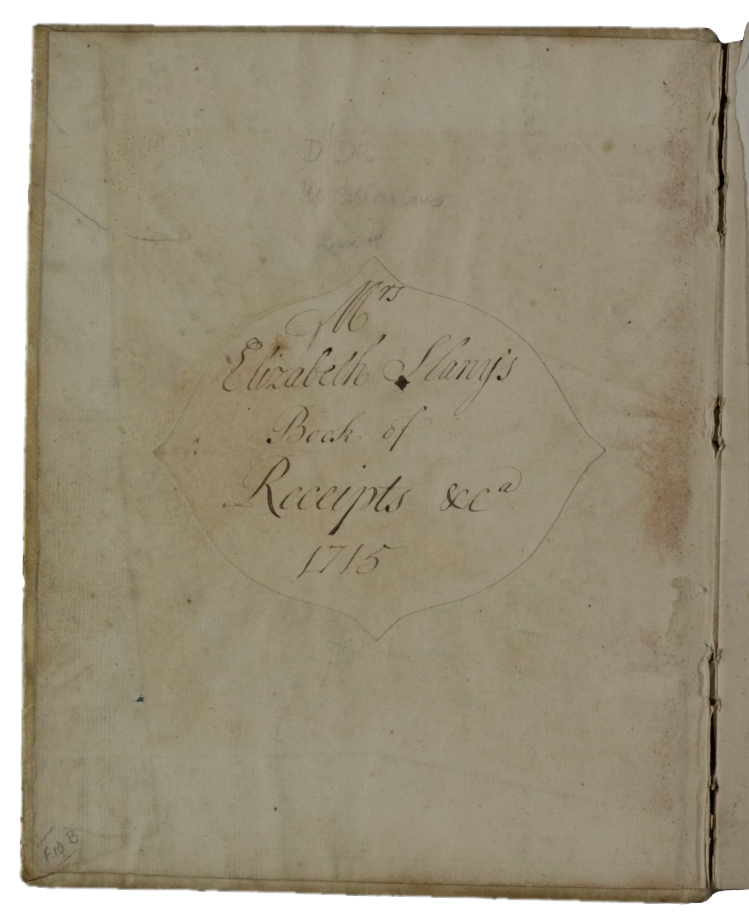

An unseasonably soggy August day seemed a good opportunity to share Elizabeth Slany’s recipe for a ‘Syrup of Turnips for a cold’.

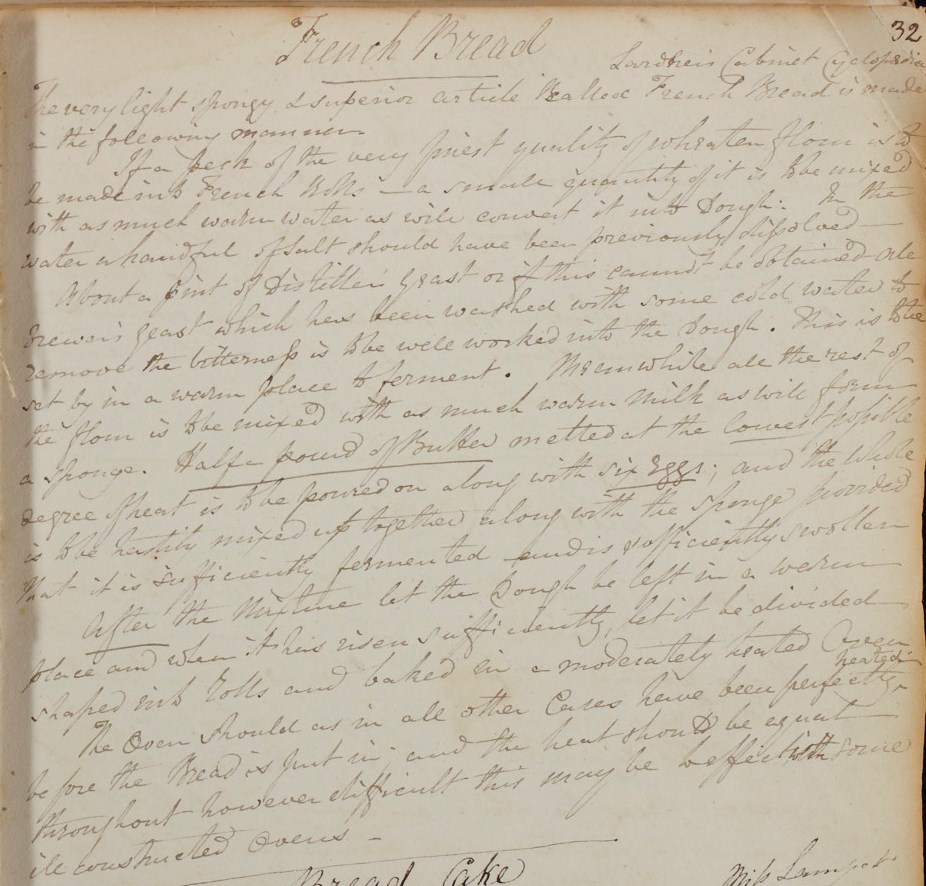

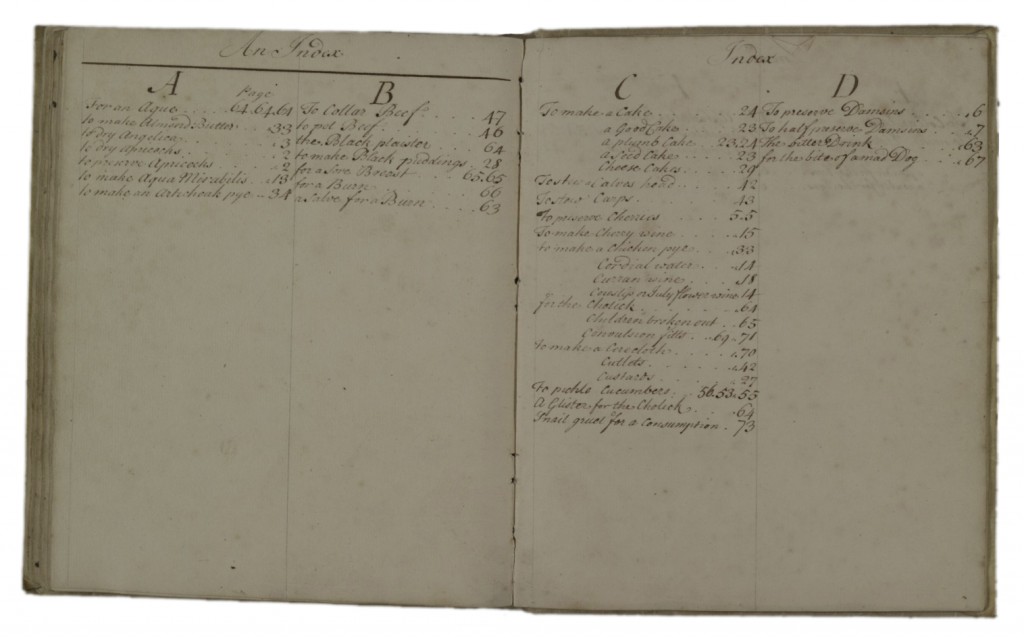

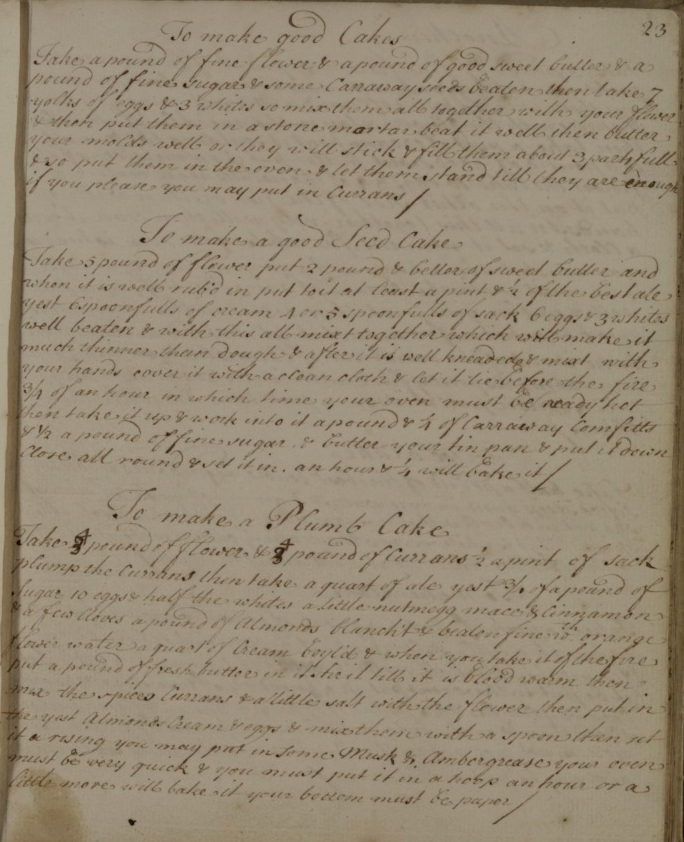

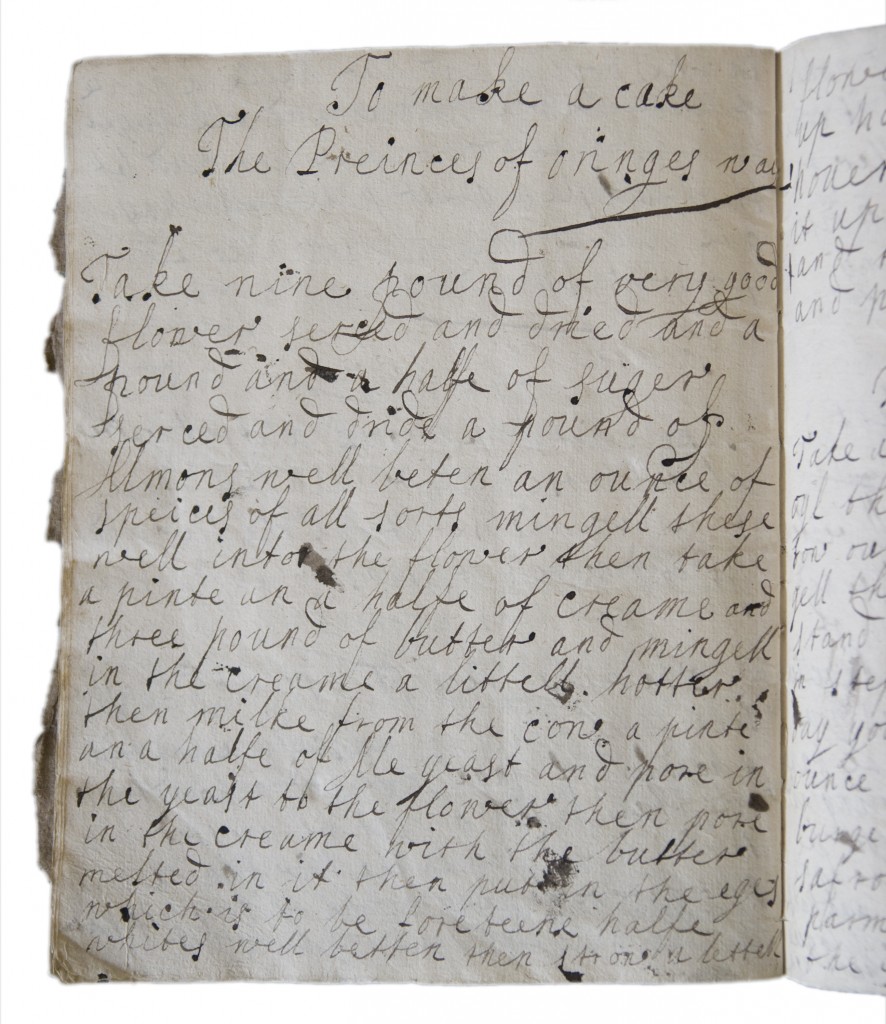

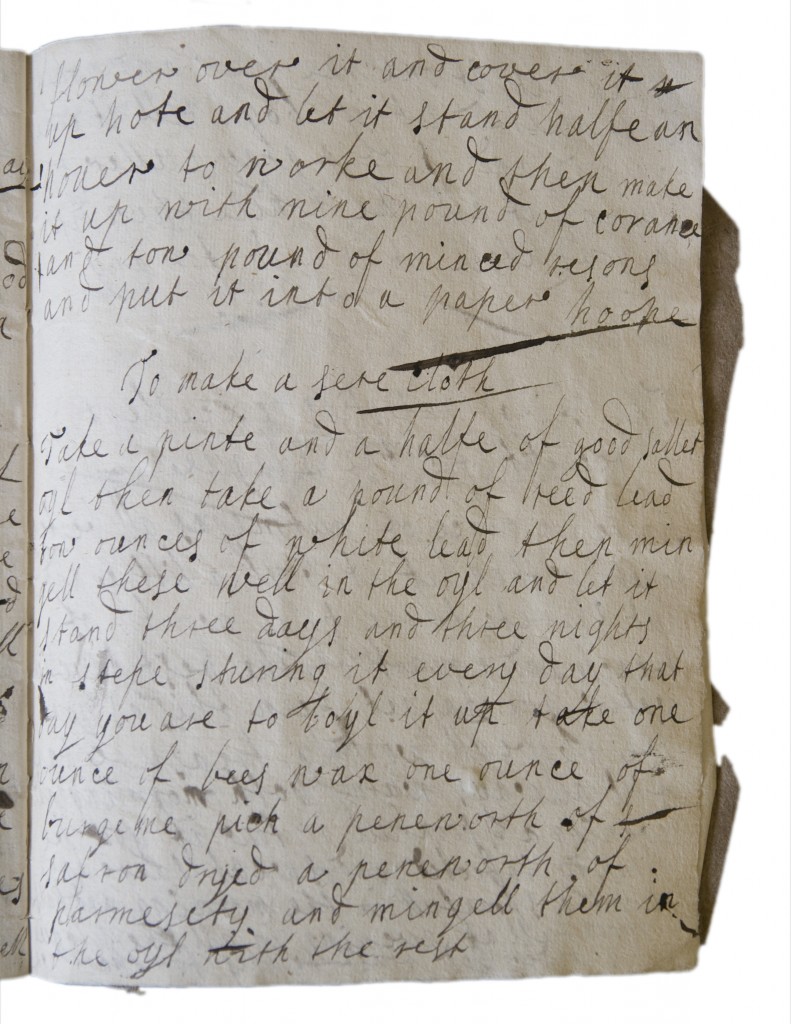

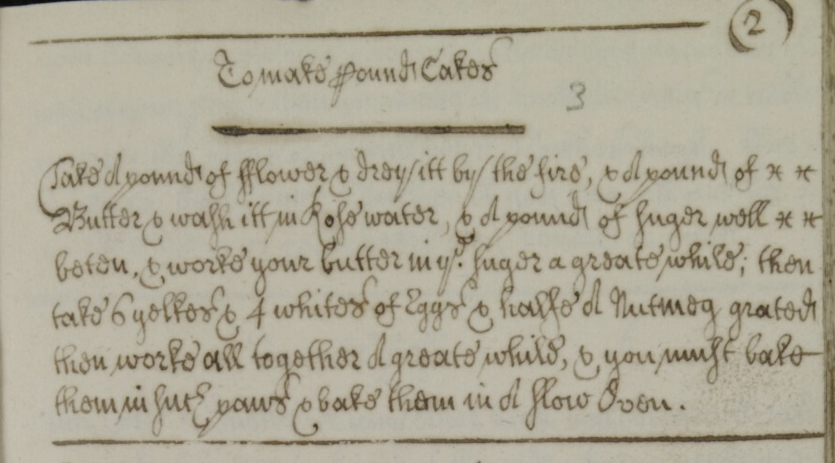

We have written about Elizabeth’s recipes before; her recipe book (catalogued as D/DR Z1) is one of the most substantial recipe books in our collection, and includes recipes for food and drink and medicines for both people and animals, dating from the early-mid 1700s. This recipe comes from the earlier part of the book, which we believe is in Elizabeth’s own writing. To make Syrup of Turnips for a cold

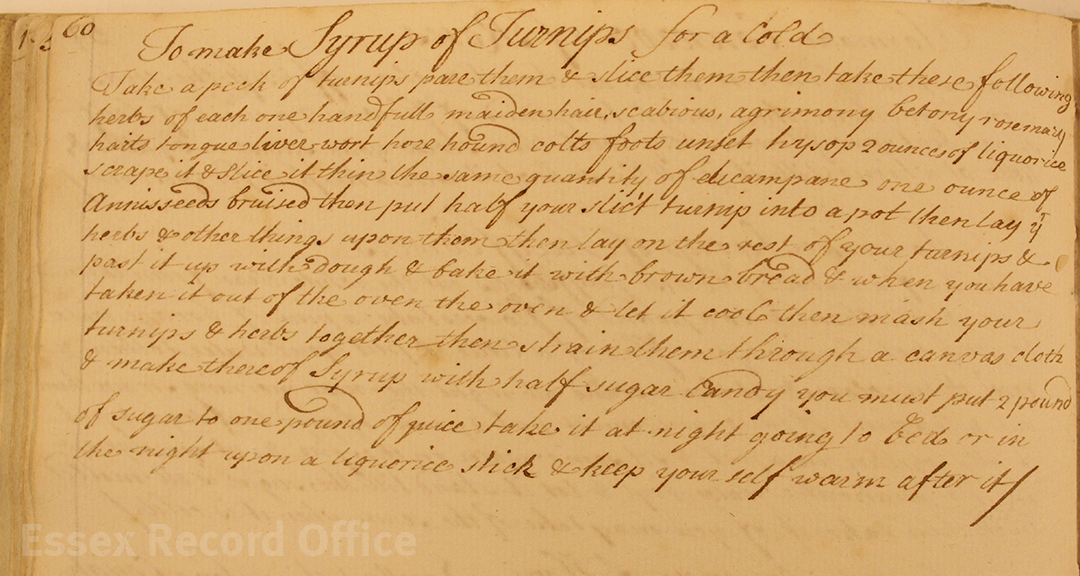

To make Syrup of Turnips for a cold

Take a peck of turnips pare them & slice them then take these following herbs of each one handfull maidenhair, scabious, agrimony betony rosemary harts tongue liver wort hore hound colts foots unset hyssop 2 ounces of liquorice scrape it & slide it thin the same quantity of elicampane one ounce of Annisseeds bruised then put half your slic’t turnip into a pot then lay yr herbs & other things upon them then lay on the rest of your turnips & past it up with dough & bake it with brown bread & when you have taken it out of the oven the oven [sic] and let it cool then mash your turnips & herbs together then strain them through a canvas cloth & make thereof Syrup with half sugar candy you must put 2 pound of sugar to one pound of juice take it at night going to bed or in the night upon a liquorice stick & keep yourself warm after it

Or, to restate it in a way that is perhaps easier for our modern eyes to read:

- Peel and slice a peck (2 gallons) of turnips

- Collect a handful each of the following herbs:

- Maidenhair (maidenhair fern, which was still in use in cough syrups into the nineteenth century)

- Scabious (a plant of the honeysuckle family of flowering plants, traditionally used as a folk medicine to treat scabies)

- Agrimony (a plant which grows slender cones of small yellow flowers with a long history of medicinal use for treatment of a wide range of ailments)

- Betony (a plant with purple flowers used as another ‘cure-all’)

- Rosemary (this fragrant Mediterranean herb has traditionally been used to treat a variety of disorders)

- Hart’s-tongue – also known as hart’s-tongue fern, has been used both internally (e.g. for dysentery) and externally (e.g. for burns)

- Liverwort (a perennial herb with a long history of medicinal use, including for liver ailments, healing wounds, and bronchial conditions)

- Horehound (this herbaceous plant with white flowers has appeared in numerous books on herbal remedies over several centuries, and modern scientific studies have investigated its antimicrobial and anticancer properties)

- Coltsfoot (a member of the daisy family with yellow flowers and hoof-shaped leaves, coltsfoot has been used in herbal remedies for respiratory diseases for centuries, but today it is known to be potentially toxic)

- Hyssop (a plant widely used in herbal remedies, especially as an anti-septic and cough reliever)

- Scrape and thinly slice 2 ounces of liquorice – the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra, which has been used in herbal medicines for sore throats and related illnesses, as well as a range of other conditions

- Elizabeth’s instructions next call for 2 ounces of elicampane, another root. She doesn’t specify how it should be prepared, but it could either be turned into syrup or powdered (elicampane appears in The English Physician Enlarged, With Three Hundred and Sixty-Nine Medicines Made of English Herbs, by Nicholas Culpepper, Gentleman, Student in Physick and Astrology, 1770, which recommends that the roots of elicampane could be preserved with sugar into a syrup or conserve, or dried and powdered then mixed with sugar. Both were recommended for stomach complaints, and ‘to help the Cough, Shortness of Breath, and wheezing in the Lungs.’)

- Bruise one ounce of aniseeds (seeds of the anise plant, used in herbal medicines for a range of complaints including a runny nose and as an expectorant)

- Put half the sliced turnips in a pot, and cover them with the herbs and liquorice, then lay the rest of the turnips on top

- Cover the whole mixture with pastry dough

- Elizabeth’s next instruction is to bake the mixture ‘with brown bread’ – perhaps this means it should stay in the oven for the time it takes a loaf of brown bread to cook but if anyone has any other ideas of the meaning of this do leave a comment

- Remove from the oven – and presumably take off the pastry lid

- Mash the turnip and herb mixture, then strain it through a cloth

- To each 1lb of the resulting juice, add 2lb sugar to make a syrup

- Take the syrup before bed, or during the night, on a stick of liquorice and keep yourself warm after taking it

With a total of 13 ingredients added to the turnip and then plenty of sugar added at the end, this sounds like an elaborate cold remedy, and would presumably have been out of reach of most ordinary people. If you have other historical cold remedies do leave them in the comments below; hopefully we won’t need them as summer wears on but it might be best to be prepared.

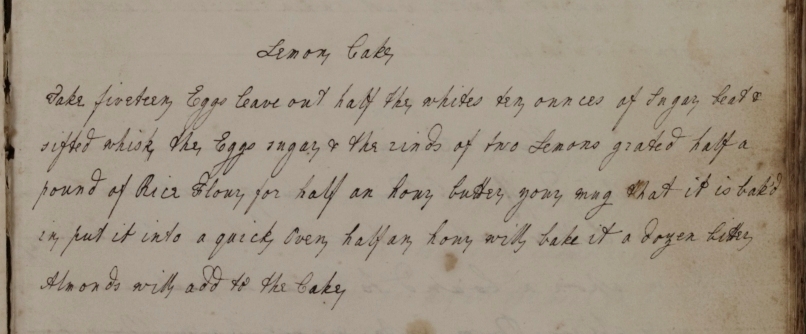

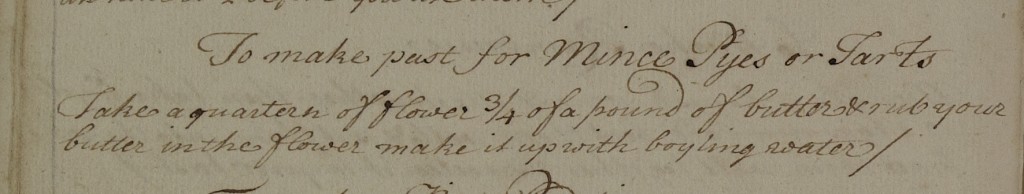

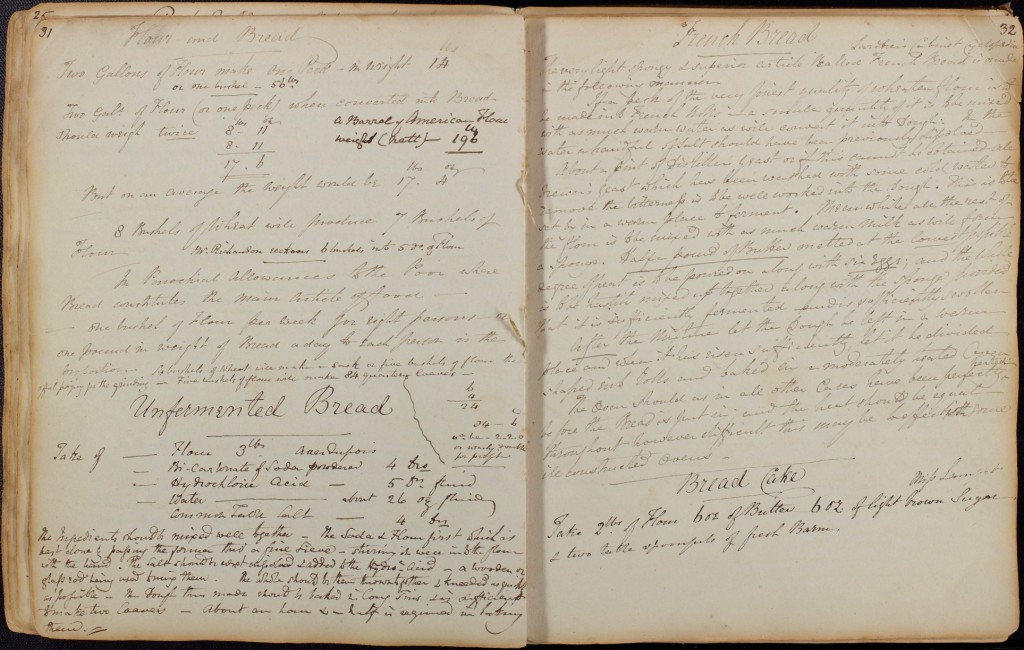

![T/B 677/2 - Unfermented Bread Take of –Flour 3lbs averdupois -Bi-Carbonate of Soda powdered 4 dram -Hydrochloric acid – 5 drams fluid -Water- about 26oz fluid -Common Table Salt – 4 drams The ingredients should be mixed well together – The Soda & flour first which is best done by passing the former thro[ugh] a fine sieve – stirring it well into the flour with the hand. The salt should be next dissolved & added to the Hydro[chloric]-Acid – a wooden or glass rod being used to mix them. The whole should be then thrown together & kneaded as quick as possible – The Dough thus made should be baked in long Tins and is sufficient to make two loaves – about an hour & a half is required in baking them.](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/T-B-677-2-a.jpg)