As the centenary of the end of the First World War approaches, we are delving into our collection looking at some of the fascinating wartime records we look after. Join us on Saturday 10th November 2018 to mark 100 years since the Armistice at ‘Is this really the last night?’ Remembering the end of the First World War.

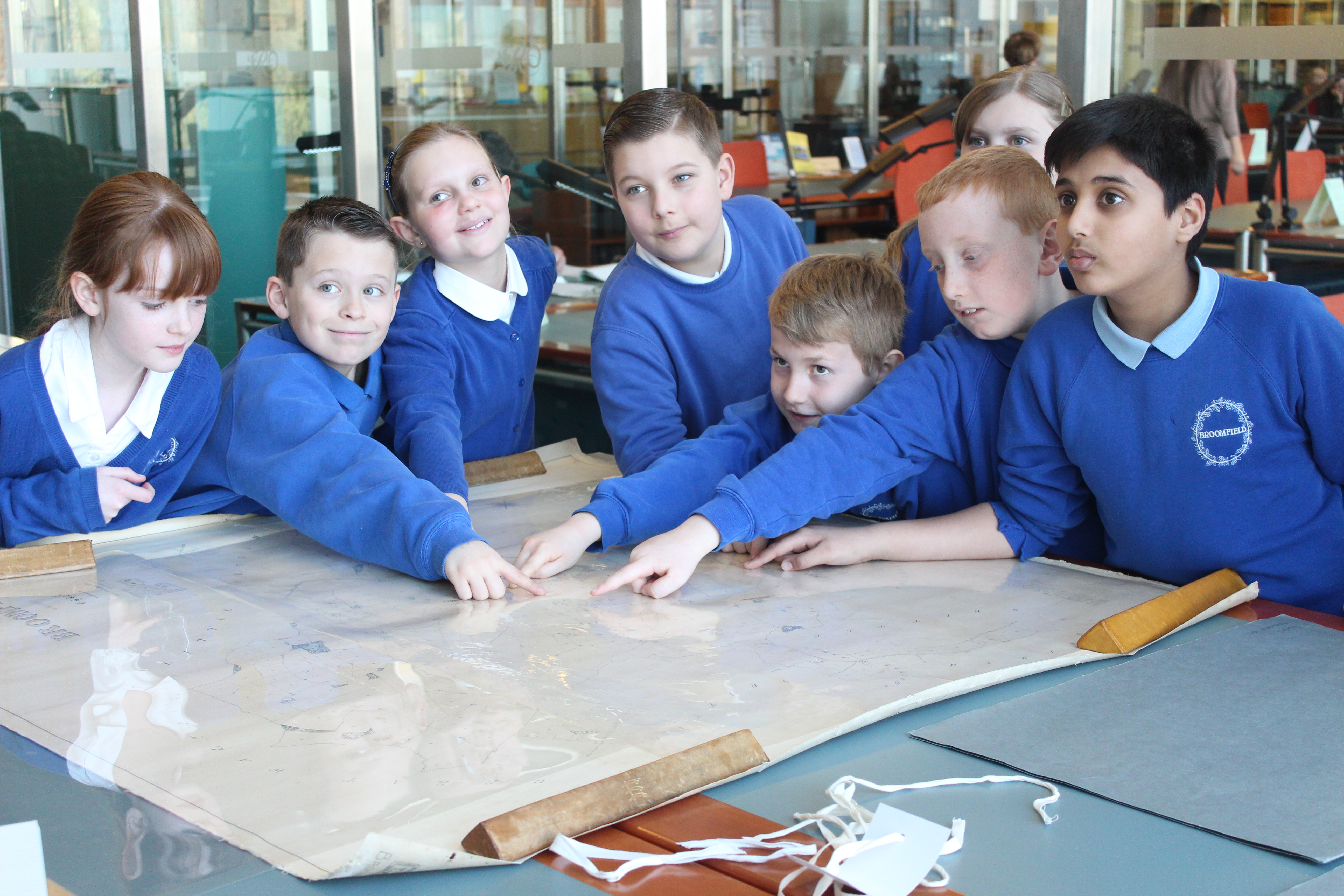

In 1992 Dilys Evans’s year four class in Hockley was learning about the First World War. When Dilys mentioned this to her neighbour, a veteran of the First World War, he immediately offered to come and speak to her class about his experiences. Fortunately for us, she recorded this meeting of generations and later deposited the tape at ERO (catalogued as SA 24/1011/1).

The veteran in question was Alf Webb, who at the time was aged 95. He volunteered for the army in 1914 aged 17, only realising the horror he had let himself in for when he arrived in France.

The whole recording is about 45 minutes long, and in it the children ask Alf questions about his wartime experiences. Alf talks about his recollections of both the mundane detail and the harsh reality of war, in a matter-of-fact and unflinching way (perhaps surprising given the audience). He talks about mud and lice, tactics and trenches, the death of friends and colleagues, and his own attitude to the war, which was to ‘try and survive and get out of this’.

Extracts of the recording are available on our SoundCloud channel (you can listen by clicking the player above), and we will shortly be publishing the whole recording online. In the meantime, you will be able to hear it at our event marking 100 years since the Armistice, ‘Is this really the last night’? Remembering the end of the First World War, on Saturday 10th November.

Alf Webb was born in Hackney in 1897. His parents were Christopher, a boot finisher, and Mary. Alf had an older sister, Rosetta, and a younger brother, Alexander, who also served in the army towards the end of the war.

Alf began his military service in the cavalry, but ended up in the Machine Gun Corps. He answers the children’s questions frankly, and clearly wanted to convey the horrors of war to them.

One of the questions put to Alf by the children was ‘Did you think the war was going to be exciting?’. He replied:

‘I did when I first joined, I thought it would be wonderful. I’d be in the cavalry you see with spurs on and riding breeches and a posh bandolier out there, I didn’t realise we was going to get blown to bits. But, when you’re young, you see there hadn’t been a war before, only the Boer War which was all open country, and so we had nothing to go on, and to a young person, I mean I was 17, I was 18 by the time I’d gone over the top, it seemed a very exciting thing, but my God, you soon alter your opinion.’

He tells the children several times how fearful he felt being at the front:

‘When you hear people saying they’ve got no fear I don’t believe them because the first time I ever went in the trenches I was frightened out of me life. There had been a bombardment and there were so many dead bodies and things lying about I was sick I was scared, and the Sergeant said to me ‘all right boy, in a few months you’ll be used to it’ and after about 3 months you are.’

British machine gun crew (Imperial War Museums)

Describing one occasion when he was firing a machine gun, he told them that in half an hour he had three different men come up to work the gun with him and each get killed in turn:

‘all you do is to push them out the way and another one comes up and takes their place. In some ways it doesn’t seem much because all you see is them fall down, fall over, but it’s very very nasty when you see the chap next to you is feeding these in and a shell or something or a burst hits him in the face and you look round and you see your mate there with no face. And there’s blood all over you. It’s not very nice, you don’t enjoy it.’

When asked by one of the class ‘How many Germans do you think you shot?’, he replied: ‘I’d have to say thousands, because with a machine gun going at 600 shots a minute … you could just see them dropping.’ Another child asked ‘How many times did you make a friend and then have to watch them die?’. Alf’s answer was: ‘Oh dozens of times. It happens all the time. There’s no way out of it.’

On the subject of how long he felt at the time the war would last, Alf told the class:

‘Well it seemed to us it was going to go on forever. There seemed to be no end to it because when things were static right from 1915 on advances used to be a matter of just a few yards and that sort of thing.’

The war did, of course, finally come to an end, and one of the children asked Alf how he felt at that time:

‘Highly elated. Actually, I’ll go onto that now. We were pushing the Germans back in 1918. After they broke through, we stopped them and then we were pushing them back. And I happened to get to a place called Verviers in north Belgium, and Spa, where the Armistice was signed was a few kilometres away up in the mountains so we was actually the first to know that an Armistice had been proclaimed. And in Verviers where we were, the villagers there opened their estaminets, like our pubs or anything, and everything was open for everybody. The troops were lighting and other people there were lighting tar barrels so we could have light, and well, there was general rejoicing, although we knew that we were still in trouble as you might say, there was no more fighting to be done. But Spa itself was a beautiful part of Belgium, it’s very hilly there. In fact they hadn’t had much trouble there before and they’d still got trams running. But the trouble was they’d got so little power that if you got on one of these trams … to go uphill you all got out and pushed it up the hill.’

The children were also interested in Alf’s love life, asking if he had a girlfriend during the war. ‘Yes,’ he replied; ‘And I’m still married to her!’ Further detail followed:

‘Actually, before the war, I was with a lot of other youngsters, we used to belong to the boys club, and there was one lot of girls that was four sisters, and the one that I married was one of them, I’d been out with all of them! We used to enjoy life, we was all friends together… We still corresponded afterwards and eventually when I came home we got married. That was in 1924 we got married, and she’s still alive today thank goodness.’

The children clearly had an understanding of the effect wartime experiences had on the mental health of many of the people who experienced it, and one child asked Alf ‘Did you dream about the war?’. He answered:

‘For the first twelve months after I was demobilised, I was quite OK. And then I used to wake up in the night and I could see all of it over again, I could see my friends being killed and dying. It was so bad that I couldn’t even go to work. I saw our local doctor, old Dr Anderson, he said ‘Look, I’ll tell you the best thing to do, you don’t want medicines, you don’t want anything like that, get away to a quiet place in the country, anywhere, where you can go out into the open air. Eat when you’re hungry, sleep when you’re tired. Don’t try and not think about anything, just try and enjoy it’. And that’s what I did. Actually, it might seem strange to you, but we was in London, and I went down to Battlesbridge, which is not far from here. My mother and father knew an elderly couple who were retired and bought some cottages down there, and I went down there and stopped there for three weeks. I used to get up in the morning, and there was big fields between there and the river Crouch, and I used to walk all round those, go in the Crouch swimming and that sort of thing, and at the end of three weeks, it was all gone. I don’t know if I was lucky or what it was, but that’s how it went. For the first twelve months out I didn’t feel, everything didn’t matter, and then as I say I got this reaction. And I couldn’t sleep and I used to wake up seeing it all over again, trying to push somebody away because they were dead so somebody else could take their place. Horrible feeling.’

Alf had a powerful message for the children in the class that day:

‘Anybody that tries to glorify war [is] stark raving mad. There should not be wars, there should always be a compromise… Nobody wins, you all lose… It’s all wrong.’

Alf and his pre-war sweetheart, Violet, moved to Hockley in later life. Violet died there in 1991 aged 93. Alf lived until 1997, reaching the age of 99.

Hear from Alf for yourself at our Armistice event on Saturday 10th November 2018, ‘Is this really the last night’? Remembering the end of the First World War. Find full details and booking information here.

Also on 10th November, we will be at Chelmsford Library in the morning running a drawing activity for children based on Gerald’s sketches – find the details here.

First World War stories from ERO’s collections will also be featuring in a remembrance concert at Chelmsford Cathedral in the evening of 10th November – find the details here.