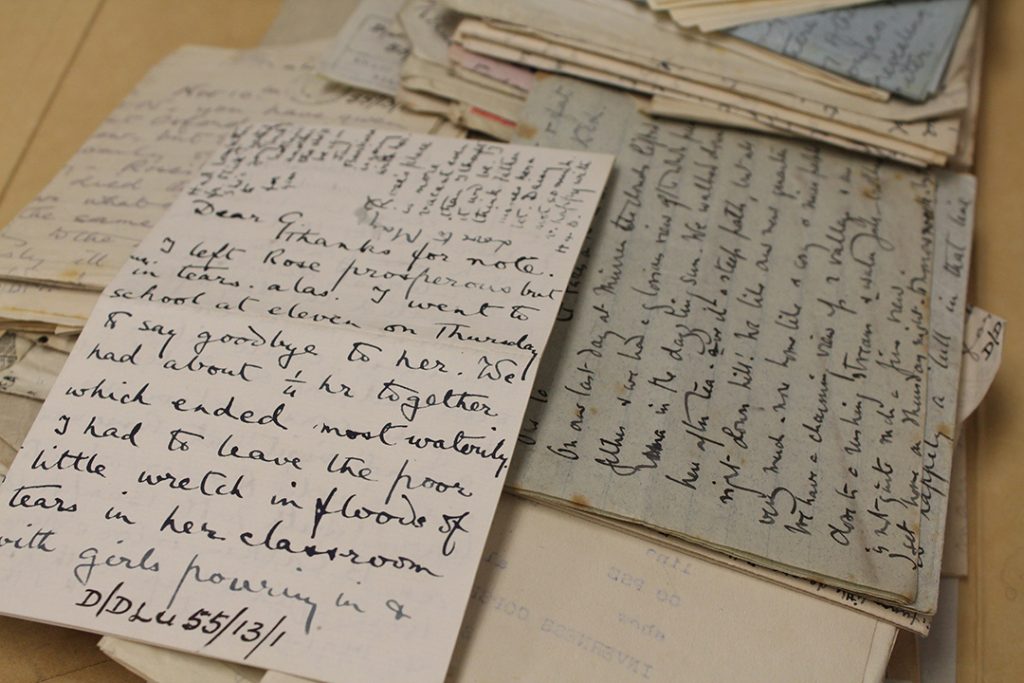

With thanks to Tim Luard

We all hope to spend Christmas having an enjoyable time with family and friends but, of course, that is not always to be.

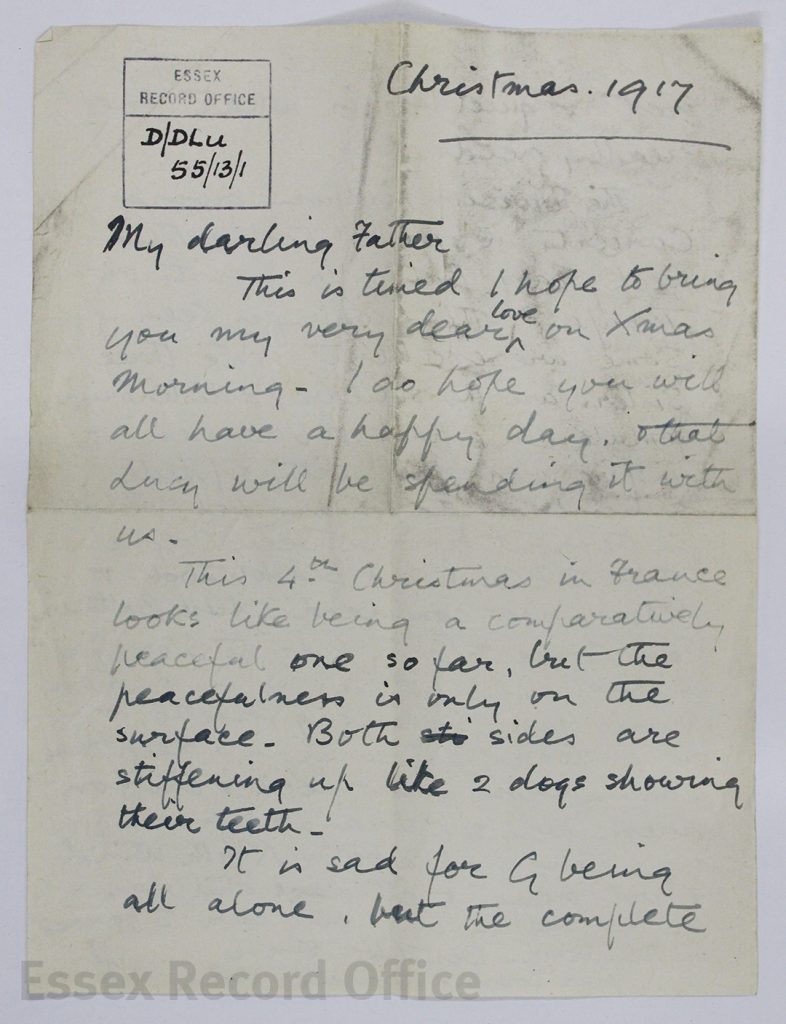

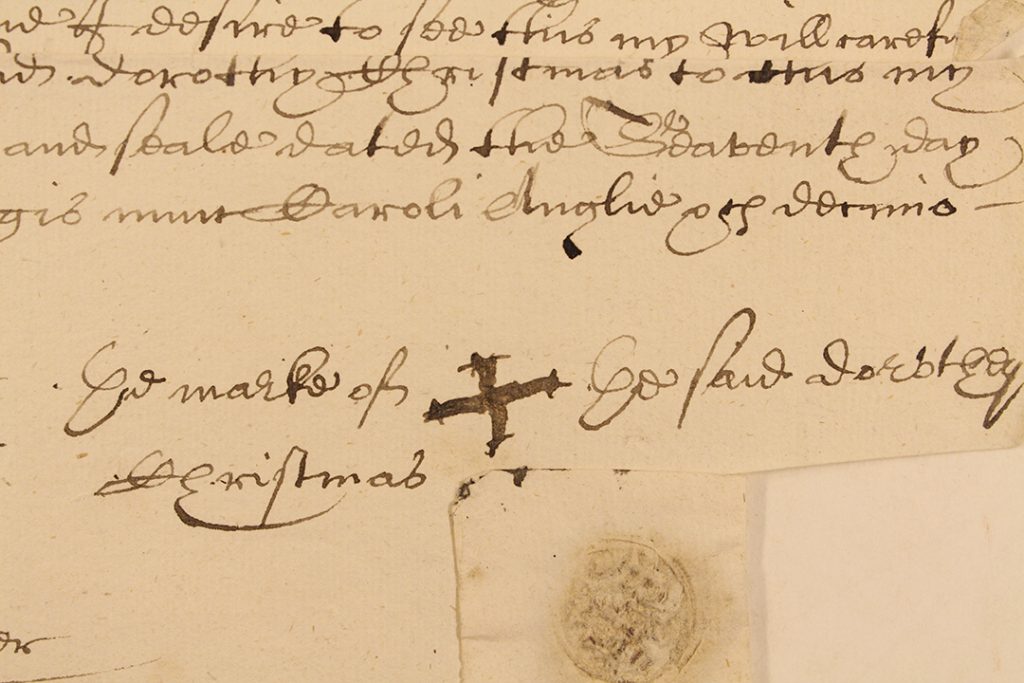

100 years ago, millions of people were away from home, swept up in the First World War. Perhaps the best-known Christmas story of the Western Front is the Christmas Truce of 1914, when peace briefly invaded some parts of the battlefields of the Western Front. Any let up was, however, only very temporary, as is shown through the letters sent home over Christmas 1914 by Sister Kate Luard.

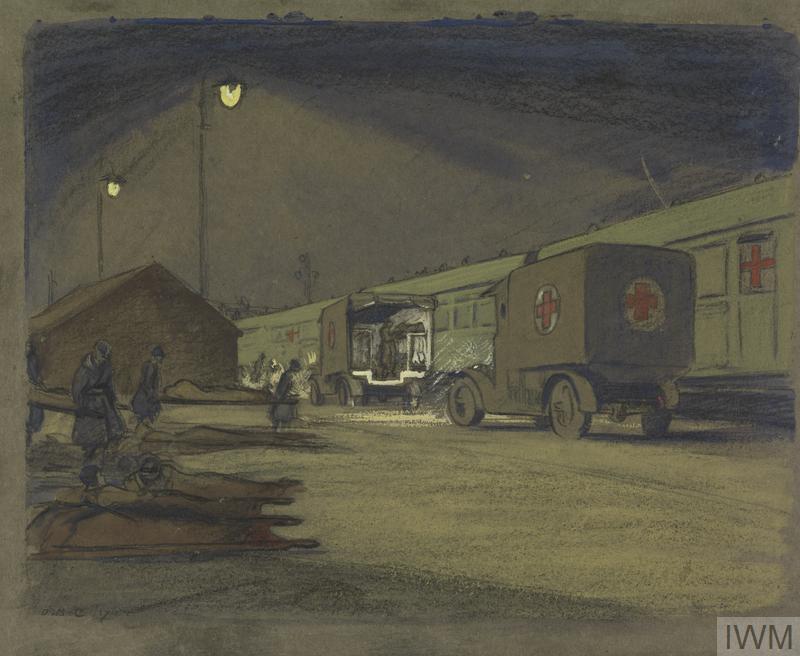

Kate served as a nurse throughout the First World War, and was at this time working on Ambulance Trains in Northern France. These special trains were kitted out with bunk beds to transport sick and wounded troops from the front to base hospitals, or to ports from which they would be evacuated back to England.

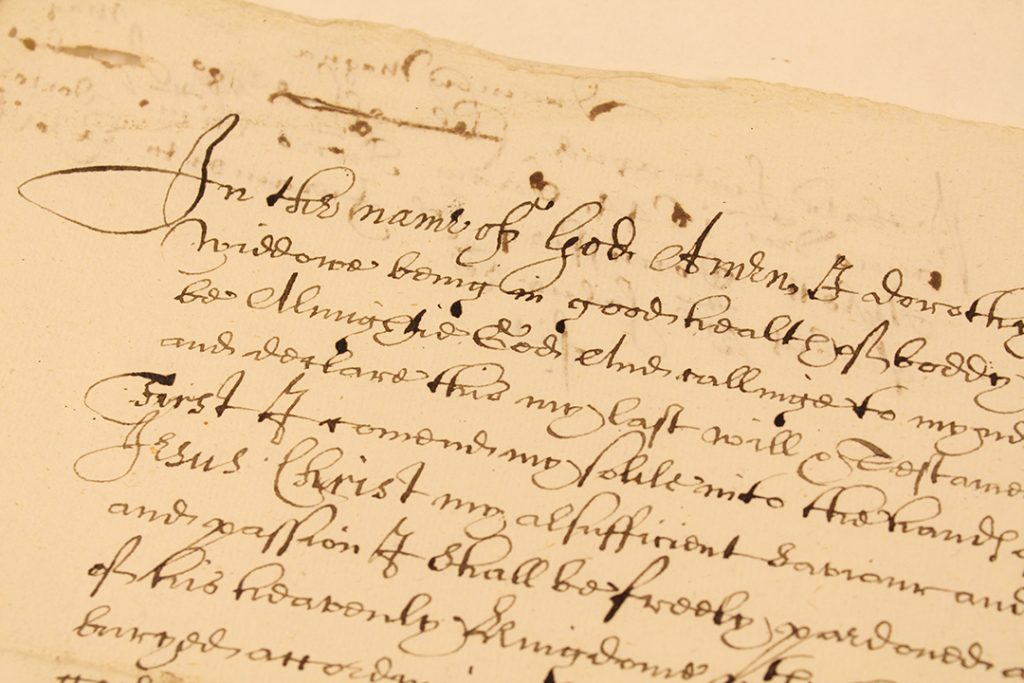

The letters below are all included in Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front, 1914-1915, which was published anonymously during the war. A copy is available in the ERO library.

Wednesday 23rd December, 1914

We loaded up at Lillers late on Monday night with one of the worst loads we’ve ever taken, all wounded, half Indians and half British.

You will see by Tuesday’s French communiqués that some of our trenches had been lost, and these had been retaken by the H.L.I. [Highlight Light Infantry], Manchesters, and 7th D.G.’s [Dragoon Guards].

It was a dark wet night, and the loading people were half-way up to their knees in black mud, and we didn’t finish loading till 2 a.m., and were hard at it trying to stop hæmorrhage, &c., till we got them off the train at 11 yesterday morning; the J.J.’s [lice] were swarming, but a large khaki pinny tying over my collar, and with elastic wristbands, saved me this time. One little Gurkha with his arm just amputated, and a wounded leg, could only be pacified by having acid drops put into his mouth and being allowed to hug the tin.

Interior of Ambulance Train at Boulogne. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205249852

Another was sent on as a sitting-up case. Half-way through the night I found him gasping with double pneumonia; it was no joke nursing him with seven others in the compartment. He only just lived to go off the train.

Another one I found dead about 5.30 a.m. We were to have been sent on to Rouen, but the O.C. Train reported too many serious cases, and so they were taken off at B. It was a particularly bad engine-driver too.

I got some bath water from a friendly engine, and went to bed at 12 next day.

We were off again the same evening, and got to B. this morning, train full, but not such bad cases, and are on our way back again now: expect to be sent on to Rouen. Now we are three instead of four Sisters, it makes the night work heavier, but we can manage all right in the day. In the last journey some of the worst cases got put into the top bunks, in the darkness and rush, and one only had candles to do the dressings by. One of the C.S.’s was on leave, but has come back now. All the trains just then had bad loads: the Clearing Hospitals were overflowing.

The Xmas Cards have come, and I’m going to risk keeping them till Friday, in case we have patients on the train. If not, I shall take them to a Sister I know at one of the B. hospitals.

We have got some H.A.C. [Honourable Artillery Company] on this time, who try to stand up when you come in, as if you were coming into their drawing-room. The Tommies in the same carriage are quite embarrassed. One boy said just now, “We ‘ad a ‘appy Xmas last year.”

“Where?” I said.

“At ‘ome, ‘long o’ Mother,” he said, beaming.

Christmas Eve, 1914

And no fire and no chauffage, and cotton frocks; funny life, isn’t it? And the men are crouching in a foot of water in the trenches and thinking of “‘ome, ‘long o’ Mother,”—British, Germans, French, and Russians. We are just up at Chocques going to load up with Indians again. Had more journeys this week than for a long time; you just get time to get what sleep the engine-driver and the cold will allow you on the way up.

8 p.m.—Just nearing Boulogne with another bad load, half Indian, half British; had it in daylight for the most part, thank goodness! Railhead to-day was one station further back than last time, as the —— Headquarters had to be evacuated after the Germans got through on Sunday. The two regiments, Coldstream Guards and Camerons, who drove them back, lost heavily and tell a tragic story. There are two men (only one is a boy) on the train who got wounded on Monday night (both compound fracture of the thigh) and were only taken out of the trench this morning, Thursday, to a Dressing Station and then straight on to our train. (We heard the guns this morning.) Why they are alive I don’t know, but I’m afraid they won’t live long: they are sunken and grey-faced and just strong enough to say, “Anyway, I’m out of the trench now.” They had drinks of water now and then in the field but no dressings, and lay in the slush. Stretcher-bearers are shot down immediately, with or without the wounded, by the German snipers.

Etaples Hospital Siding : a VAD convoy unloading an ambulance train at night (Art.IWM ART 3089) © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/19897

And this is Christmas, and the world is supposed to be civilised. They came in from the trenches to-day with blue faces and chattering teeth, and it was all one could do to get them warm and fed. By this evening they were most of them revived enough to enjoy Xmas cards; there were such a nice lot that they were able to choose them to send to Mother and My Young Lady and the Missis and the Children, and have one for themselves.

The Indians each had one, and salaamed and said, “God save you,” and “I will pray to God for you,” and “God win your enemies,” and “God kill many Germans,” and “The Indian men too cold, kill more Germans if not too cold.” One with a S.A. [South Africa] ribbon spotted mine and said, “Africa same like you.” [Kate also served as a military nurse in South Africa during the Boer War.]

Midnight.—Just unloaded, going to turn in; we are to go off again at 5 a.m. to-morrow, so there’ll be no going to church. Mail in, but not parcels; there’s a big block of parcels down at the base, and we may get them by Easter.

With superhuman self-control I have not opened my mail to-night so as to have it to-morrow morning.

Christmas Day, 1914

11 a.m.—On way up again to Béthune, where we have not been before (about ten miles beyond where we were yesterday), a place I’ve always hoped to see. Sharp white frost, fog becoming denser as we get nearer Belgium. A howling mob of reinforcements stormed the train for smokes. We threw out every cigarette, pipe, pair of socks, mits, hankies, pencils we had left; it was like feeding chickens, but of course we hadn’t nearly enough.

Every one on the train has had a card from the King and Queen in a special envelope with the Royal Arms in red on it. And this is the message (in writing hand)—

“With our best wishes for Christmas, 1914.

May God protect you and bring you home safe.

Mary R. George R.I.”

That is something to keep, isn’t it?

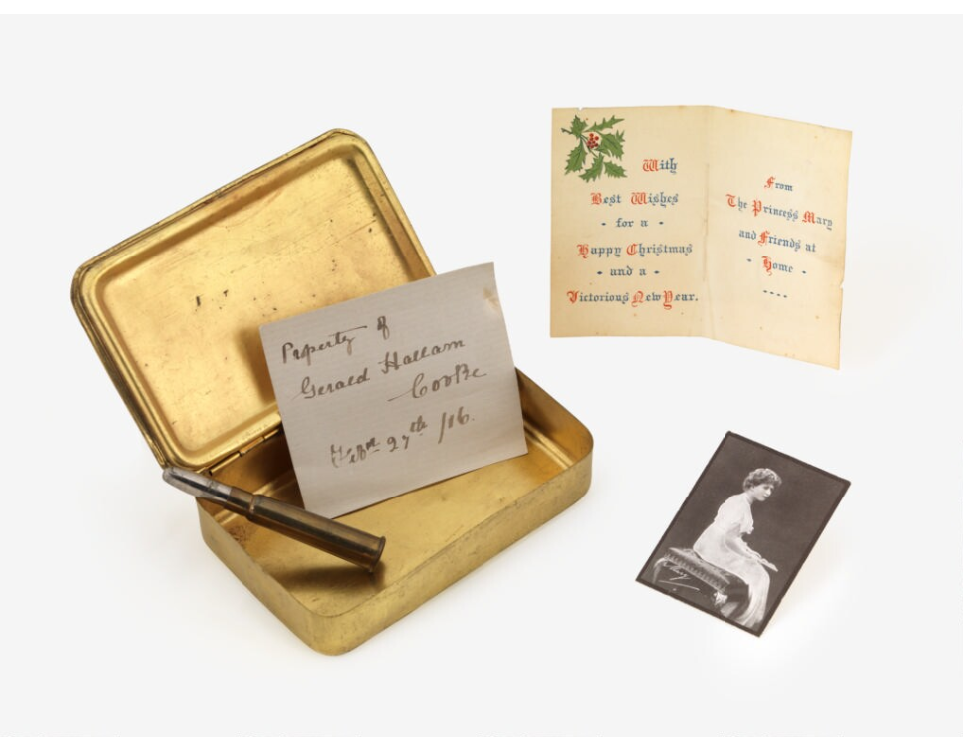

A Princess Mary Gift Fund Box. These tins containing small gifts were distributed to all troops as a Christmas present from the royal family. Image from the Imperial War Museum.

An officer has just told us that those men haven’t had a cigarette since they left S’hampton, hard luck. I wish we’d had enough for them. It is the smokes and the rum ration that has helped the British Army to stick it more than anything, after the conviction that they’ve each one got that the Germans have got to be “done in” in the end. A Sergt. of the C.G. [Coldstream Guards] told me a cheering thing yesterday. He said he had a draft of young soldiers of only four months’ service in this week’s business. “Talk of old soldiers,” he said, “you’d have thought these had had years of it. When they were ordered to advance there was no stopping them.”

After all we are not going to Béthune but to Merville again.

This is a very slow journey up, with long indefinite stops; we all got bad headaches by lunch time from the intense cold and a short night following a heavy day. At lunch we had hot bricks for our feet, and hot food inside, which improved matters, and I think by the time we get the patients on there will be chauffage.

The orderlies are to have their Xmas dinner to-morrow, but I believe ours is to be to-night, if the patients are settled up in time.

Do not think from these details that we are at all miserable; we say “For King and Country” at intervals, and have many jokes over it all, and there is the never-failing game of going over what we’ll all do and avoid doing After the War.

7 p.m.— Loaded up at Merville and now on the way back; not many badly wounded but a great many minor medicals, crocked up, nothing much to be done for them. We may have to fill up at Hazebrouck, which will interrupt the very festive Xmas dinner the French Staff are getting ready for us. It takes a man, French or British, to take decorating really seriously. The orderlies have done wonders with theirs. Aeroplanes done in cotton-wool on brown blankets is one feature.

This lot of patients had Xmas dinner in their Clearing Hospitals to-day, and the King’s Xmas card, and they will get Princess Mary’s present. Here they finished up D.’s Xmas cards and had oranges and bananas, and hot chicken broth directly they got in.

12 Midnight.—Still on the road. We had a very festive Xmas dinner, going to the wards which were in charge of nursing orderlies between the courses. Soup, turkey, peas, mince pie, plum pudding, chocolate, champagne, absinthe, and coffee. Absinthe is delicious, like squills. We had many toasts in French and English. The King, the President, Absent Friends, Soldiers and Sailors, and I had the Blessés [injured] and the Malades [sick]. We got up and clinked glasses with the French Staff at every toast, and finally the little chef came in and sang to us in a very sweet musical tenor. Our great anxiety is to get as many orderlies and N.C.O.’s as possible through the day without being run in for drunk, but it is an uphill job; I don’t know where they get it.

We are wondering what the chances are of getting to bed to-night.

4 a.m.—Very late getting in to B.; not unloading till morning. Just going to turn in now till breakfast time. End of Xmas Day.