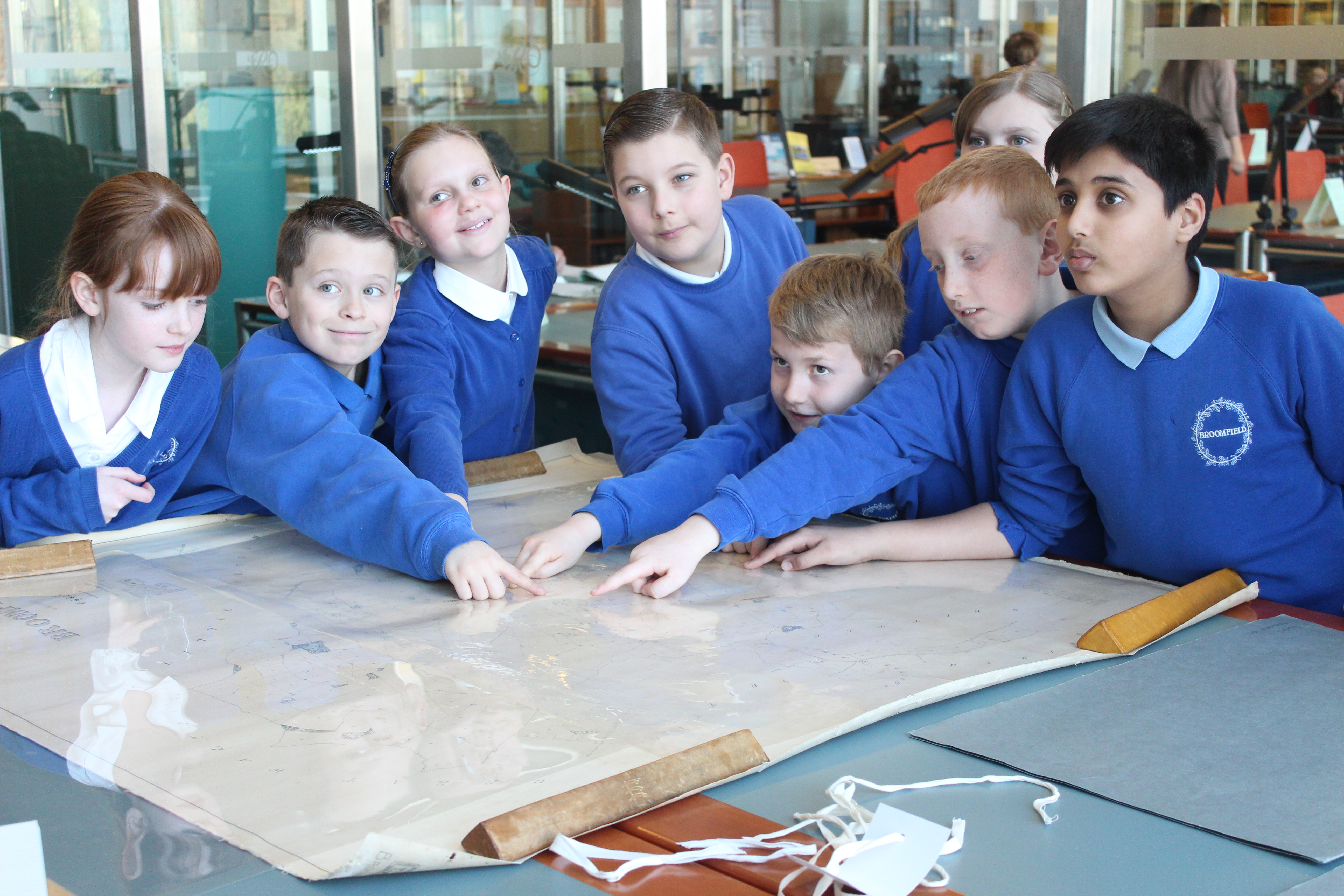

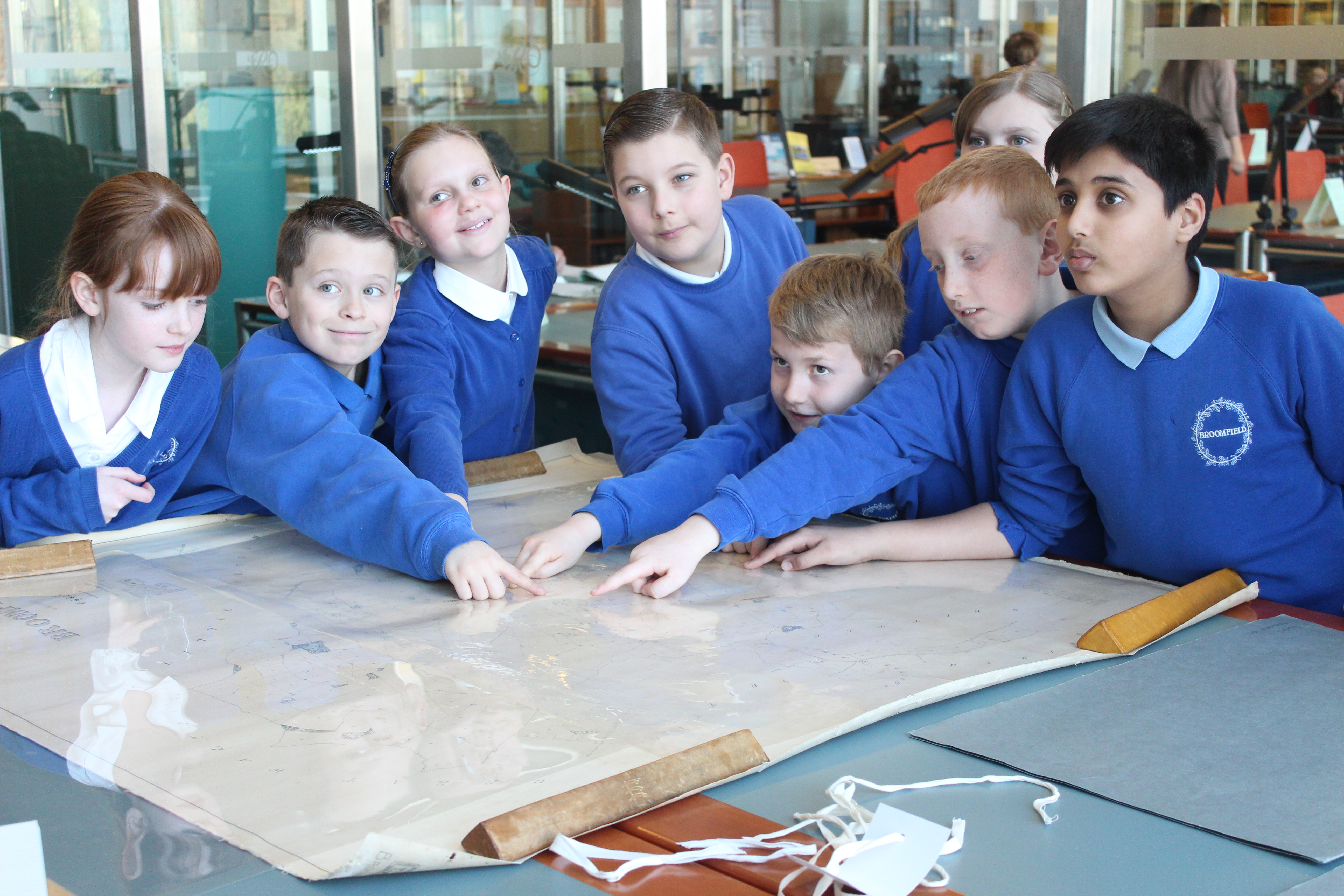

This guest post is written by Ben, Grace, Evie, Akmal, Toby, Ben, Grace, Lucas and Bella who are all in year 5 at Broomfield Primary School. They were shown around the ERO by Neil Wiffen, Public Service Team Manager, and Hannah Salisbury, Access and Participation Officer. If you would like to arrange a visit for an educational group, please get in touch with us on ero.events@essex.gov.uk

My teacher and a small group of pupils were invited to The Essex Record Office. Not the CD, track kind of record: the letter, diary, document kind of record. We were not just fascinated to find out some amazing facts, we were amazed to see some facts that gave us a link to things from hundreds of years ago. On our journey through time we filled our brains with lots of information and fun facts.

Why does the Essex Record Office (ERO) exist? Some people have interesting artefacts in their home but it’s no good having it all there! The ERO provide the capability of looking at all the information you need in one place. You do not have to make appointments in different buildings, the ERO has everything you need, but they have certain rules. These include not taking any bags (at all!) into the Searchroom. This is because some naughty people try and steal the information. The other rule was to use pencil only, as they don’t want to ruin any documents or information. The ERO is for people of all ages – there is no limit. You cannot only just have fun and find out information, you can understand and communicate with the past.

When the ERO was opened in 2000, there was a model made of a flower designed by pupils [ed.: the sculpture which runs alongside the public stairs up to the Searchroom]. The roots were to represent that History is in the past, the stem shows that were are the present. The flower and the seeds (which were binary 1 and 0s) represented the information travelling out in the future.

When we walked into the Searchroom Mr Wiffen explained about the organization of the documents. We thought it sounded quite complicated but actually it turned out to be a lot easier than we thought.  They have this website called Seax (a Seax is an Anglo Saxon stabbing sword and on the Essex County Council logo, the swords are Seaxes). The website called Seax helps you to find documents VERY quickly and efficiently. We searched for ‘Maps of Broomfield’ and it came up with 113 results. The earliest was made in 1591 and the latest was made in 2007. To search, you type in the key words, and then it shows you all the search results with the key words in date order.

They have this website called Seax (a Seax is an Anglo Saxon stabbing sword and on the Essex County Council logo, the swords are Seaxes). The website called Seax helps you to find documents VERY quickly and efficiently. We searched for ‘Maps of Broomfield’ and it came up with 113 results. The earliest was made in 1591 and the latest was made in 2007. To search, you type in the key words, and then it shows you all the search results with the key words in date order.

Hannah then informed us about a pie chart that someone made from the information in a book called a Parish Register which had a list of Births, Deaths or Marriages. Somebody looked at details telling us about deaths in the 1830s. We were shocked to hear that over half the people died under the age of 10!!

We definitely realised that Seax was helpful, especially for people who live overseas and love historical documents, because anyone around the world can ask for things to be put on there. It is much cheaper than travelling to the ERO, but it was more fun to go there for our visit.

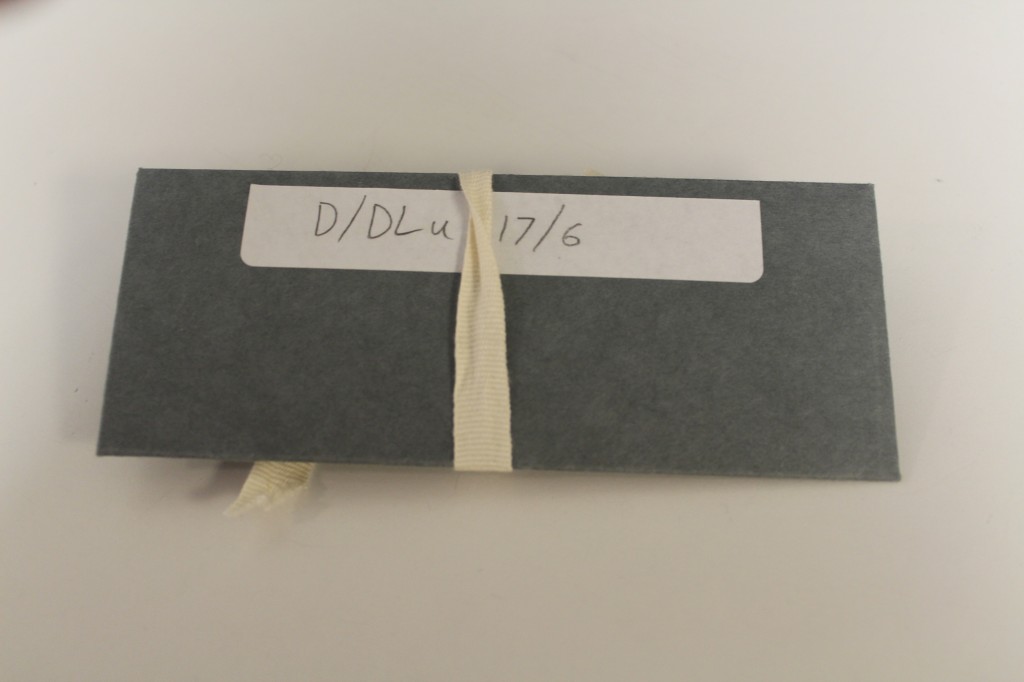

After we observed the picture-perfect painting of James I [ed.: on display in the Searchroom], Hannah told us that when monarchs wanted portraits of themselves, they would have chosen props that represented them. For example, Elizabeth I chose a globe to show she has invaded different nations. We should look for clues in paintings, not just at the person who has been painted.  Next Mr Wiffen pulled a draw out full of envelopes and picked up a microfiche, which is miniscule pictures of wills and newspapers. The reason why the newspapers are made smaller is because you can keep lots of information on a small sheet of film and the big news paper takes up a lot of room, is very thin and will disintegrate. You have to place the microfiche in a machine, so that when you look through, it will magnify and illuminate it big enough for people to read it.

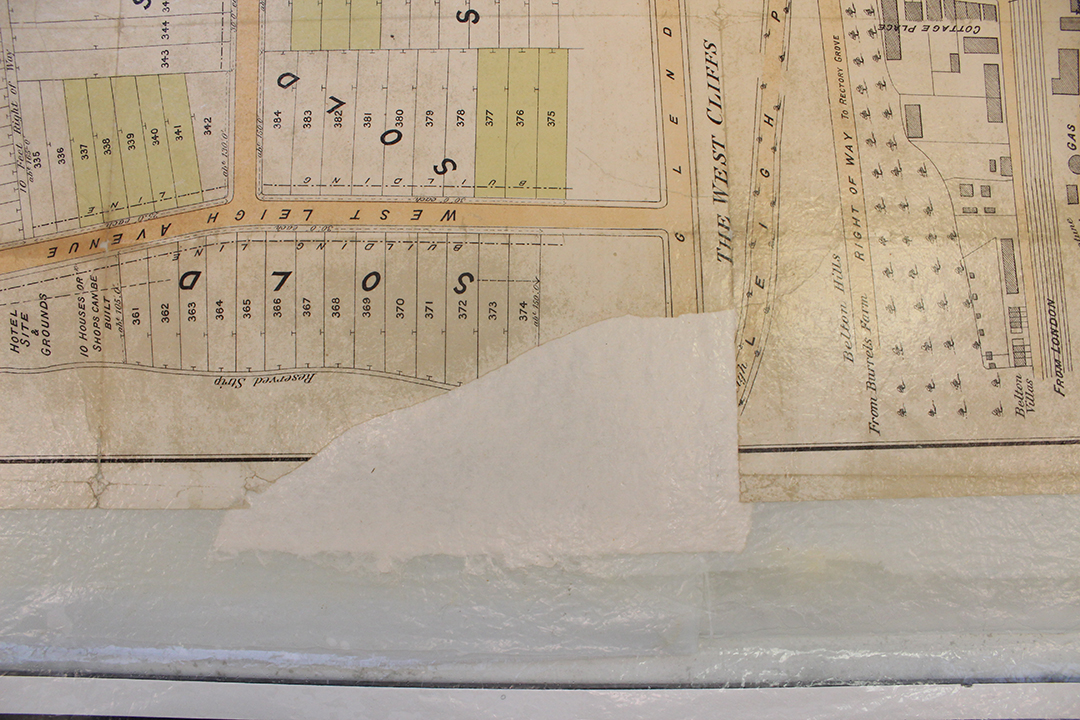

Next Mr Wiffen pulled a draw out full of envelopes and picked up a microfiche, which is miniscule pictures of wills and newspapers. The reason why the newspapers are made smaller is because you can keep lots of information on a small sheet of film and the big news paper takes up a lot of room, is very thin and will disintegrate. You have to place the microfiche in a machine, so that when you look through, it will magnify and illuminate it big enough for people to read it.  Mr Wiffen showed us a couple of unique maps of Broomfield in the past. The first one we looked at was from 1846. It was an enormous map and Broomfield looked empty and lonely, with fewer houses and more greenery. We found that our school and houses had not been built yet. We put our fingers on our invisible houses. Bromfield Hospital was not there yet either, but the area where it would be built was called Puddings Wood.

Mr Wiffen showed us a couple of unique maps of Broomfield in the past. The first one we looked at was from 1846. It was an enormous map and Broomfield looked empty and lonely, with fewer houses and more greenery. We found that our school and houses had not been built yet. We put our fingers on our invisible houses. Bromfield Hospital was not there yet either, but the area where it would be built was called Puddings Wood.  Then we looked at the earliest map of Broomfield which was made in 1591 by John Walker.We could see the beautiful colours to show the roads, houses and landmarks. It was made for Widow Wealde and showed all of her land.

Then we looked at the earliest map of Broomfield which was made in 1591 by John Walker.We could see the beautiful colours to show the roads, houses and landmarks. It was made for Widow Wealde and showed all of her land.  The next map we looked at was created and drawn by hand in 1771 of Broomfield, it is 244 years old. It showed a field called Drakes Fut, which is near our school. It is now called Dragon Foot Field. We talked about a legend from 1,00 years ago. Every day workers would build a bit of Broomfield Church and use strange red bricks and tiles that they found in the field. But in the night, when they were sleeping, a dragon would take all the bricks and bury them back in the field. Imagine how the builders felt when the dragon took their building materials! They must have felt frustrated and scared. Nowadays, we know the bricks and tiles were made by Romans and there was a villa in that field. Bricks and tiles from the villa can be seen in the walls of Broomfield Church.

The next map we looked at was created and drawn by hand in 1771 of Broomfield, it is 244 years old. It showed a field called Drakes Fut, which is near our school. It is now called Dragon Foot Field. We talked about a legend from 1,00 years ago. Every day workers would build a bit of Broomfield Church and use strange red bricks and tiles that they found in the field. But in the night, when they were sleeping, a dragon would take all the bricks and bury them back in the field. Imagine how the builders felt when the dragon took their building materials! They must have felt frustrated and scared. Nowadays, we know the bricks and tiles were made by Romans and there was a villa in that field. Bricks and tiles from the villa can be seen in the walls of Broomfield Church.

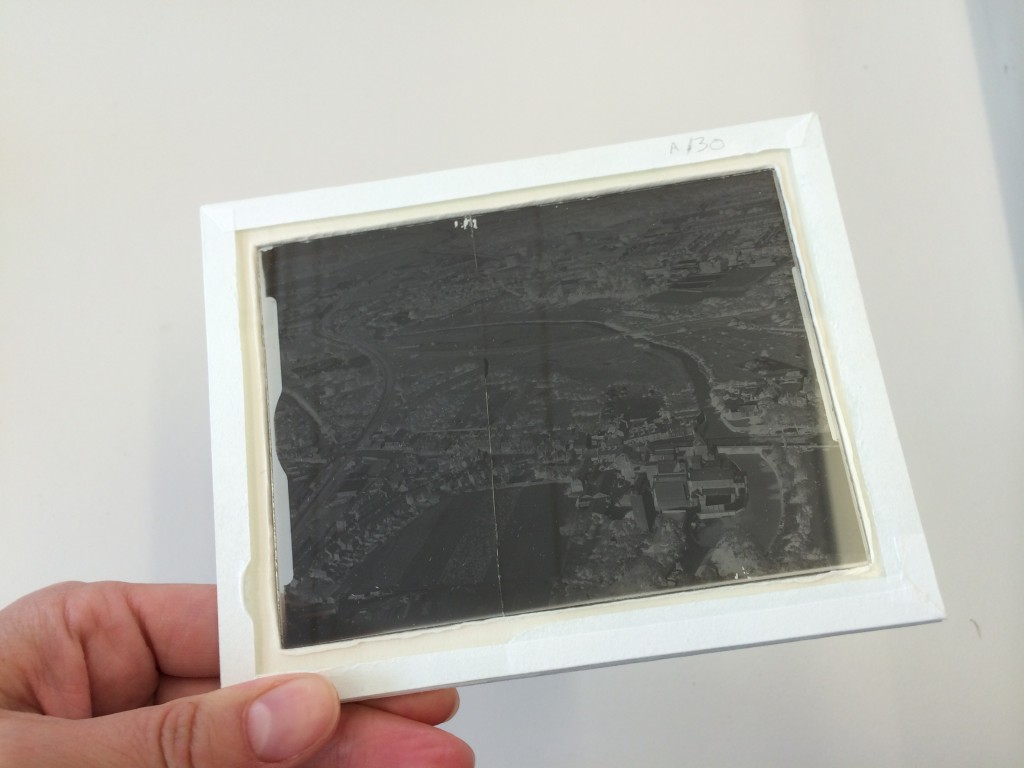

Shortly after, we were showed a map from 1919 in Broomfield. There were 2 coffee shops and here is a photograph to prove that it really did exist. We were surprised that people used to go out for a coffee, just like we do today. Coffee shops were there to stop people from spending all of their money in the pubs. But even 100 years ago there were no roads, just mud. The road outside Broomfield Primary School was just mud too – and it looked VERY muddy.

One of Broomfield’s two coffee shops (from the Fred Spalding Collection)

Broomfield School and a very muddy unmade road (from the Fred Spalding Collection)

There is a pub called The Saracens Head on the High Street in Chelmsford. We saw a photograph if it showing the American soldiers who used to go there to interact and relax. Back in the Second World War, Mr Wiffen’s dad (who lived in Broomfield) had heard planes fighting overhead when he was a boy. Would you like it if bullet cases were falling on your shed? That’s what he could hear, but he was probably in his Anderson Shelter. Forty years later, he found a spent bullet case (probably from those fights) in his back garden.

Broomfield has lots of things in the ground from different periods of history. How would you feel to be standing on history, or to never find artefacts that could be worth millions! We had an amazing time looking at the spectacular maps.

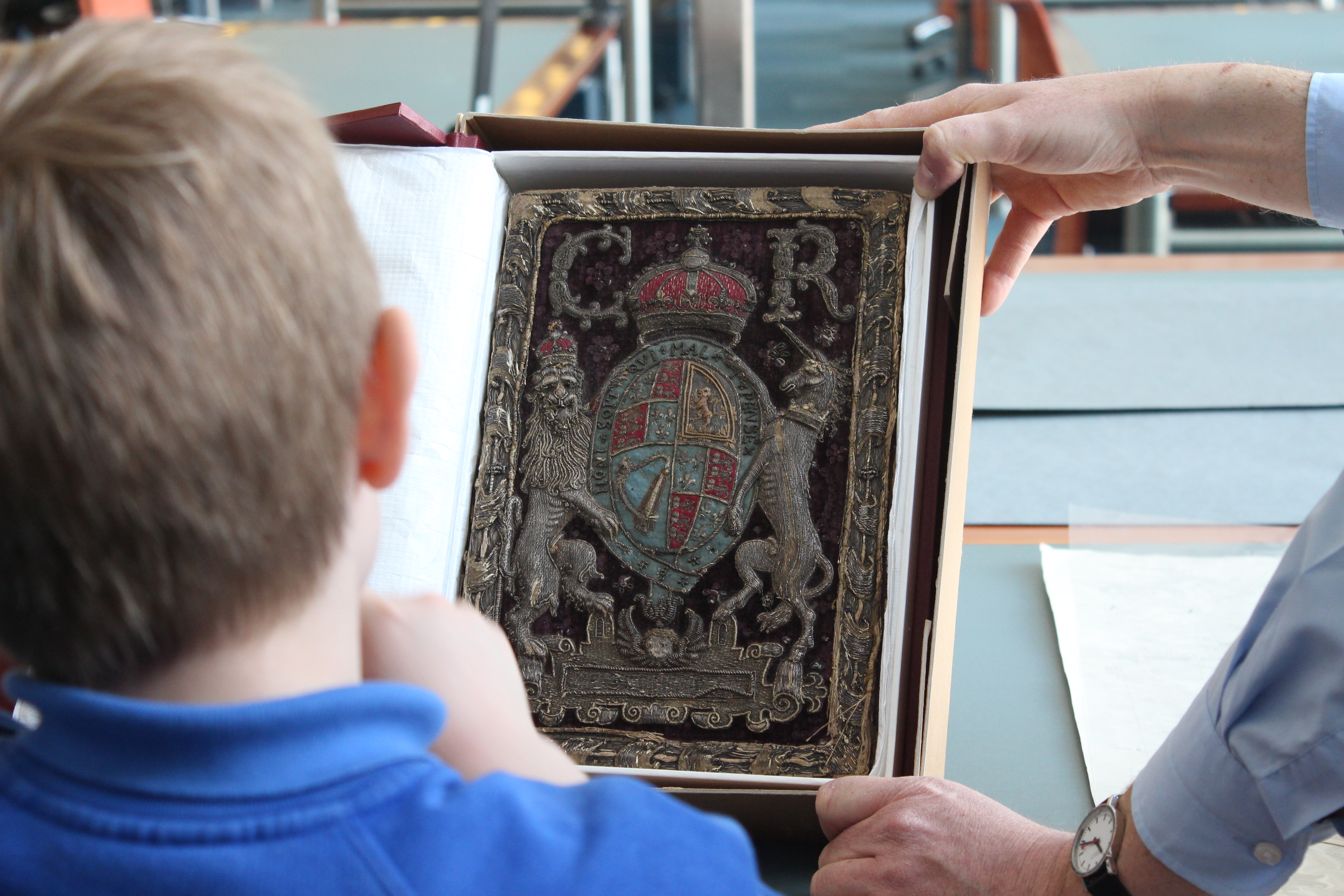

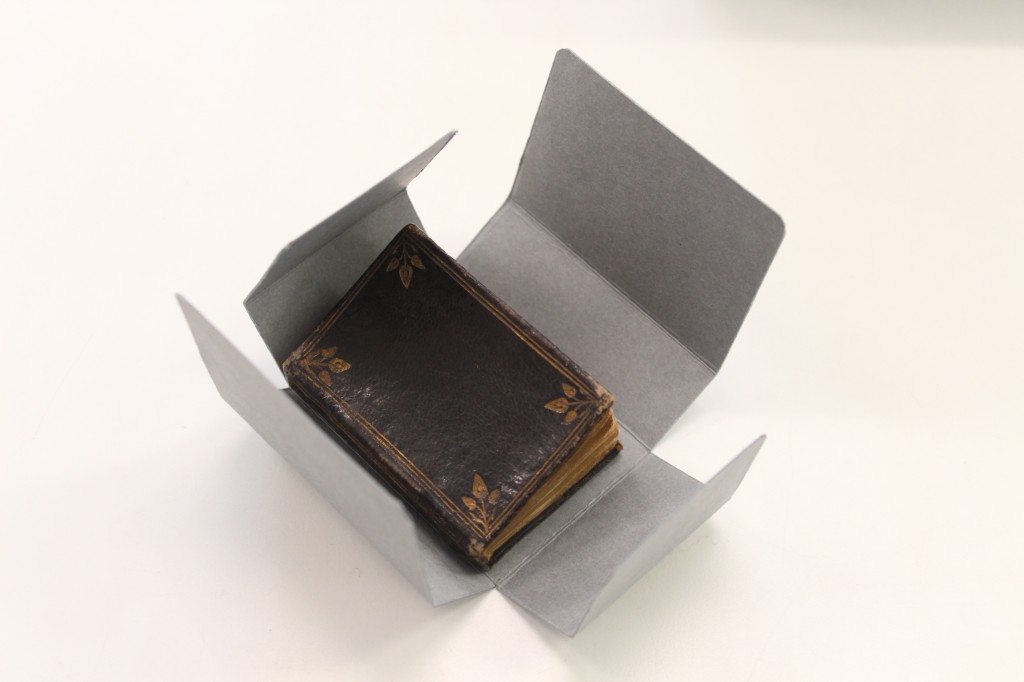

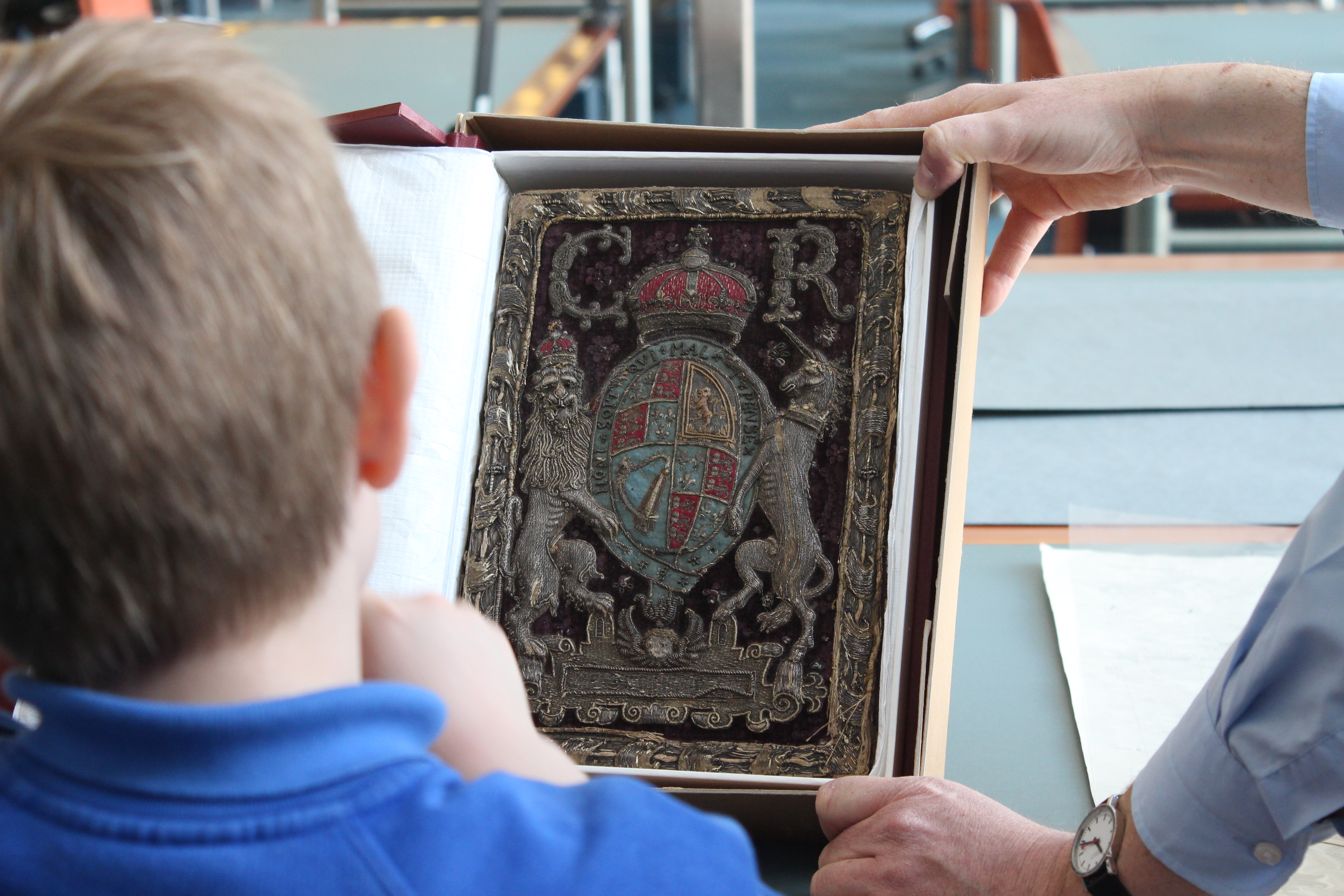

After that we carefully opened a box that was in another box with another padded cover. Inside was a special bible that Charles I had before his gruesome and terrifying beheading happened. Somehow, Charles’s librarian Patrick Young, got his hands on it and gave it to his granddaughter Sarah who gave it to the Broomfield Church.

When the Church was being renovated, apparently the builders dropped it by accident! They decided to give the responsibility to the ERO to protect the Bible forever. The Bible has an amazing silver outline with a glorious red velvet cover, decorated with a lion, a unicorn, a crest of arms and initials. IT MUST’VE COST MILLIONS!!!!! The lion was very detailed with tiny silver stitches – the mane swerving in different directions and the ribs and claws very clearly seen. He has two beady bead eyes.

When the Church was being renovated, apparently the builders dropped it by accident! They decided to give the responsibility to the ERO to protect the Bible forever. The Bible has an amazing silver outline with a glorious red velvet cover, decorated with a lion, a unicorn, a crest of arms and initials. IT MUST’VE COST MILLIONS!!!!! The lion was very detailed with tiny silver stitches – the mane swerving in different directions and the ribs and claws very clearly seen. He has two beady bead eyes.

The ERO looks after Log Books from different schools, and here is a page from Broomfield Primary School in 1912. The book sat on a special pillow to protect the spine and showed the beginning of the school summer holidays. the school was closed so that the children could go and help with pea picking for the harvest. Food was important – everyone needed to help collect enough food to get through the next winter. That is why we have six weeks off in the summer. Luckily we don’t actually have to pick peas any more!

Eventually, we reached the storage room after a long walk from the library. The storage room keeps all of the documents and old books safe. The humidity and temperature was cool enough to preserve them for even longer than usual. To access the room, Mr. Wiffen had to scan his staff card in a laser. We had to be quick going in because the door shut after 30 seconds!

As soon as we got in we felt a lot cooler and looked at huge rolls and lots of shelves and books. First of all, he showed us the stacks. These have codes on them to help staff find the right document quickly. They are moveable so they can fit more of them in. There are 8 miles of shelves altogether. He also told us that the red pipes let out a special gas during a fire to prevent the special files from burning. Water would damage the documents, and so would foam, so gas is safer for the documents. However, if the fire alarm goes off you have only 45 seconds to escape!

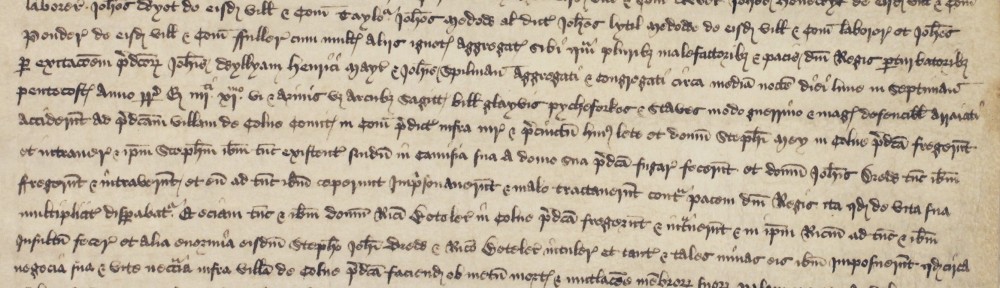

Next, Mr. Wiffen showed some precious packages, one of which was an Anglo Saxon document from 962 AD, written on parchment (Animal skin). They were deeds from Devon, part of Lord Petre’s collection. This is the oldest item in the collection.

Looking at the ERO’s oldest document, an Anglo-Saxon charter from 962 (D/DP T209)

He then showed us a huge, hand drawn and hand coloured old map of Chelmsford from 1591, by John Walker. Even though it was old, the colours were bright and beautiful. On the edge of Chelmsford, were two little lines to show the town gallows. Who would have thought they would build grizzly gallows in such a beautiful town? And right behind the town centre was a field called the Back Sides, where John Lewis will be built!

John Walker’s map of Chelmsford, 1591 (D/DM P1)

Lastly, we scurried out past the timed doors and saw a strange thing. It did look peculiar, but it was one of the camera’s dust covers: a chicken tea cosy! If you live in Australia and want a photograph of a document, they will use the really good camera to take an image and then send it to you.

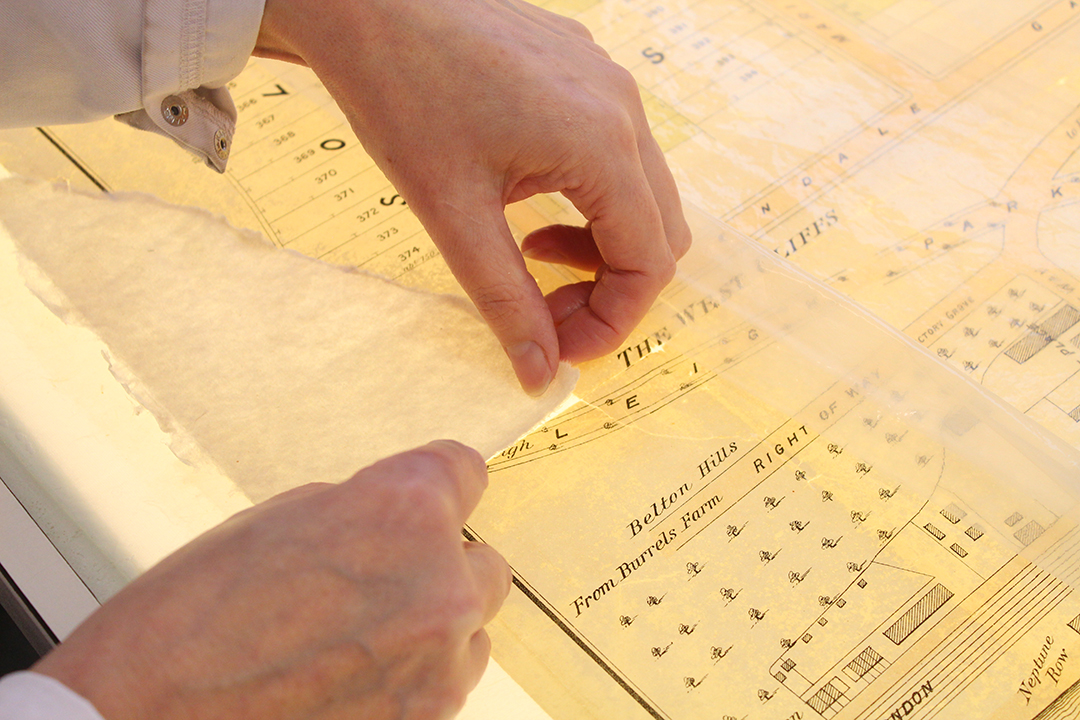

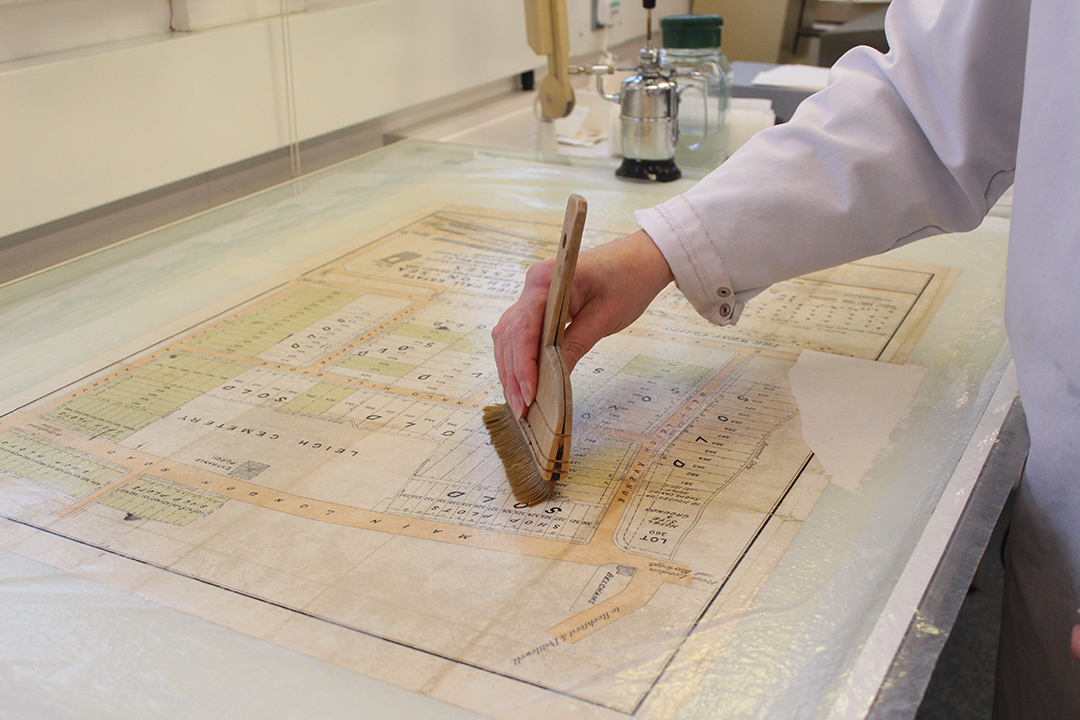

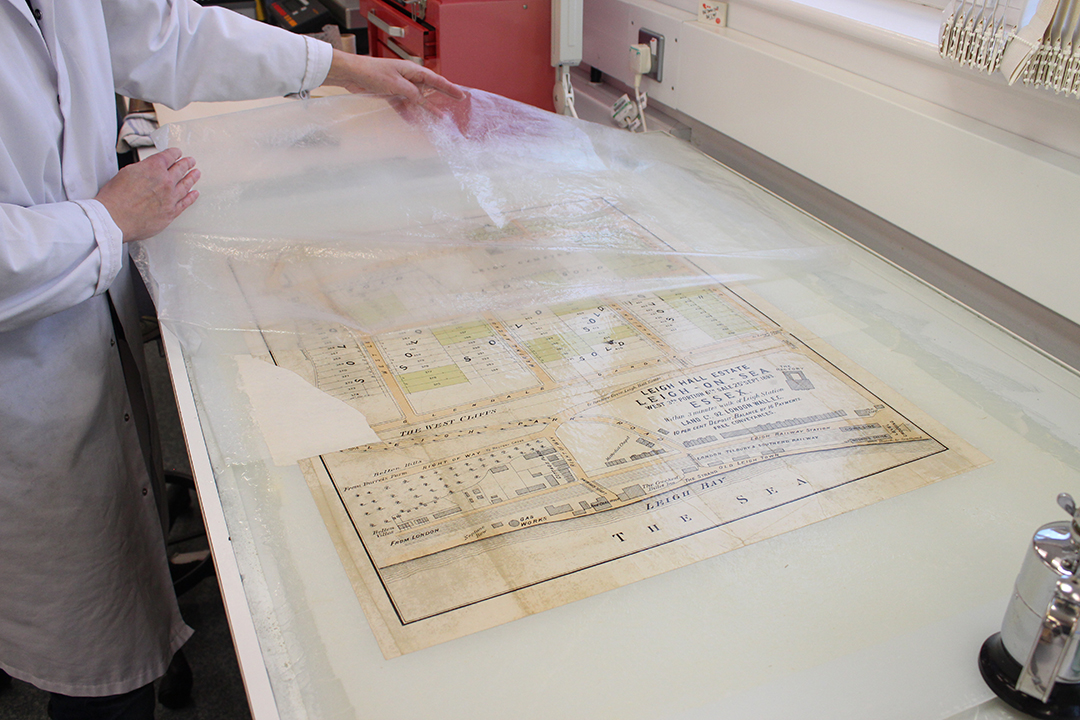

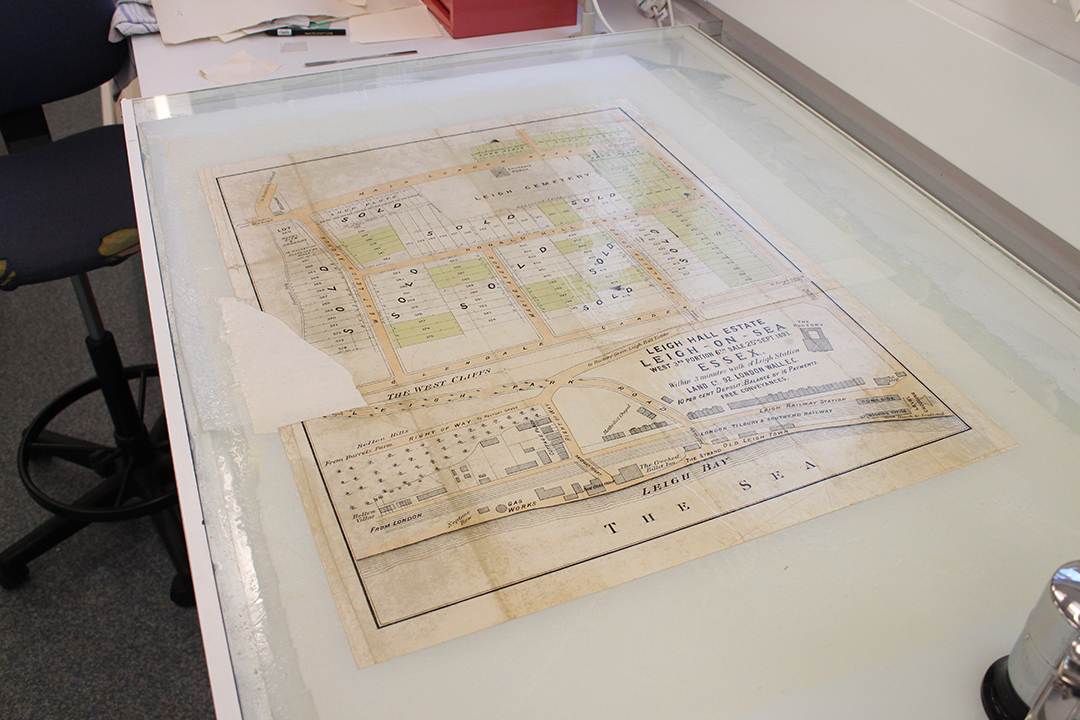

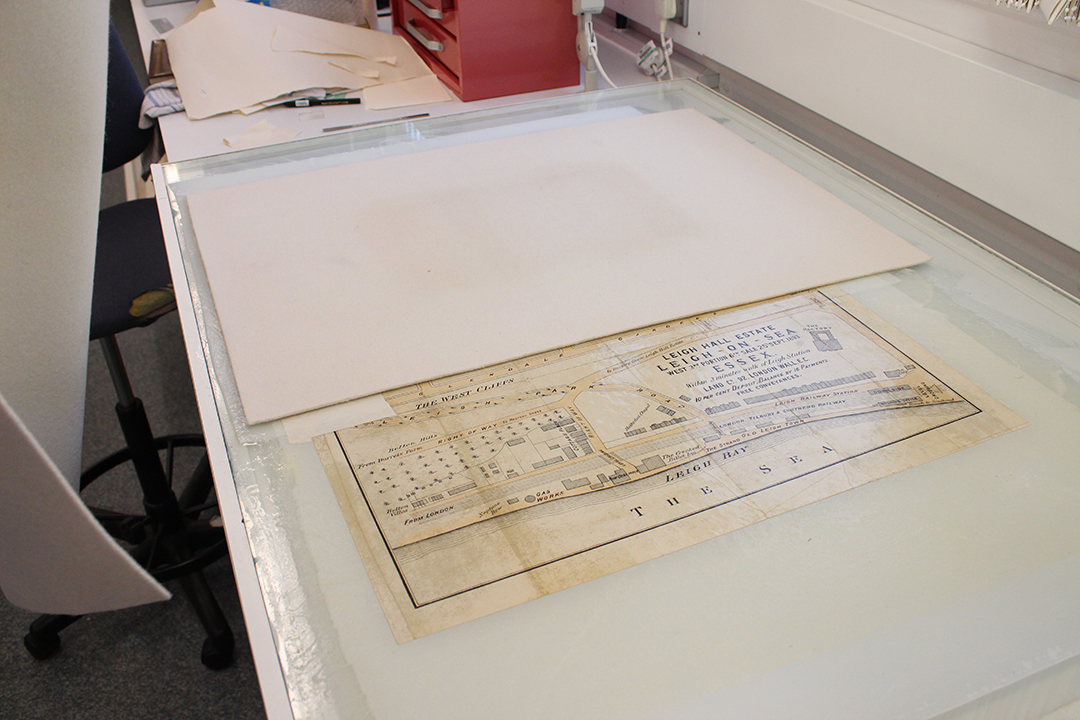

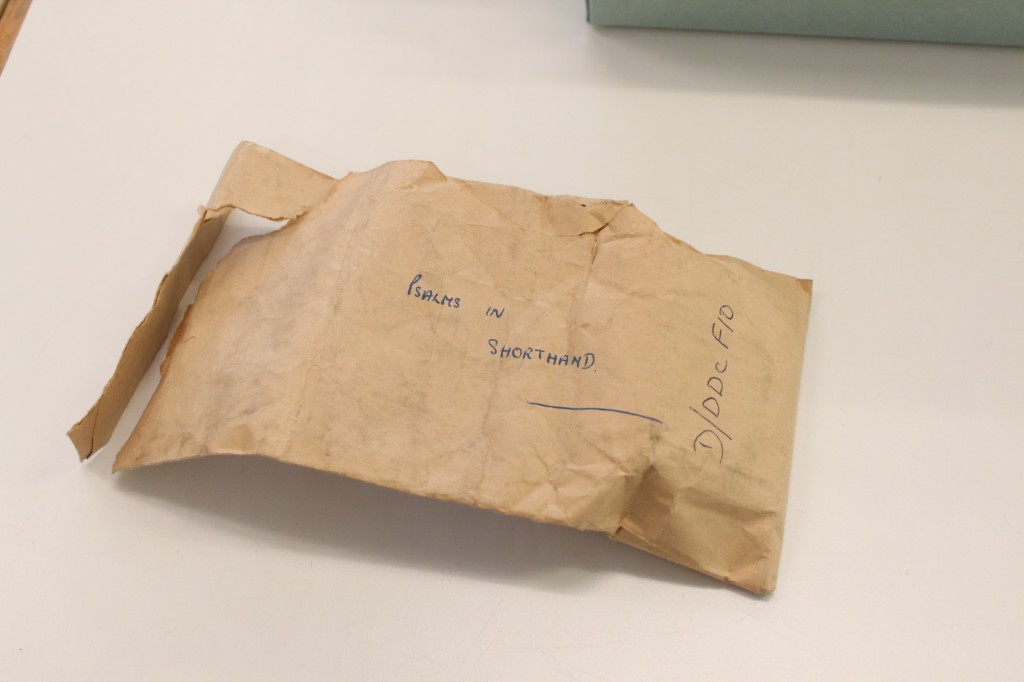

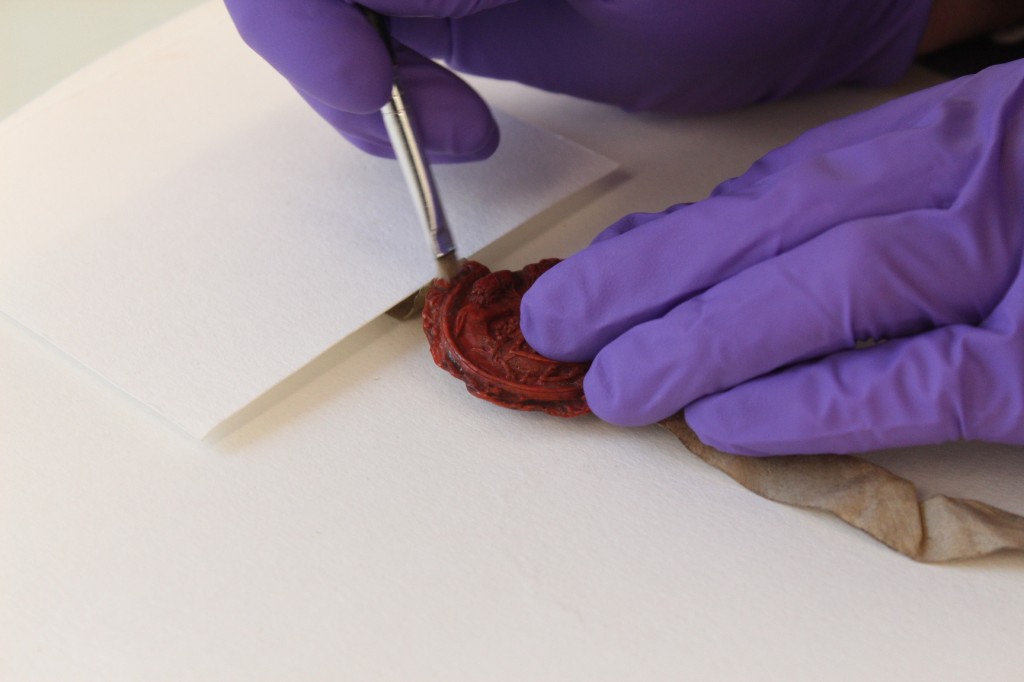

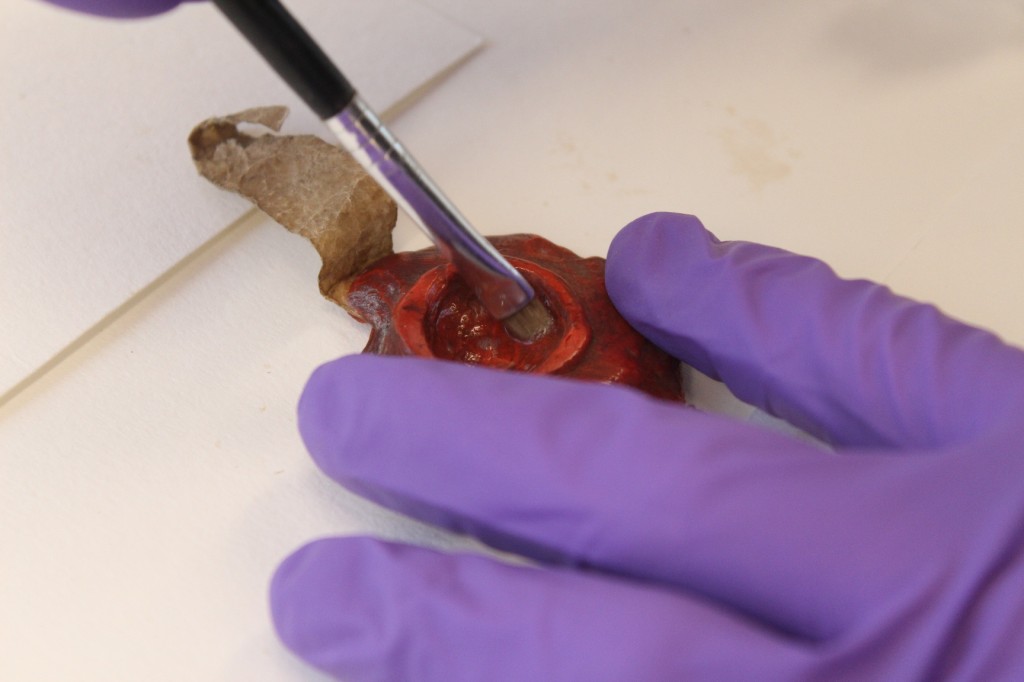

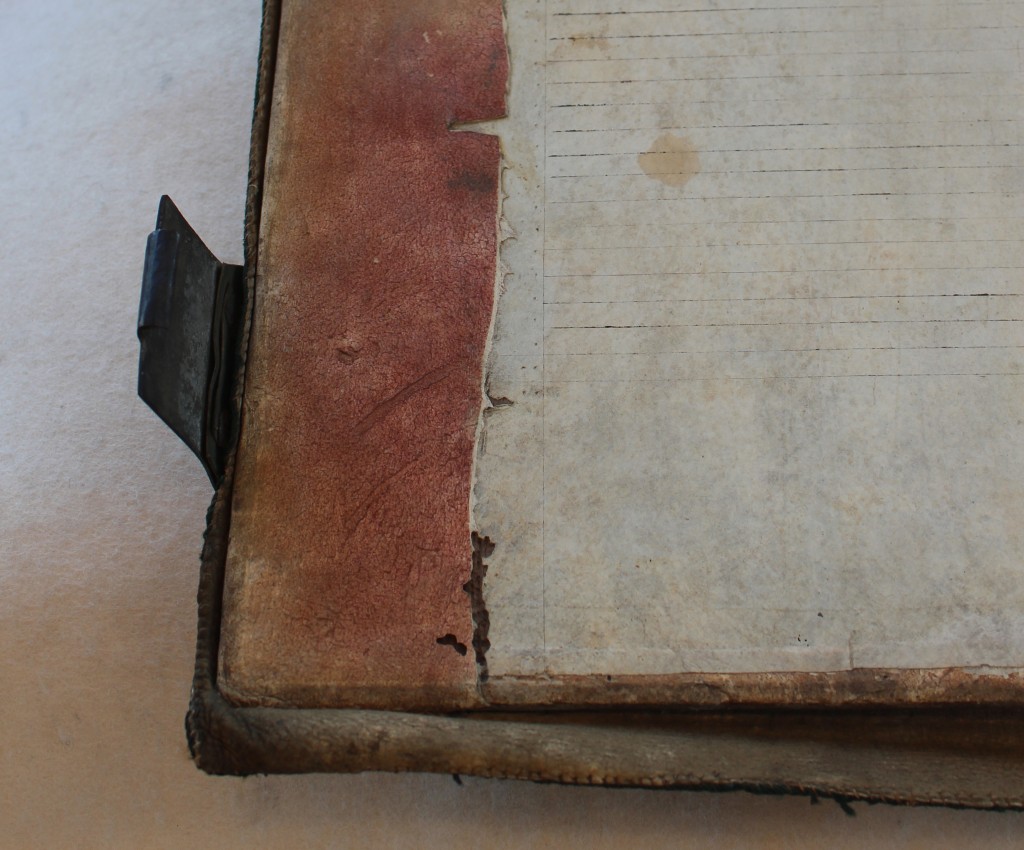

Then we continued our journey to the Conservation Room. The Conservation Room is a room where they carefully fix and clean documents, maps and letters. A lady called Diane showed us all the things that she needed, and some things that she couldn’t fix. For instance a letter, which was folded up into a bundle and tied up, had been burnt by fire and had got very brown. It felt harder than metal – however it would be very, very easy to break if anyone tried to unroll the document. Nobody would ever know what was written on it. On the other hand, some Americans have now invented a machine, which mysteriously x-rays the bundle and scans the letters by looking at the ink inside, and makes a reconstruction that shows you what it had on it before it went in the fire. Maybe one day somebody will be able to put this document in and see what it is all about. Right now, all we know is a date of 1917, which we found when we examined it.  Next Diane showed us a paper document that had lots of mould on it. She said it would never come off, so if you at home have very special letter or something else, make sure it’s not in your loft where mould will develop. The only writing on this was ‘{Be is re……..day of……year of the reign of our……. of Great Britain, Franc…….and fo forth.’ The rest of the paper had disintegrated. As well as that, we were allowed to hold a real piece of parchment. It is animal skin and is very strong. It lasts much better than paper so we could touch it. There also was large a circular thing made of wax. It looked a giant coin because it had Queen Victoria on her throne. On the other side, it was a picture of her on a horse. A quarter of it had been smashed on the floor. Most of words were in Latin, however most of it we could read. These big seals were attached to important documents to show that the King or Queen agreed with what was written inside it.

Next Diane showed us a paper document that had lots of mould on it. She said it would never come off, so if you at home have very special letter or something else, make sure it’s not in your loft where mould will develop. The only writing on this was ‘{Be is re……..day of……year of the reign of our……. of Great Britain, Franc…….and fo forth.’ The rest of the paper had disintegrated. As well as that, we were allowed to hold a real piece of parchment. It is animal skin and is very strong. It lasts much better than paper so we could touch it. There also was large a circular thing made of wax. It looked a giant coin because it had Queen Victoria on her throne. On the other side, it was a picture of her on a horse. A quarter of it had been smashed on the floor. Most of words were in Latin, however most of it we could read. These big seals were attached to important documents to show that the King or Queen agreed with what was written inside it.

Last of all, Diane showed us scientific equipment such as a measuring container that could make sure that when she fixed using different liquids, she had the right amount of it. For example if she needed a litre of water, she could make sure there’s not too much and not too little. There were other scientific instruments to make sure the temperature and humidity were exactly right in the room all the time. It was interesting to see how Science and History were used together in one job.

Last of all, Diane showed us scientific equipment such as a measuring container that could make sure that when she fixed using different liquids, she had the right amount of it. For example if she needed a litre of water, she could make sure there’s not too much and not too little. There were other scientific instruments to make sure the temperature and humidity were exactly right in the room all the time. It was interesting to see how Science and History were used together in one job.

We had a mind-blowing time at the ERO, our brains were stretched. It was an experience of a life time and an adventure beyond words. We had no idea it would be so interesting and would like to say thank you to the ERO for giving us an amazing tour, we learnt lots! It’s a brilliant place to find out many things. The people who work there are very kind and friendly. They were experts and shared all their knowledge and information with us from generations ago. We were mad at Mrs McIntyre (our teacher) for making us leave, and were desperate to stay to find out more about our own pasts and where we lived. We hope to be back soon…

By Ben, Grace, Evie, Akmal, Toby, Ben, Grace, Lucas and Bella, Broomfield Primary School