In this next installment in our mini series marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, Katharine Schofield investigates some of the documents we hold which show medieval kings raised their armies to fight the Hundred Years’ War. Find out more about Agincourt and the Essex gentry who took part at Essex at Agincourt, a one-day conference on Saturday 31 October 2015. This is a joint event with the Essex branch of the Historical Association, and all the details can be found here.

After the Norman Conquest society and most importantly land-holding was arranged on a feudal basis. William the Conqueror divided the English lands between his supporters, the tenants-in-chief named in the Domesday Book. They held their lands directly from the king in return for military service, generally considered to be a maximum of 40 days a year. In turn they rewarded their military supporters with land. This process called subinfeudation continued down through the landholding classes to the knight at the bottom. A knight’s fee was sufficient land to support a single knight. This would include the knight, his family and servants, as well as providing him with the means to provide horses and armour to perform his military service.

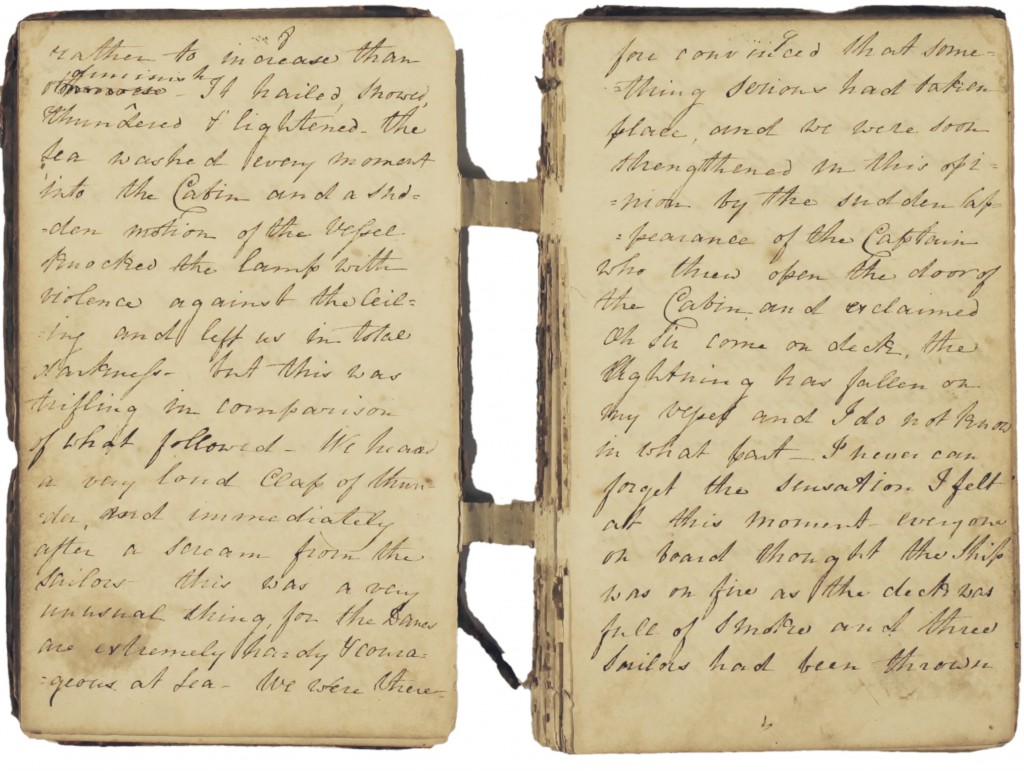

When a knight died without a male heir his lands could be divided between heiresses (and their husbands). The knight’s fee would be split into parts called moieties which owed fractions of a knight’s service. Since it is difficult to provide a fraction of a knight (at least before a battle), it gradually became customary for payment of scutage (literally shield money) to be made in place of military service. In some cases a payment would be made because the land was too divided, in others the landowner might be too old or too young to fight. The money would then be used to hire mercenaries to fight in wars.

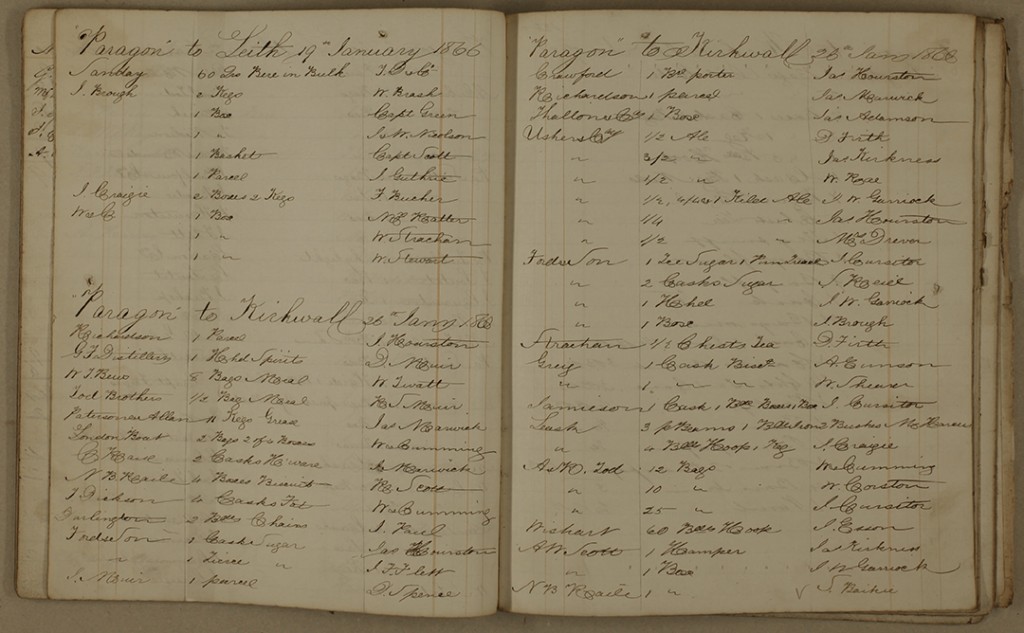

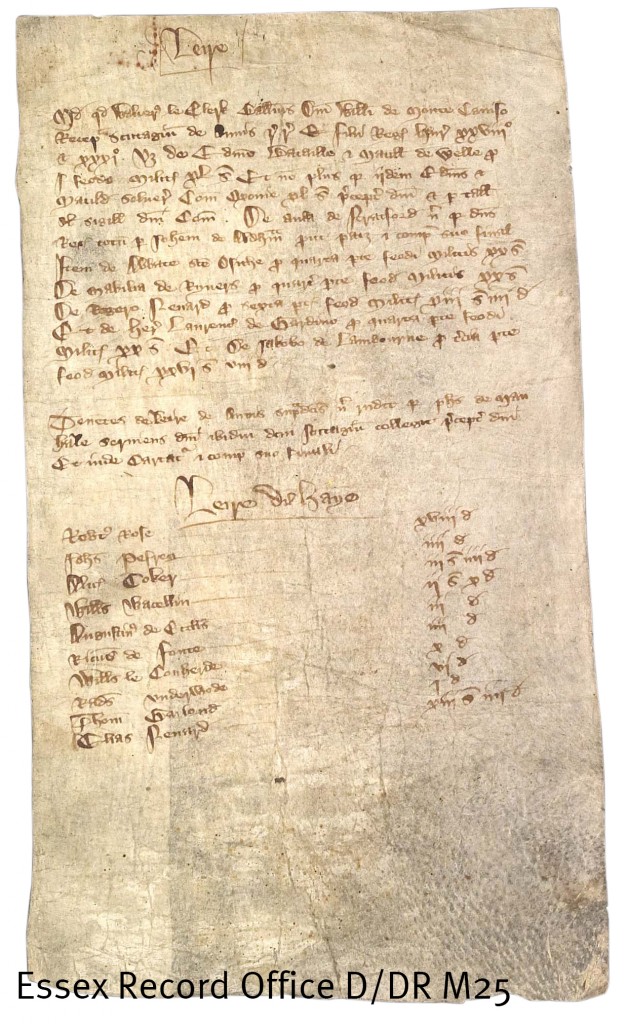

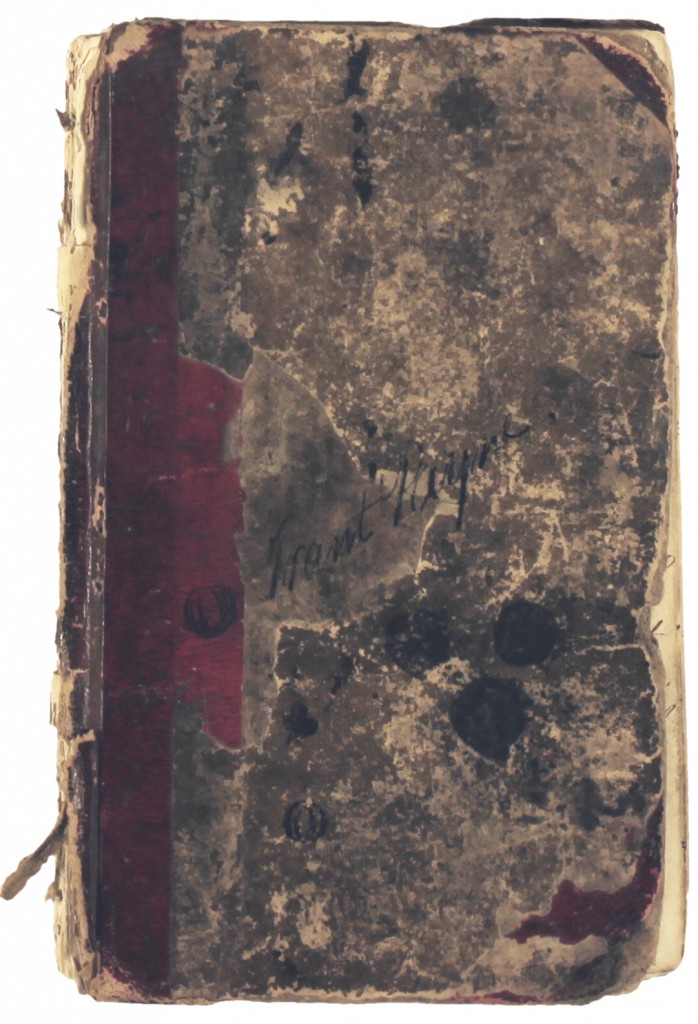

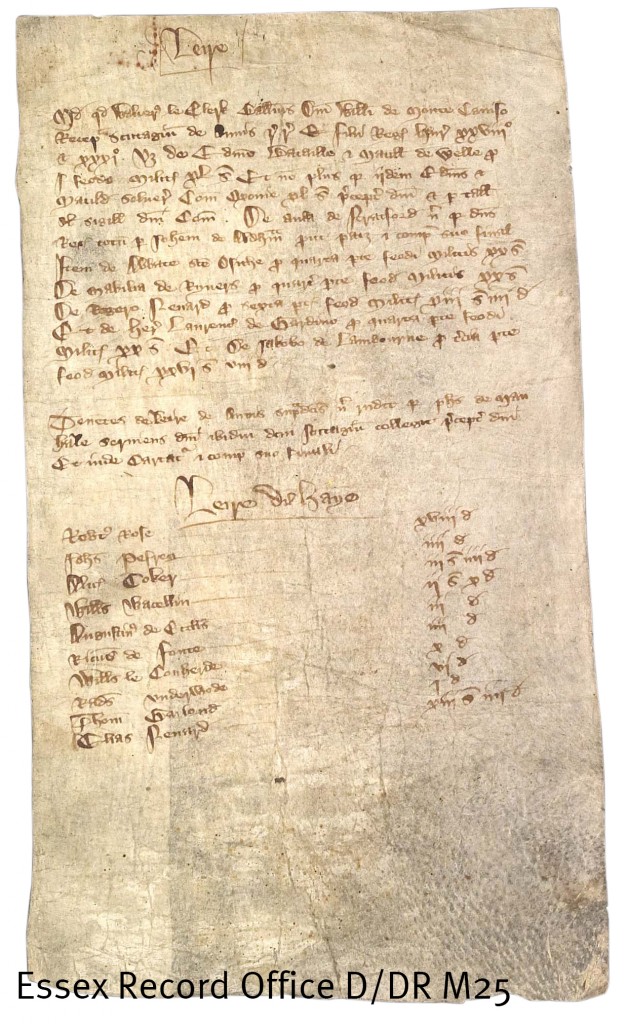

Scutage roll from Layer-de-la-Haye, 1240-1360 (D/DR M25)

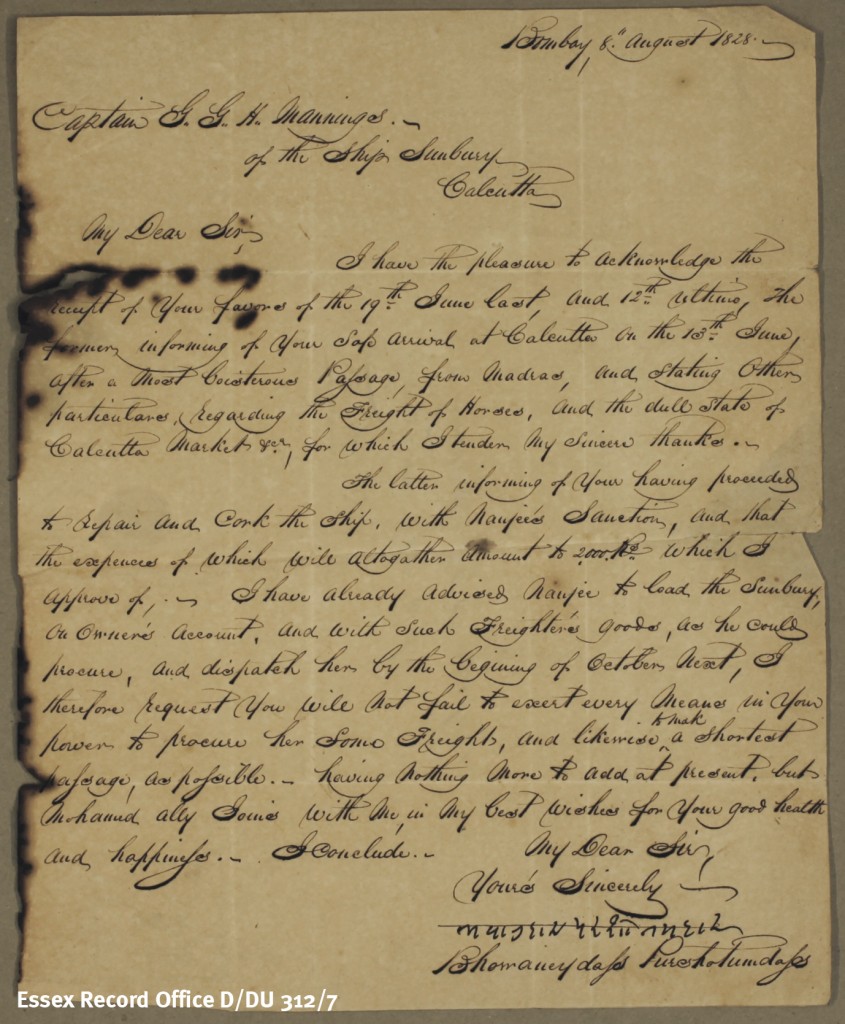

By the early 14th century the feudal system had been replaced by contracts between the king and an individual lord. These contracts or indentures of war were agreements whereby the king agreed to pay the lord a sum and in return the lord was bound to supply a fixed number of men.

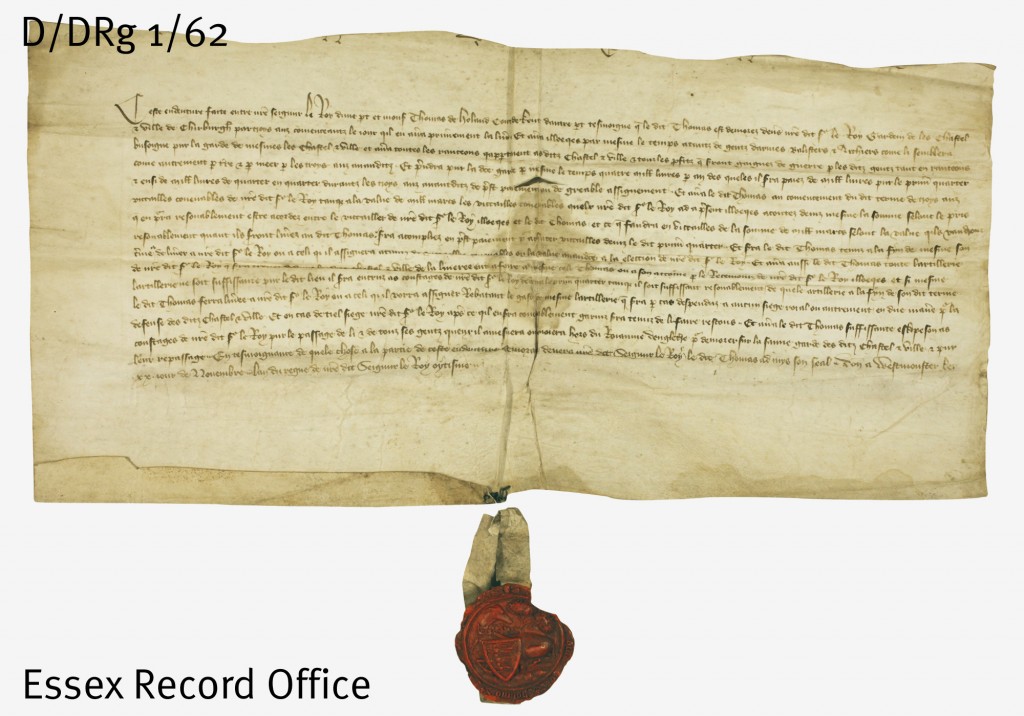

The agreement was written out twice on one piece of parchment and then divided with a wavy or indented line (hence the name) so that in the event of a dispute the two parts could be proved to have once been together. The king’s copies are held at the National Archives in the records of the Exchequer.

Two of the indentures which would have been given to the lord survive in the Essex Record Office. They are both written in Anglo-Norman French. In the medieval period Latin was the language of record, used in the courts and official and legal documents. However, French was the language of the king and his court until the 15th century and some documents including correspondence and agreements were written in French rather than Latin.

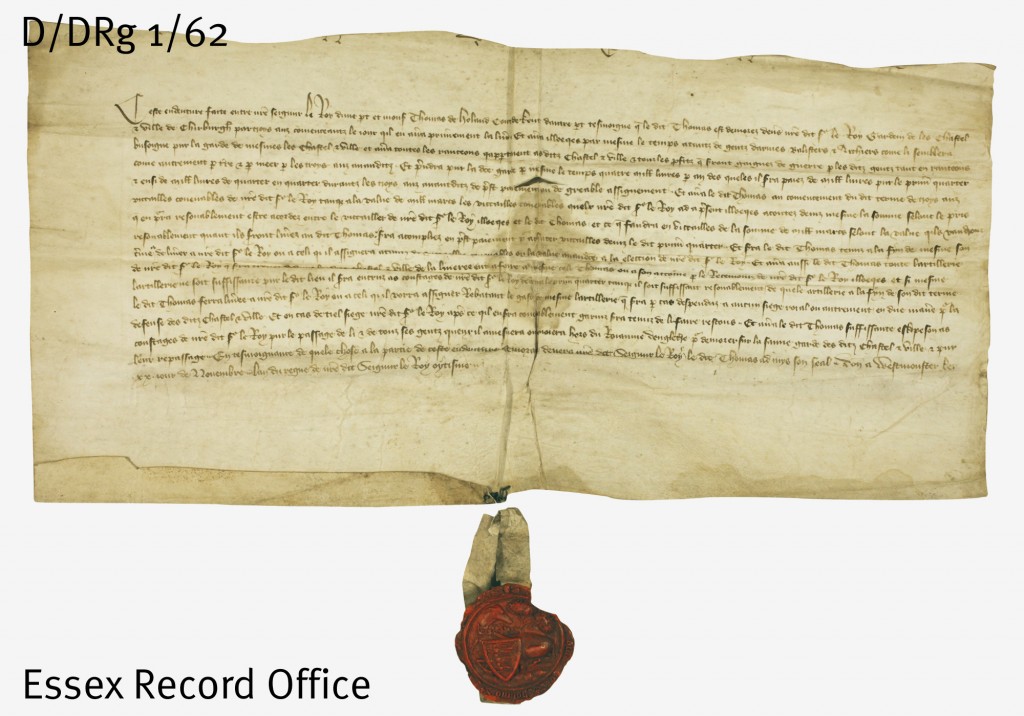

The earlier document dates from 1384 and is an agreement made between Richard II and his half-brother Thomas Holland, Earl of Kent (D/DRg 1/62). The earl was the governor of the castle and town of Cherbourg and was given £4,000 to provide a sufficient garrison and artillery to defend it. The earl’s seal shows a hind or white hart. Richard II also used the white hart as his personal badge. It is thought that it may have derived from the arms of Joan ‘The Fair Maid of Kent’, the mother of both Richard II and Thomas Holland.

Seal of Thomas Holland, Earl of Kent

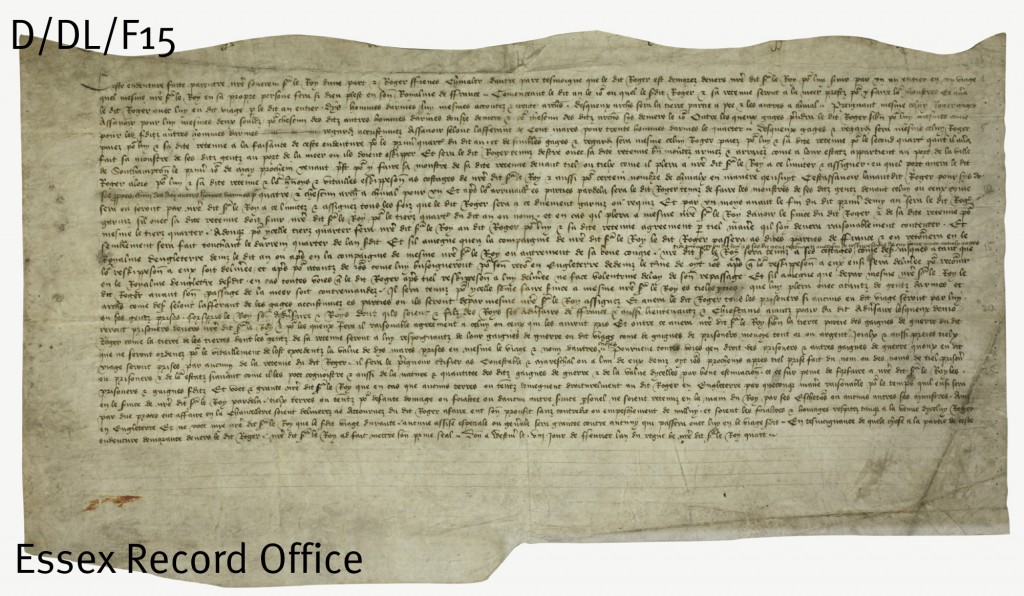

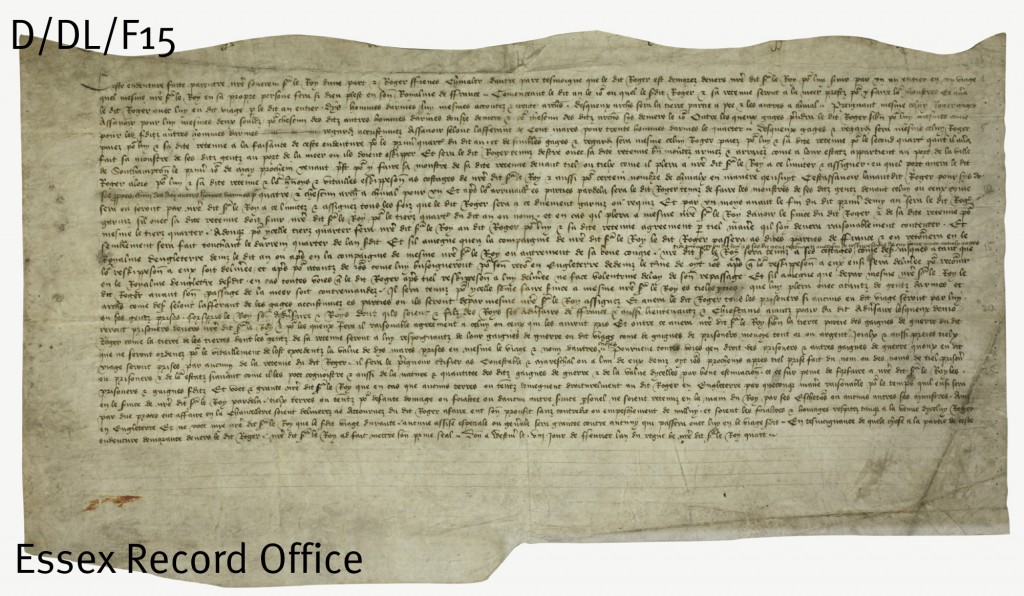

The second (D/DL F15) is dated 8 February 1417 and is an agreement for Henry V’s second campaign in France, following the siege of Harfleur and the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. This campaign was one of successful conquest resulting in the Treaty of Troyes which made Henry V heir to the French throne, and arranged his marriage to Catherine de Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France. It is an agreement made between the king and Sir Roger Fienes of Herstmonceux in Sussex. Sir Roger was to supply 10 men-at-arms and 30 archers, 20 of whom had to be mounted. The online medieval soldier database www.medievalsoldier.org lists the names of the men-at-arms archers in Sir Roger’s retinue.

‘War Charter’ between King Henry V and Sir Roger Fynes concerning an excursion into France, 1417. Includes detailed instructions regarding Sir Roger’s liabilities while on active service. It was this second campaign of Henry V which ended with the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. (D/DL F15)

The indenture specifies all the terms and conditions, including the daily wages to be paid – 2s. for Sir Roger, 12d. for the men-at-arms and 6d. for the archers. It also agreed further payment, depending on the length of the campaign, the division of prisoners (the ransoms would bring reward) and other prizes that might be gained from the campaign. Sir Roger was bound ‘to be with his said retinue well mounted armed and arrayed according to their estate at the port of the town of Southampton’ on 1 May 1417. It is likely that a knight such as Sir Roger would have had at least six different types of horses, including a war-horse for battle as well as pack-horses to carry his equipment, the men-at-arms four and the mounted archers one. They would then be shipped overseas at the expense of the king.

Waging war in this way was an expensive business. The need to finance the campaigns of the Hundred Years’ War meant that Edward III and his successors had to summon Parliament more frequently to grant taxes to pay for the war. The tax usually levied was called a fifteenth and tenth and was first introduced by King John and continued to the 17th century. This was levied on movable goods and was at the rate of one fifteenth for rural areas and one tenth for urban areas and royal land. In the 47th year of Edward III’s reign (1373-1374), William Reyne, one of the bailiffs of the borough of Colchester proposed a means by which the burden of the tax on the burgesses could be reduced. All men, both burgesses and ‘foreigners’ [forinceci] (from outside the town) would pay the tenth. In addition all ‘foreigners’ outside the borough who traded within the town would also be assessed to pay the tenth, instead of the rural rate of the fifteenth. This forced people of fairly modest means such as farmers, dealers and fishermen to pay at a higher rate than they might otherwise have expected. It was obviously successful as they chose to use the same method the following year.

In addition the king also had the right of purveyance, which derived from feudalism. This was the right to requisition goods and services for royal use, and was particularly used to feed and supply armies and garrisons. It was a system that was open to abuse by the royal officers and was unpopular. Both Edward III and Henry V used purveyance to equip their armies for France. Despite these taxes, the kings had to turn to moneylenders, including Italian bankers, for extra finance. In 1338 wool was shipped from Harwich to pay the Bardi (Florentine) financiers who had lent the king money.

To find out more about the Battle of Agincourt from expert speakers, join us on 31 October 2015 for Essex at Agincourt; all the details of the day are here.