Digital images of the admission registers of the Essex Industrial School and Home for Destitute Boys for 1872-1914 are now available on our online subscription service, Essex Ancestors.

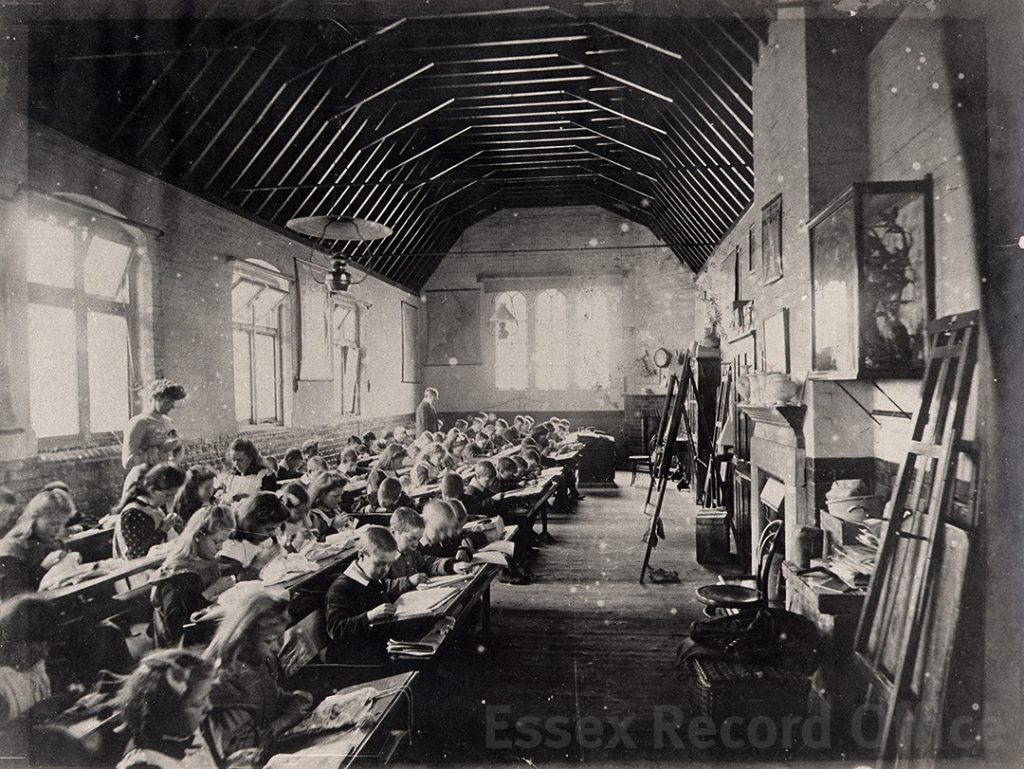

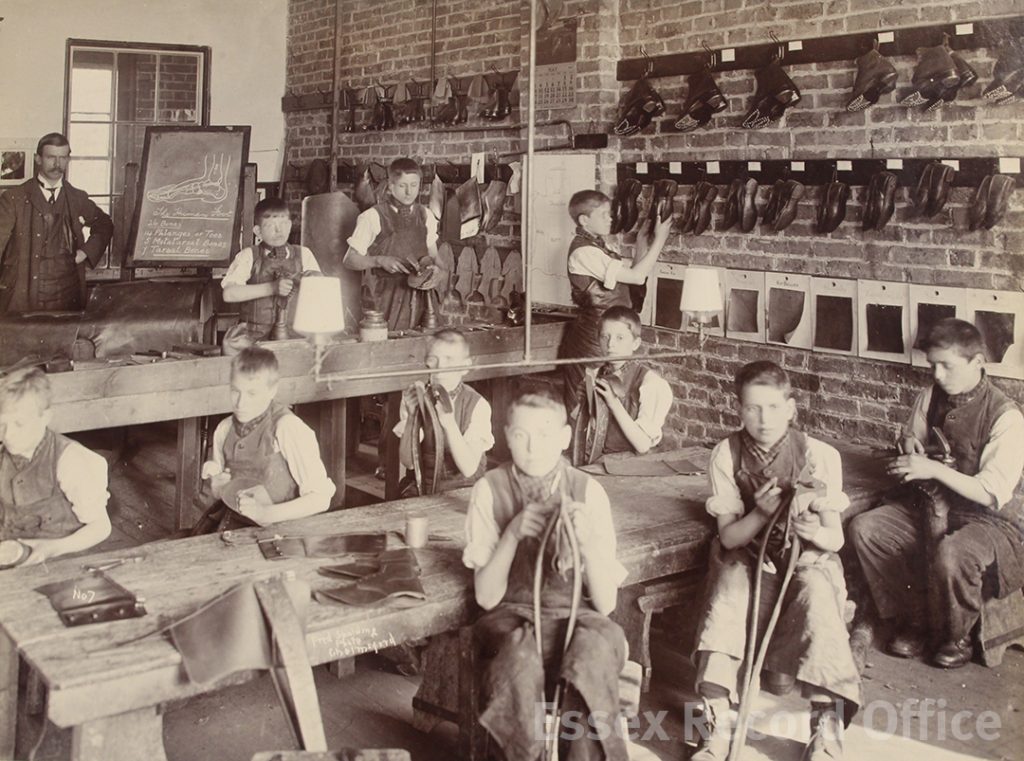

The Essex Industrial School and Home for Destitute Boys gave boys a basic education, and training in practical skills such as shoemaking and carpentry

The school’s admission registers sometimes include incredible detail about the boys who were admitted to the school

We have written before about the fascinating history of the Essex Industrial School, which opened in 1872 in two converted houses in Great Baddow. It was a charitable institution founded by local business man Joseph Brittain Pash, and provided accommodation, a basic education, and practical training for destitute boys, especially orphans or those considered to be at risk of falling into crime. By 1876 the school had grown to fill three houses and four cottages, and in 1879 it moved to a new purpose-built building in Rainsford End, Chelmsford, with space for 150 pupils.

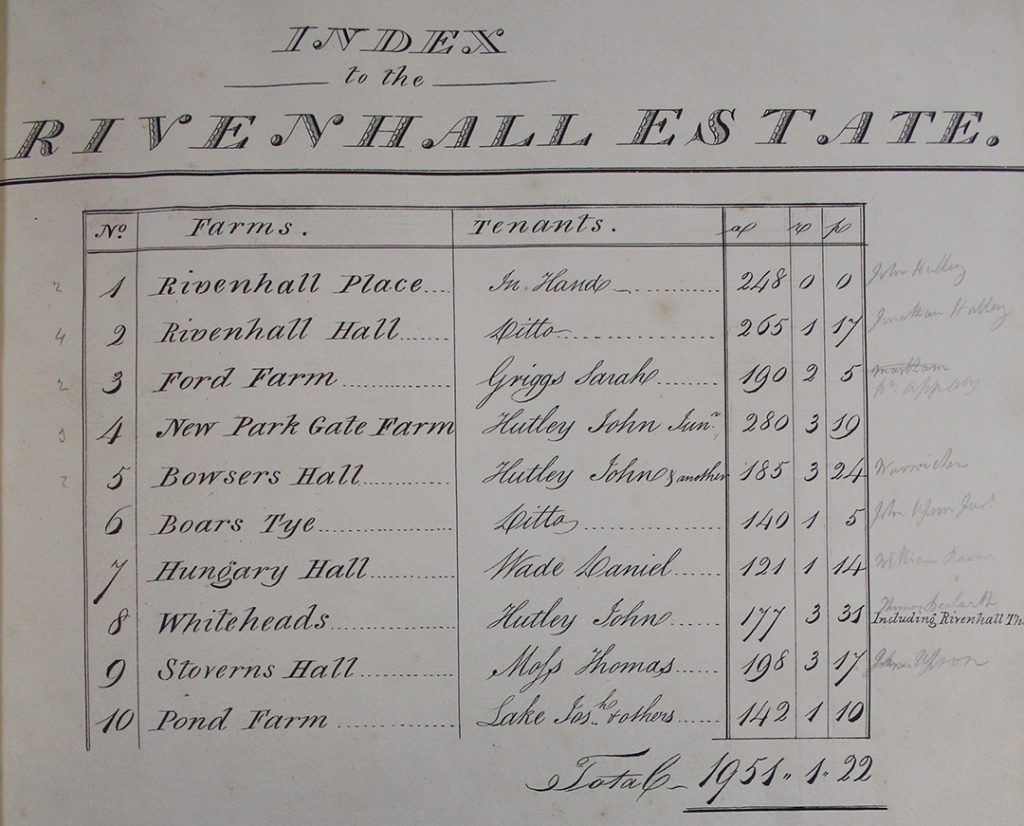

The images which have now been added to Essex Ancestors include admission records for about 1,200 boys who were admitted to the school over this period. Individual records include the reasons for the boy’s admission, and sometimes record information about their progress and what happened to them after they left the school. (Sometimes, as in the case of William Swainston, who emigrated to Canada, it can be possible to find out quite a bit about what happened to the boys after they left.)

These records, especially when combined with information from birth, marriage and death records, census records, and newspapers, can provide some incredibly detailed information about the lives of the boys at the school, and their stories often read like Dickensian novels.

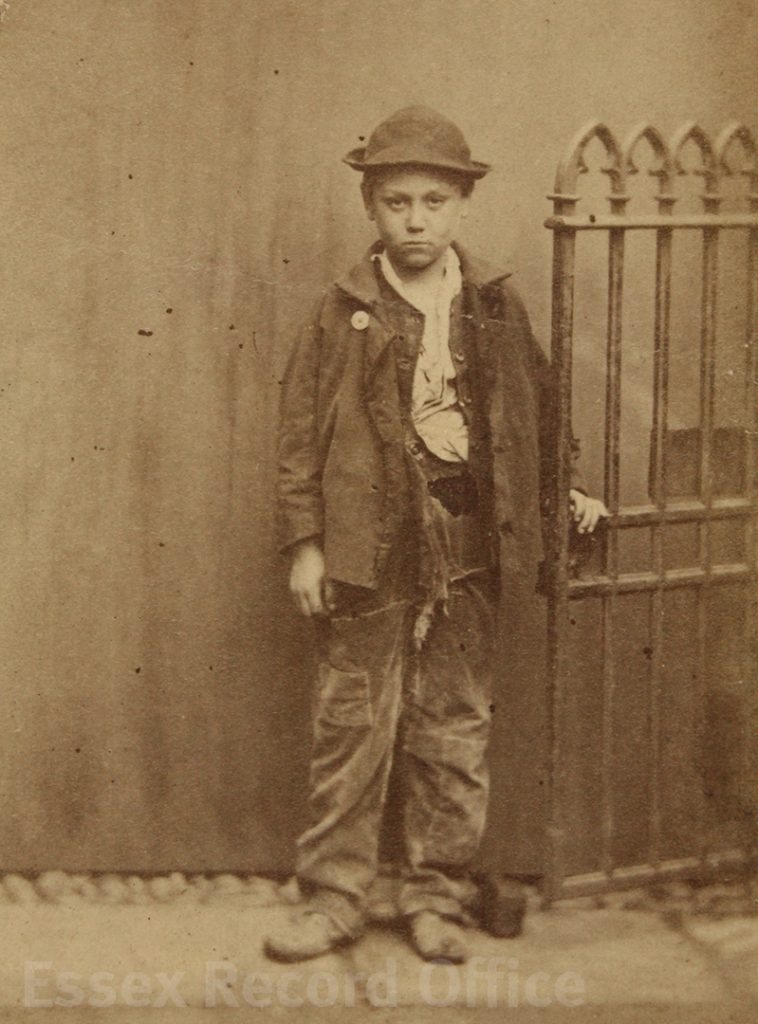

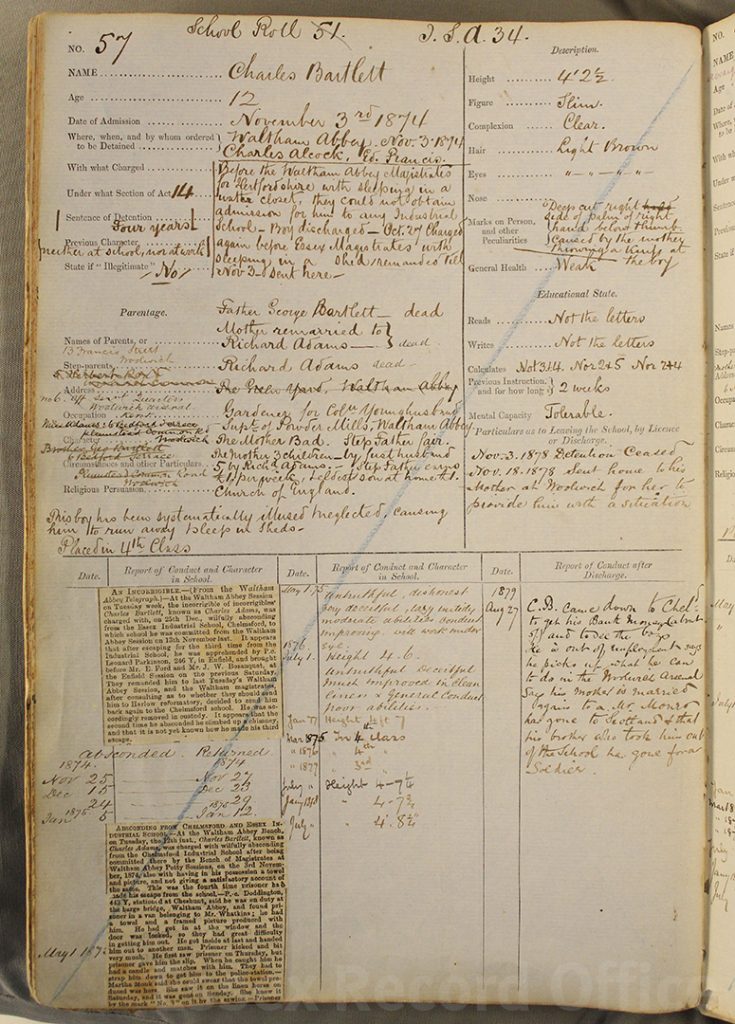

Charles Bartlett, for example, was 12 years old when he was admitted to the school on 3rd November 1874.

Photograph of Charles Bartlett on his admission to the Essex Industrial School (D/Q 40/153)

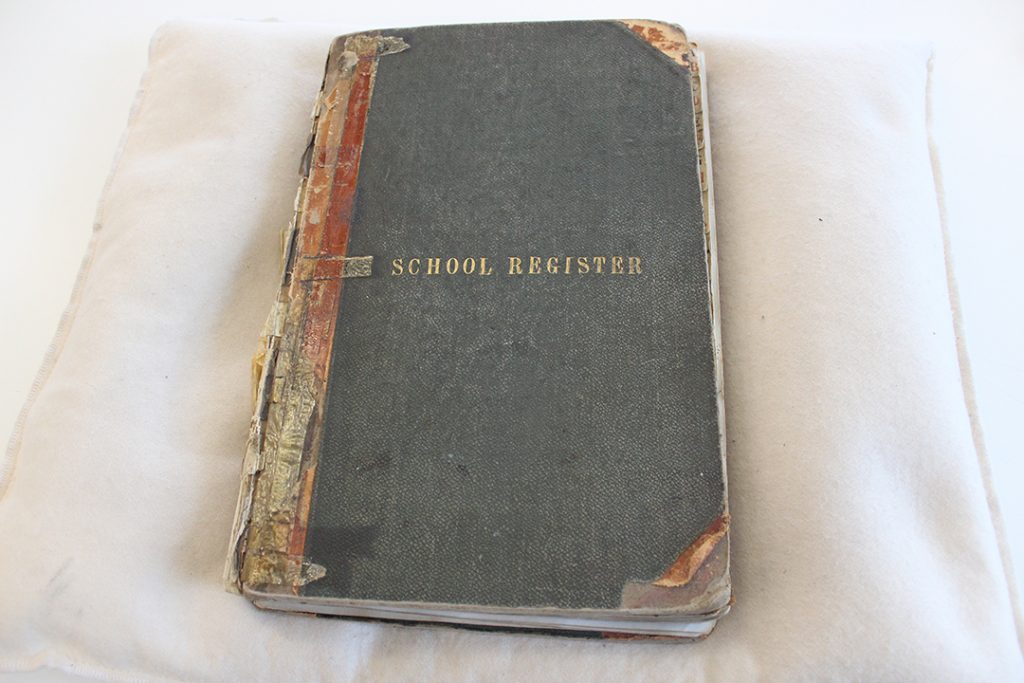

Charles Bartlett’s page in the Essex Industrial School admission registers (D/Q 40/1)

He had been sent by the Waltham Abbey magistrates, where he had twice been brought before the bench for sleeping rough, once in a water closet, and once in a shed. He was sentenced to be detained at the Essex Industrial School for four years.

The details given in Charles’s admission register paint a bleak picture. His father, George Bartlett, was dead. His mother had remarried to Richard Adams. There were three children from the first marriage (including Charles), and five from the second. Richard Adams also died while Charles was at the school. Charles had not received any education and could not read or write. The admission register states that Charles had ‘been systematically illused & neglected, causing him to run away & sleep in sheds’; when admitted he had a deep cut on his hand, apparently caused by his mother throwing a knife at him. (An article found on the British Newspaper Archive from the East London Observer on 7 September 1872 shows that his mother and step-father were hauled before the court after beating Charles so violently that neighbours ran to fetch the police.)

Despite his troubled home life, Charles doesn’t seem to have been pleased to find himself at the school. The register details several occasions where he ran away, only to be returned, sometimes kicking and biting the person who picked him up. On the second occasion he absconded it was thought he had scaled a chimney to escape.

In the end, Charles did remain at the school for his allotted four years. When his time was up in November 1878, he was sent him to his mother at her request. It has been possible to trace him in 1881 in Putney, visiting his mother and her third husband, Charles Munro, and in 1891, living with them in Horley, Surrey. After that the trail has, so far, run cold.

The registers now online are full of stories like Charles’s, and make for fascinating study. The images now available online are from four volumes, with the following catalogue references:

- D/Q 40/1 – the earliest admission register, recording boys admitted in 1872-1881

- D/Q 40/2 – 1883-1897

- D/Q 40/3 – 1897-1911

- D/Q 40/4 – 1911-1914 (this volume includes admissions up to 1925, but records after 1914 are closed)

How to view the records

You can see the digital images of the records for free at the ERO Searchroom and at the ERO Archive Access Point in Saffron Walden.

Instructions on how to take out a subscription are available on the Subscription Service page on Essex Archives Online.

Once logged in and subscribed, use the document reference search box in the top right of the screen to search for the reference of the volume you are interested in.

Going further

If you find a name in the admission registers that you want to follow up, you can try to further trace the individual through census and birth, marriage and death records. Sometimes it is also possible to find newspaper articles about individual cases – the British Newspaper Archive online (which you can access for free at ERO and in Essex Libraries) is an invaluable resource here.

You can also see if any further details are given in the school’s discharge registers. These are not available online, but you can visit us to view them for yourself, or contact us on ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk about remote search and reprographics options.

Best of luck with your research!