Back at the end of March Ian Beckwith kindly shared with us some of the fruits of his research he had undertaken on digital images of Parish Registers

(Essex Archives Online: Parish Registers – what will you find?) accessed through our subscription service on Essex Archives Online. So, although the physical building may be closed for the time being, research is still possible and we enjoyed Ian’s piece so much we thought we’d ask our friends from Mersea [Island] Archive Research Group to share with us just a taste what they have found by looking through wills, of which we look after over 69,000 covering the years 1400-1858. We hope you find it as motivating as we have and, perhaps, it will tempt you to have a go yourself.

Mersea Wills

A year ago, in a world now so remote from the unfamiliar present, a new group was set up at Mersea Island Museum. To some attending the AGM at which this proposal was agreed, it offered an exciting and challenging project: to others, it may have seemed as dull as ditchwater, but worth a try. Now, after the first, gratifyingly successful year, our fortnightly meetings have been brought to an abrupt halt by the unprecedented coronavirus lockdown. In place of sociable discussions over coffee and biscuits, we now try to spend some of our hours of isolation in continuing local researches, communicating online and building on our previous shared learning experiences.

Our group goes by the initials MARG: Mersea Archive Research Group. Its aims are to help members acquire the basic skills of palaeography and to develop and extend these skills by transcribing some of the wonderful local documents preserved in Essex Record Office (ERO). We concentrate on the plentiful records from Mersea Island and nearby villages during the tumultuous Tudor and Stuart periods. Before the enforced closure, we hoped to visit ERO to see original documents, but after the first, enjoyable visit by six members, this was of course no longer possible. The obvious alternative, and one which protects fragile archives from excessive handling, is to make more use of ERO’s increasing collection of digitized documents, which currently include thousands of Essex wills and all available parish registers. We are lucky to have such a wonderful resource available to download on payment of subscription for a variable period. Local appreciation is shared by historians outside the county – an email I received last week from a fellow researcher, commented that ‘You are so lucky with all of the digital resources from the Essex Record Office – as I found out with my Repton project as my local archive has not got nearly as many.’

So often, studying these documents can suddenly reveal an unusual, shocking or moving event recorded, almost incidentally, among pages of routine items. In his ERO Blogpost of 27 March, Ian Beckwith told a tragic story revealed by an entry in Great Burstead’s burial register:

Elizabeth Wattes Widdow sume tyme the wife of Thomas Wattes the blessed marter of god who for his treuth suffered his merterdom in the fyre at Chelmesford the xxij day of may in A[nn]o D[o]m[ini] 1555 in the Reigne of queen mary was buryed the 10 [July] 1599 (ERO, D/P 139/1/0, Image 49).

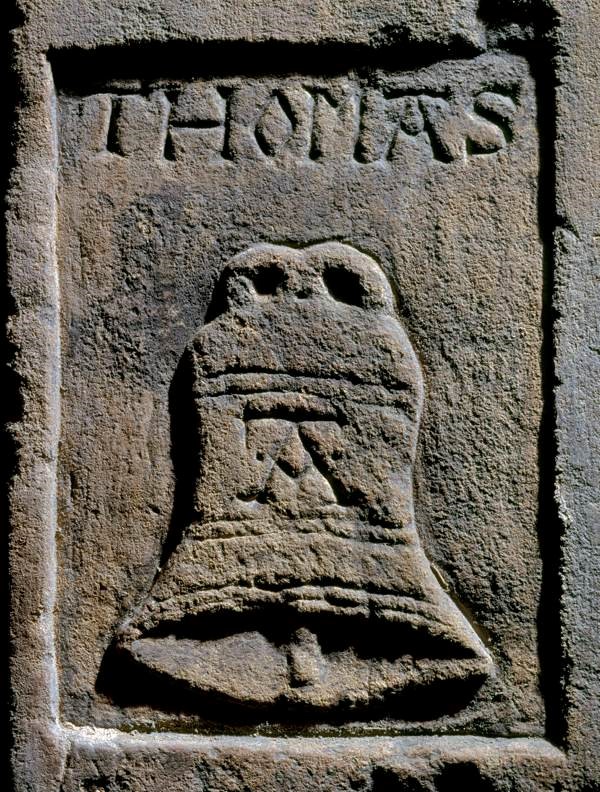

Amazingly, a similar event was revealed in several entries in court records of East Mersea Hall Manor, this time concerning a Roman Catholic rather than Protestant martyr:

It is presented that Thomas Abell, Clark, who of the Lord holds … [one tenement called ] Stone Land; befor this court was Accused and by Acte of parlament Convicte of Treason &c Agaynst our soveraign Lord the kynge, and for that cause he is in the Tower of London in prison. (ERO D/DRc M12, unnumbered folio. This document was not digitized but photographed earlier using the £12 camera fee in the Searchroom )

Thomas Abell was chaplain to Queen Katherine of Aragon, who granted him the benefice of Bradwell juxta Mare. He was imprisoned in 1534 for publishing a book attacking the royal divorce, and after six years in the Tower Abell was hanged, drawn and quartered at Smithfield. In the first year of Queen Elizabeth a letter from the queen was copied into the same East Mersea court book (D/DRc M12), granting all of Thomas Abell’s former holdings, to his brother, John Abell.

Most of the more than forty transcripts completed by MARG members have been digitized wills of the Tudor and Stuart periods. Several members of MARG with subscriptions share downloaded images for discussion with the group, purely ‘for study purposes’. We are aware of strict copyright conditions regarding ERO documents, so images are used only for a couple of weeks while being transcribed by individual members. In some cases where the language is particularly obscure, a modern translation is added. After checking, transcripts are then uploaded to the Mersea Museum website, and can be seen by accessing https://www.merseamuseum.org.uk/mmsearch.php, clicking on ‘Mersea Museum Articles books and papers’ and entering the search-term ‘MARG’. We make sure that no digital images downloaded from ERO are posted on the Mersea Museum website, or available to anyone outside the group.

One way to find refuge from each day’s disturbing Covid bulletins is to lose oneself in the no less anxious times of the 16th and 17th centuries. Wills transcribed over the past year contain a wealth of detail evoking the families, possessions and daily concerns of testators ranging from poor, illiterate villagers to prosperous landowners. Because no lord of any of the Mersea manors chose to live on the island, no great houses were built here. The lords (and lady) of West Mersea lived in splendour at St Osyth’s Priory, almost visible across the River Colne, before the terrors of civil war drove Countess Rivers into exile and bankruptcy. When her great estates and many manors were divided and sold in 1648, Peet and Fingringhoe were sold separately from the previously attached manor of West Mersea, to a rich Irish merchant. His increasing wealth and likely slave ownership were explored by two group members following a hint in the will of his tenant, the widowed Sarah Hackney.

Sarah Hackney’s digitized will (D/ABW 61/125) was made in March 1660/1. She lived in Peet Hall, formerly in the parish of West Mersea, though on the mainland, and the location of most of its manorial courts. Her will specifies the magnificent bequest of £105 and some valuable furniture to her favourite servant, John Foakes, while her brother received the comparatively paltry sum of £15. An apparently unrelated executor received the remainder of her goods and chattels, apart from her clock, to be delivered to her landlord, Thomas Frere, at the end of her lease of Peet Hall. This link led to an investigation of the will of Thomas Frere of Fingringhoe, which yielded far more exotic properties to bequeath. His will (D/ACW 17/114) contains the following unexpected legacies:

Imprimis I give & bequeath unto Thomas Frere my sonne and to his heires executors administrators & assignes All my estate whatsoever both reall and personall in the Island of Barbadoes which was bequeathed unto mee by mr John Jackson my late brother in law & by Elizabeth Jackson his wife my late sister or by either of them or that I have any right or title unto in the said Island of Barbadoes or else where from them or either of them, Alsoe I give & bequeath unto the said Thomas Frere my sonne and to his heires executors administrators & assignees all my landes plantations and other estate whatsoever both reall & personall in the Island of Antigua commonly called Antego.

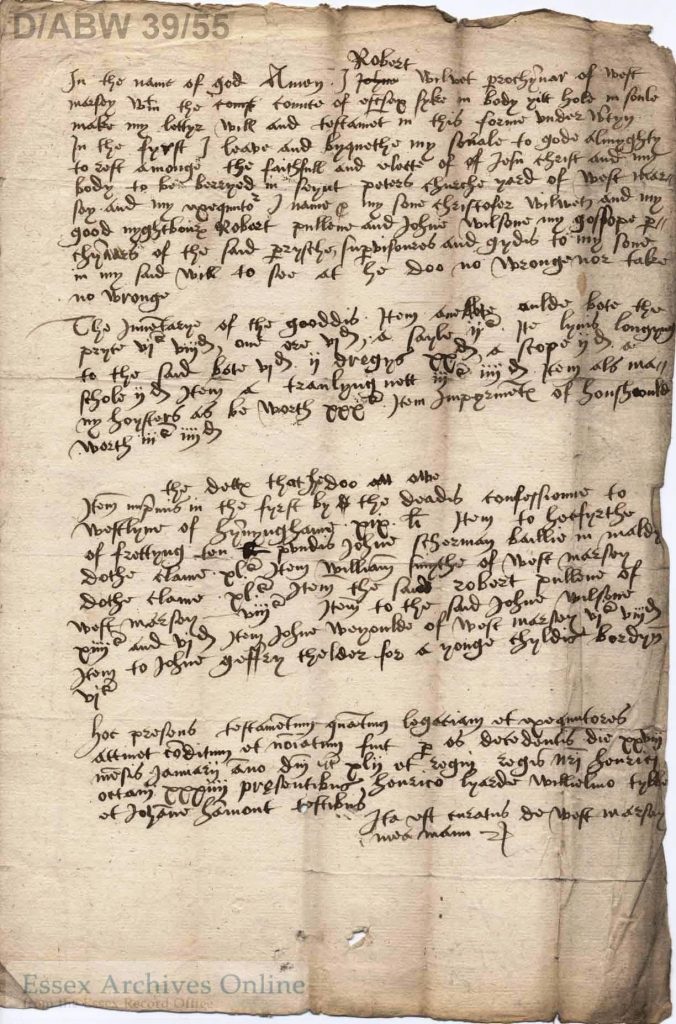

In contrast to the lucrative estates of a probable slave-owner is the situation of Robert Wilvet of West Mersea, who made his short will (D/ABW 39/55) in 1542. The will unusually includes an inventory of his goods, and the many debts totalling nearly £30, which he owed to others on Mersea and beyond.

The very recent changes brought about by the Reformation meant that Wilvet left no precious pennies to the church, simply hoping to be received as one of the ‘faithful and elect of Christ’. Unusually, his will names no specific bequests, even to his son, who, while named as one of three executors, had the other two to be his guides, and ‘see [th]at he Doo no Wronge nor take no Wronge’. The inventory which follows suggests how little there was to inherit: one ‘aulde’ boat worth 6s 8d, one oar, a sail, lines, dredges and a trawling net, plus 30 shillings worth of oysters and household goods worth 3s 4d. Wilvet or his son had little hope of paying off the largest outstanding debt of ‘xix li’ [£19]. However, it is interesting to note that the equipment used by John Wilvet, in his occupation as oyster fisherman, probably changed little until the introduction of marine engines and mechanized trawling gear, many centuries later.

Such brief extracts from wills transcribed by Mersea’s MARG group can only hint at the tantalizing stories that these documents so frequently evoke. While parish registers, rent rolls and property deeds can suggest the bare bones of a person’s life, the documents they dictated to parish priests or literate neighbours as they calmly or fearfully contemplated death, tell a far more complex story. Their possessions, activities, and bonds with family and neighbours, all come to life as we painstakingly transcribe these voices, speaking to us from another age. It is thanks to the preservation of these essentially human records, preserved and now digitized by the skill and dedication of ERO staff, that we can understand more about those who once built and inhabited our local communities.

Sue Howlett

Mersea Archive Research Group