As The Great British Bake Off continues on BBC2, we bring you the second in our special series exploring some of the recipe books in our collections.

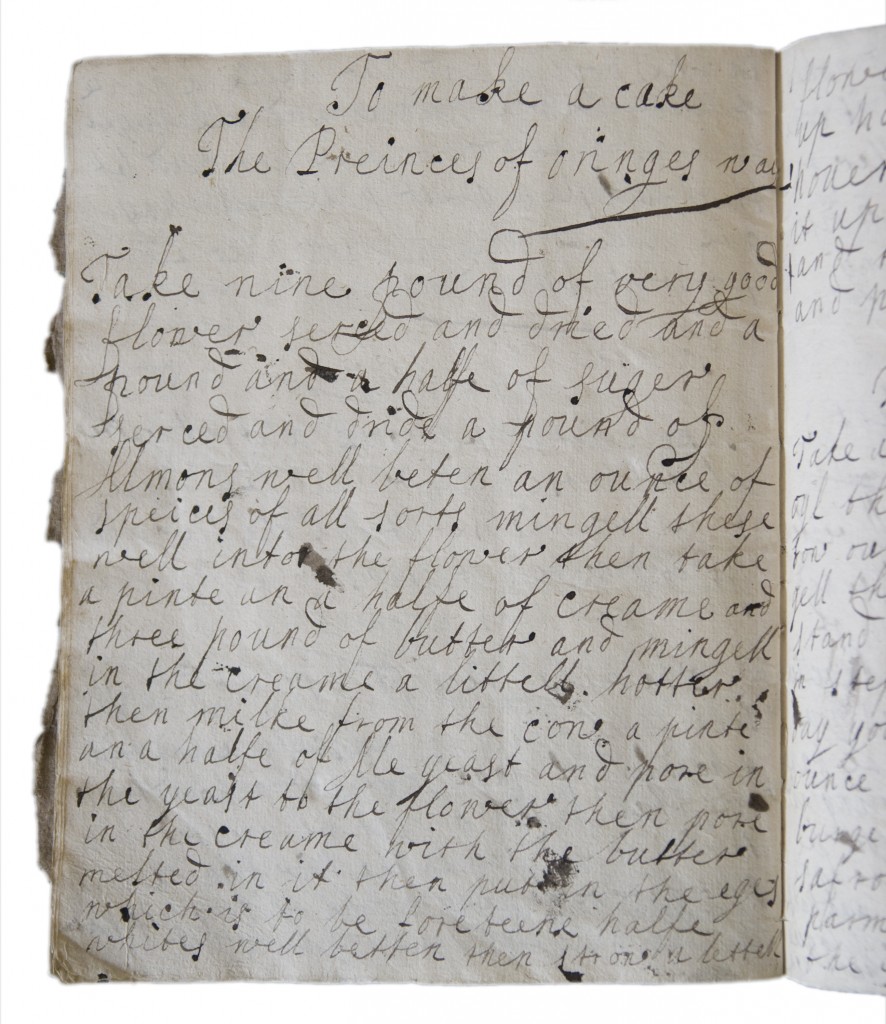

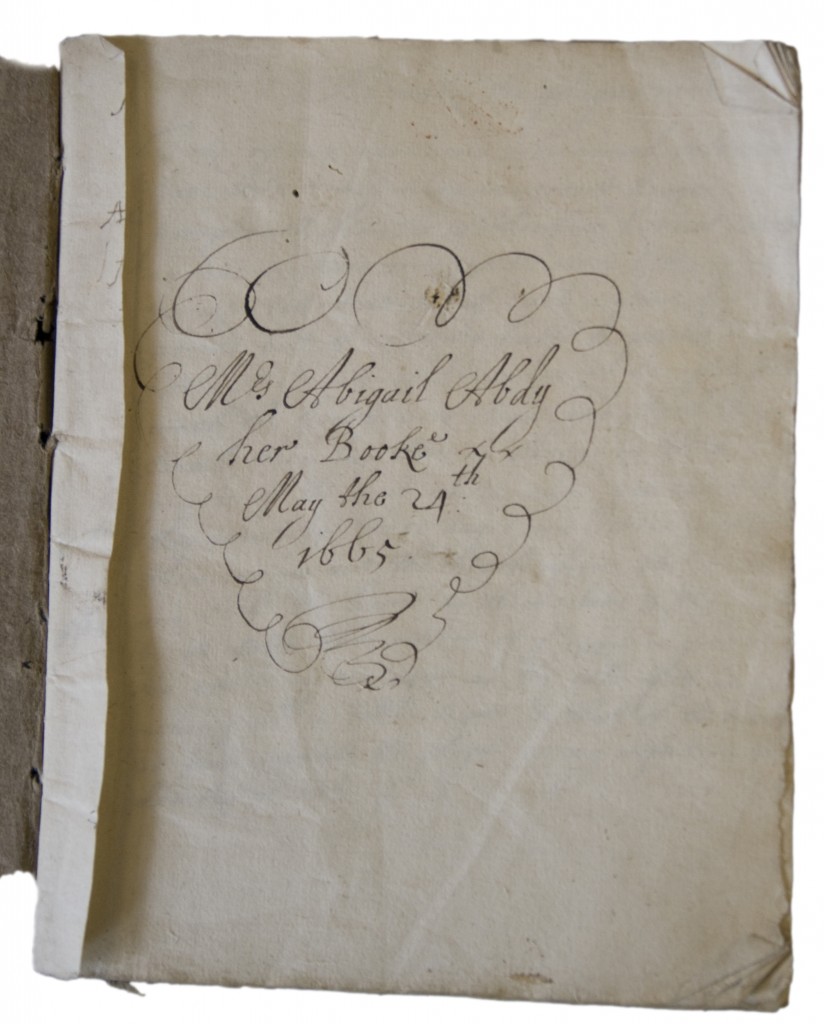

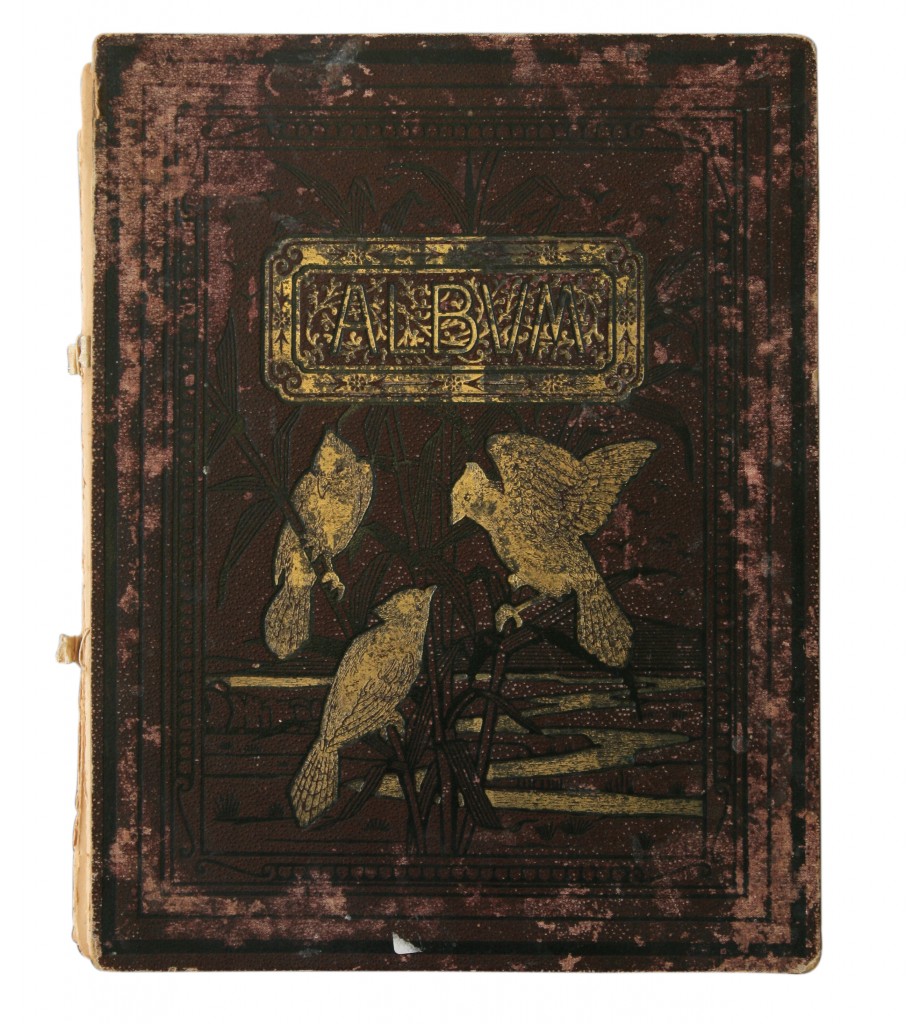

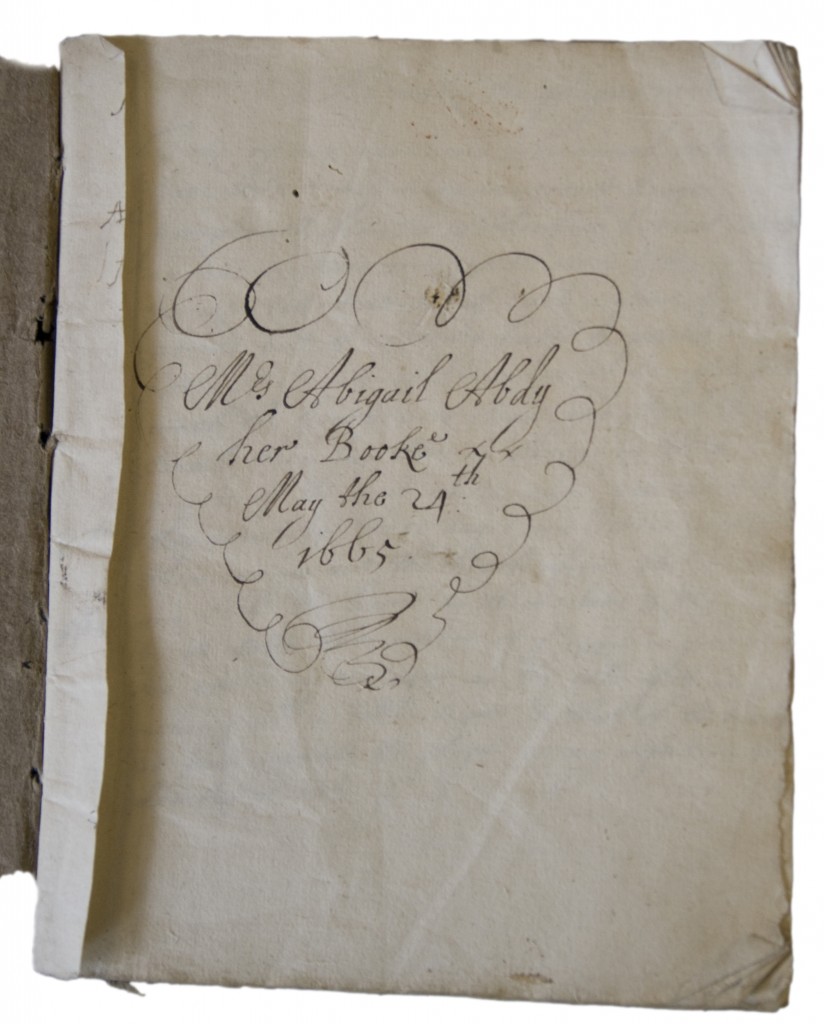

Today we look at another of our very earliest recipe books, written by Abigail Abdy, beginning in 1665 (D/DU 161/623).

Title page of Abigail Abdy’s book – reading ‘Mrs Abigail Abdy her book May the 24th 1665’

Abigail was born in 1644, the daughter of Sir Thomas Abdy of Felix Hall, Kelvedon, a lawyer and landowner. Sometime after 1670 she married Sir Mark Guyon, son of Sir Thomas Guyon, a rich clothier, becoming his second wife.

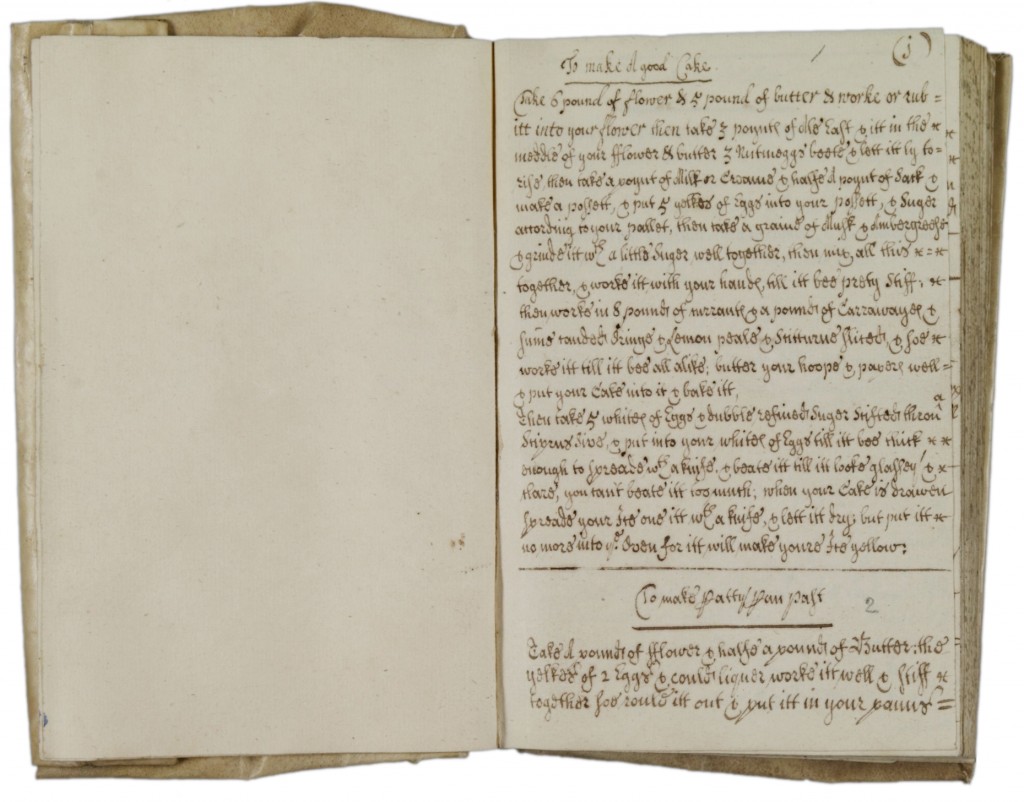

Much of the book is taken up with medical concoctions, for both humans and animals, such as ‘A very good Drink for ye Rickitts’, ‘A good Receipt for sore eyes, when one has the smallpox’, ‘To make the plague water’, ‘To make cordiall water, good against any infection, as the plague, small pox &c.’, and ‘A very good drinke for a Bullock’.

Given that the book was begun in 1665, during the Great Plague in London, it is not surprising that the recipes concentrate on warding off and treating infection.

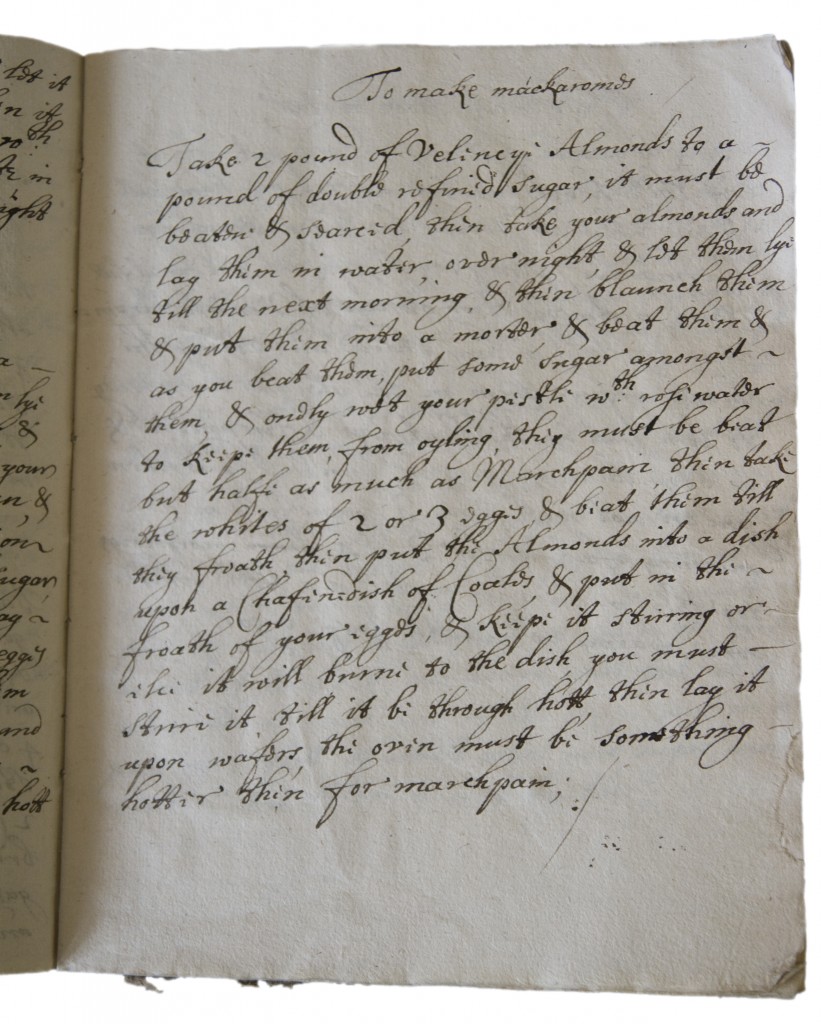

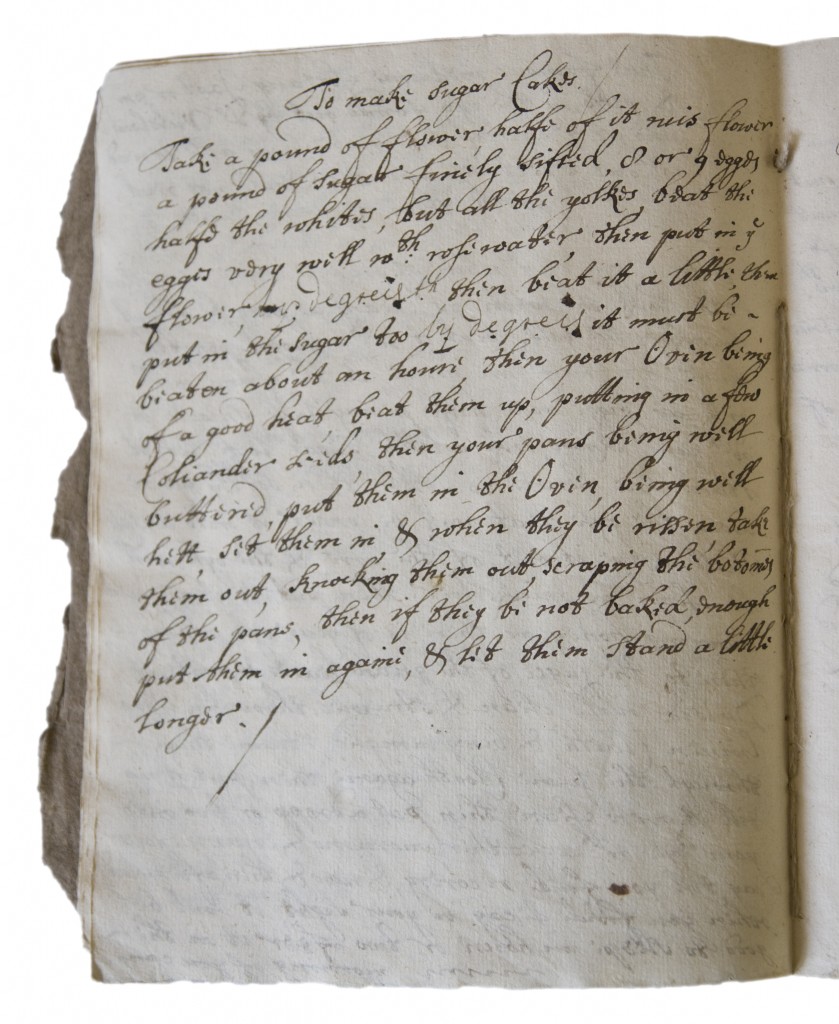

Alongside these mixtures are recipes much more recognisable to modern eyes, such as these for macaroons and sugar cake:

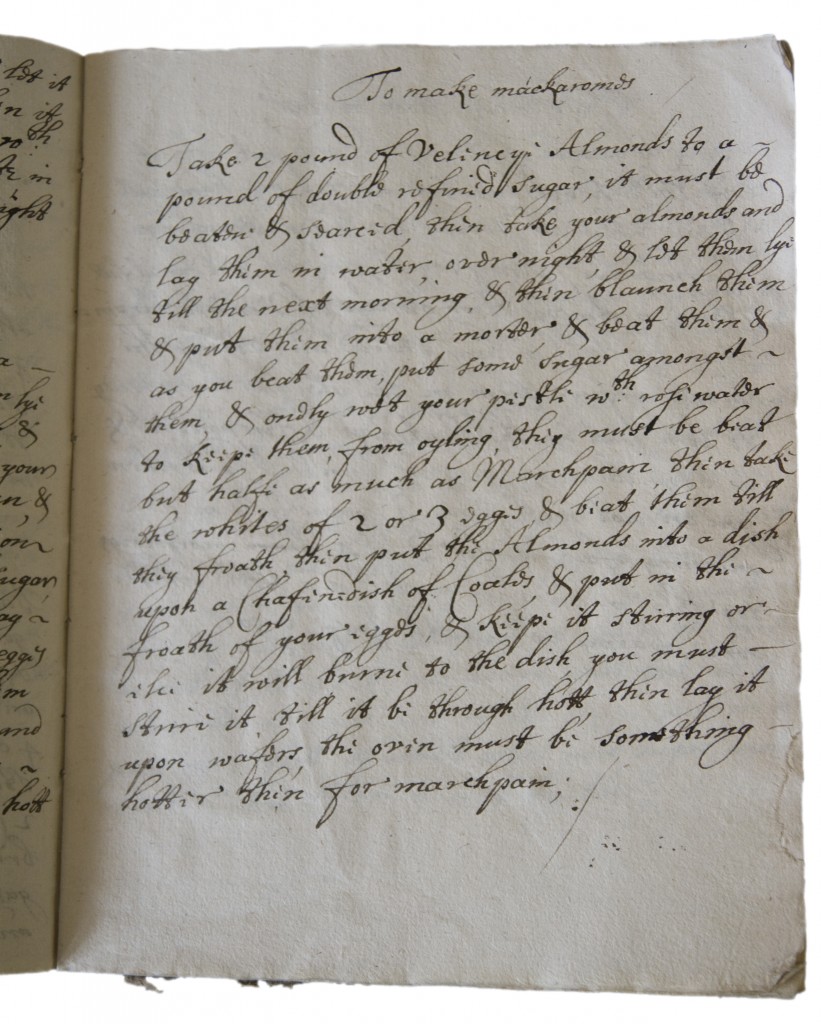

Abigail Adby’s recipe for macaroons

To make mackaromes

Take 2 pound of Veliney Almonds to a pound of double refined sugar, it must be beaten & searced [sifted] then take your almonds and lay them in water, overnight, & let them lye till the next morning, & then blaunch [blanch] them & put them into a mortar, & beat them & as you beat them, put some sugar amongst them, & onely wet your pestle with rose water to keepe them, from oyling, this must be beat but half as much as Marchpain then take the whites of 2 or 3 eggs and beat them till they froath, then put the Almonds into a dish upon a Chafinedish [chafing dish] of Coales & put in the froath of your eggs, & keepe it stirring or else it will burne to the dish you must stirre it till it be through hott then lay it upon wafers the ovin must be something hotter than for marchpain.

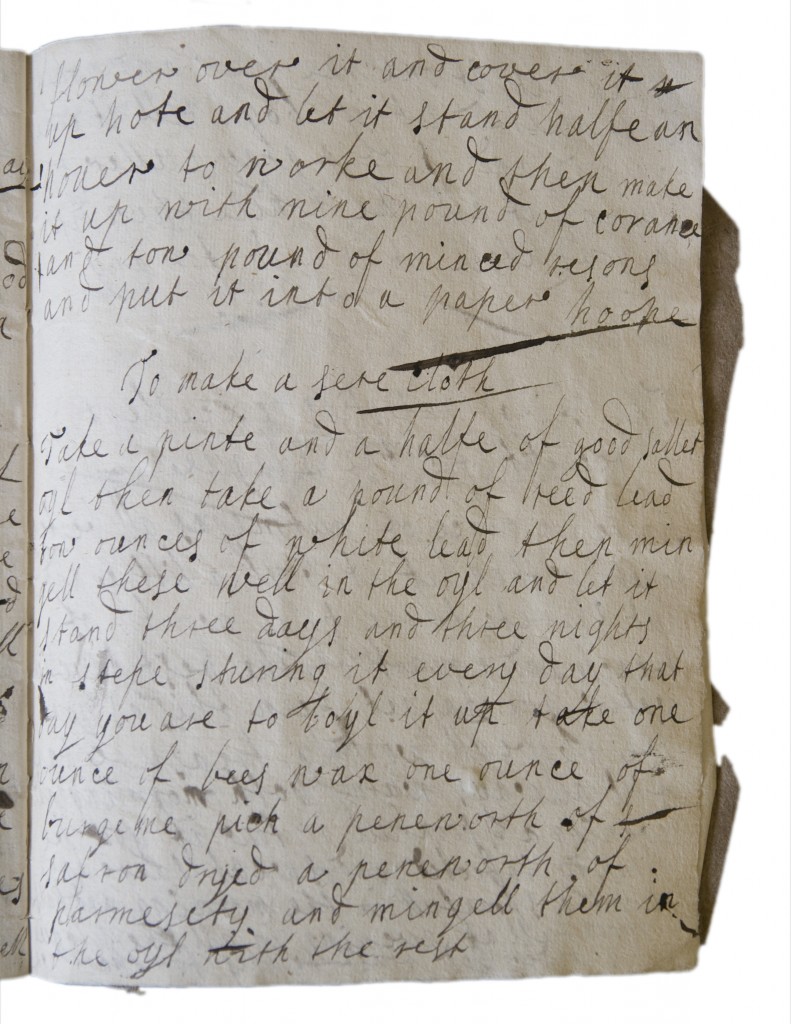

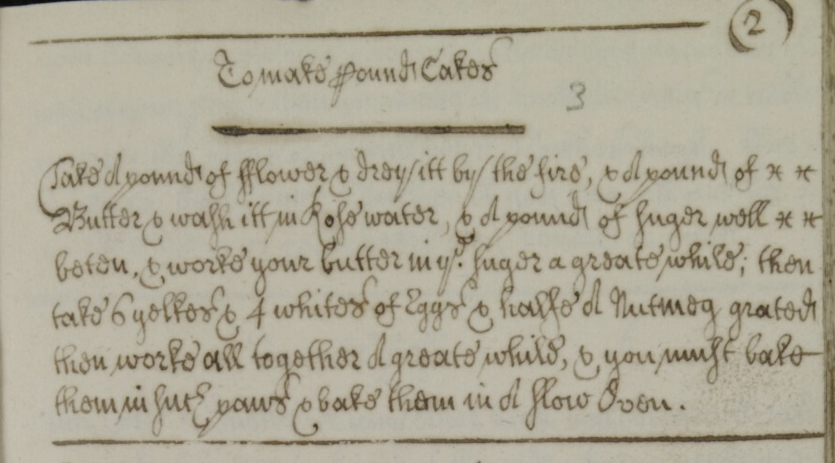

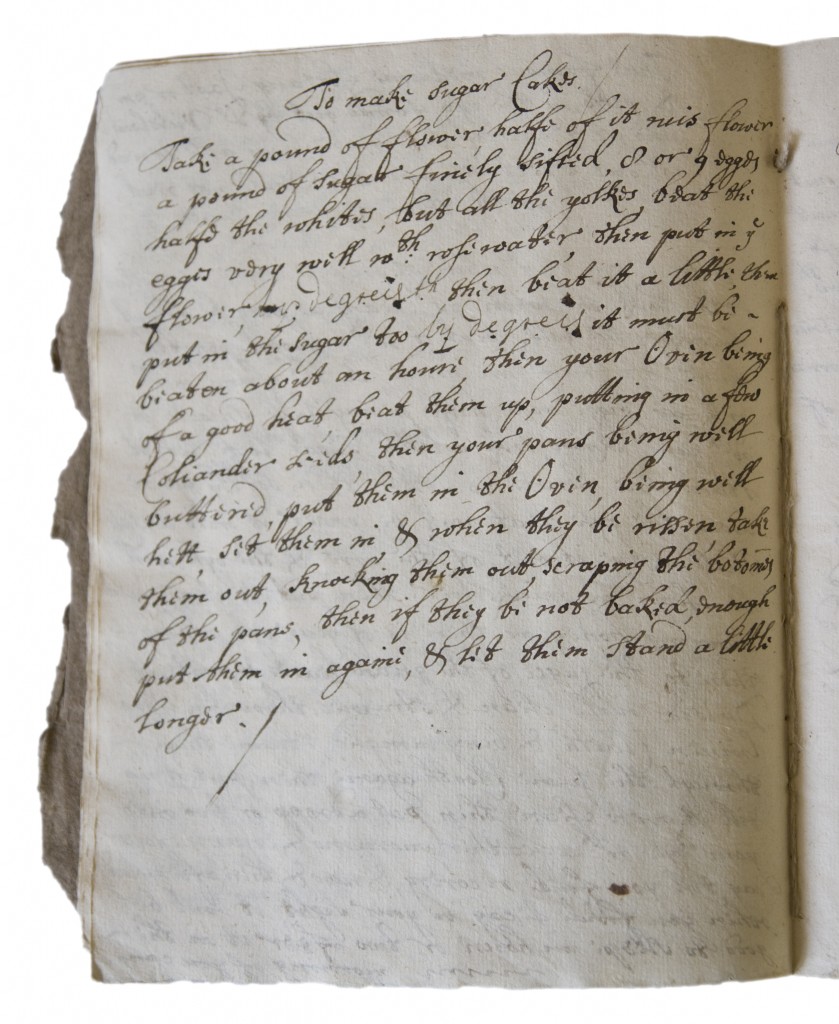

Abigail Adby’s recipe for sugar cake – including the instruction to beat the mixture for an hour!

To make sugar Cakes

Take a pound of flower, halfe of it [rice] flower a pound of sugar finely sifted, 8 or 9 eggs halfe the whites, but all the yolkes, beat the eggs very well with rose water, then put in ye [the] flower, by degrees then beat it a little, then put in the sugar too by degrees it must be beaten about an houre then your Ovin bring of a good heat, beat them up, putting in a few Coliander seeds, then your pans being well buttered, put them in the Oven, being well hett, set them & when they be rissen take them out, knocking them out, scraping the botomes of the pans, then if they be not baked enough put them in againe, & let them stand a little longer.

Abigail died in 1679, aged just 35. Joseph Bufton, the Coggeshall diarist, records that she was buried quickly, late in the evening by torches, without a sermon, suggesting that she had died of an infectious illness, possibly the plague. This was not, however, the end for Abigail’s book – find out more in our next post, coming soon!

If you’re visiting the Record Office soon, look out for our display of recipe books in Reception, or pop up to the Searchroom to order Abigail’s book (D/DU 161/623), or Miss A.D. Harrison’s article about it (D/DU 161/661).