Today, 27 July 2016, marks exactly 100 years since the execution of Captain Charles Algernon Fryatt by the German army in Belgium. He was tried by a military court despite being a civilian, and his death sentence was carried out just two hours after his trial, provoking international condemnation.

Fryatt worked for the Great Eastern Railway (GER) Company, captaining steam ships which sailed between Harwich or Tilbury and Rotterdam in the Netherlands. The ships carried post, food supplies and sometimes refugees fleeing the continent. The ships continued to sail during the war, despite the dangers of enemy warships and submarines, blacked out coastlines and floating mines. Here we take a look at the story of Fryatt and the crew under his command as told through the pages of the GER magazine.

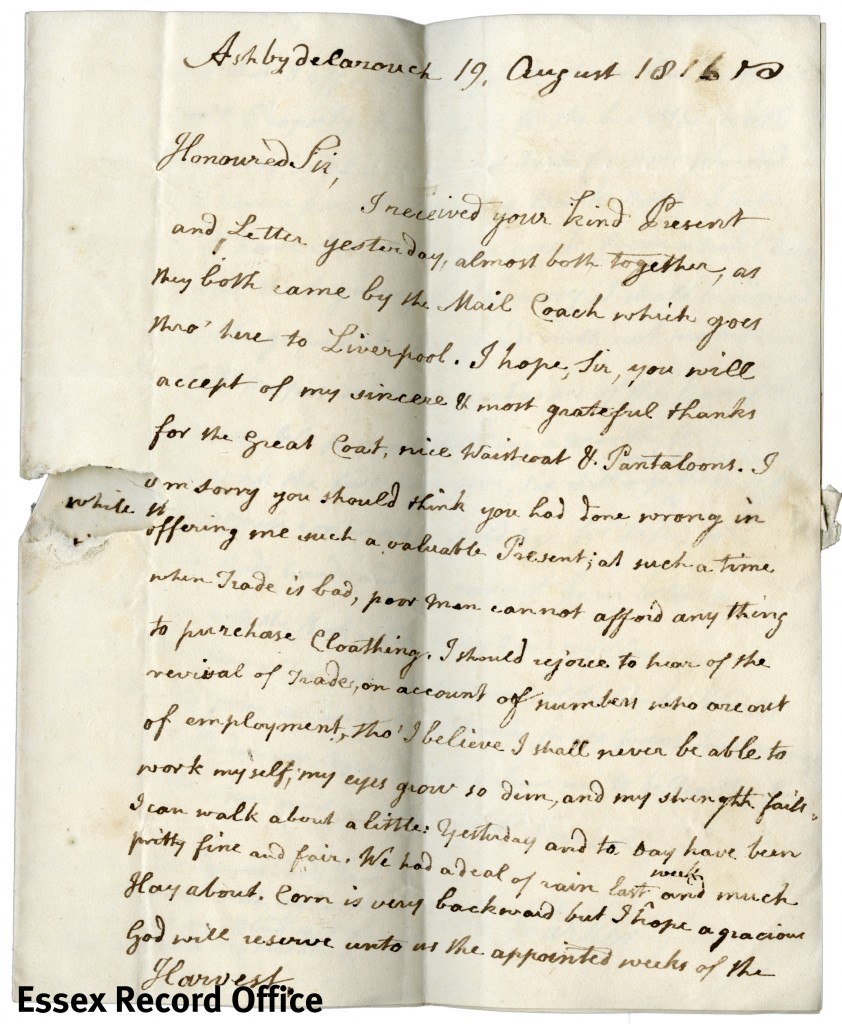

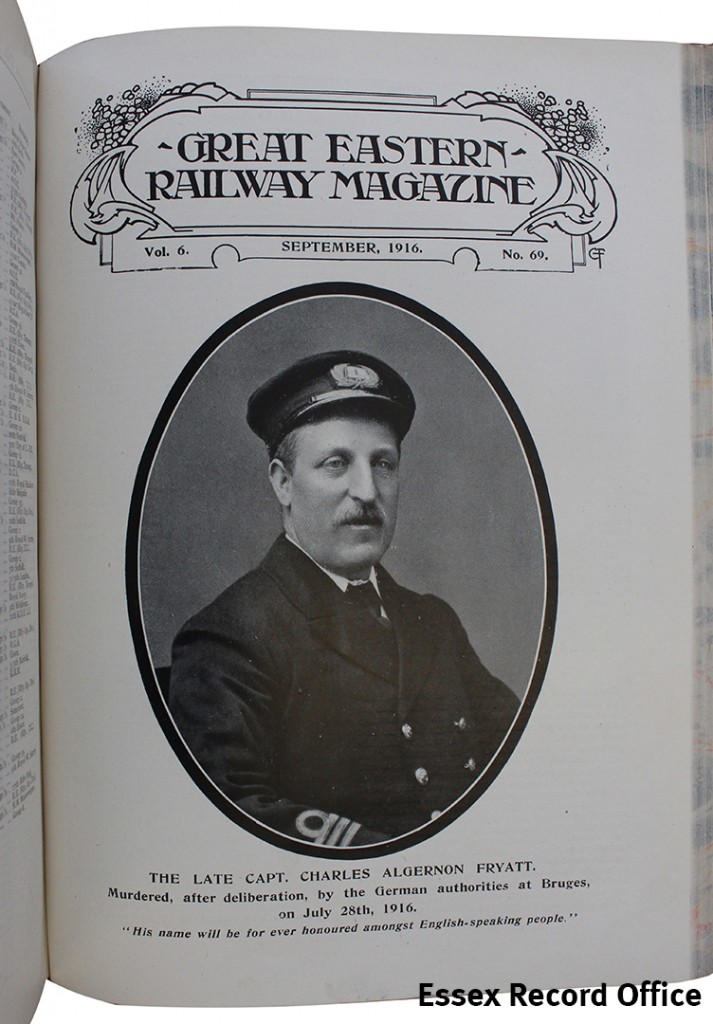

The cover of the September edition of the Great Eastern Railway company magazine focused on the execution of Capt Charles Fryatt

Fryatt lived in Harwich and had joined the GER continental service as a young man in 1892. By the outbreak of the First World War he was a captain, and between the beginning of the war and his capture he made 143 trips across the Channel. The GER ships faced dangerous journeys during the war years, and on more than one occasion were hassled by German submarines. It was a run-in with a German submarine that ultimately led to Fryatt’s capture and execution.

The GER magazine of September 1916 described an incident in which the s.s Wrexham, under Fryatt’s command, had been chased by a submarine:

On March 2nd, 1915, about noon, near the Schouwen Bank, the ‘Wrexham’, proceeding to Rotterdam, was chased for 40 miles by an enemy submarine. Deck hands assisted the firemen to get every ounce of speed, and the enemy’s signal to stop was ignored. They made sixteen knots out of a boat which could hardly be expected to do fourteen knots, and dodging shells and floating mines, as well as the submarine, Captain Fryatt got his boat safely into Dutch waters. She entered Rotterdam with funnels burnt and blistered, the crew black with coal-dust.

A couple of weeks later, on 28 March 1915, Fryatt had a second meeting with a submarine, this time while in charge of the s.s. Brussels. A German submarine was sighted nearby, and the Brussels being unable to outrun it, Fryatt took the decision to attempt to ram it. He ordered the engineers to get all possible speed from the ship, and steered it straight at the submarine, which was forced to dive. Fryatt and others in the GER service were awarded watches for their bravery, but the Germans had different thoughts on the matter.

On the night of 22/23 June 1916, the Brussels, under Fryatt’s command, left the Hook of Holland with a cargo of food and refugees. The ship never arrived in Harwich, and two days later reports reached England that the ship had been captured by the German navy and taken into Zeebrugge in Belgium, then under German control. When the stewardesses were later released their tale was recounted in the GER magazine of November 1916:

After the tiring work of providing for the refugees on board the “Brussels” they were resting, when at 1.30a.m., June 23rd, they noticed the stopping of the engines and heard noises on deck. Chief Steward Tovill said there was trouble and told them to get their life-jackets on. The ship was the prize of five torpedo boats and the Germans were on board. The captain had been hailed in English. For the sake of the women and children he sent no wireless message: if it had not been for them there is little doubt that the Germans would not have been able to take the ship whole.

During the journey to Zeebrugge and then Bruges, ‘the captors on the way enjoy[ed] a most hearty meal. They called for wine but fortunately, think the stewardesses, there was none on board. The stewardesses were kept busy for some five hours serving the Germans and comforting the unfortunate weeping refugees’.

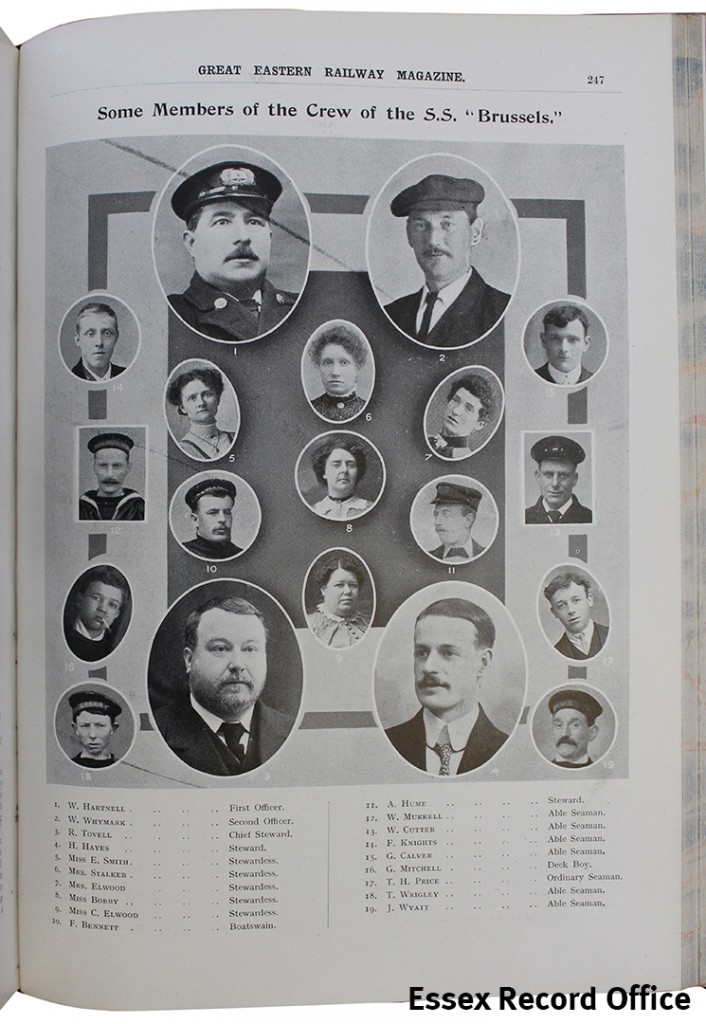

Photographs of some of the crew of s.s. Brussels in the Great Eastern Railway magazine

According to the GER magazine, when the Germans wondered at the calmness of the stewardesses and asked if they were not afraid of being shot, ‘“We are Englishwomen” was considered sufficient reply’.

The crew of 40 men and 5 stewardesses was taken to Bruges and locked up in the town hall, before being scattered to various prison camps. Eventually, postcards from the crew reached Harwich, saying they were well enough but in need of aid packages. Fryatt sent his wife a letter from Ruhleben on 1 July; it only reached her on 29 July, just after his death.

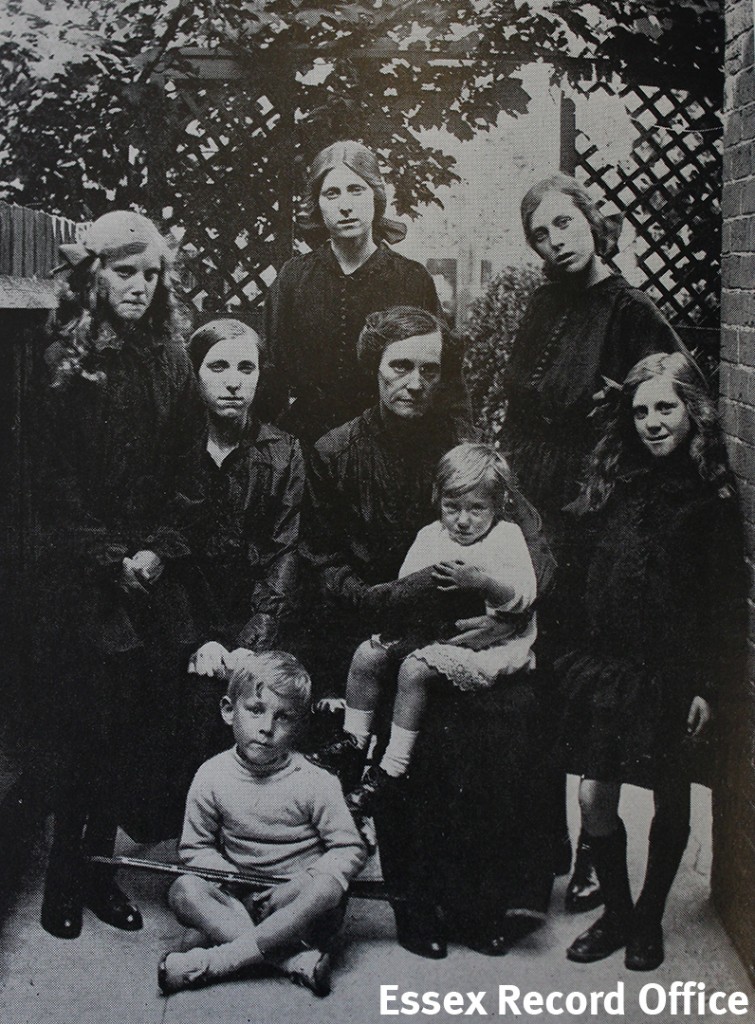

Fryatt and his second-in-command, William Hartnell, were interrogated for three weeks, and on 27 July 1916 were tried by a military court in Bruges. Fryatt was found guilty of attempting to ram submarine U33 on 28 March 1915 and was sentenced to death. The sentence was carried out just two hours later – Fryatt was tied to a post and shot, receiving 16 bullet wounds. His death left behind a widow and seven children, aged between 18 and 2.

The execution of Charles Fryatt provoked a storm of protest in Britain, and was denounced in the strongest terms in Parliament and in the press. The September edition of the GER magazine, in one of its milder statements, said ‘one does not expect a European nation to murder its prisoners of war’.

In its report of Fryatt’s death on 4 August 1916, the Chelmsford Chronicle condemned the German decision to capture and execute him:

The murder by the Germans of Captain Fryatt, who commanded the Great Eastern Railway Co.’s steamship Brussels, brings the fact of German frightfulness home to the country in general, and Essex in particular. The gallant captain’s offence, in German eyes, was that he, in self-defence, attempted to run down and sink and enemy submarine, which by all international law, to which Germany herself subscribed, he was perfectly entitled to do. There seems little doubt, however, that the Germans had planned some time ago to capture the Brussels and her intrepid commander, and when the opportunity came they appear to have lost no time in placing Capt. Fryatt on a trial of a sort and condemning him to death, a sentence which was carried out with feverish expedition, so that the crime they had decided to commit might not be interfered with by a neutral nation…Of course the whole Empire is crying out for vengeance.

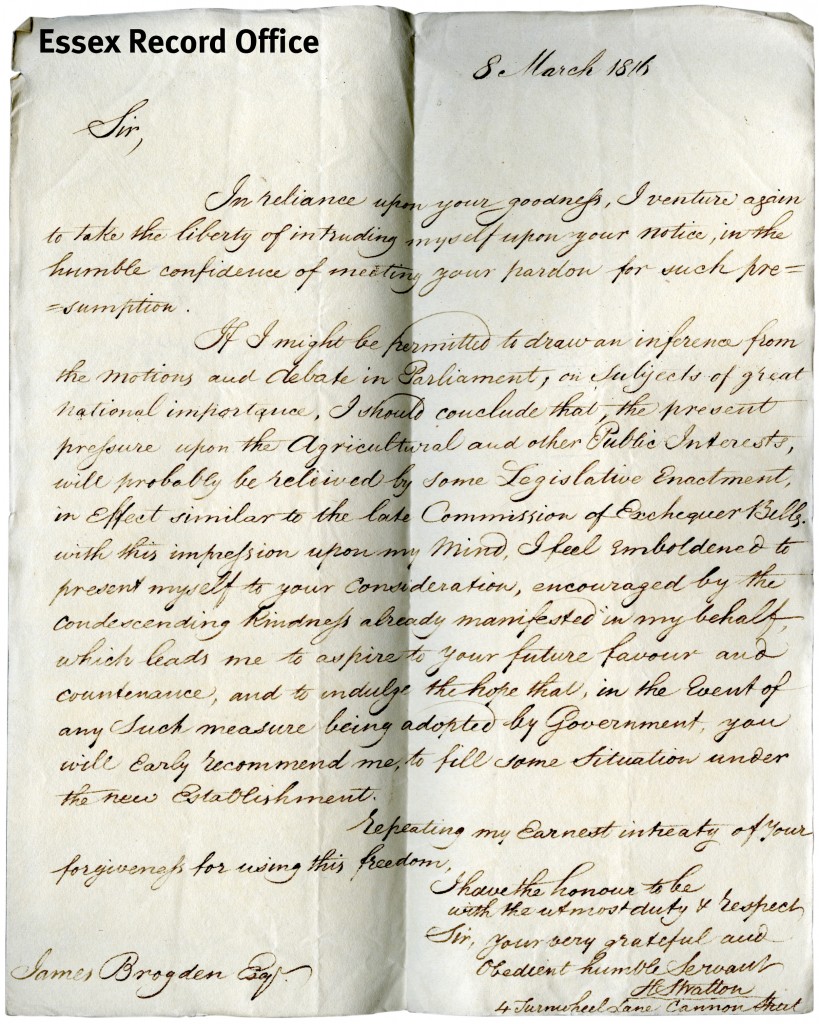

Mrs Fryatt received telegrams of sympathy and support from several high profile people and organisations, including from Buckingham Palace:

Madam,

In the sorrow which has so cruelly stricken you, the King joins with his people in offering you his heartfelt sympathy.

Since the outbreak of the war, His Majesty has followed with admiration the splendid services of the Mercantile Marine.

The action of Captain Fryatt in defending his ship against the attack of an enemy submarine was a noble instance of the resource and self-reliance so characteristic of that profession.

It is, therefore, with feelings of the deepest indignation that the King learnt of your husband’s fate, and in conveying to you the expression of his condolence I am commanded to assure you of the abhorrence with which His Majesty regards this outrage.

At the time of Fryatt’s death, the rest of the crew were still in prison camps. From their initial imprisonment in Bruges the stewardesses were put on a cattle train to Ghent, then sent to Cologne, then a camp at Holzminden near Hanover, then finally deposited at the border with neutral Holland. The GER staff magazine of November 1916 reported:

It was indeed a pleasure and a relief to see again the released stewardesses of the s.s. “Brussels.” Mrs. Elwood, Miss Elwood, Mrs. Stalker, Mis Bobby and Miss Smith have passed through a most trying experience and have done so in a manner of which G.E.R. women can be proud.

The stewardesses of s.s. Brussels while being kept prisoner

After the war, the government decided to repatriate Fryatt’s body, along with the remains of Edith Cavell and the Unknown Soldier. (We have written previously about the papers we have in our collection from Bruges relating to the release of his remains to the British.)

In July 1919, the coffin was exhumed from its grave in Bruges in the presence of Hartnell and Fryatt’s brother William. The Chelmsford Chronicle of 11 July gives a full account of the day of processions and funeral services marking the return and reburial of Fryatt’s remains. The coffin was transported from Antwerp on HMS Orpheus, and was received at Dover with full military honours. To the strains of Chopin’s Funeral March, the coffin was carried to Dover station, and from there taken to London for a funeral service at St Paul’s Cathedral. Music was provided at the service by the orchestra of the Great Eastern Railway Musical Society, and the coffin was placed under the great dome of the cathedral. After the service, the coffin and mourners proceeded to Liverpool Street, and from thence to Dovercourt, where crowds awaited the return of their local hero. At the reburial, the Bishop of Chelmsford said that Fryatt was one of the representatives of the ‘self-sacrificing spirit of the English people’ during the great war.

Next time you pass through Liverpool Street station, see if you can spot the memorial to Captain Fryatt, which today can be found near the exit onto Liverpool Street.