Today’s post from our medieval specialist Katharine Schofield is all about the importance of archery in medieval England. Join us to find out more with the English Warbow Society at Essex at Agincourt on Saturday 31 October 2015. This is a joint event with the Essex branch of the Historical Association, and all the details can be found here.

The use of longbows by the English archers was perhaps one of the most significant developments of the Hundred Years’ War and indeed of medieval warfare. The longbow had a decisive and devastating effect in the English victories at the Battles of Sluys in 1340, Crécy in 1346, Poitiers in 1356 and Agincourt in 1415.

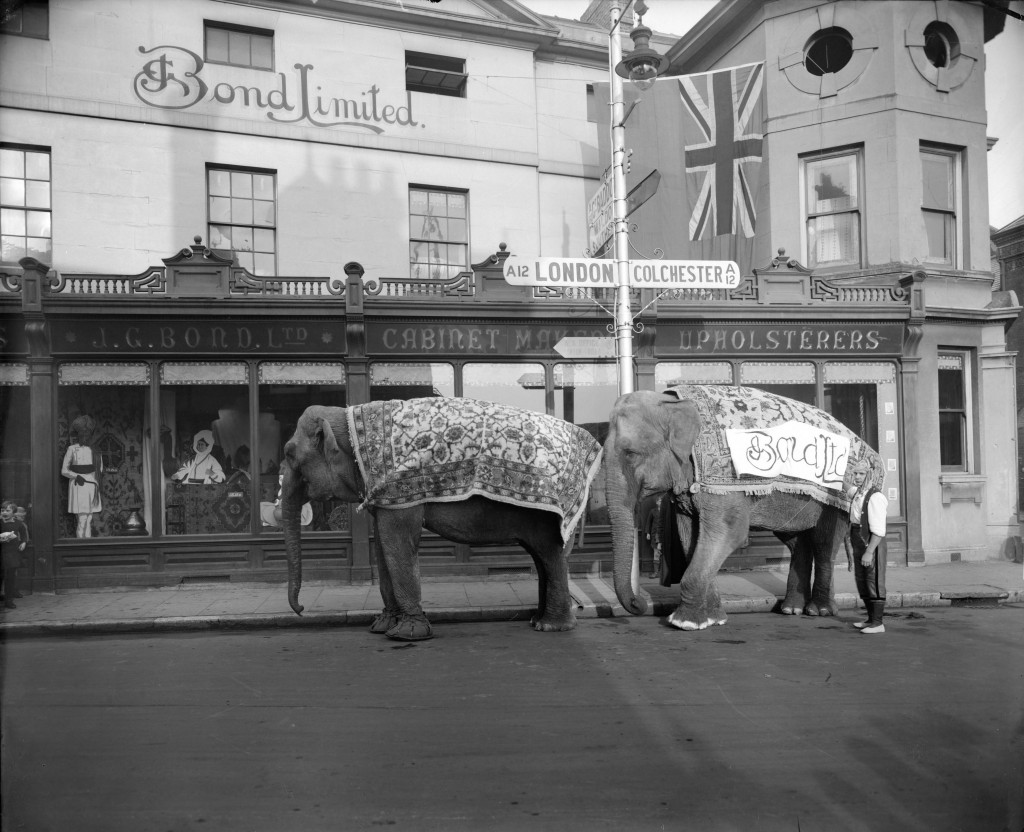

Ian Coote of the English Warbow Society using a traditional English warbow. See replicas of period bows and arrows and hear more about how significant their role was in the Hundred Years’ War at Essex at Agincourt

Photo: Chris Morris

The longbow originated in Wales and was used against the English in the 12th and 13th century invasions. A 12th century chronicler Gerald of Wales described how an Englishman was struck by a Welsh archer:

It went right through his thigh, high up, where it was protected inside and outside the leg by his iron cuirasses and then through the seat of his leather tunic; next it penetrated … the saddle … seat; and finally it lodged in his horse, driving so deep that it killed the animal.

The deadly effect of the longbow meant that it was soon incorporated into English forces. Longbows ranged in size from 5 to 7 feet [1.5 – 2.1 metres] and were usually made from yew, but wood from ash, elm and other trees could also be used. An archer could shoot over half a mile and could knock a knight off his horse. Archers could fire up to 12 arrows a minute, but would usually average about six arrows. The arrows were around 3 feet long with a tip designed to break through chain mail.

Archery was a necessary skill for all Englishmen from the 13th to the 16th century, when it was gradually superseded by more modern weapons of war. In 1181 the Assize of Arms did not mention bows and arrows, although a law of Henry I (1100-1135) stated that if a man was accidentally killed by an archer at practice then the archer could not be prosecuted for murder or manslaughter.

Archery practice remained a source of potential danger. The Essex Assizes held in August 1579 recorded the indictment of John Pollyn of Little Oakley who on 28 June with other young men at the butts in the parish had shot Thomas Downes, aged 16, in the left eye leaving him with a wound 3 inches deep of which he died the following day. In 1581 an inquest at Barking on Henry Fawcett, aged 19 recorded that a fisherman John Redforde accidentally shot Fawcett on the right side of his head to the depth of an inch while he was standing near the butts. Fawcett died from the wound a week later. The cause of death was recorded as ‘By misfortune’ [misadventure].

In 1252 another Assize of Arms was issued and this required every able-bodied man aged 15-60 to equip themselves with bows and arrows. This was not formally repealed until 1623/4. A declaration of 1363 acknowledged the successes that the longbow had brought:

Whereas the people of our realm, rich and poor alike, were accustomed formerly in their games to practise archery – whence by God’s help, it is well known that high honour and profit came to our realm, and no small advantage to ourselves in our warlike enterprises … that every man in the same country, if he be able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows … and so learn and practise archery.

In 1388 an Act required that all servants and labourers were to have bows and practice on Sundays and holidays.

By the 15th century archery was still considered to be of such importance that legislation was introduced to ensure that the equipment was readily available. An Act of 1472 required every merchant importing goods to bring in four bowstaves for every ton; in 1483-1484 ten ‘good’ bowstaves had to be imported for every butt of wine. Customs duty was removed from bow staves longer than 6 feet in 1503. Maximum prices for bows made of yew were fixed at 3s. 4d. in 1482/3.

In 1542 an Act of Parliament laid down rules for regular practice. It established a minimum distance of 220 yards (more than 200 metres) that men over 24 should be able to hit the target. It also prohibited houses for ‘unlawful games’ which prevented practice and the Quarter Sessions rolls for Essex record many prosecutions.

In 1574 the records of Colchester Borough contain a copy of an order to the bailiffs by Thomas Worrell, fletcher, and John Gamage, bowyer, who had been appointed as deputies by the Essex Commissioners. Lists were required of every householder, children and manservant aged 7-60 and they were required to muster before Worrell and Gamage on 5 May 1574 ‘with such bows and arrows as they ought to use’. Colchester’s records notes the letter ‘was not received until 10 p.m. on 3 May and therefore the muster was not carried out’ (D/B 5 R7 f.183r. – 184r.].

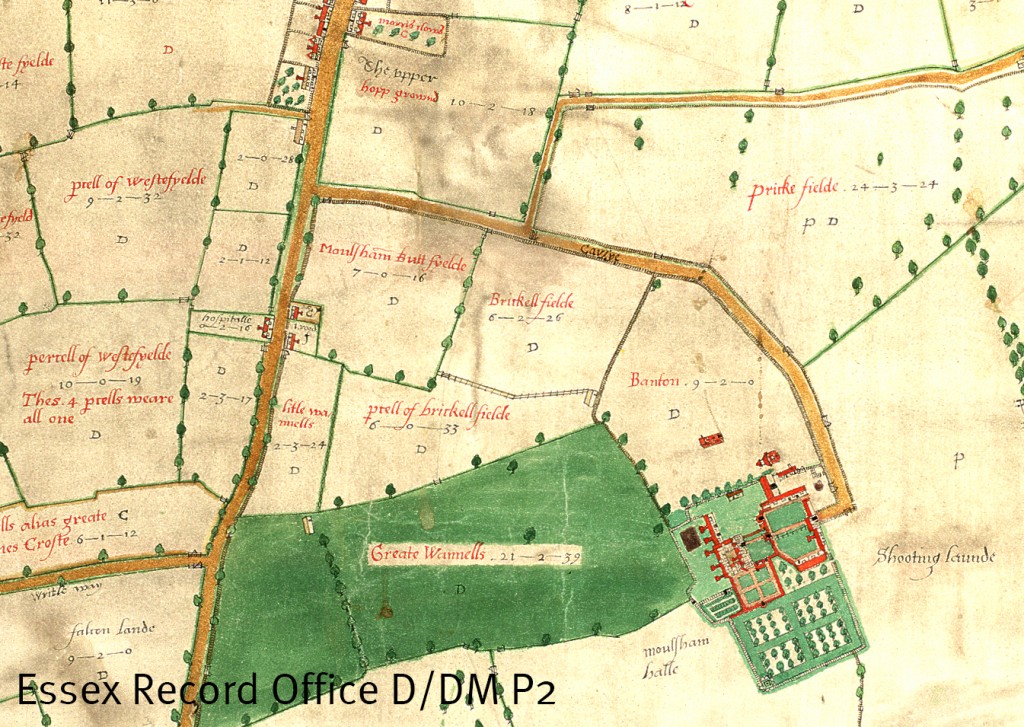

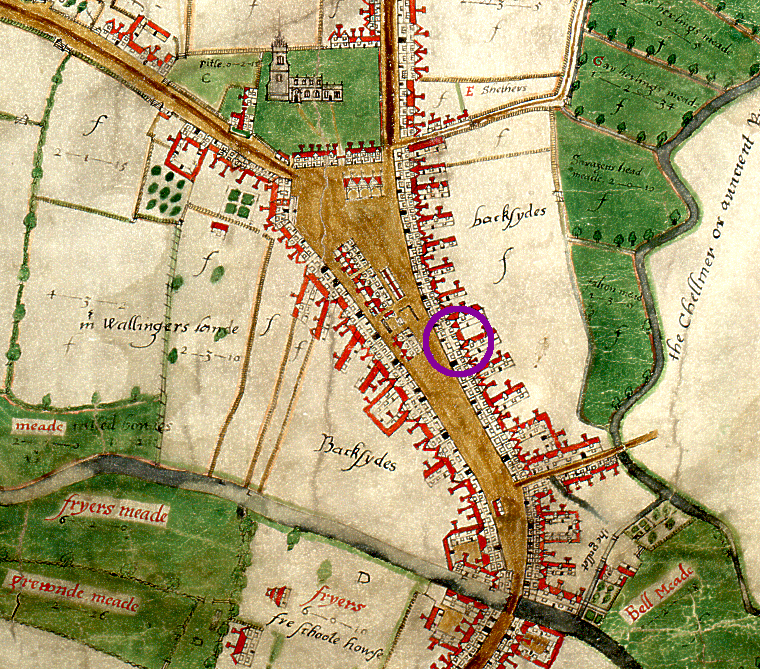

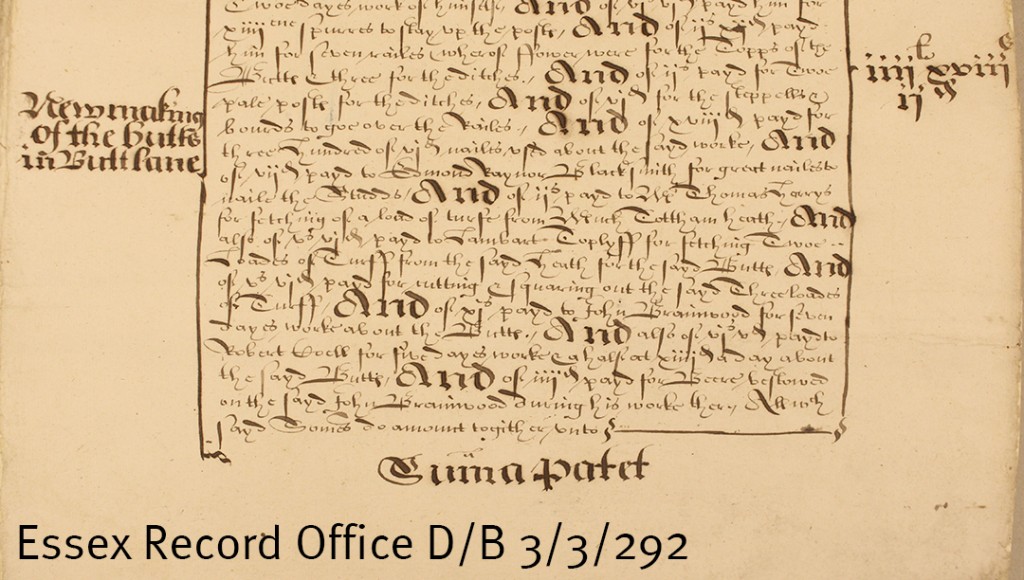

Every town and village would have had archery butts for practice. Butt Lane in Colchester is said to take its name from the fact that it led to the town’s butts. In Chelmsford the butts were located in Butt Field off Duke Street in the area covered today by Townfield Street and the railway station. As late as 1622 the chamberlains’ accounts for Maldon record the expenses in making new butts for the borough in Butt Lane (D/B 3/3/292).

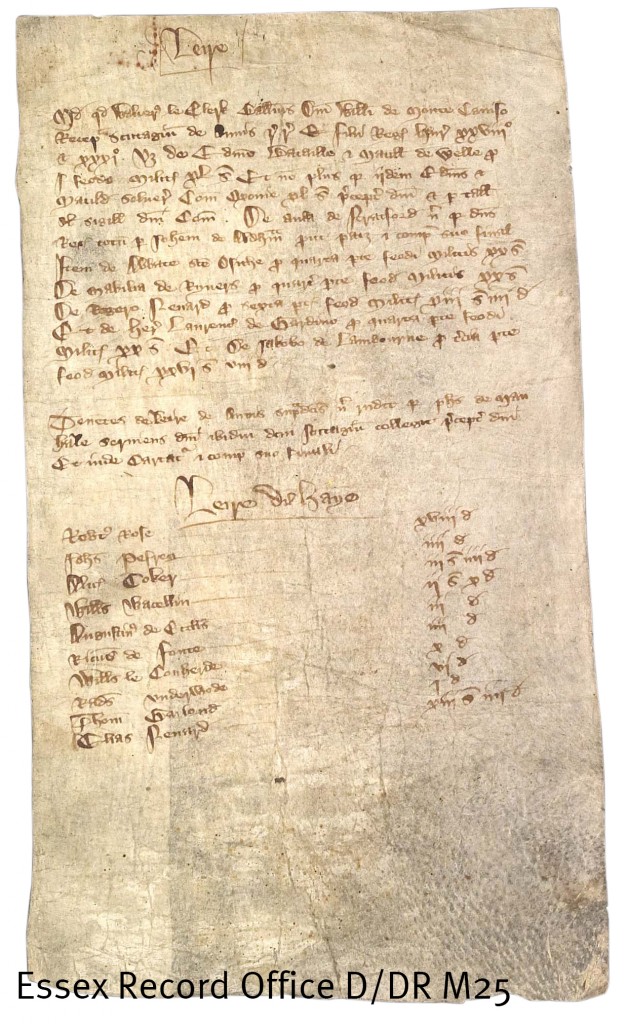

Extract from chamberlains’ accounts for Maldon recording the expenses of making new butts for the borough in Butt Lane, 1622 (D/B 3/3/292)

The records of Quarter Sessions for Essex have many examples in the 1560s, 1570s and 1580s of parishes throughout the county being reported for the butts being out of repair. Widford was reported at the Michaelmas 1572, Easter 1574, Epiphany and Midsummer 1575 and Easter 1584 Sessions, on the last occasion they had until Midsummer to repair them or pay a 5s. fine. Little Waltham was reported in 1572 and 1577 and Willingale Spain in 1574, 1575 and 1580. The lord of the manor and tenants of Grays Thurrock were presented in 1580 for ‘lack of butts in a convenient place’.

It was quite common for parishes to be given until the next Sessions (three months) to repair the butts or face a fine. Aveley faced a fine of 13s. 4d. in 1566, North Ockendon a fine of 6s. 8d. in 1576 and Little Canfield 12d. in 1580. In Danbury in 1574 it was reported that the butts were in decay and that Ambrose Madson had taken down one for his gaming there. While failure to maintain and repair the butts was commonly the issue, it was reported to the Michaelmas Sessions of 1568 by the jury for the Hinckford Hundred in the north of Essex that ‘our buttes be in good reprassyons’ (Q/SR 27/16)

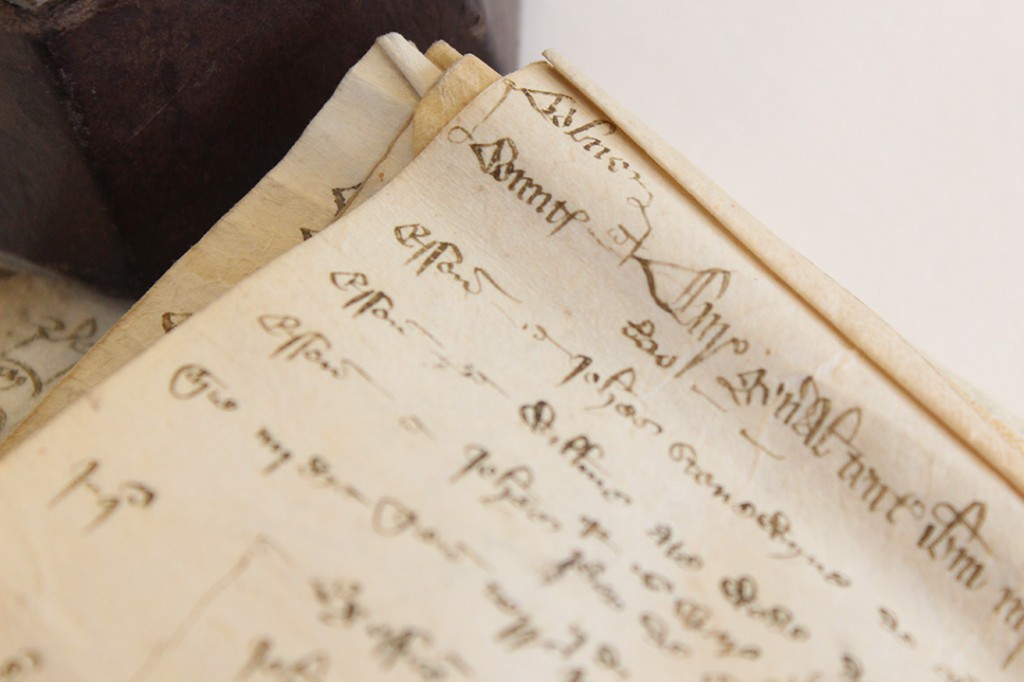

Given the requirements of the law, it is not surprising that there are a number of wills with bequests of bows and arrows. In 1529 John Archare of Maldon, currier bequeathed his best, second and third bows (D/ABW 1/5); and in 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada, George Ardlye of Weeley, husbandman left his bow and arrows to his son Robert. As late as 1612 Richard Crowe, a miller of Springfield left his bow and arrows to John Gibbs of Great Baddow.

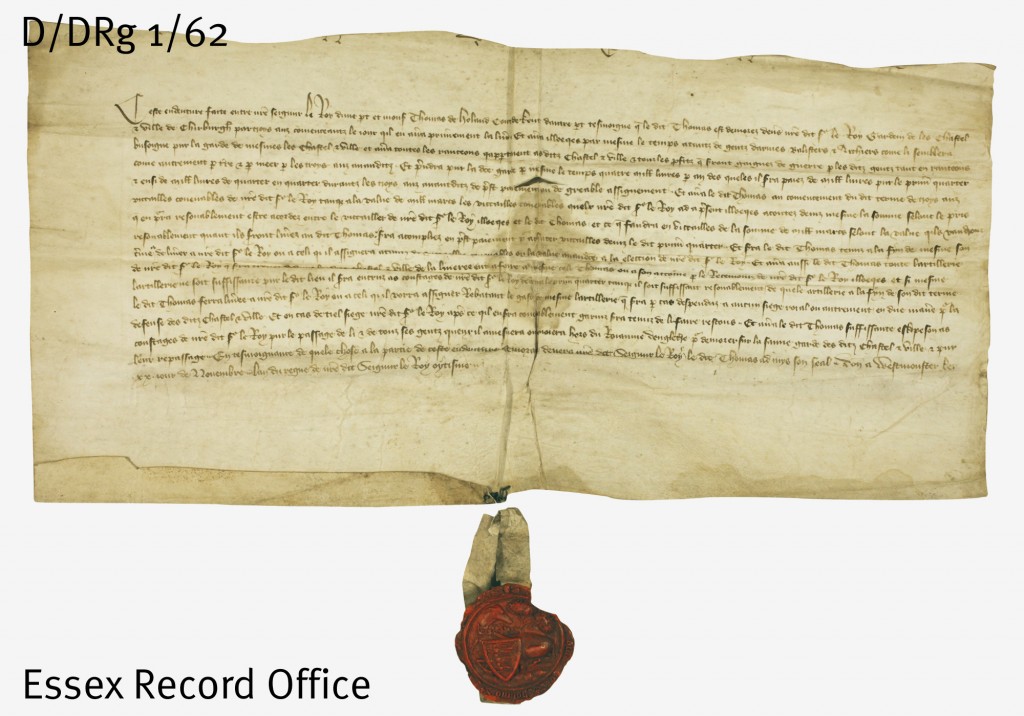

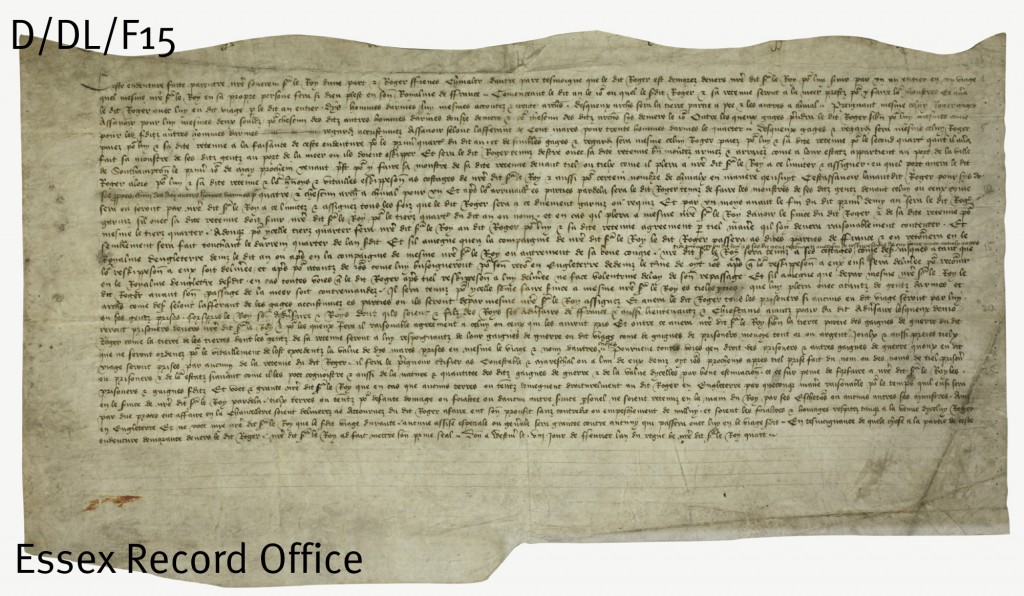

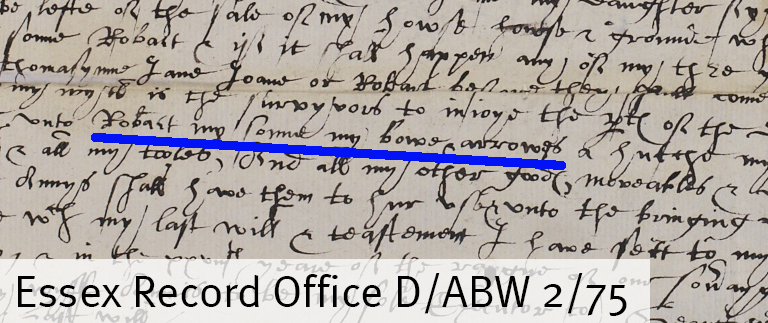

Extract from will of George Ardlye of Weeley, leaving his bow and arrows to his son Robert, 1588 (D/ABW 2/75)

By the end of the 16th century, although Quarter Sessions records have many examples of parishes and manors being prosecuted for their failure to maintain their butts, the longbow was gradually being replaced with firearms.

To find out more about medieval archery from the English Warbow Society, join us on 31 October 2015 for Essex at Agincourt; all the details of the day are here.