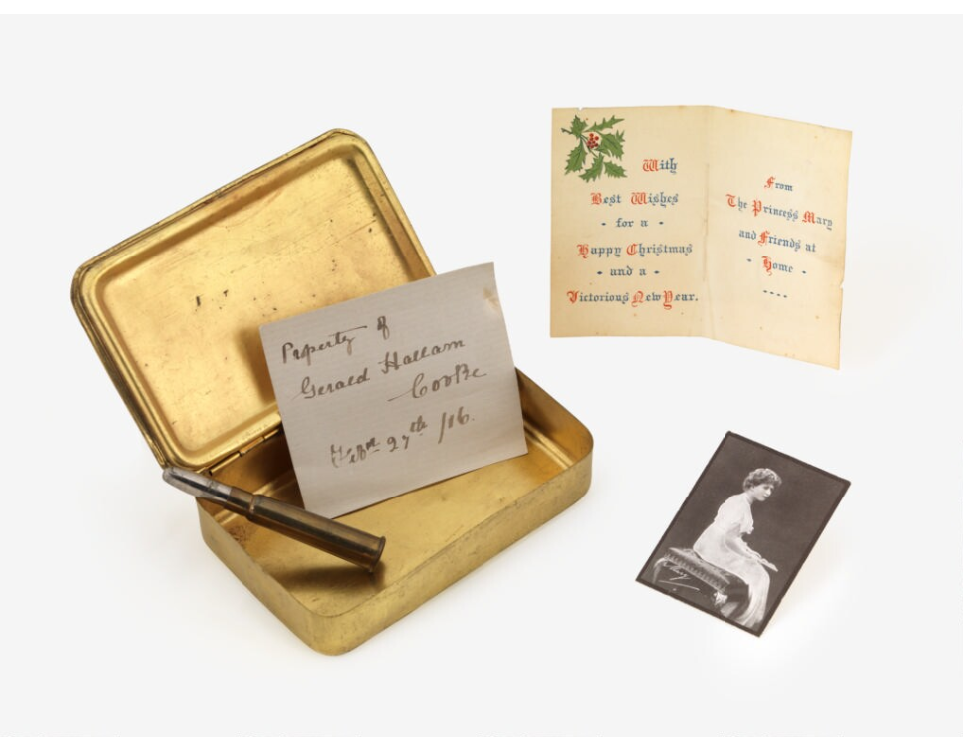

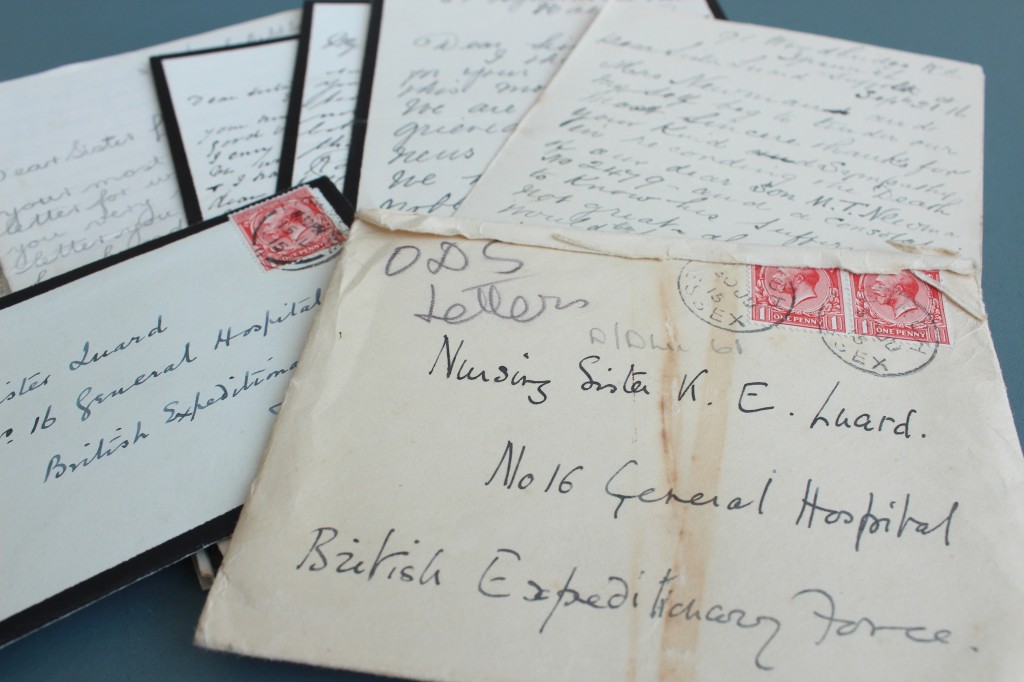

This post is published with thanks to Caroline Stevens, Kate Luard’s great-niece, who supplied the extracts from Unknown Warriors.

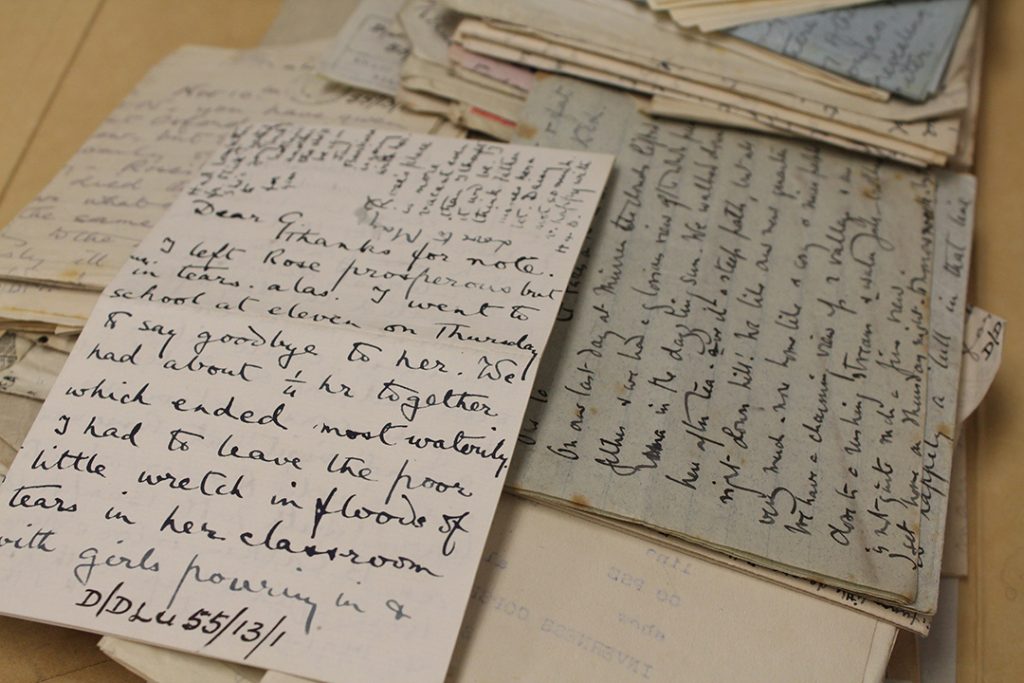

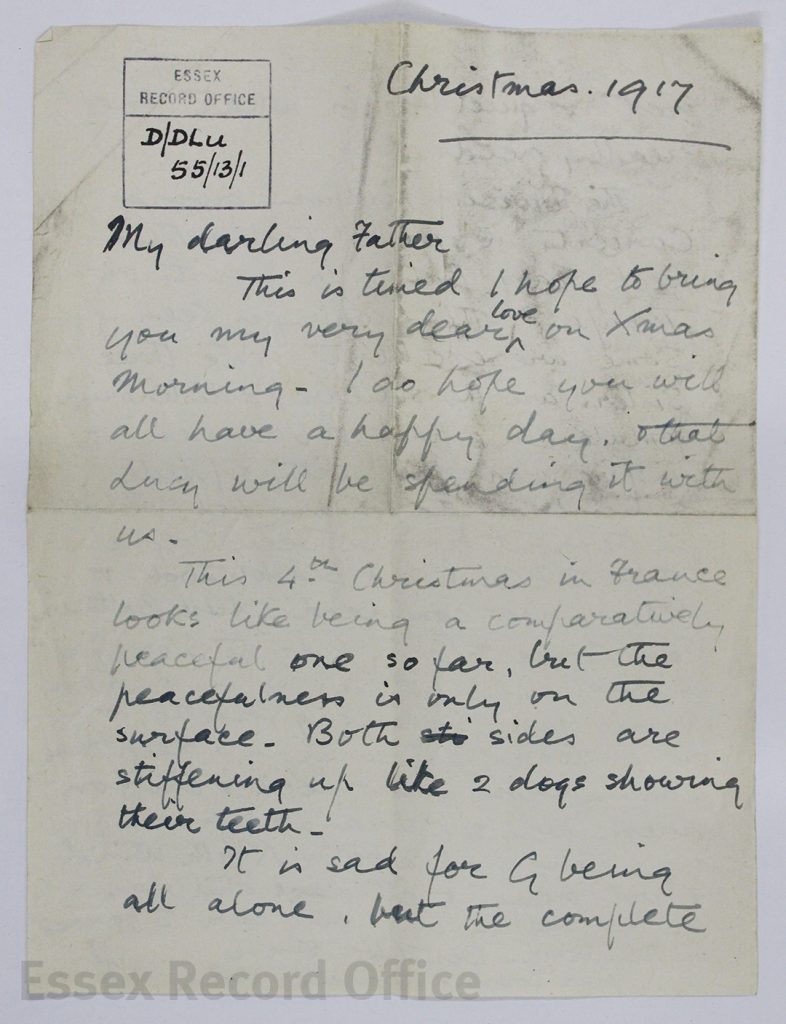

In spring 1918, the German army launched a series of attacks along the Western Front, advancing further than either side had since 1914. Nursing Sister Kate Luard, of Birch, near Colchester, was caught up in the Allied retreat, and wrote home about her experiences as the dramatic events unfolded (you can read more about her in our previous posts).

The Germans were attempting to defeat the Allies before the arrival of troops from the United States, and were able to reinforce their lines with troops freed up after the Russian surrender in late 1917.

During 1917, Kate had nursed behind the lines at the Battles of Arras and at Passchendaele. 1918 was to prove no less eventful for her.

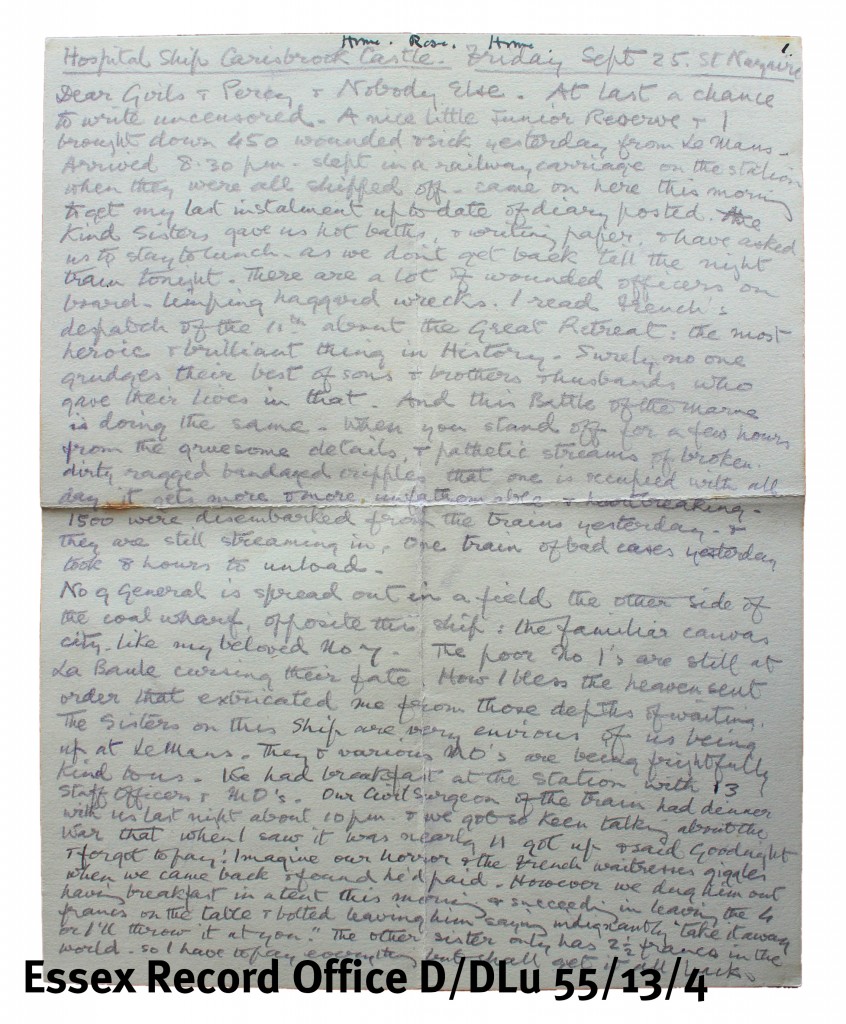

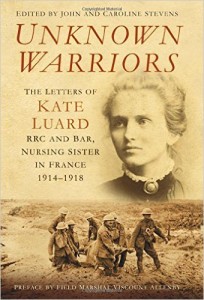

To help put the letters into a geographical context, the locations from which Kate wrote at this time are tracked in the map below. The letters quoted here are reproduced in Unknown Warriors: The Letters of Kate Luard, RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France, 1914-1918.

Preparations

The Allies were expecting a German advance. As part of the preparations, Kate received orders on 6 February to report to Marchélepot, in the most southern sector of the Somme area, to set up a new Casualty Clearing Station (CCS).

Wednesday, February 6th 1918. Abbeville

Orders came the day before yesterday to report here, and I find it is for my own Unit, at a place behind St Quentin – a line of country quite new to me. None of my old staff are coming but a new brood of chickens awaits me here and I take three up with me to-morrow. In a new Camp after a move there is nothing to eat out of and nothing to sit on, and it’s the dickens starting a Mess and equipping the Wards at once. They sent me all the 60 miles in a car.

Thursday, February 7th. Marchélepot, south of Péronne. 5th Army

We left Abbeville at 9 p.m. by train to Amiens and got there to find two Ambulances waiting for us. The rest of the run was through open wide country and all the horrors and desolation of the Somme ground, to this place – Marchélepot. There is a grotesque skeleton of a village just behind us, and you fall over barbed wire and in to shell-holes at every step if you walk without light after dark. There is no civil population for miles and miles; it is open grassland – a three years’ tangle of destruction and neglect. All the C.C.S.’s are in miles of desolation behind the lines.

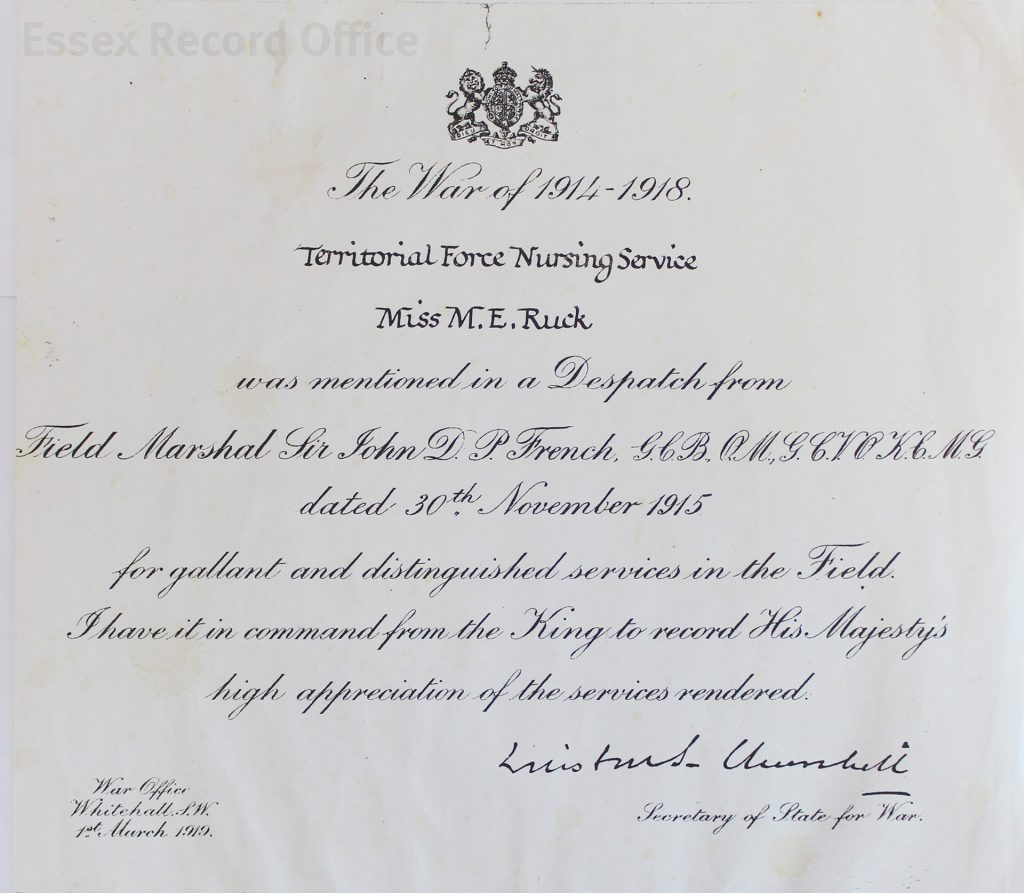

DESTRUCTION ON THE WESTERN FRONT, 1914-1918 (Q 61242) Ruins of the church at Marchelepot, 19 September 1917. It was abandoned by the Germans during their retreat to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205308701

The Colonel and the Officers’ Mess gave us a cheery welcome, and the orderlies are all beaming and looking very fit. I’m thankful that only three Sisters came with me as we found no kitchen, no food, no fire and only some empty Nissen huts, but the Sisters of the C.C.S. alongside have fed and warmed us … sleeping comfortably on our camp beds in one of the Nissen huts and shall have the kitchen started to-morrow. The Hospital has only been dug in since Sunday week – shell holes had to be filled in and grass cut before tents could be pitched or huts put up.

Saturday, February 16th

I expect you’re having about 20 degrees of frost as we are here. Everything in your hut at night, including your own cold body, freezes stiff as iron, but there is a grand sun by day and life is possible again. The patients seem to keep warm enough in the marquees with blankets, hot bottles and hot food, but it is a cold job looking after them.

Fritz has begun his familiar old games. Yesterday he bombed all round, but nothing on us. We are wondering how long our record of no casualties will stand: we are a tempting target, and have no large Red Cross on the ground, and no dug-outs, elephants [small dug-outs reinforced with corrugated iron] or sand bags.

This afternoon I went to Péronne. It was once a beautiful town with a particularly lovely Cathedral Church, white and spacious; only some walls and one row of pillars are left now. It is much more striking seeing a biggish town with its tall houses stripped open from the top floor downwards and the skeleton of the town empty, than even these poor villages, in rubbly heaps.

DESTRUCTION ON THE WESTERN FRONT, 1917-1918 (Q 81469) The Cathedral at Peronne in ruins, 1918. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205325839

Sunday, February 17th

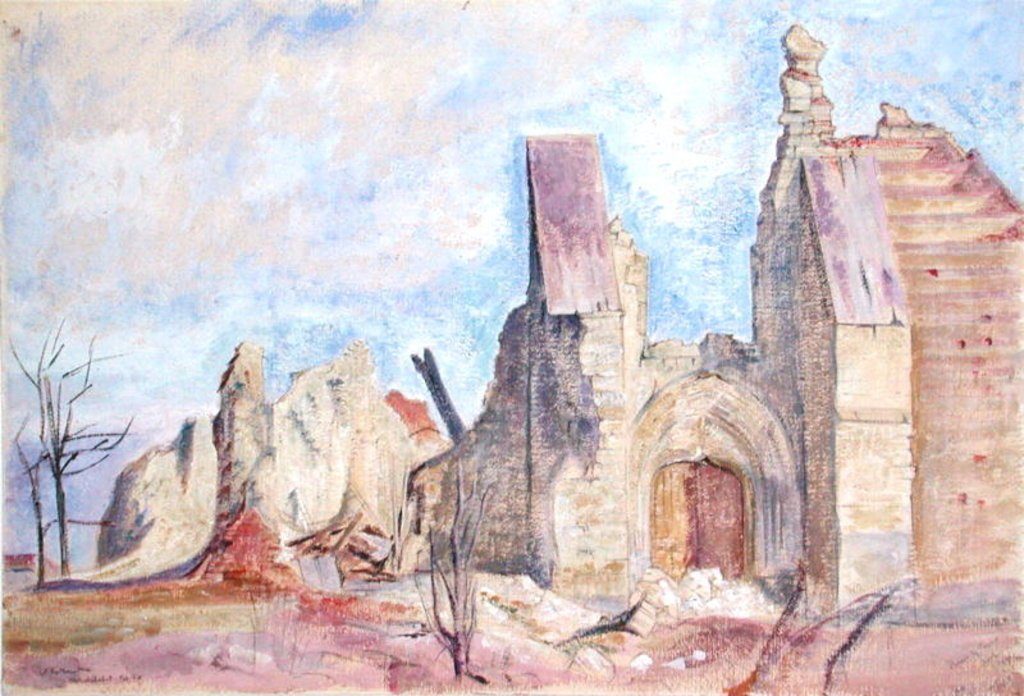

Terrific frost still. Drumfire blazing merrily East. I have been trying to draw these ruins. Nothing else of this 15th Century white stone church was visible from where I stood on a heap of bricks. It is quite like it [her sketch], especially the thin tottery bit on the right.

On the other side of my heap of bricks I then found an Official War Office artist [Sir William Rothenstein] drawing it too, and we made friends over the ruins and the War.

LMG209078 The West Front, Marchelepot Church (gouache on paper) by Rothenstein, Sir William (1872-1945); 26.8×53.3 cm; Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) U.K.; English, in copyright

PLEASE NOTE: The Bridgeman Art Library represents the copyright holder of this image and can arrange clearance.

Monday, February 25th

There is a cold rough gale on to-day, which is a test of our newly pitched Wards and of our tempers. Work is in full swing …. The Colonel knowing my passion for solitude has got me an Armstrong Hut as at Brandhoek and Warlencourt, instead of a quarter Nissen like the rest. It is lined with green canvas and has a wee coal stove and odds and ends of brown linoleum on the floor – all three luxuries I’ve never had before. It looks across the barbed wire and shell-holes straight on to the ruins and the Church.

A terrific bombardment began at 9.30 this evening. We have seen a good deal of Professor Rothenstein. He brought his drawings over to our mess to see.

February 28th

I suppose the newspaper men have long ago got the opening lines of their leaders ready with, “the long expected Battle Wave has rolled up and broken at last, and the Clash of two mighty Armies has begun” etc. etc. It may not be long until they can let it go. Yesterday the C.O.’s of C.C.S.’s of this Army were summoned to a Conference at the D.M.S.’s [Director of Medical Services] Office and given their parts to play. We have arranged accordingly and proceeded in all Departments to indent for Chloroform, Pyjamas, Blankets, Stretchers, Stoves, Hot Water Bottles and what not. The R.E. [Royal Engineers] are working rapidly; Nissen Huts springing up like mushrooms, electric light and water laid on, bath houses concreted, boilers going, duckboards down, and Reinforcements of all ranks arriving. A train is coming to clear the sick to-morrow.

Saturday, March 2nd

Nothing doing so far. Everyone is posted to his right station for Zero and meanwhile the usual routine carries on. To-day there is the most poisonous blizzard. The thin canvas walls of my wee hut are like brown paper in this weather, this violent icy wind blows the roof and walls apart and layers of North Pole and snow come knifing in …

Monday, March 4th

A mighty blizzard snowstorm has covered us and the Boche and there is nothing doing here. Later. the DMS has just been around again with more warnings; and consequently renewed preparations for Zero.

I’ve got some primroses growing in a blue pot, grubbed up out of a ruined garden before the snow. The only way of getting in to my Armstrong Hut at first was across a plank over a shell-hole. The R.E. are fortifying our quarters against bombs. We take in every other day and evacuate about every four days – almost entirely medical cases.

The attack

The German offensive began on 21 March 1918. An artillery bombardment began at 4.40am, covering a target area of 150 square miles. Over 1,100,000 shells were launched in five hours. On the first day, the Germans broke through the Allied lines in several places, and the British sustained over 7,500 deaths and 10,000 wounded. Within two days the British were in full retreat, including the Casualty Clearing Stations.

Friday, March 22nd

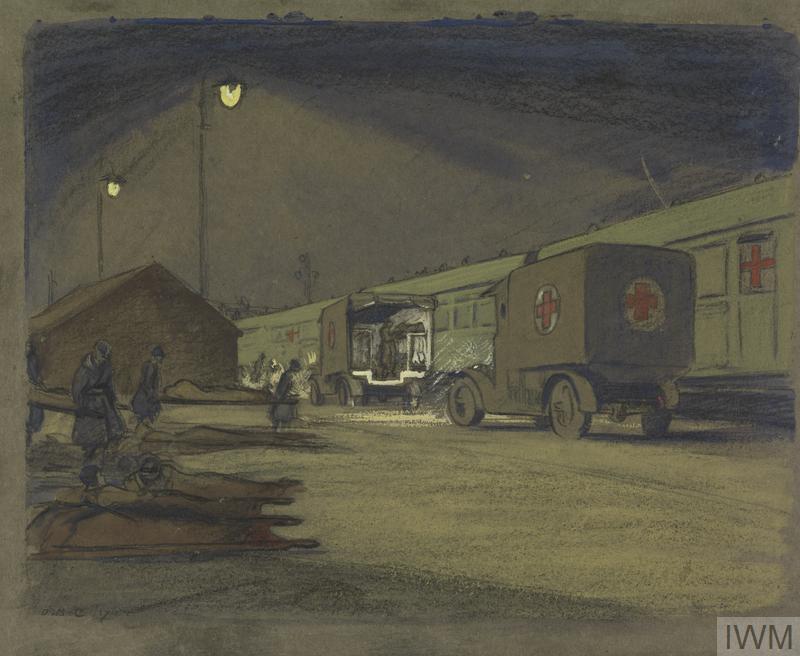

A ghastly uproar began yesterday, Thursday morning, March 21st. The guns bellowed and the earth shook. Fritz brought off his Zero like clockwork at 4.20 a.m. and in one second plunged our front line in a deluge of High Explosive, gas and smoke, assisted by a thick fog of white mist. Our gunners were temporarily knocked out by gas but soon recovered and gave them hell, which caught their first infantry rush, but they came on and advanced a mile. We suddenly became a front line C.C. S. and the arrival of the wreckage began, continued and has not ended. We began about 9.30 with our usual 14 Sisters and by midnight we numbered 40 as at Brandhoek. Only two Ambulance Trains have come to evacuate the wounded, and the filling up continues. The C.O. and I stayed up all night and to-day, and we have now got people into the 16-hours-on-and-8-off routine in the Theatre etc. We had 102 gassed men in one ward, but only 4 died. Ten girl chauffeurs drove up in the middle of the night with five Operating teams from the Base.

THE GERMAN SPRING OFFENSIVE, MARCH-JULY 1918 (Q 11586) Battle of Estaires. A line of British troops blinded by tear gas at an Advanced Dressing Station near Bethune, 10 April 1918. Each man has his hand on the shoulder of the man in front of him. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205193875

Friday night, 11 p.m.

Just off to bed after 40 hours full steam ahead. Everything and everybody is working at very high pressure and yet it makes little impression on the general ghastliness. This is very near the battle, and gets nearer; there are fires on the skyline and to-night bombs are dropping like apples on the country around. The artillery roar has been terrific to-day. Good-night.

Palm Sunday, March 24th, 9 a.m. Amiens

The night before last after writing to you, things looked a bit hot … and the map was altering every hour for the worse … ours was the place where they broke through and came on with their guns at a great pace. All the hot busy morning wind-up increased, and faces looked graver every hour. The guns came nearer, and soon Field Ambulances were behind us and Archies [anti-aircraft guns] cracking the sky with their noise. We stopped taking in because there were no Field Ambulances, and we stopped operating because it was obvious we must evacuate everybody living or dying, or all be made prisoners if anybody survived the shelling that was approaching. Telephone communication with the D.M.S. was more off than on, and roads were getting blocked for many miles, and the railway also. We had a 1000 patients until a train came in at 9 a.m. and took 300. Every ward was full and there were two lines of stretchers down the central duck-walk; we dressed them, fed them, propped them up, picked out the dying at intervals as the day went on, and waited for orders, trains, cars or lorries or anything that might turn up. At 10 a.m. the Colonel wanted me to get all my 40 Sisters away on the Ambulance Train, but as we had these hundreds of badly wounded, we decided to stay …

At mid-day the Matron-in-Chief turned up in her car from Abbeville and came to look out for her 80 Sisters – 40 with me and 40 at the other C.C.S. A made-up temporary train for wounded was expected, and we were to go on whichever Transport turned up first and scrap all our kit except hand-baggage. … the Resuscitation Ward was of course indescribable and the ward of penetrating chests was packed and dreadful. Some of the others died peacefully in the sun and were taken away and buried immediately.

At about 5 p.m. the Railway Transport Officer of the ruined village produced a train with 50 trucks of the 8 chevaux or 40 hommes pattern, and ran alongside the Camp; not enough of course for the wounded of both Hospitals but enough to make some impression. Never was a dirty old empty truck-train given a more eager welcome or greeted with more profound relief. The 150 walking cases were got into open trucks, and the stretchers quickly handed into the others, with an Orderly, a pail of water, feeders and other necessaries in each. One truck was for us, so I got a supply of morphia and hypodermics to use at the stoppages all down the train. Then orders came from the D.M.S. that Ambulance Cars were coming for us, so the Medical Officers took the morphia and most of our kit. There were 300 stretcher cases left but another train was coming for them. The Sister in charge of the other C.C.S. told me Rothenstein [Official War artist William Rothenstein whom Kate met when they were both sketching at Marchelepot was helping in the Wards like an orderly.

The Boche was 4 miles this side of Ham, just in to Péronne, and 3 miles from us – 13 miles nearer in 2½ days. I am glad I have seen Péronne. The 8th Warwicks marched in on March 19th 1917. The Germans will take down our notice board on March 23rd 1918 and put up theirs.

We got off in 4 Ambulance Cars escorted by three Motor Ambulance Convoy Officers. They had to take us some way round over battlefields and ghastly wrecked woods and villages, as he was shelling the usual road heavily between us and our destination (Amiens). We rook five hours getting there owing to the blocked state of the roads, with Divisions retreating and Divisions reinforcing, French refugees, and big guns being trundled into safety. He chose that evening to bomb Amiens for four hours.

Sunday, March 24th

The Stationary Hospital people here (Amiens) were extraordinarily kind and gave us each a stretcher, a blanket and a stretcher-pillow in an empty hut. They had not the remotest idea they would be on the run themselves in a day or two.

Monday, March 25th. 10.30 p.m. Abbeville.

It is in Orders that no one may write any details of these few days home yet, so I am keeping this to send home later, but writing it up when I can.

Yesterday afternoon I dug out Colonel Thurston, A.D.M.S. Lines of Communication, and asked him for transport from Amiens to Abbeville. On the Station was a seething mass of British soldiers and French refugees. The Colonel had brought the last 300 stretcher cases down the evening before in open trucks with all the M.O.s [Medical Officers] and personnel. Our wounded were lying in rows along the platform with our Orderlies; they had been in the trucks all night and all day. Some had died; the Padre was burying the others in a field with a sort of running funeral, up to the time they left. They were taken straight to their graves as they died. Now our C.C.S. has no equipment, we shall all, C.O.s, M.O.s, Sisters and men, be used elsewhere.

Wednesday night, 27th

Yesterday I was sent up to No.2 Stationary Hospital [in Abbeville] to do Assistant Matron by Miss McCarthy [Matron in Chief] and we’ve had a busy day, admitting and evacuating.

Saturday, Easter Eve, March 30th 1918.

Yesterday evening Miss McCarthy turned me into a Railway Transport Officer at the Railway Station, and it is the most absolutely godless job you could have. You must have command of a) the French language, b) your temper, c) any number of Sisters and V.A.D.s, d) every French porter you can threaten or bribe, e) the distracted R.T.O. and his clerks.

No mail has reached me since we cleared out this day week; do write soon to No.2 Stationary Hospital. I am quite fit.

Easter Monday, April 1st

It has been a dazzling spring day after the heavy rain – spent as usual at the Station – not as R.T.O. this time but as A.M.F.O. (Army Military Forwarding Officer). The day after I last wrote to you, I had a 24 hours’ shift of R.T.O. … puddling about the platforms in the cold and wet. There are no waiting rooms, and the place was a seething mass of refugee families, and French soldiers and my herds of Sisters and kits. But they all got safely landed in their right trains and no kit lost.

Easter Tuesday

Had a very busy day at Triage as A.M.F.O. with my fatigue party fetching and loading kit. And a message came through from Miss McCarthy this evening – was I ready and fit for another C.C.S.? The answer was in the Affirmative.

Wednesday, April 3rd

Letters at last, joy of joys. The Times man is right … and it is all the things he has to leave out of his accounts, the little things officers and men from the Line tell us, that would show you why. And there are weeks of strain ahead …

Saturday night, April 6th

All your letters of the first day of the Battle are coming in. I didn’t quite realise you’d be really worrying. It came so suddenly, and running the wounded and the Sisters gave one no time at all to think – I couldn’t have let you know any sooner. We are plunged in work just now. Every available man has had to be put into the Wards – all the Clerks, Assistant Matron – everyone but the Cook and mess V.A.D.s. I am running two ramping Wards and everyone else is at full stretch. R.T.O. and A.M.F.O. are finished for the time being. All these three Hospitals are understaffed just now and are doing C.C.S. work. We get the men practically straight out of action …

Friday, April 12th. Namps

Orders came for me on Wednesday to take over this C.C.S. [No.41] at Namps. It is an absolutely divine spot, south of Amiens. The village is on a winding road, with a heavenly view of hills and woods, which are carpeted with blue violets and periwinkles and cowslips, and starry with anemones. The blue of the French troops in fields and roads adds to the dazzling picture but inside the tents are rows of ‘multiples’ and abdominals, and heads and moribunds, and teams working day and night in the Theatre, to the sound of frequent terrific bombardments. It has never been so incongruously lovely all round.

THE GERMAN SPRING OFFENSIVE, MARCH-JULY 1918 (Q 10932) Actions of Villers-Bretonneux. Wounded German prisoners at a Casualty Clearing Station at Namps, 26 April 1918. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205246573

This is the place where four derelict Casualty Clearing Stations amalgamated and got to work during the Retreat, without Sisters. Now it is run as one with a huge collection of Medical Officers and Orderlies and Chaplains from Units out of action, and with odds and ends of saved equipment. It is still very primitive with no huts and no duckboards and only stretchers, with not many actual beds, but it is quite workable.

The patients are evacuated as quickly as possible, and the worst ones remain to be nursed here. Of course, the rows of wooden crosses are growing rather appalling, but some lives are being saved.

We live four in a marquee in a field below the road and have daisies growing under our beds, no tarpaulins or boards. I’ve acquired a tin basin and a foot of board on two petrol tins for a wash-stand and am quite comfortable. Our compound has five marquees. French Gunners stray in and sleep on the grass all round us, and a constant stream of Poilus [French WW1 infantrymen] passes up and down the road. It is very noisy at night. The Cathedral has had two shells in it.

We live on boiled mutton every day twice a day: tea, bacon, bread and margarine in ample quantities does the rest. Our Mess Cookhouse is four props and some strips of canvas; three dixies, boiling over a heap of slack between empty petrol tins, is the Kitchen Range, in the open. We get a grand supply of hot water from two Sawyer boilers under the tree. The French village does our laundry.

Sunday, April 14th

He [the Germans] is at Merville, and what next I wonder? Here we are holding him all right, but each night of uproar one wonders when we’ll next be on the road again. The weather has changed and the dry, sunny valley has become a chilly, windy quagmire. There are no fires anywhere and very little oil for the lamps; it is very difficult to keep the men warm, and the crop of wooden crosses grows daily.

April 22nd

We are on the move again. The patients left to-day and the tents are down this evening. I expect we shall go to Abbeville, while they dig themselves in at the new site North of Amiens. Everything is very quiet here, except occasional violent artillery duels and bomb dropping at night.

Tuesday, 23rd

A month since we up and ran away from Jerry. It is Abbeville, and we are sitting on our kit waiting for transport. I wonder how black it looked in England on Saturday week, when Haig said “We have our backs to the wall” – worse than close to, probably.

______________________________________________________________________

Kate remained on the Western Front to the end all the way through to the end of the War. You can read more of her letters in Unknown Warriors: the letters of Kate Luard RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918.

Kate remained on the Western Front to the end all the way through to the end of the War. You can read more of her letters in Unknown Warriors: the letters of Kate Luard RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918.

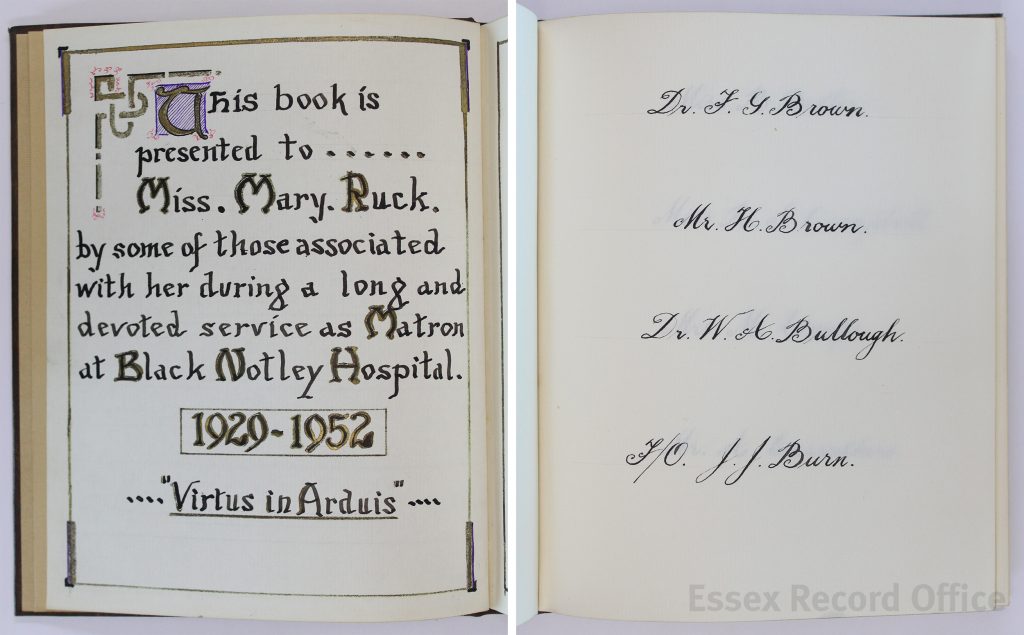

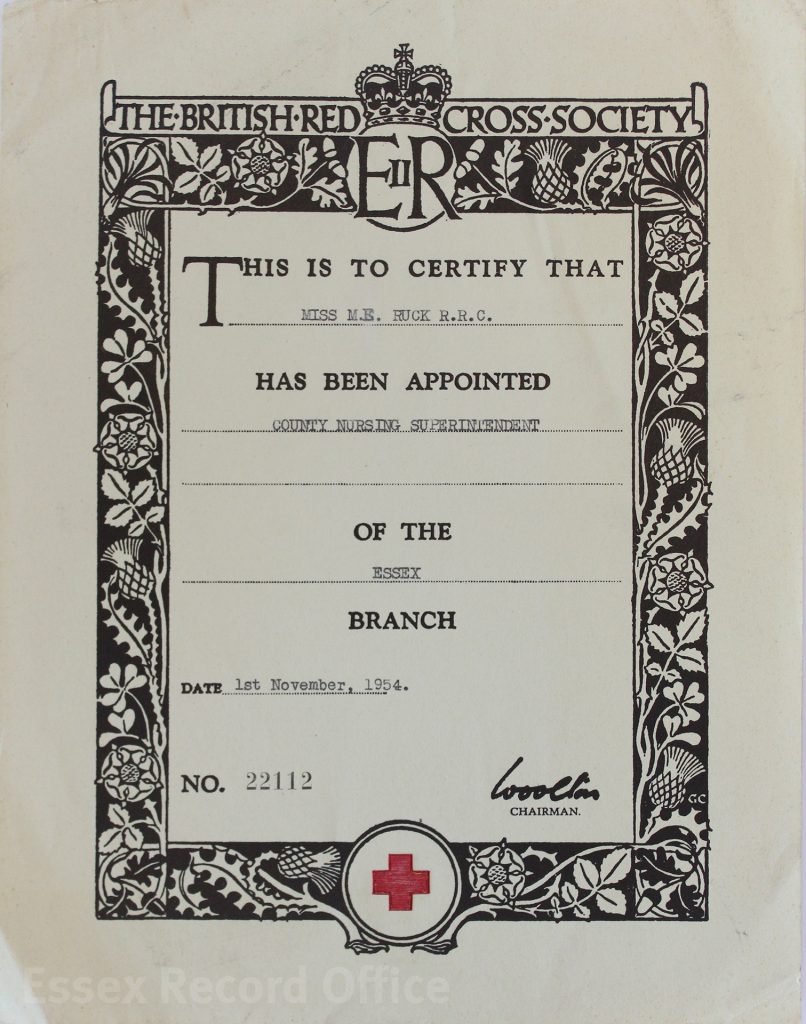

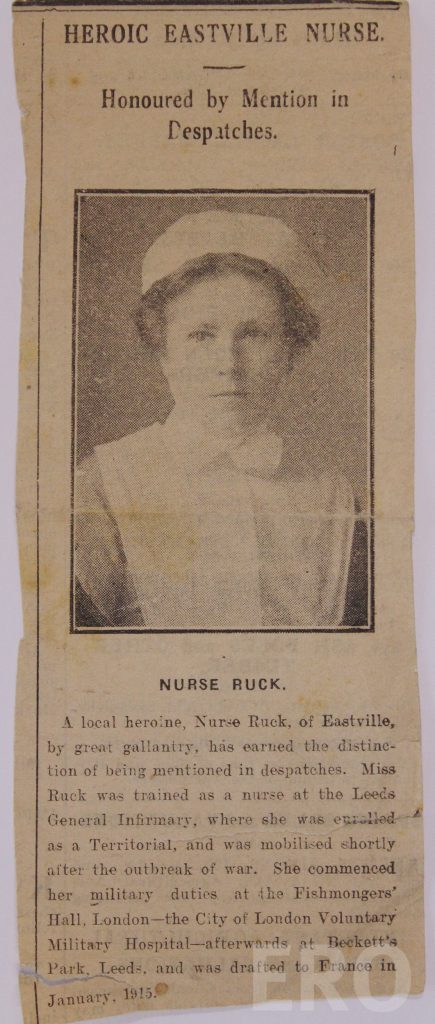

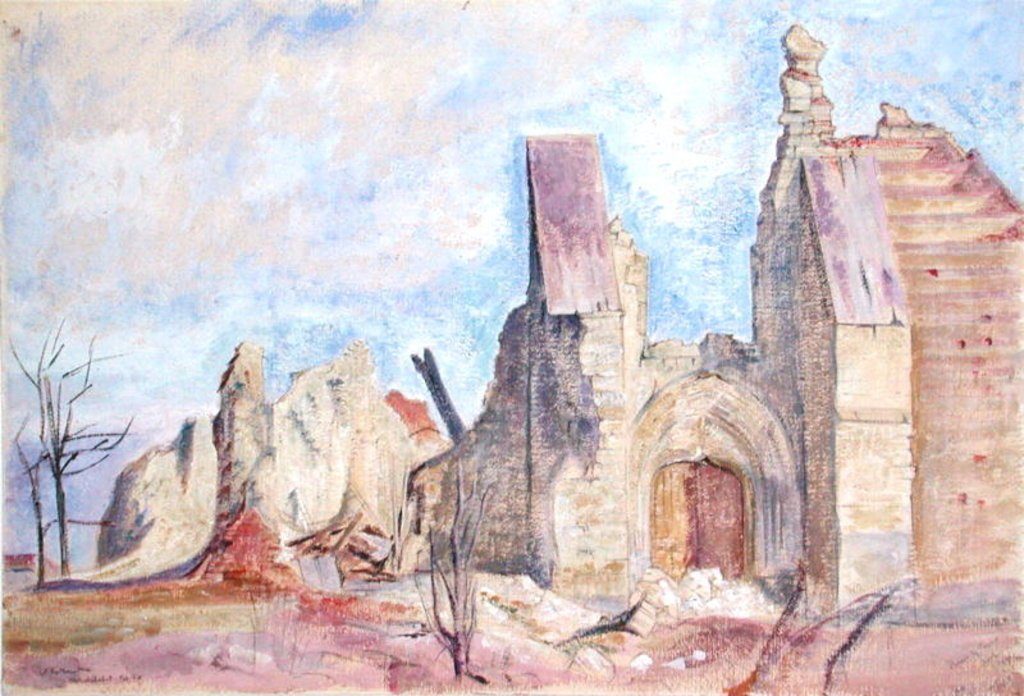

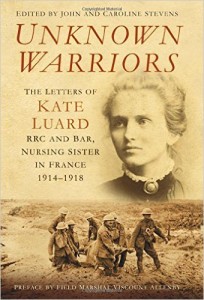

To celebrate International Nurses Day (marked each year on 12th May, Florence Nightingale’s birthday), we thought we’d take a look at the career of an eminent Essex nurse, Mary Ellen Ruck RRC, who served as the Matron of Black Notley Hospital near Braintree from 1929 to 1952.

To celebrate International Nurses Day (marked each year on 12th May, Florence Nightingale’s birthday), we thought we’d take a look at the career of an eminent Essex nurse, Mary Ellen Ruck RRC, who served as the Matron of Black Notley Hospital near Braintree from 1929 to 1952.

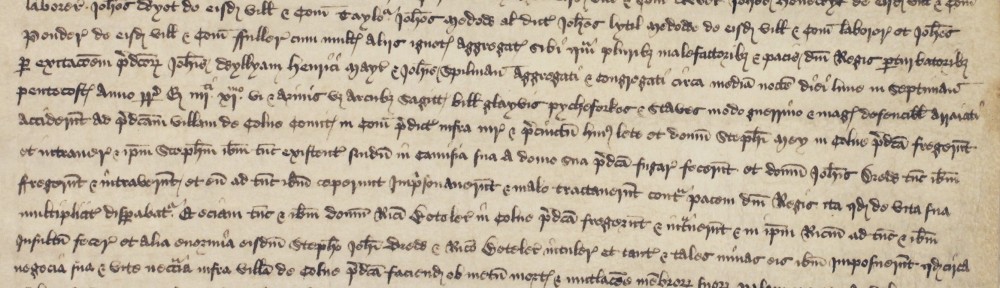

On the Main Line and the Goods Siding

On the Main Line and the Goods Siding

Kate remained on the Western Front to the end all the way through to the end of the War. You can read more of her letters in

Kate remained on the Western Front to the end all the way through to the end of the War. You can read more of her letters in