What is the most Christmassy recipe you can think of? Does it help if we sing a song?

“Little Jack Horner

Sat in the corner,

Eating a Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

And said, “What a good boy am I!”

So, to help get us in the festive spirit, we decided to explore the different variations of plum cake recipe’s in our own archives:

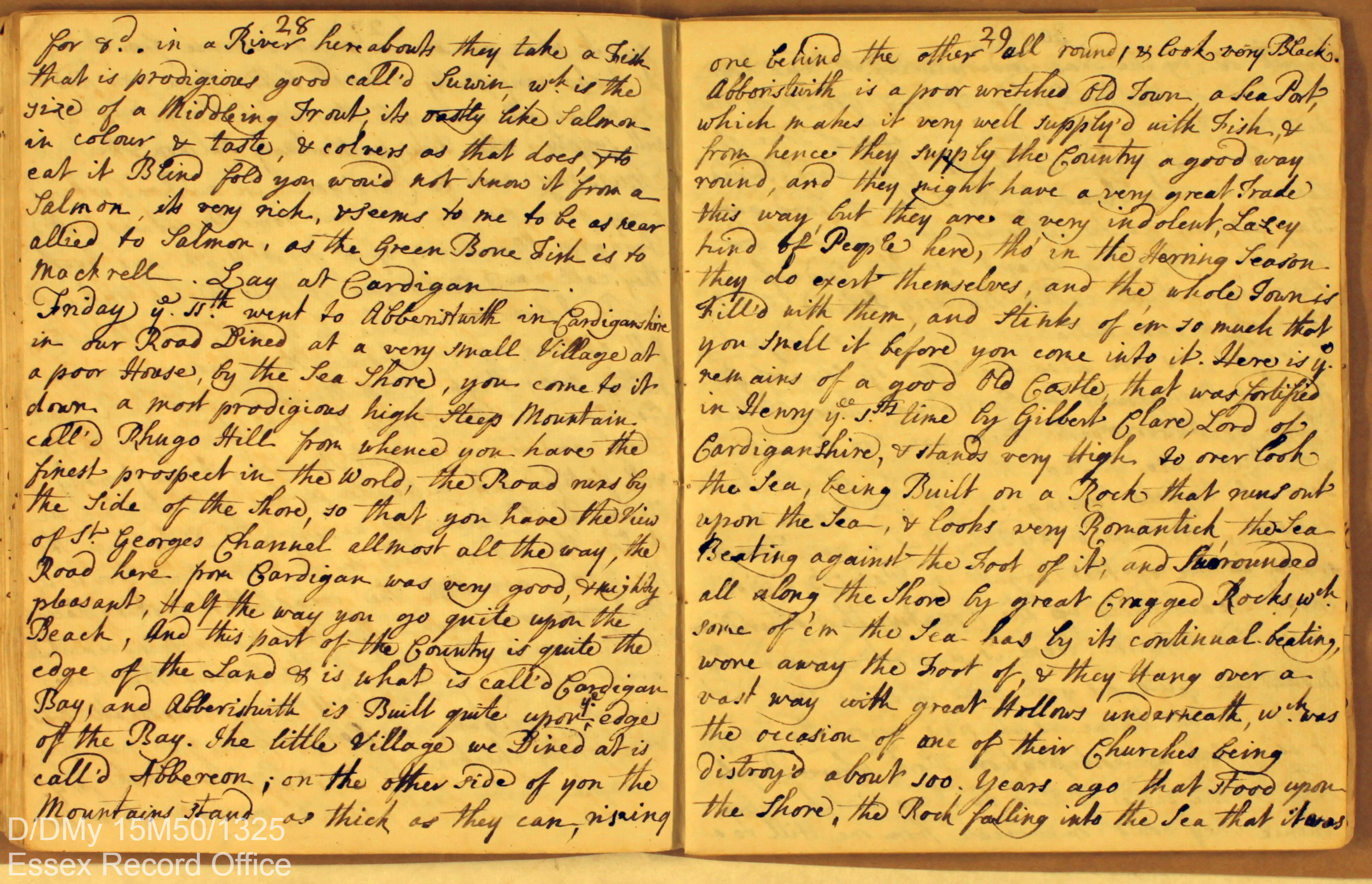

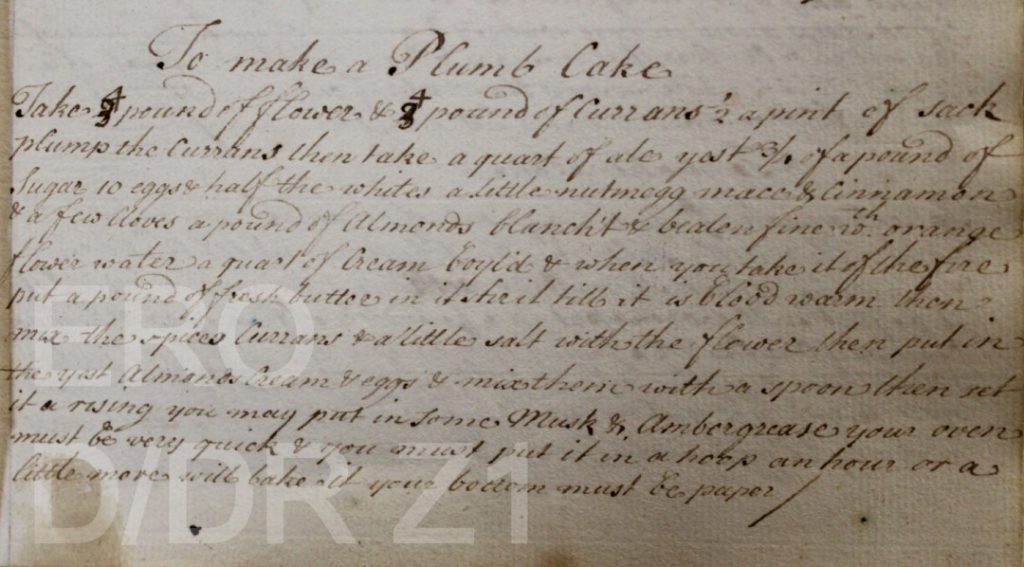

‘To Make a Plumb Cake’ by Elizabeth Slany (c.1715)

“Take 4 pound of flower and 4 pound of currans ½ a pint of sack plump the currans then take a quart of ale yest ¾ of a pound of sugar 10 eggs & half the whites a little nutmeg mace & cinnamon & a few cloves a pound of almonds blanch’t & beaten fine orange flower water a quart of cream boyl’d + when you take it of the fire put a pound of fresh butter in it heit [heat] till it is blood warm then mix the spices currans & a little salt with the flower then put in yest almonds cream eggs & mix them with a spoon then set it rising you may put in some musk & ambergrease [a waxy substance that originates in the intestines of the sperm whale, with a pleasant smell, which is also used in perfumery]your oven must be very quick and you must put it in a hoop an hour or a little more will bake it your bottom must be paper.”

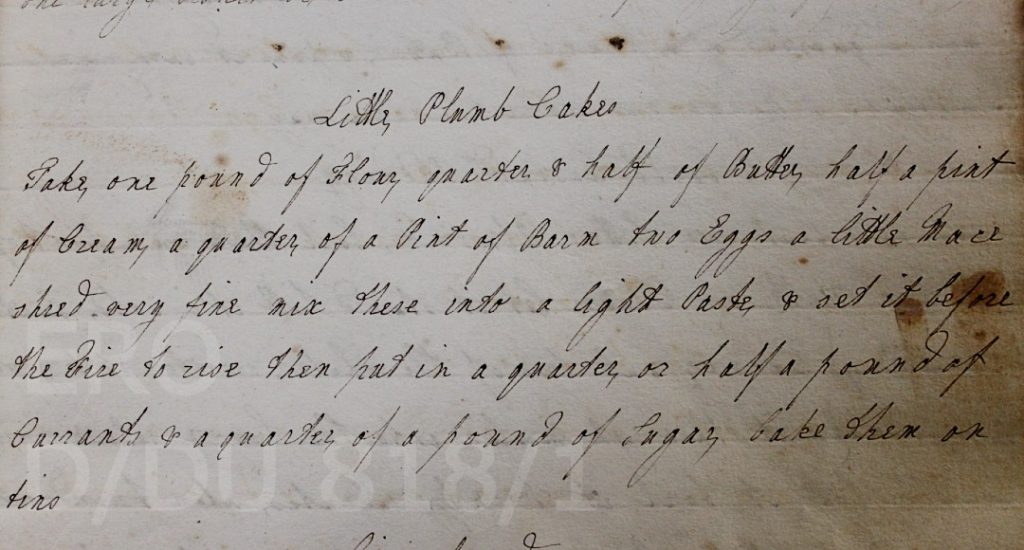

‘Little Plumb Cakes’ by Mary Rooke (c.1770-1777)

“Take one pound of flour, six ounces of butter, half a pint of cream, a quarter pint of yeast, two eggs, a little mace shred very fine, mix these into a light paste, and set it before the fire to rise, then put a quarter or half a pound of currants and a quarter of a pound of sugar, bake them on tins.”

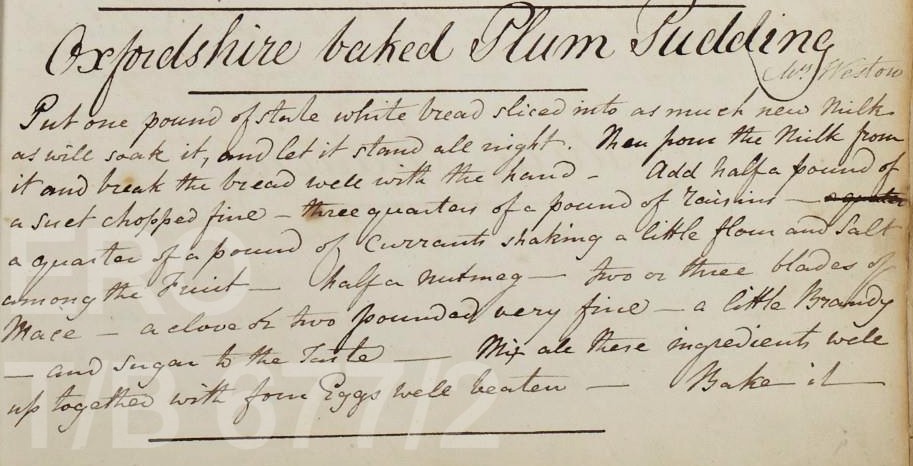

‘Oxfordshire Baked Plum Pudding’ by the Lampet Family (c.1807-1847)

“Put one pound of stale white bread sliced into as much new milk as will soak it, and let is stand all night. Now pour the milk from it and break the bread well with the hand – add half a pound of a suet chopped fine – three quarters of a pound of raisins – a quarter of a pound of currants shaking a little flour and salt among the fruit – half a nutmeg – two or three blades of mace – a clove or two pounded very fine – a little brandy – and sugar to the taste – mix all these ingredients well up together with four eggs well beaten – bake it.”

Let’s play spot the difference!

- The Lampet recipe is probably the most different: it uses bread with only a little extra flour, swaps butter for milk, and is the only recipe to use suet and alcohol.

- Elizabeth Slany’s recipe has some of the most unusual ingredients such as musk and ambergrease, and orange flower water.

- All three recipes use: eggs, currants, mace, yeast, and sugar.

- Elizabeth Slany and the Lampet Family add nutmeg and clove for extra flavour

- None of the recipes include plums!

Do you make plum cake/plum pudding for Christmas? Which of these recipes is most similar to your own?

If you want to see more festive recipes, we currently have Mary Rooke’s recipe book on display in the Searchroom for a seasonal Curiosity Cabinet. Recipes on display include gingerbread and the various components of a mince pie!