In the twelfth and final post from our Chelmsford Then and Now project, student researcher Ashleigh Hudson explains how during her research project we used maps to establish areas of continuity and change in the High Street of our county town.

A key objective of the Chelmsford Then and Now project was to establish what has changed and what has stayed the same over time in the centre of our county town. We are lucky that Chelmsford has been mapped and re-mapped several times over the centuries, enabling us to make comparisons over time, and to find traces of the medieval town in today’s High Street, even though no buildings from that period survive. In this post we will show how we have used maps in this project to look at the detailed history of specific properties.

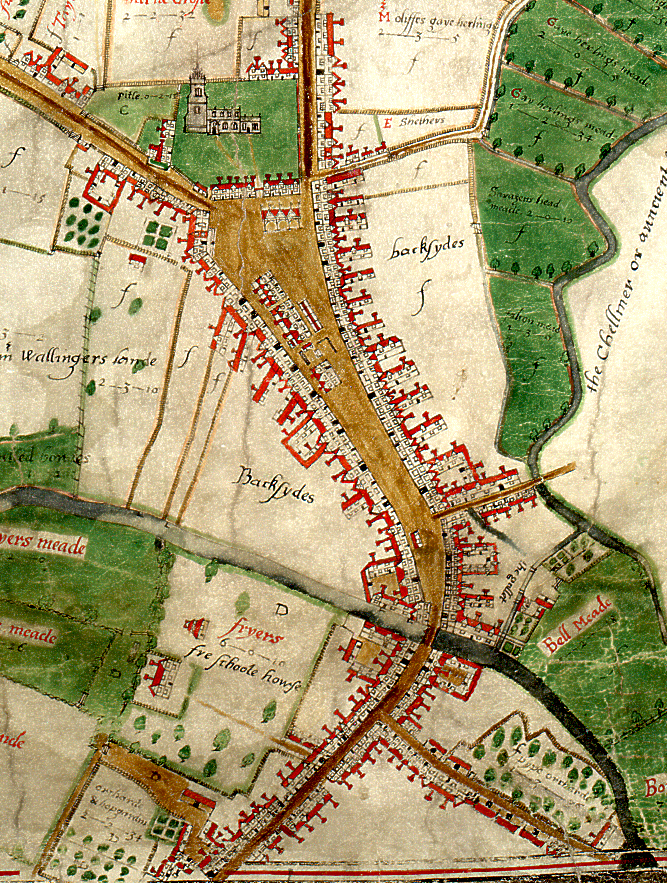

The earliest known map of Chelmsford was drawn up by John Walker in 1591. The shape of Chelmsford High Street, as depicted on the Walker map, is remarkably similar to the shape of the high street today; in fact the basic make-up of the town has not changed in nearly five hundred years. Internally, the shape and size of individual properties has varied significantly over time, reflecting changing economic, demographic and technological trends. The 20th century in particular saw sweeping changes to areas of the high street. As the town’s population increased, the demand for more retail spaces grew, and the arrival of department stores facilitated the absorption of many of the smaller businesses.

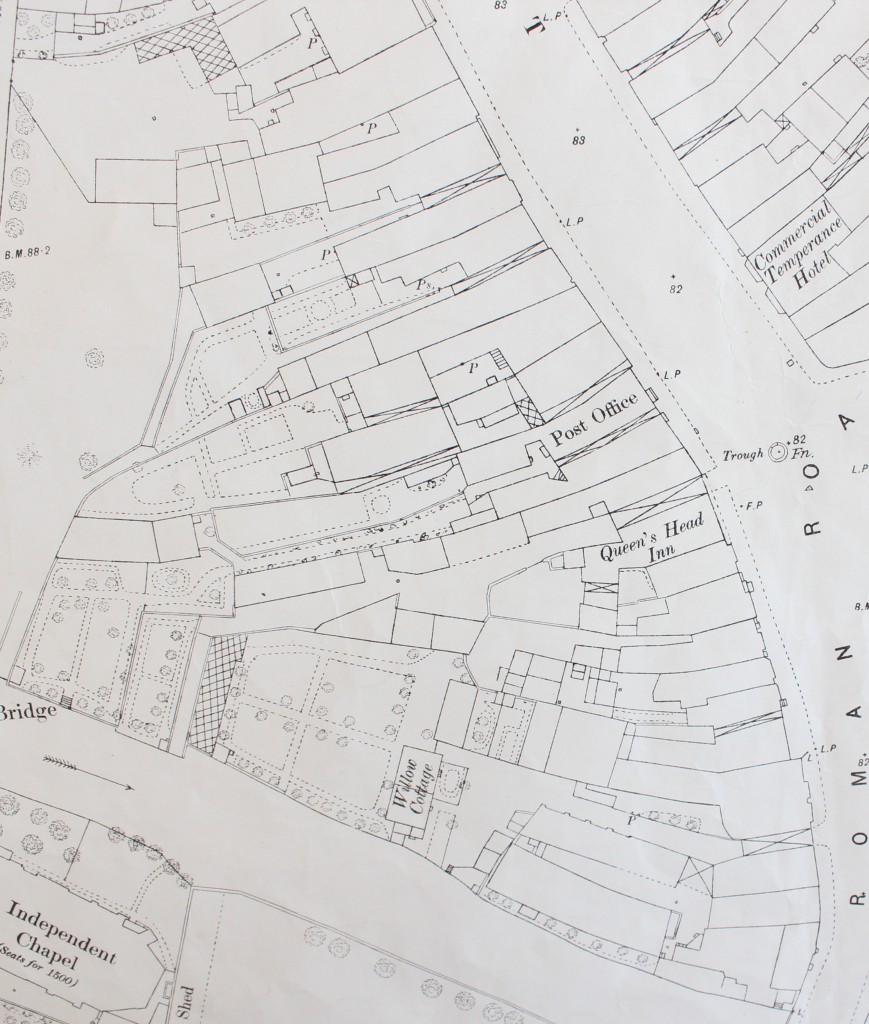

Observing the sites of 61-66 High Street on several Ordnance Survey maps, it was immediately obvious that a number of properties had been consolidated, demolished or rebuilt over time. Using the first edition OS map of 1876 as a starting point, it is clear that large, department sized stores were not yet a standard feature of the high street. Based on this map, we can see that properties in this section of the high street were small and packed closely together, perhaps the result of centuries of uncoordinated and sporadic development.

Extract from the 1876 first edition OS map, from the west side of the high street. 61 High Street is occupied by the Queen’s Head inn. Adjacent to the Queen’s Head sits a narrow passageway, which leads from the high street into the yard. To the north of the passageway is the site of 62 High Street and adjacent to that, a number of small, individual properties, all of which would ultimately form part of the Marks and Spencer’s site in the 1970s.

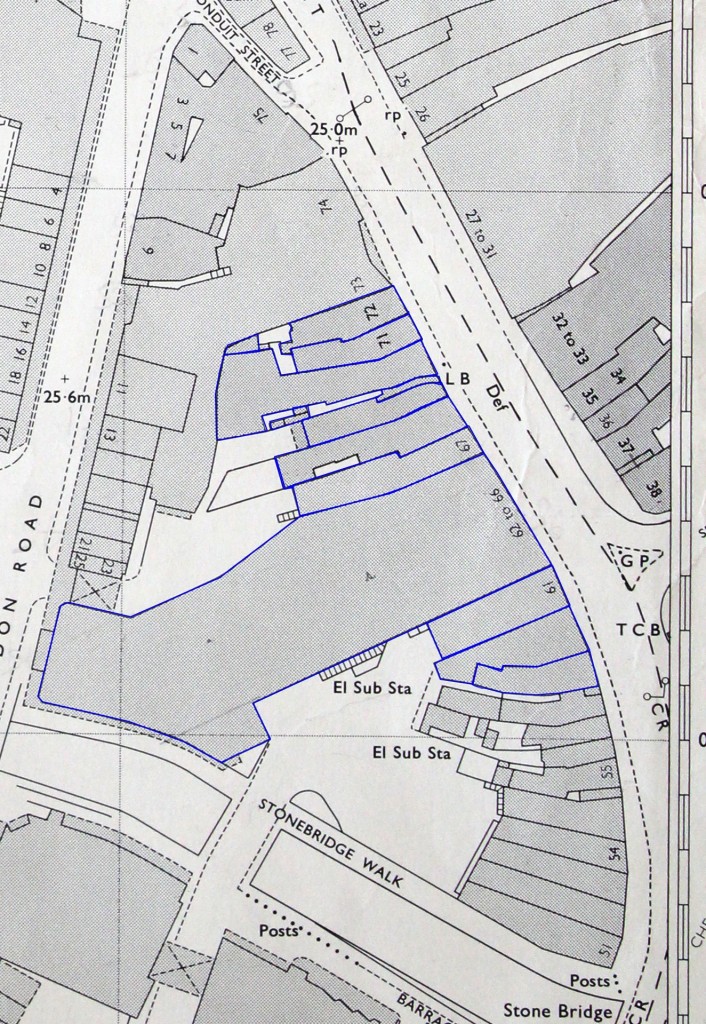

For a more direct comparison, we took photographs of the OS maps from 1963 and 1974 and uploaded them into Photoshop.

Extract from the OS Maps of 1963 and 1974 showing the sites of 61-66 High Street. The 1963 extract has been highlighted in red, while the 1974 extract has been highlighted in blue.

Extract from the OS Maps of 1963 and 1974 showing the sites of 61-66 High Street. The 1963 extract has been highlighted in red, while the 1974 extract has been highlighted in blue.

From there we layered the maps, drawing around the border of each property using different colours to make it easy to differentiate between them. Areas where the borders had shifted were then clearly visible, indicating where and when development had occurred.

Extract from the 1963 map highlighted in red, layered with the extract from the 1974 map highlighted in blue.

At first glance, the OS map of 1963 appears remarkably similar to the OS map of 1876. There are still plenty of small properties, packed closely together. The Queen’s Head is still present, identifiable by the ‘PH’ for public house. The property retains its distinctive shape and the narrow passageway, sandwiched between 61 and 62, is still visible.

The biggest and most obvious changes have occurred by the OS map of 1974. The 1974 map presents a significantly changed section of the high street. The former Queen’s Head building has been demolished, and in its place a uniform, rectangular building has been erected. The narrow passageway has been built over and now features as part of the sites of 61 and 62. The sites of 62-66 now form one large property, occupied by Marks and Spencer’s.

Photograph of the west side of the high street including the Queen’s Head in the centre and several properties to the right that would eventually form part of the Marks and Spencer’s site. Photo by Fred Spalding.

This map comparison perfectly illustrates how the town was transforming in the 20th century to accommodate modern development. In many cases the new buildings replaced small, dated properties which were considered no longer fit for purpose. The imperfect, quirky buildings visible in the Spalding photograph above were replaced by larger modern buildings built over several of the historic plots. Whether these new, spacious retail establishments improved the overall appearance of the high street is open to debate.

If you would like to use historic maps for a project of your own, do come and visit our Searchroom where staff will be happy to help you get started.

And that’s all from the Chelmsford Then and Now project! We will shortly be publishing the results of a similar project undertaken in Colchester so if you like old maps and historic photos there are more treasures to come.