Harlow New Town was established in 1947, when the New Town Development Corporation began to purchase land around the old town and erect new housing estates. The houses primarily served to relieve housing pressures on bombed-out, overcrowded London, particularly from the East End. The first residents began moving in from 1949.

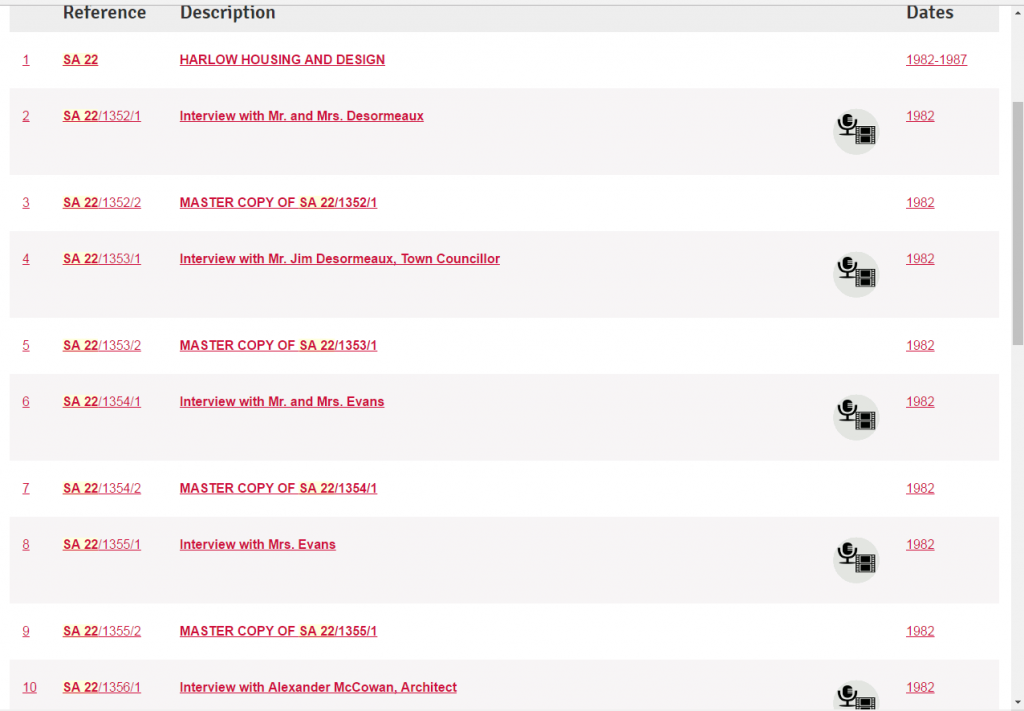

So say the textbooks, but what personal stories lie behind these brief facts? At the Essex Sound and Video Archive, we hold a wonderful collection of oral history interviews conducted by Dr Judy Attfield in the 1980s for her research project, Harlow Housing and Design (SA 22). These interviews reveal what it was like to live in the new town. Our Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place, has enabled us to digitise all of the original cassettes and make them freely available through Essex Archives Online.

At first, we thought the digitisation would be a straightforward task. Shortly after the collection was first deposited with us in 1996, we created access copies on cassette, to safeguard the original masters (our standard procedure in the Sound Archive). The access copies are all neatly labelled and clearly identified, one cassette per interview.

However, when we looked in the box containing the original cassettes, things were not quite so straightforward. We digitise from the original recording (or as near to the original recording as we can get), to capture the purest sound. On revisiting the masters, we realised that the interviewer had used one cassette for multiple interviews – a common practice when you want to make the most of the cassette tape you have. Piecing each recording together to make one complete interview has caused our digitiser, Catherine Norris, several headaches.

But now they are all digitised. Similar to our procedure with physical analogue recordings, we keep a master, uncompressed .wav file safely in storage. We then create compressed .mp3 copies as our new access copy. You can still come into the Searchroom and listen to the recordings, but you can also now listen from home, through Essex Archives Online.

Each interview is valuable in its own right, but as a collection it is even more fascinating. Dr Attfield spoke to a range of people: developers, architects, and town councillors who shed light on the planning of the new town; shopkeepers; people who moved to Harlow before the new town; and people who moved as part of the new town settlement. Putting these different viewpoints together gives a rich, rounded impression of this time in history. Some interviewees say that women found it more difficult than men to settle in new towns and felt lonely and depressed; some say that women found it easier to form new bonds because they were surrounded by women in a similar position, raising children away from their parents in unfamiliar surroundings. Some were ecstatic to have their own front doors, their own staircases in two-storey homes; some missed the familiarity of London, even if they were living in cramped, shared housing. The multiplicity of memories challenges generalisations about life in a new town. It also demonstrates (by listening to the accents of the interviewees, if nothing else) that not everyone in Harlow in the 1950s was an ex-Eastender.

The collection also serves as a good example of how to conduct an oral history interview. Dr Attfield had a specific interest in the interior design of the new houses. She directed questions to gather information on this topic. However, she also asked wider questions for context. She let her interviewees say what they wanted with minimal interventions, but also guided the interview to cover her set of questions. Occasionally she probed her interviewees for more details, or challenged their viewpoints to get a better understanding, without revealing any judgement of their opinions.

Dr Attfield made a significant research contribution in the fields of material culture, gender studies, and design history, among other overlapping areas. Based for many years at the Winchester School of Art, her book Wild Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life (Oxford: Berg, 2000) has become a key text in her field. She passed away in 2006. We are very grateful that she deposited her recordings about Harlow with us, for future researchers to use and enjoy.

One particularly moving interview from the collection is that with Mrs Summers, who moved to the new town from Walthamstow in 1952 (SA 22/1364/1). At several points in the interview, Mrs Summers describes the long adjustment period when ‘home’ still meant London before completely settling in Harlow. As well as missing her family, in this clip she describes how she ‘couldn’t get used to the newness of things’ after coming from Walthamstow with its ‘houses with big windows… little tiny houses… nice houses… [and] grubby-looking houses’.

At a time when neighbourhood plans for vast numbers of additional houses are being developed across Essex – across the country – perhaps these experiences of new settlers can help with the process of creating new communities.

Dr Attfield published an article based on these interviews in the book that she co-edited with P Kirkham, A View from the Interior: Women and Design (London: Women’s Press, 1995). The article can be consulted at Colchester Library.

We hope to showcase clips from these recordings on a listening bench in Harlow, in time for the 70th anniversary of the New Town in 2017. If you are interested in helping to work on the bench for Harlow, please get in touch: info@essexsounds.org.uk