2015 marks the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, Henry V’s famous victory against the French on 25 October 1415. To mark this milestone, we are hosting Essex at Agincourt, a one-day conference on Saturday 31 October 2015 looking at the contribution made by our county to Henry’s campaign. This is a joint event with the Essex branch of the Historical Association, and all the details can be found here.

In this blog post, ERO’s medieval specialist Katharine Schofield takes a broader look at the context of the Hundred Years’ War and the part that Essex played in some of its campaigns. Read on for a quick crash course in this century-spanning medieval conflict.

What was the Hundred Years’ War?

The Hundred Years’ War lasted from 1337 to 1453 (116 years). Instead of a continuous war, it was a series of campaigns and battles, sometimes interrupted by periods of peace, between England and France for control over the French kingdom. Apart from the main English campaigns, smaller forces were sometimes sent to support English allies in France.

The Battle of Agincourt, from Chroniques d’Enguerrand de Monstrelet (early 15th century) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

After gaining control of his kingdom from his mother and her reputed lover Roger Mortimer in 1330, Edward III initially waged war against Scotland. Philip VI of France supported his allies the Scots against the English, threatening the remaining English lands in Gascony (the area to the south and east of Bordeaux). This interference was one of the reasons which led Edward III to claim the French throne for himself. In 1340 Edward III began to call himself king of England and France, a title held by every successor until it was abandoned by George III in 1800. He also added the French arms of the fleur-de-lys to the royal arms.

![Edward III described as King of England, Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine in the Maldon Borough charter of 1330 (Eduardus dei Gra[cia[ Rex Angl[orum] Dommus Hibernie Duc Aquit[ane]) (D/B 3/13/3)](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/D-B-3-13-3-extract-1024x680.jpg)

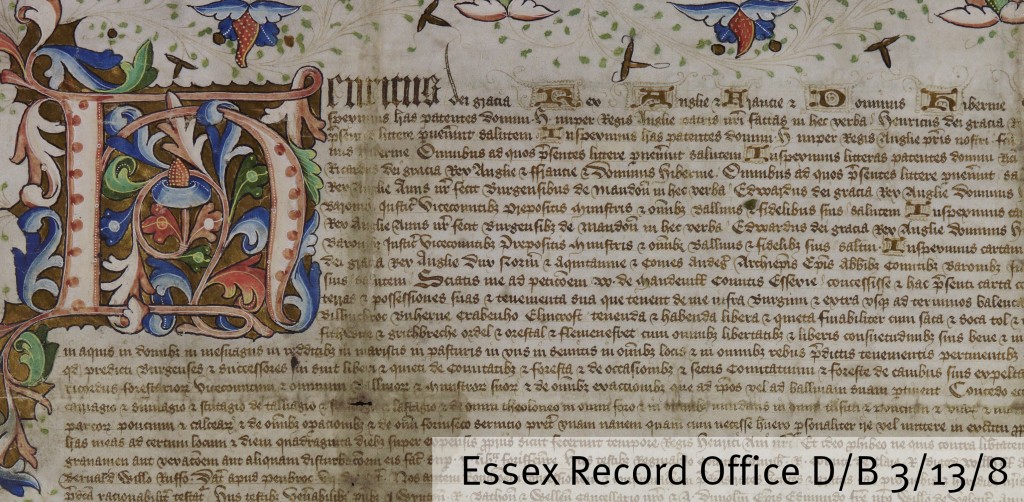

Edward III described as King of England, Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine in the top line of the Maldon Borough charter of 1330 (Eduardus dei Gra[cia[ Rex Angl[ie] Dominus Hibernie Duc Aquit[ane]) (D/B 3/13/3)

Henry VI described as King of England and France and Lord of Ireland on the Maldon Borough charter of 1454 (Henricus dei gracie Rex Anglie France Dominus Hibernie) (D/B 3/13/8)

The Battle of Sluys

The first English victory of the war was the naval Battle of Sluys on 22 June 1340 which led to the almost complete destruction of the French fleet and resulted in English control over the Channel, removing the threat of invasion. Edward III sailed to the battle on La Cogge Thomas from Harwich, with 200 ships. A further eleven ships were left behind under the command of the town’s bailiff, John But, to act as reinforcements.

Essex and the supply chain

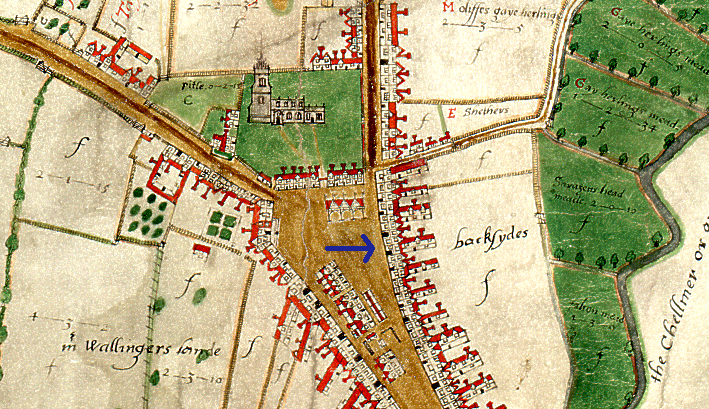

The start of the Hundred Years’ War brought importance and prosperity to the port of Harwich. The town had only been established by the Bigod family in their manor of Dovercourt in the mid-13th century. Edward III used it as an important base in his war against the French. In 1338 he granted murage (the right to build walls) to the town. It was at Harwich that Edward III first sent out letters signing himself King of France in 1340. In 1347 the town supplied 14 ships and 283 seamen for the Siege of Calais in 1347.

The records of the Exchequer at the National Archives record the expenses of the sheriff of Essex, William de Wauton in 1340 for the ‘divers provisions for the use of the King for his passage beyond the seas’. All the Essex hundreds had to send material and food to Maldon or Manningtree, from where they were shipped to Harwich.

Goods such as canvas supplied from London and rope bought in Suffolk , together with money for wages sent from London were all transported to Harwich. The accounts record that Essex supplied four gangways (pontes) 30 feet long and 5 feet wide. The county also provided stabling for the horses on the ships, with 418 hurdles 9 feet long and 6 feet wide ‘roughened and close woven’ to prevent the chargers’ hooves penetrating and 116 long racks, 24 feet long.

Places throughout the county supplied goods – hurdles came from Purleigh, Totham, Terling and Hatfield Peverel, racks from Heybridge and 864 boards arrived from (among other places) Broomfield, Feering, Messing, Coggeshall and Colchester.

In the 1340s the English and French were involved in a war in Brittany over the succession to the duchy, each supporting a different side and ally in the conflict. In 1342 the sheriff of Essex was required to supply 1,098 sheaves of arrows and 1,000 bowstrings which were sent to the Tower. In that same year 10 ships from Harwich, five from Colchester, four from Brightlingsea and three from Maldon formed part of a fleet to take the English commander Sir Walter de Manny to Brittany.

In July 1346 Edward led a land campaign against the French. Essex again played its part in the campaign. The county sent 200 archers, 160 bows and 400 sheaves of arrows and the county’s towns were required to supply armed foot-soldiers, 20 from Colchester (later retained for the town’s defence), 6 from Saffron Walden and 4 each from Chelmsford, Braintree and Waltham Holy Cross. At the beginning of the year the sheriff had been required to supply another 1,000 hurdles, 24 gangways, 2,000 boards and 200 empty tuns for water.

The Battle of Crécy

On 26 August 1346 the English archers demonstrated the power of the longbow winning the decisive Battle of Crécy. In October Essex was required to supply another 30 archers and in February 1347 an additional 200. After Crécy the English forces went on to besiege Calais, which after a year surrendered in 1347. It was to remain in English hands until 1558.

The Plague

Following these victories, Europe was devastated by the Black Death. The bubonic plague moved across the continent, killing an estimated third of the population of England alone.

The Black Prince

It was not until 1356 that Edward’s eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales (the Black Prince) led the next major campaign in France, this time not in the north, but closer to the English lands of Aquitaine. The second major English victory, again with the aid of the longbow, came at the Battle of Poitiers on 13 September 1356. Among the French prisoners captured was John II, King of France. Edward III’s final invasion of France followed the battle but John II’s son, the future Charles V, forced the king to negotiate the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360 which allowed the return of John II to France in return for hostages and a ransom of 3 million crowns.

Richard II, Henry IV

Edward III died in 1377 and he was succeeded by his ten year old grandson Richard II, the son of the Black Prince who had died in 1376. In 1380 Charles V of France died and was succeeded by his eleven year old son Charles VI (the Mad). There were no further land campaigns by the English in France until Henry V succeeded his father Henry IV in 1413.

Henry V

Henry V reasserted his hereditary claims in France and in August 1415 sailed from England to besiege the town of Harfleur. Following the town’s surrender Henry V’s army met a much larger French force at the Battle of Agincourt on 25 October 1415. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the longbow was again of great importance in the victory of the English forces. Civil war followed in France and when Henry returned for another campaign in 1417 he was able to force concessions on the French. In 1420 the Treaty of Troyes recognised him as the regent of France and heir to Charles VI and in that same year he married Charles’ daughter Catherine de Valois.

Marriage of Henry V of England to Catherine of Valois British Library, Miniature of the marriage of Henry V and Catharine de Valois: Jean Chartier, Chronique de Charles VII, France (Calais), 1490, and England, before 1494, Royal 20 E. vi, f. 9v,

Henry VI

In 1422 Henry V died leaving a nine month old son Henry VI. A month after his father’s death he became king of France when Charles VI died and was crowned king of France in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in 1431.

Henry V left his younger brother John, Duke of Bedford as his regent in France. The English victory at the Battle of Verneuil on 17 August 1424 again saw the pre-eminence of English archers as a weapon of war and marked the end of the great English successes in France.

In 1428 the English laid siege to Orléans but the French were successful in their resistance, inspired by Joan of Arc and went on to defeat the English elsewhere. Joan of Arc was captured in 1430 and burned at the stake in 1431. However, this failed to improve the fortunes of the English army, who continued to suffer defeats.

Coastal raids on Essex

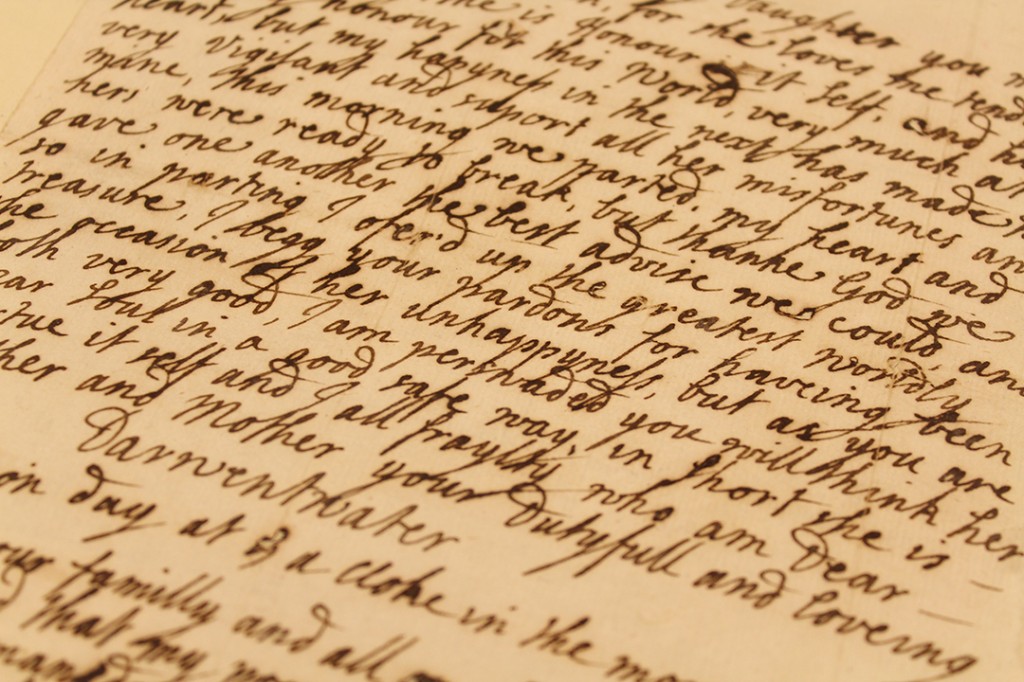

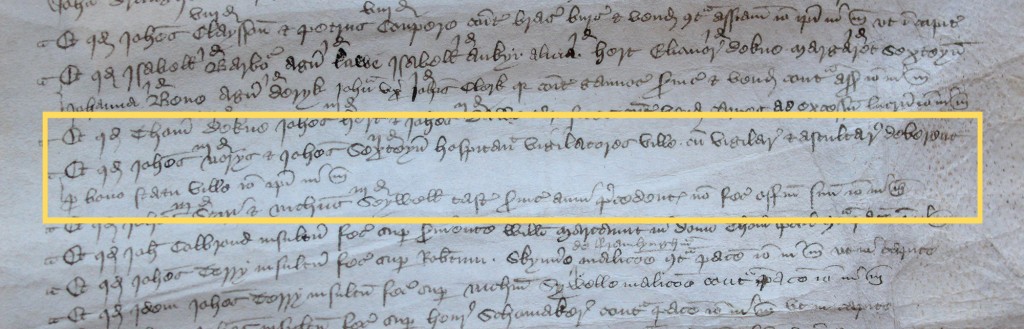

In between the major land campaigns, there were minor skirmishes and raids on the coastal towns of each country. In 1451 the Harwich court roll records a raid by the French in which nine people were killed. John Sexteyn, John Hervy, Peter Coylour and Richard Smyth were charged at the borough court that having sworn to watch the town of Harwich [villam derwych] faithfully during the night, the town was spoiled and destroyed. The court promised further enquiry into this matter.

![The jurors present that John Sexteyn, John Hervy, Peter Coylour and Richard Smyth were charged and sworn to watch the town of Harwich [villam derwych] faithfully during the night when it happened that the town was spoiled and destroyed [expoliairi et destrui] by our enemies and our neighbours to the number of nine were slaughtered; whether in this default or not at present they do not know’; therefore they have to inquire and make their verdict at the next court (St. Barnabas 29 Henry VI 1451)](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IMG_8032-edit-1024x244.jpg)

The jurors present that John Sexteyn, John Hervy, Peter Coylour and Richard Smyth were charged and sworn to watch the town of Harwich [villam derwych] faithfully during the night when it happened that the town was spoiled and destroyed [expoliairi et destrui] by our enemies and our neighbours to the number of nine were slaughtered; whether in this default or not at present they do not know’; therefore they have to inquire and make their verdict at the next court (St. Barnabas 29 Henry VI 1451)

John Norys and John Sexteyn amerced 3d. each for entertaining [hospitare] the watchment [vigilatores] of the town when they ought to be watching and ? [? Guarding] for the good of the town (St. Barnabas 28 Henry VI 1450).

![Adam Palmere showed to our French enemies [inimici nostris franc] the very secret way of our port of Orwell leading their ships in safety to the grave damage of the town and against the ordinance and statute of England (St. Barnabas 34 Henry VI [1456])](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IMG_8040-edit-1024x265.jpg)

Adam Palmere showed to our French enemies [inimici nostris franc] the very secret way of our port of Orwell leading their ships in safety to the grave damage of the town and against the ordinance and statute of England (St. Barnabas 34 Henry VI [1456])

The Battle of Castillon on 17 July 1453 is generally held to be the end of the war. By the 1450s English attention moved away from France to civil war in England (the Wars of the Roses) between the Lancastrians represented by Henry VI’s supporters and the rival claim of the house of York.

Essex men who took part

As well as the money and goods contributed to the military campaigns of the Hundred Years’ War, Essex also supplied men to fight in the armies that went to France. In addition to the sailors from Harwich, Colchester and Maldon, men from the county would have fought in the retinues of the knights and lords who took part in overseas expeditions.

John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford fought at the Battles of Crécy and Poitiers and at the siege of Calais. He died in France while on campaign in 1360. His grandson Richard de Vere, 11th Earl of Oxford was one of the commanders at the Battle of Agincourt.

William de Bohun, 6th Earl of Hereford, 5th Earl of Essex and 1st Earl of Northampton held the lands in the county originally held by the de Mandeville family, mostly in the north and west of the county. He fought at Sluys, Crécy and Calais and was buried at (Saffron) Walden Abbey in 1360.

Robert, 1st Lord Bourchier fought in Brittany and at Crécy and was buried in Halstead church. The Bourchiers were lords of the manors of Abels and Stanstead Hall in Halstead and later Prayers in Sible Hedingham and Little Easton. They inherited the manor of Little Easton through marriage from Sir John de Lovayne who was killed at the siege of Calais. Robert Bourchier’s eldest son John, his grandson William, Count of Eu and his great-grandson Henry, Earl of Essex all fought in campaigns in France, William at Agincourt.

John de Coggeshall was among those killed at the siege of Calais, having fought at Crécy. He was the eldest son of Sir John de Coggeshall, lord of a number of manors including Little Coggeshall and sheriff of Essex for a number of years.

Other Essex men killed in the siege of Calais included Sir William de Wauton, who fought in the retinue of the earl of Oxford and was buried at Tilty Abbey and Sir Robert de Lacy, lord of the manor of Newnham Hall in Ashdon.

Knights and landed families of the county were represented in the retinues of the great landowners. John, son of Henry Helyoun of [Helions] Bumpstead was in the retinue of the Black Prince in 1346. Sir Baldwin de Botetourt was master of the Black Prince’s horses and a member of his bodyguard at Poitiers. He was rewarded by the grant of the Crown’s manor of Newport in return for a rose rent. Sir Richard Waldegrave whose family held the manor of Wormingford fought in the retinue of earl Humphrey de Bohun in the early 1370s.

________________________________________________________________________

Essex at Agincourt

A joint event with the Essex branch of the Historical Association to mark the 600thanniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, Henry V’s famous 1415 victory against the French. Join us for talks from Professor Anne Curry, internationally-renowned expert on the Hundred Years War, Dr James Ross, an expert on the medieval nobility of East Anglia, and the English Warbow Society.

Saturday 31 October, 11.00am for 11.30am-3.30pm

Advance booking essential

Tickets: £15 for non-HA members; £7 for HA members, including refreshments and lunch

Non-HA members: please book through the ERO on 033301 32500

HA members: please book through the Essex branch of the Historical Association on clem.moir@btinternet.com or 01245 440007

Part of the Chelmsford Ideas Festival