As we mark the 100th anniversary of Britain’s entry into the First World War on 4 August 1914, we thought we would take a look back at the immediate reactions and concerns of Essex people to the outbreak of the war as portrayed in the Essex County Chronicle.

The first edition of the Chronicle to be published after the declaration of war was on 7 August. As well as giving us an insight into people’s thoughts on the war, the paper gives us an idea of the activities and occupations of people on the eve of the conflict.

A Bank Holiday had just passed, on which the Great Eastern Railway had conveyed 42,411 people to stations serving Epping Forest, and there had been shows and sports around the county. Essex’s status as an agricultural county is also evident; it was reported that Chelmsford was confirmed to be home to the third largest wheat market in the country, and Colchester the sixth largest. All was not well in the world of agriculture though; a farm labourers’ strike in north Essex had culminated in five haystacks being set alight in Steeple Bumpstead and Birdbrook in the weekend before the declaration of war.

All of these snippets of news, however, were overshadowed by news of the war, and speculation as to how Essex was going to be affected.

Views on the war

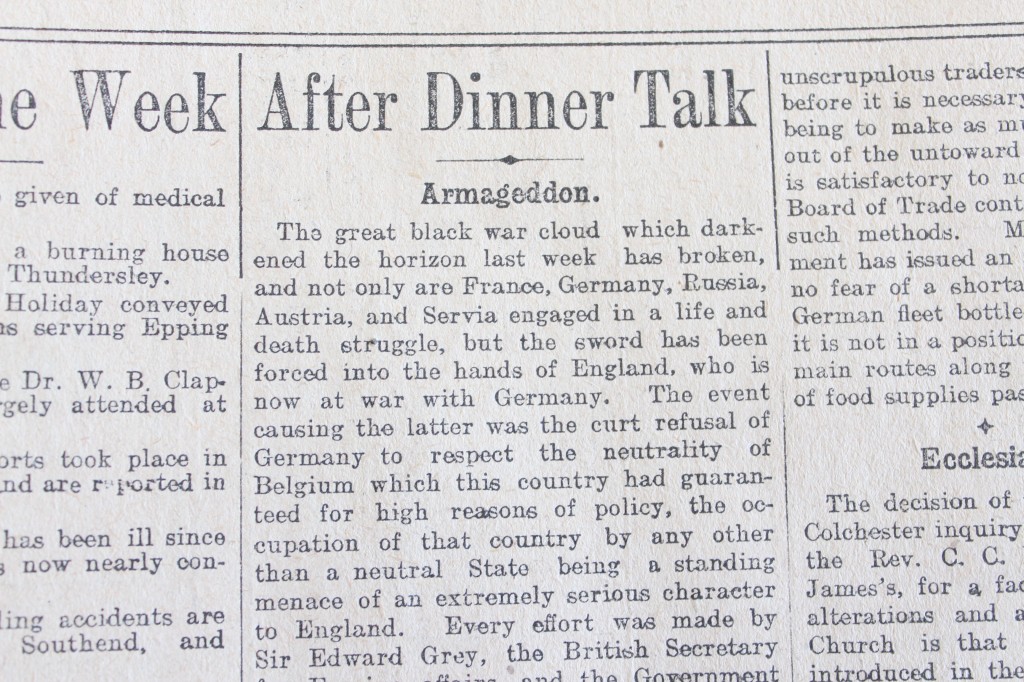

The paper explained briefly what had unfolded on the continent so far: the Archduke of Austria had been assassinated by ‘some mad youth said to be a member of one or other of the cut-throat Societies which abound in Servia’. The ensuing row between Austria and Serbia had escalated until Russia and Germany became involved, ‘and so the mad Dance of Death has begun’.

Some people clearly opposed the war entirely: ‘Sir Albert Spicer is among those who have expressed their willingness to give effective support to an organisation for insisting that this country shall take no part in a Continental war unless directly attacked.’

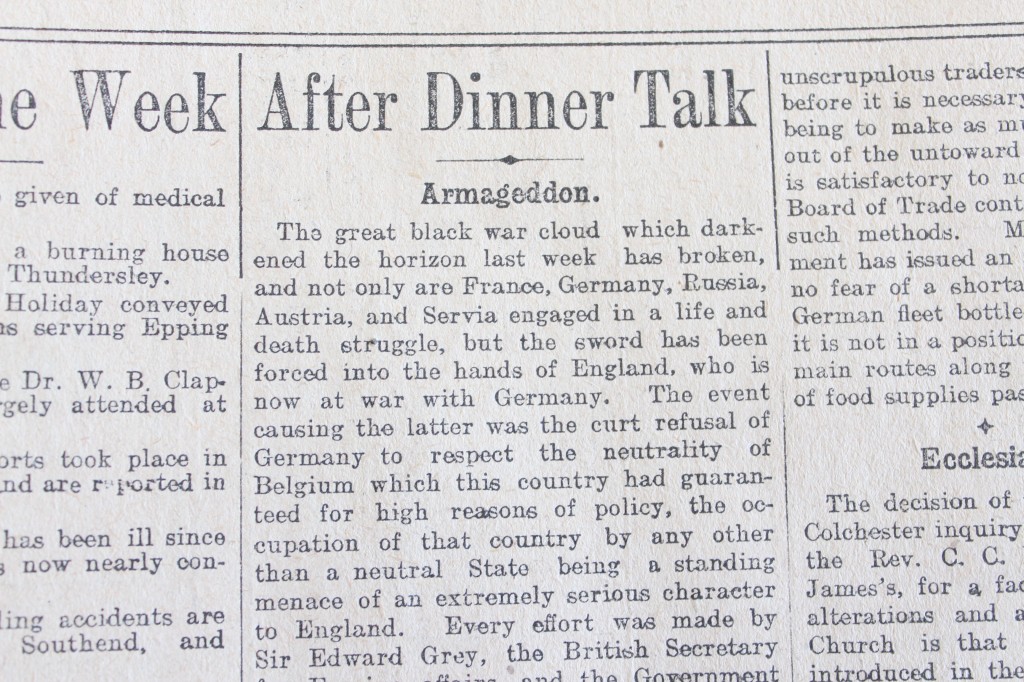

The overall impression given by the paper’s reporting on the war is that people were not happy about it, but they would do their duty. Under the heading ‘Armageddon’, one journalist described ‘the great black war cloud which [has] darkened the horizon’, and thought that everything had been done by Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, to ‘avoid joining the titanic struggle’. Germany’s invasion of neutral Belgium, he believed, had left Britain no choice.

The mood in Essex was described as serious, but calm:

‘There is no panic, no mafficking, nor jingoism; a calm, serious resolve seems to pervade Essex, as indeed the whole country, to meet the terrible arbitrament of war cast upon us unflinchingly and with high courage, and there is a feeling that the sword must not be sheathed again until it is placed beyond the role of any one power to attempt or desire to dominate others.’

This is maybe not a totally accurate description of the prevailing mood, as the paper also reports on fears of a German invasion and on people hoarding food.

Fear of invasion

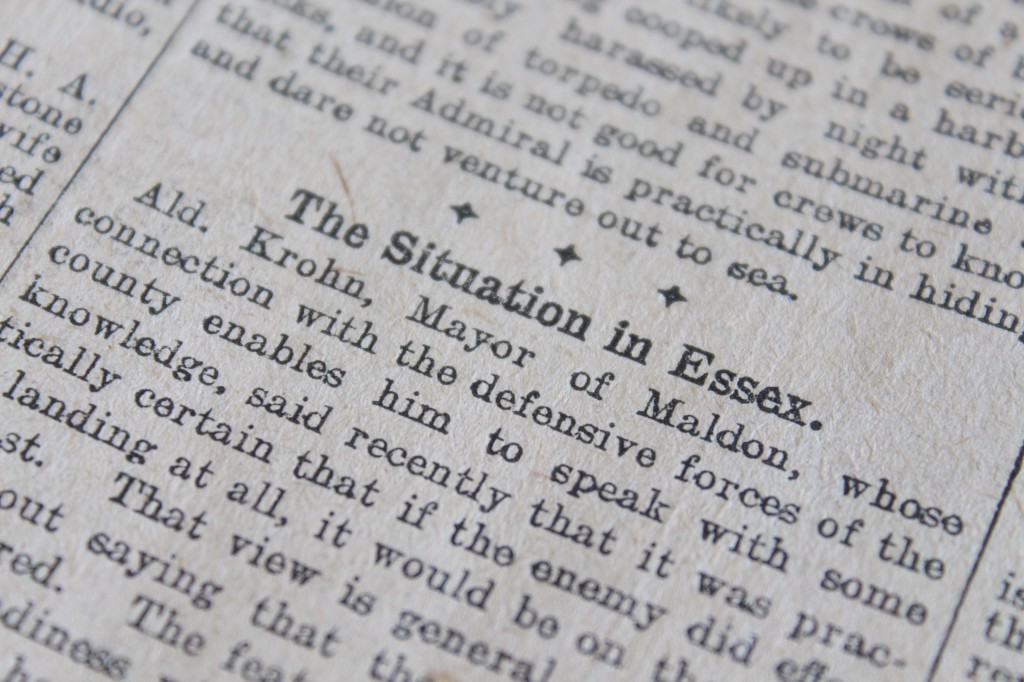

There was instantly some discussion in Essex about the possibility of a German invasion of England. The Mayor of Maldon, Alderman Krohn, was reported as saying that ‘it was practically certain that if the enemy did effect a landing at all, it would be on the Essex coast. That view is general, and it goes without saying that the authorities are prepared’. The idea that the authorities were prepared for a German invasion in August 1914 is not borne out by other sources, but that’s for another blog post.

Food hoarding and profiteering

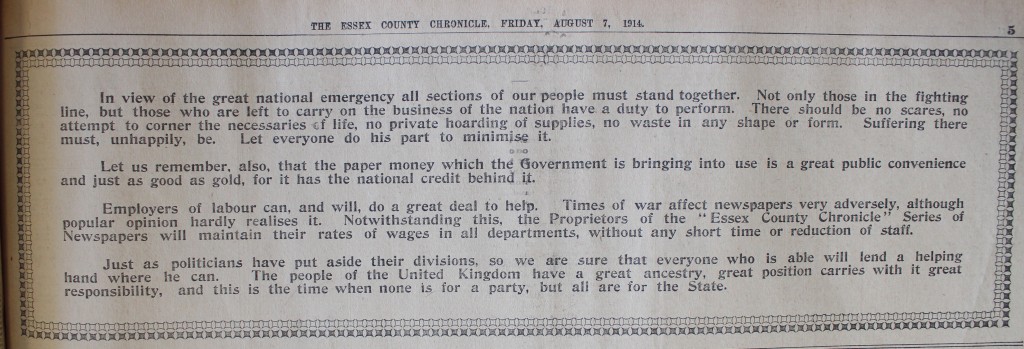

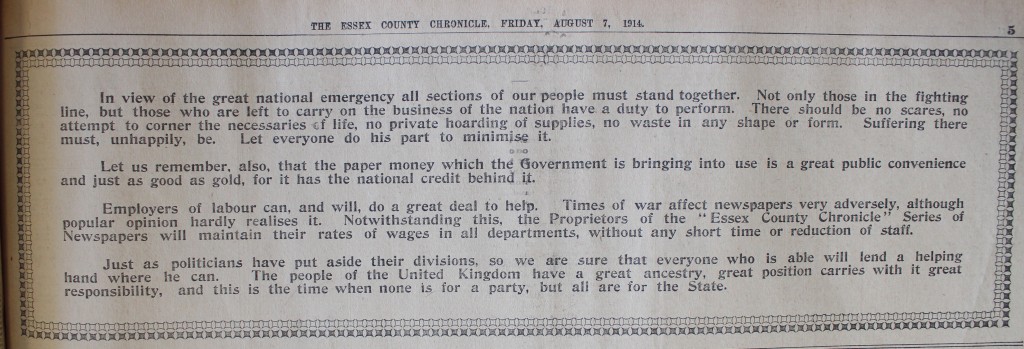

One of the principal concerns in Essex on the outbreak of war seems to have been the hoarding of food and profiteering. The page giving news of the war is dominated by a large notice at its head:

‘In view of the great national emergency all sections of our people must stand together. Not only those in the fighting line, but those who are left to carry on the business of the nation have a duty to perform. There should be no scares, no attempt to corner the necessaries of life, no private hoarding of supplies, no waste in any shape or form. Suffering there must, unhappily, be. Let everyone do his part to minimise it.’

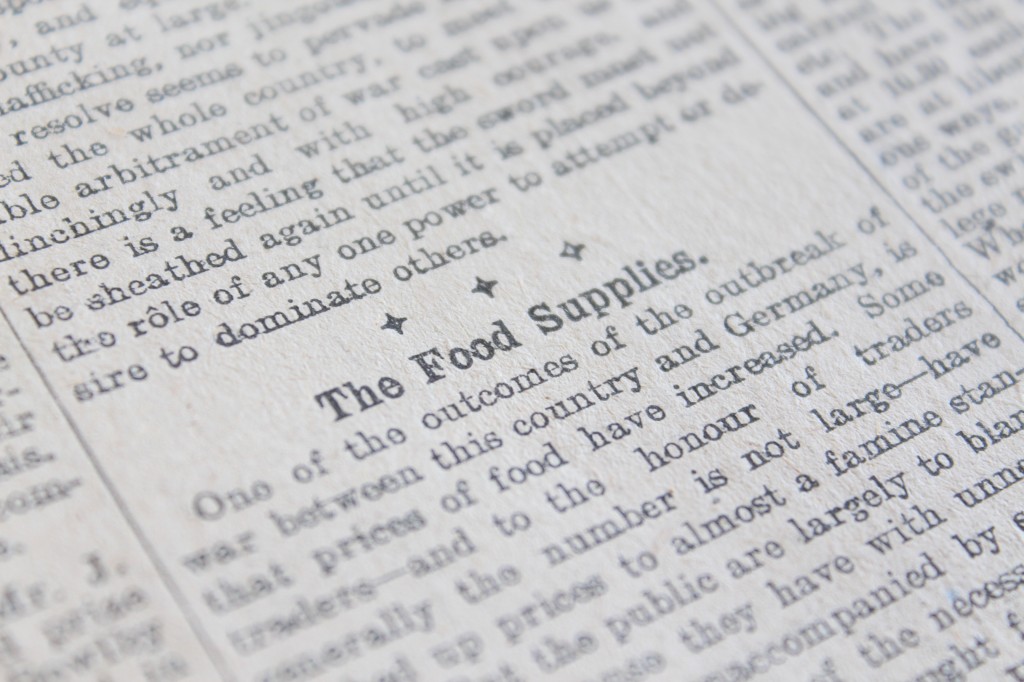

Food supplies are also mentioned in another segment on the page:

‘One of the outcomes of the outbreak of war between this country and Germany, is that prices of food have increased. Some traders – and to the honour of traders generally the number is not large – have rushed up prices to almost a famine standard. But the public are largely to blame for this, because they have with unnecessary panic, not unaccompanied by selfishness, bought heavily of the necessaries of life, without the least thought for others.’

Mr. J.J. Crowe, Chairman of Brentwood Urban Council, had commented that ‘Such wholesale buying of food and rushing to the bank … are not only unpatriotic but wicked’.

In the meantime, the Government had issued an assurance that there was no immediate danger of a food shortage; the German fleet was blockaded in the North Sea, and not in a position to interrupt the main routes through which British food supplies passed.

Looking back to the past

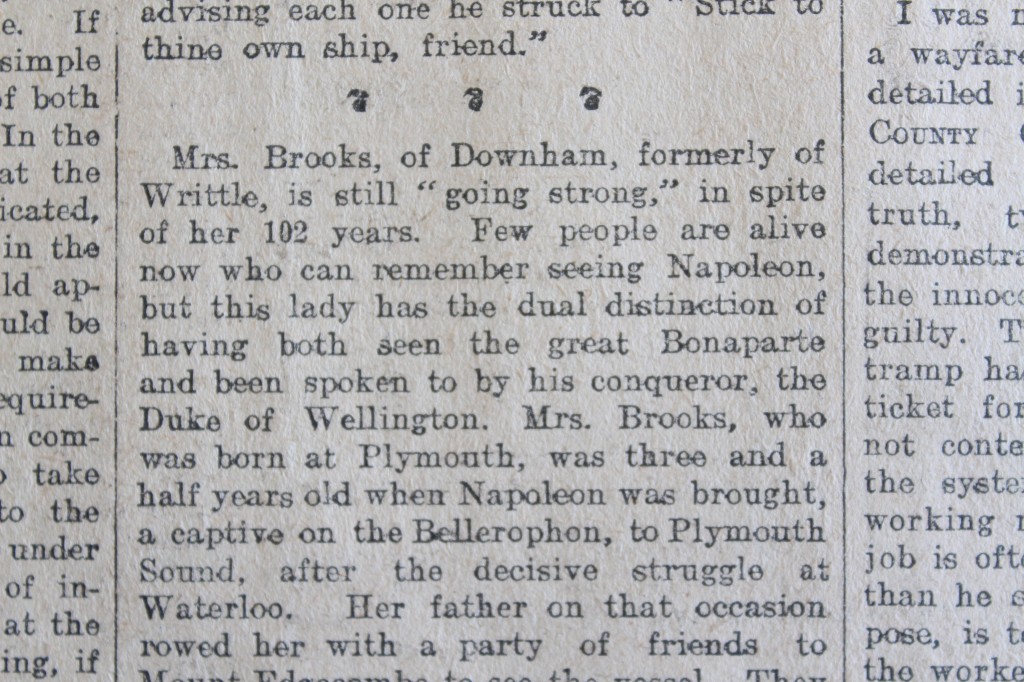

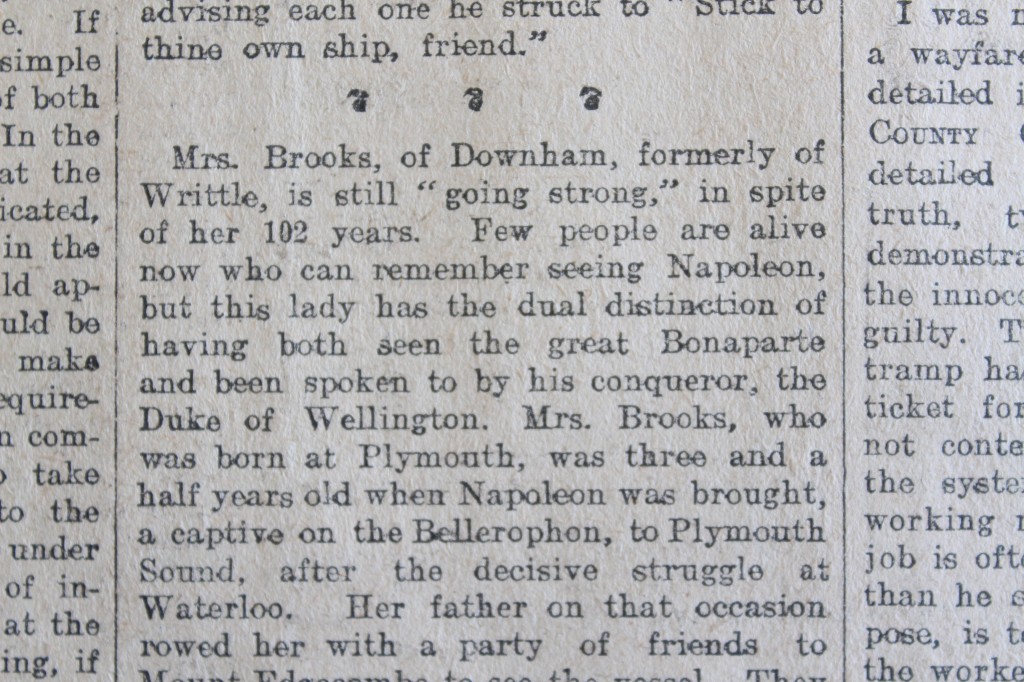

Just as we look back to the past of 100 years ago, so did the people of 1914. The Chronicle of 7 August included mention of a Mrs Brooks of Downham, apparently still going strong at the age of 102.

Mrs Brooks was distinguished by more than just her age:

‘Few people are alive now who can remember seeing Napoleon, but this lady has the dual distinction of having both seen the great Bonaparte and been spoken to by his conqueror, the Duke of Wellington.’

Mrs Brooks was born in Plymouth, and as a 3 ½ year old was taken by her father to see Napoleon as a prisoner on board the Bellerophon before he was taken to St Helena. When she was 17, she briefly met Wellington while visiting the Hon. Mrs Cotton, daughter of Lord Combermere.

‘It is no small coincidence that this venerable lady should have been born in the turmoil of a struggle which paralysed all Europe and should live to see the beginning of another which promises to be no less titanic.’

All images reproduced courtesy of the Essex Chronicle

To find out more about First World War records at ERO, join us at the following:

Discover: First World War records at ERO, Wednesday 6 August, 2.30pm-4.30pm (details here)

A Righteous Conflict: Essex people interpret the Great War – A talk for the Essex History Group by Paul Rusiecki, Tuesday 2 September, 10.30am-11.30am, free, no need to book

Essex at War, 1914-1918, a day of events at Hylands House, Sunday 14 September (details here)

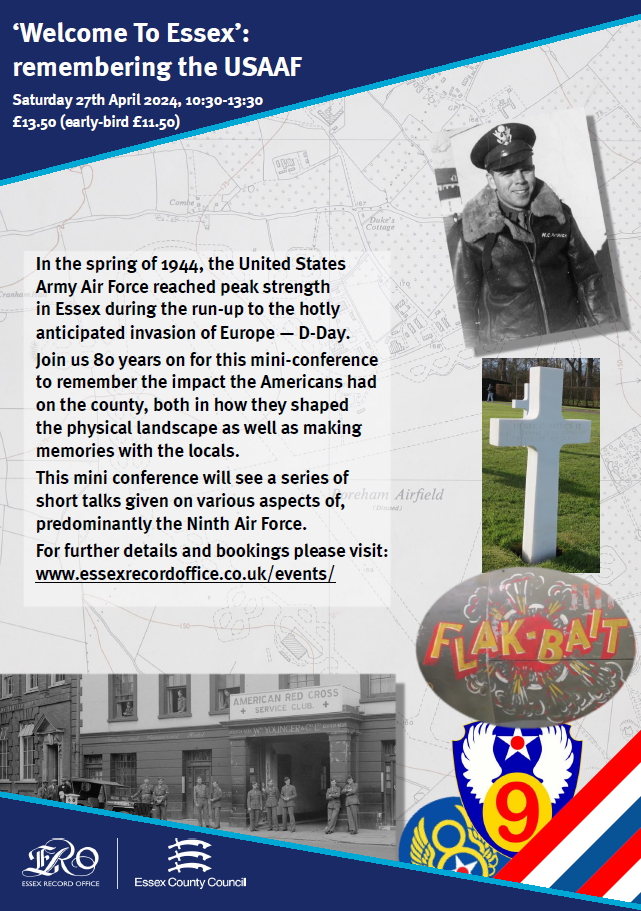

ill be a theme running through the event, the date on which it is being held being of particular significance to one of the speakers in relation to one of those Americans who flew out of Essex.

ill be a theme running through the event, the date on which it is being held being of particular significance to one of the speakers in relation to one of those Americans who flew out of Essex.