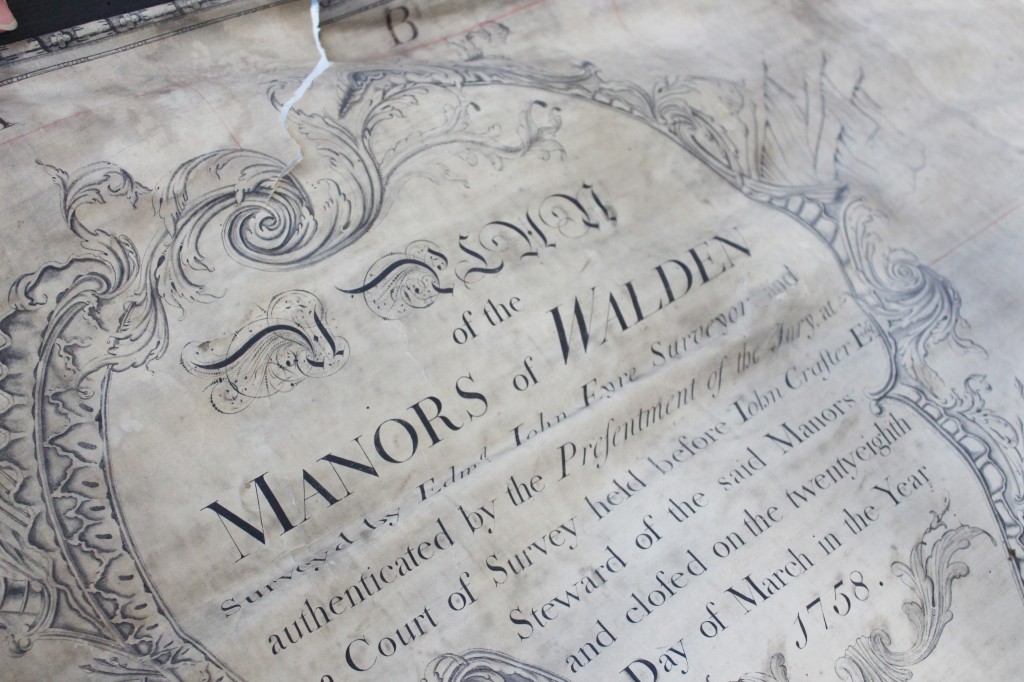

Unfortunately, the survey does not include a title page, where we might expect to find the name of the surveyor. Nor does it include a date.

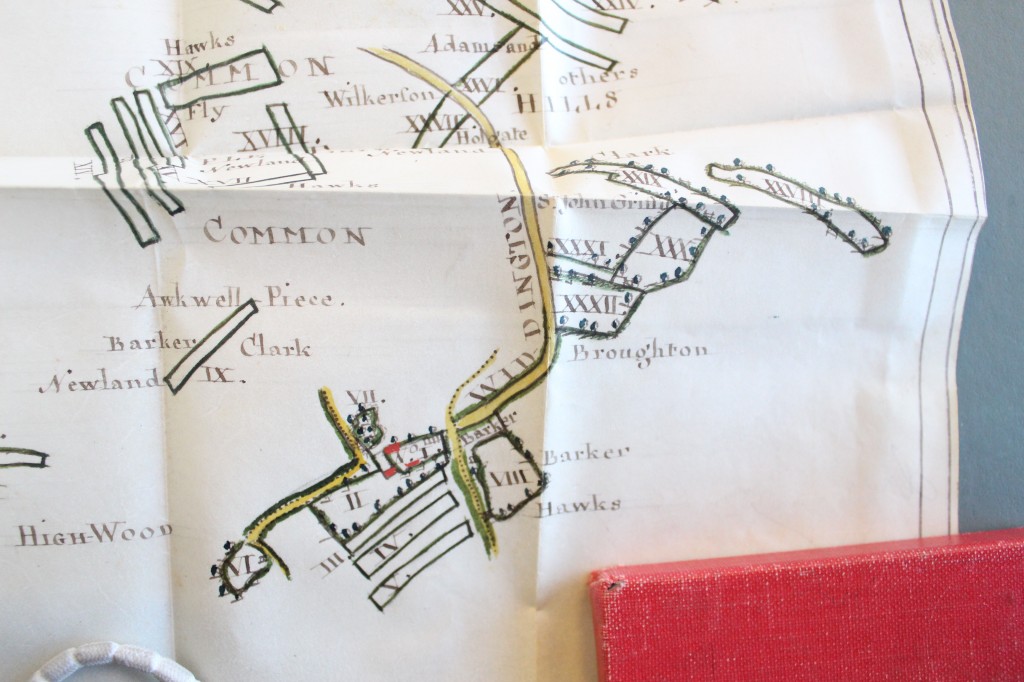

We knew the volume must predate 1839 as the Rivenhall tithe map produced in that year clearly shows the newly built Eastern Counties Railway running through the parish. In the volume, it has been pencilled in at a later date (it’s the line crossing through the meadow land numbered ‘23’, north of Rivenhall End in the page on display).

The two lines marked in pencil through field no. 23 on this map show where a railway line was later built, helping us to date the volume

We already held two maps of Rivenhall Place among the Western family estate records drawn in 1828 and 1839 (this latter one didn’t show the railway, so must have been produced earlier that year). It’s unlikely that the land would have been surveyed and mapped on another occasion, so we thought that the volume must tie in with the date of one of these maps.

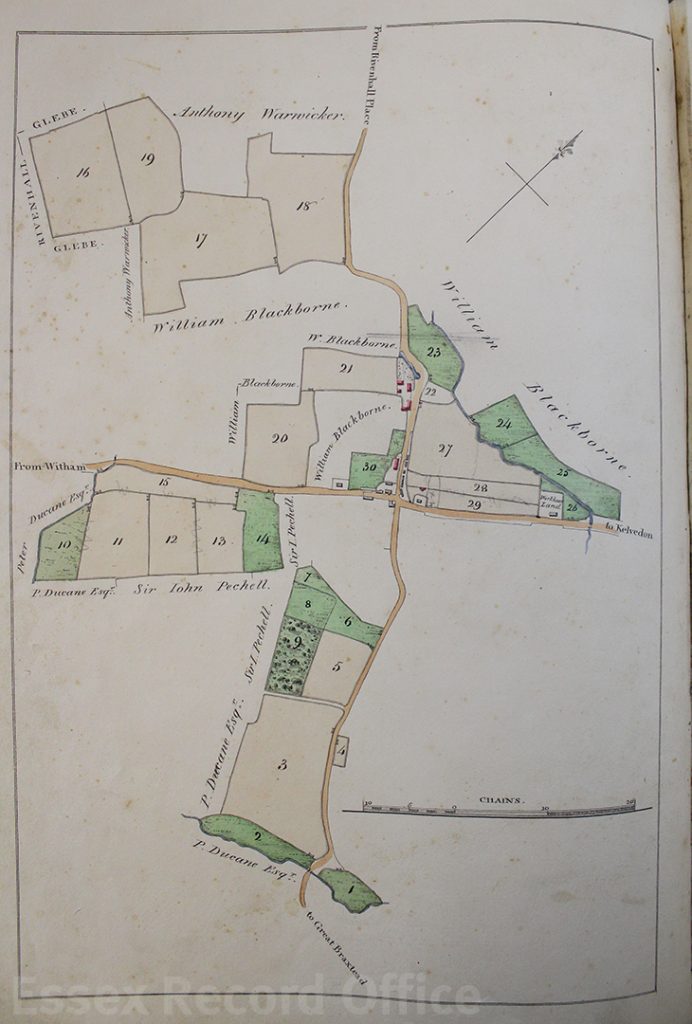

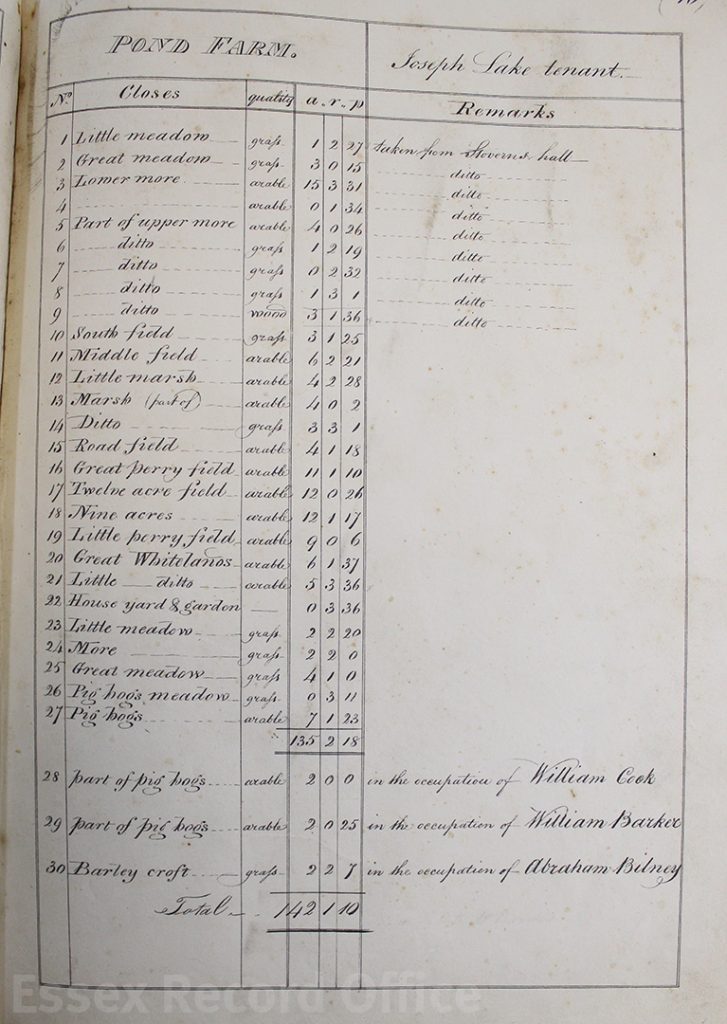

On display in the ERO Searchroom, the volume is opened to display the map of Pond Farm, which at the time was leased (somewhat appropriately) by Joseph Lake. Both the volume and the 1828 map (D/DWe P12) show a property described as ‘workhouse land’ (it’s surrounded on two sides by the field numbered ‘26’). The later map of 1839 (D/DWe P16) has the name ‘Bilney’ against this property. It would seem that Mr Bilney bought the property after the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 led to the sale of former, smaller parish workhouses and the creation in this case of the new Witham Poor Law Union workhouse.

Map of lands that made up Pond Farm

List of lands making up Pond Farm

Some of the surrounding area is described as ‘William Blackborne’s land’. We found a burial for a William Blackborne in the Rivenhall parish register in 1825. Initially this made us think that the volume must predate his death and must be earlier than 1825. However, both the 1828 and 1839 estate maps also included his name, which showed that out of date information was being copied forwards.

We think, therefore, that the volume and the 1828 map we already held were drawn at the same time. Sadly, we still don’t know who drew them; the map also has no author. The map shows the whole of the estate and its individual farms together, but it has only a very little colouring, by comparison with the volume. This volume and its companion (a series of maps of the Felix Hall estate) are thus a welcome addition to our holdings.

The volume will be in display in the Searchroom throughout September 2018.