By archivist Lawrence Barker

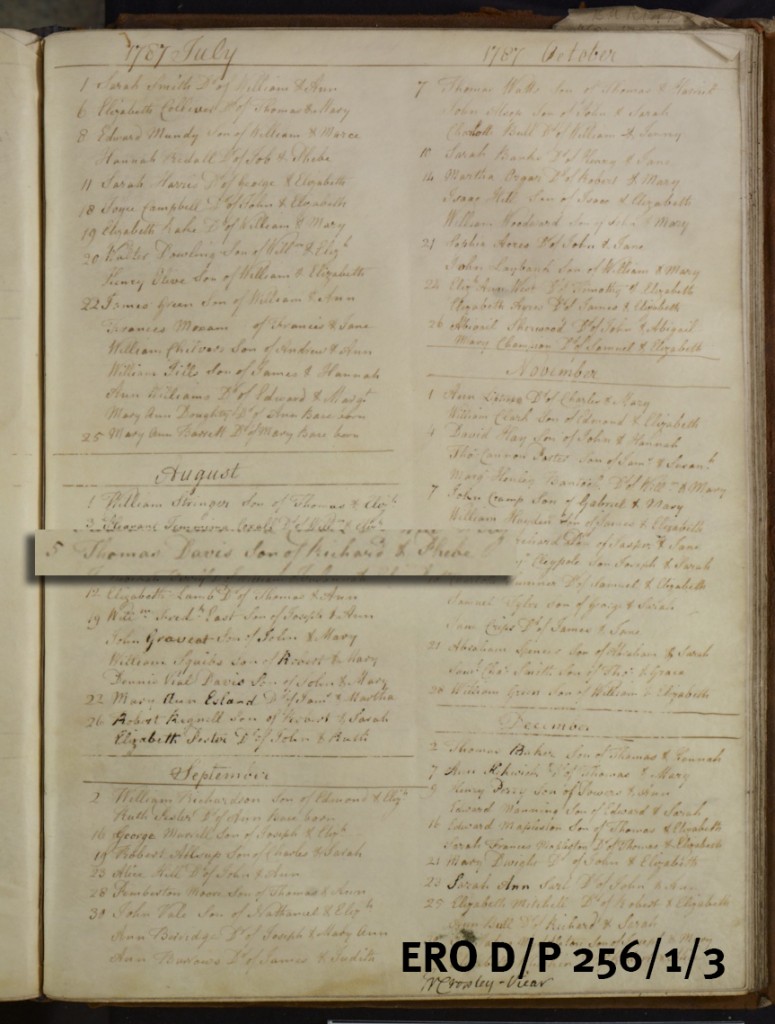

Whenever we give talks to people about parish records and their use in family history research, we make the point that some burial registers can give extra information about the deceased in addition to the bare details of name, date and age, and sometimes record background historical information.

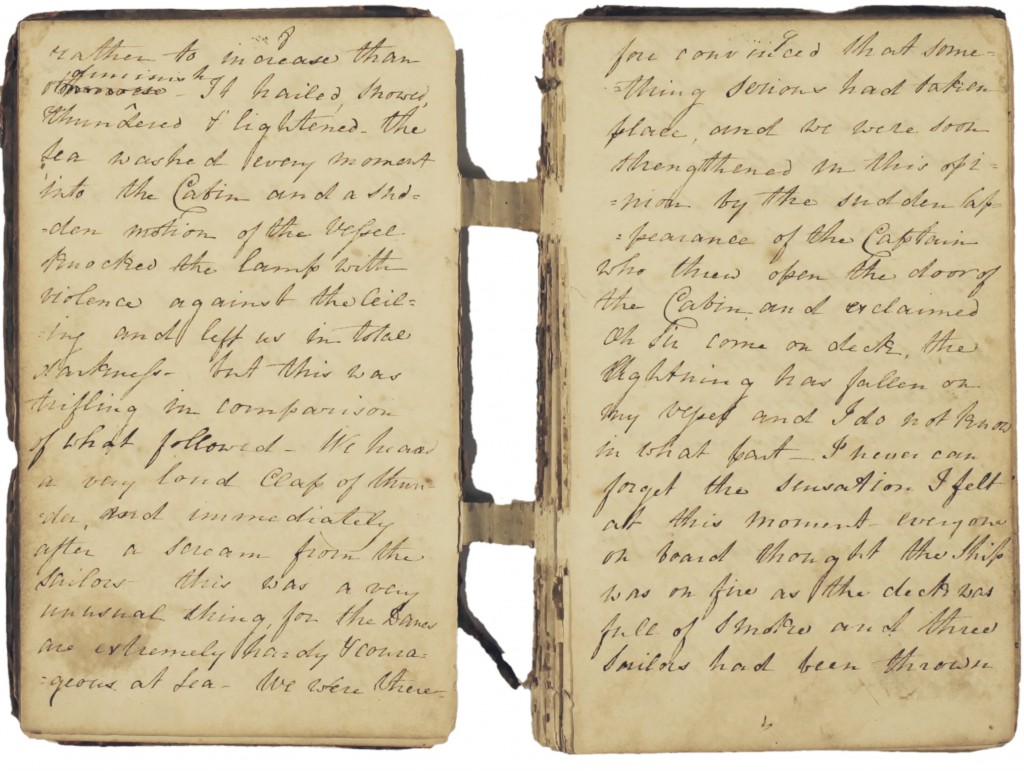

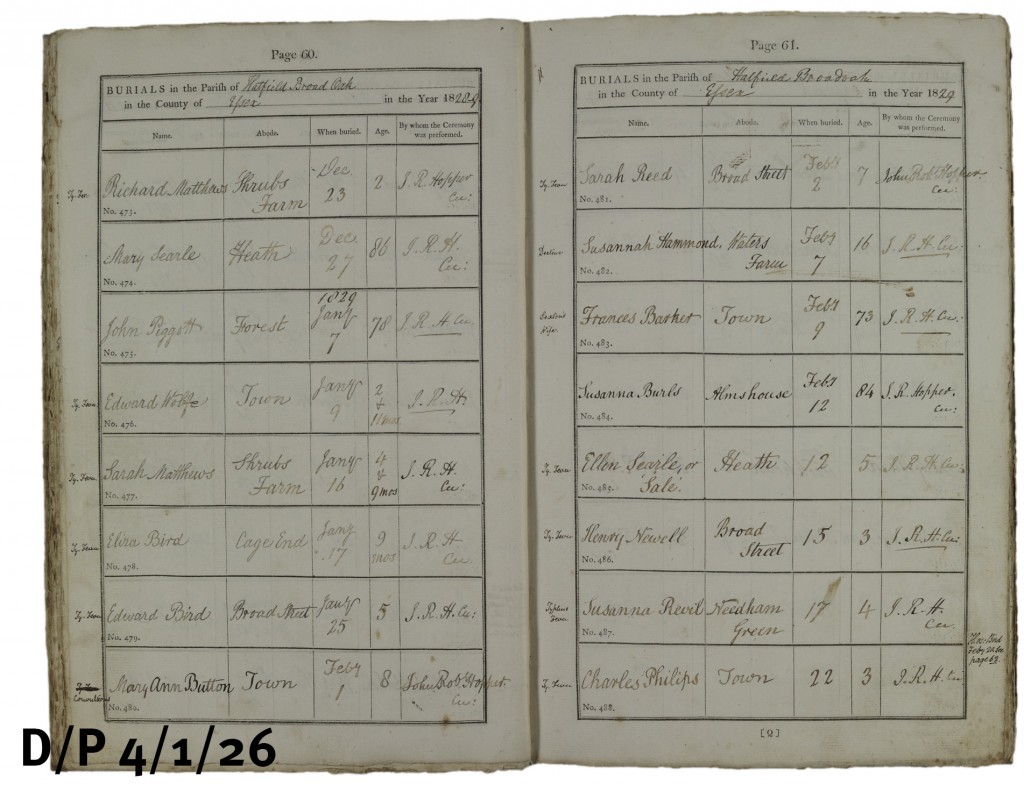

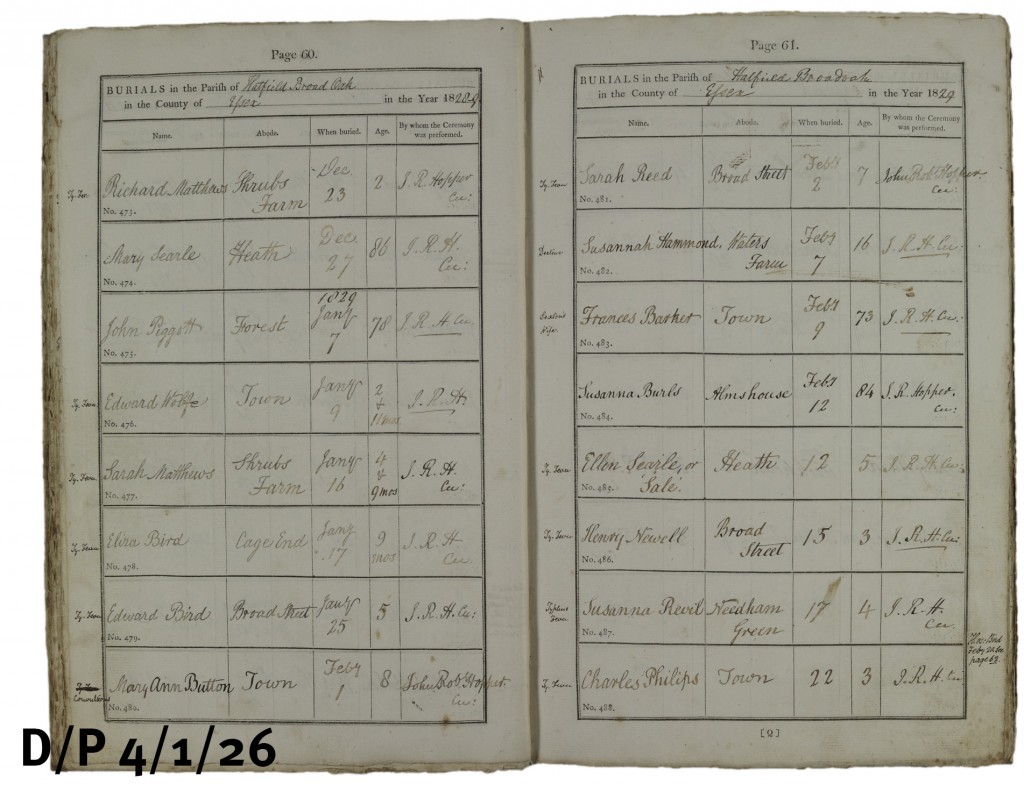

A case in point is the burial register for Hatfield Broad Oak, 1813-1859 (D/P 4/1/26), which was deposited with us in November 2011. Most of the register confines itself to recording the bare minimum details of name, abode, when buried, age and by whom the ceremony was performed, as stipulated under the terms of ‘Rose’s Act’ of 1812, which stated that “amending the Manner and Form of keeping and of preserving Registers of Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials of His Majesty’s Subjects in the several Parishes and Places in England, will greatly facilitate the Proof of Pedigrees of Persons claiming to be entitled to Real or Personal Estates, and otherwise of great public Benefit and Advantage”.

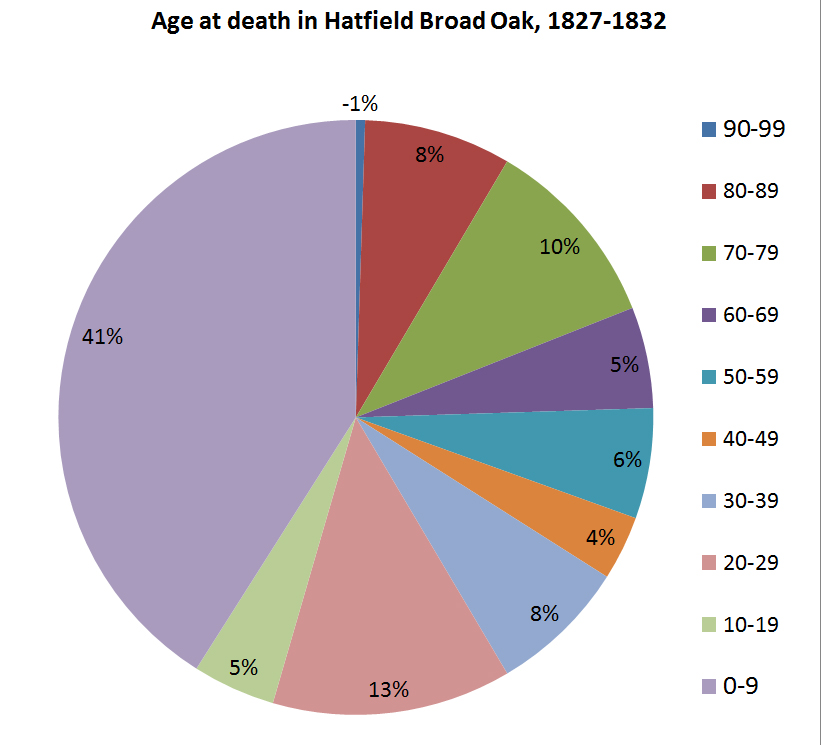

Nevertheless, even though the information is basic, we can still build up a picture of the demography of death in Hatfield Broad Oak which tells us something about what life might have been like then.

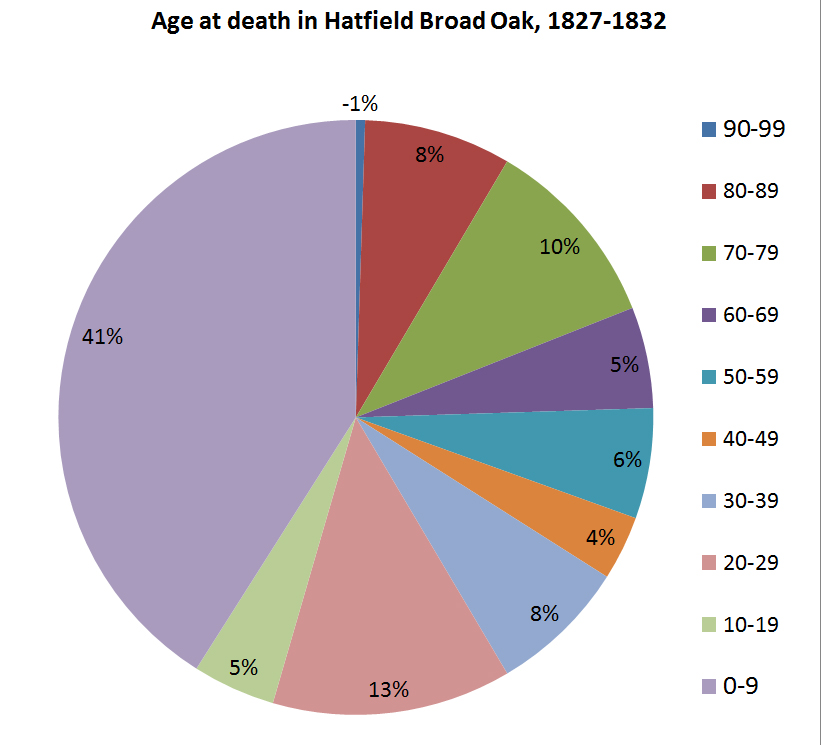

Pie chart showing age at death in Hatfield Broad Oak, 1827-1832, taken from the parish register. A total of 200 deaths are recorded during this period, and over 80 of them were children under 10 years old.

For example, looking at the ages of those buried (above), one forgets just how high the infant mortality rate used to be before improvements were brought about by modern hygiene and medical practice, and how likely it was having survived birth you might not have survived much beyond early childhood. The register shows that, out of the 200 or so burials which took place between 1827 and 1832 in Hatfield Broad Oak, 80 of them (40%) were of children aged 10 or under. At the other end of the scale, it shows also that only 20% of those buried reached what we would now consider as old age, i.e. over 60.

A lot depended upon the individual incumbent as to whether he was disposed to record additional information. From May 1827, the new curate at Hatfield Broad Oak, John Robert Hopper, took it upon himself to start recording in the margin the cause of death of those he was burying and other information besides. So, we find that a serious epidemic of typhoid carried off 25 children between September 1828 and June 1829, reaching a peak in January and February 1829 (below).

In 1830, it was measles that took 6 children in March and April and in 1831, 4 children died of whooping cough. Throughout the period, 4 infants died of convulsions.

Typhoid, an indicator of impoverished and unhygienic living conditions, seems to have been a major cause of death during the period, with 37 cases, followed by a condition described rather vaguely as ‘decline’ which accounted for 23 deaths. A few died of consumption or of ‘inflammation of the bowels’ or of dropsy. One 52 year old died of cancer in 1832. Two were simply found dead in their beds and one woman aged 27 was found dead in a field on Sunday 30th March 1831 – the verdict that she died of apoplexy.

Occasionally, a fatal accident is recorded as the cause of death. In November 1828, a 64 year old Edward Bird ‘fell thro’ 2 floors of Mr P Sullivan’s malting, Heath and died a day or 2 after’. Another died in July 1832 of ‘old age arrested by a fall down stairs’. In May 1830, one Patterson Parker ‘accidentally shot himself’.

Later that same year in July, a Royal Naval Lieutenant, George Berkley Love, visiting from Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight, was working in the Park of Barrington Hall when he ‘accidentally cut himself thro’ the lower third of the thigh with a scythe’ and bled to death in 5 minutes. J. R. Hopper records that an oak tree was planted soon afterwards to mark the spot where the accident occurred.

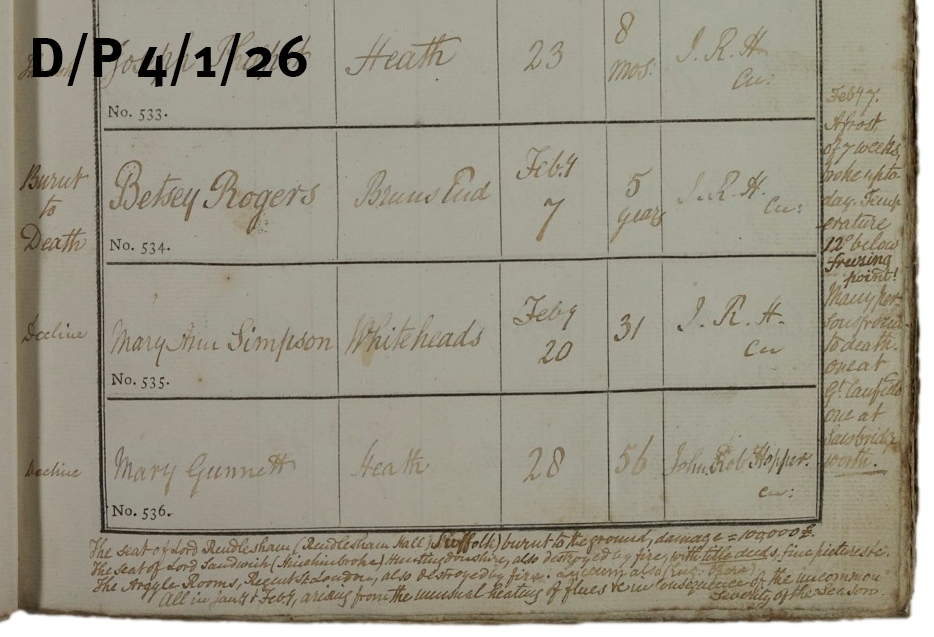

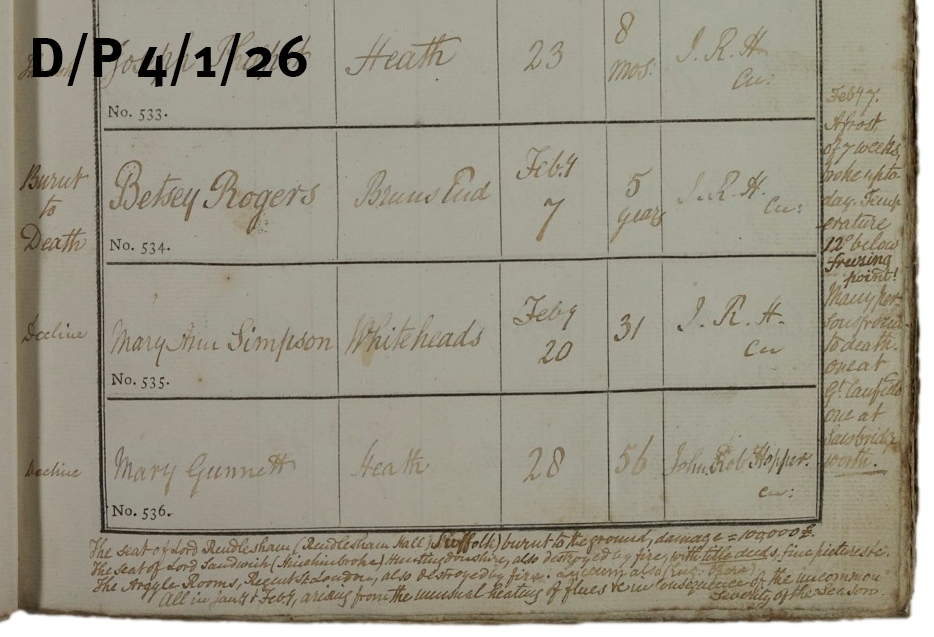

Earlier that year in February, poor little 5 year old Betsy Rogers burnt to death, and two extraordinary marginal notes on that page give a clue as to how (below):

Feb.y 7. A frost of 7 weeks broke up today. Temperature 12° below freezing point! Many persons frozen to death. One at Gt Canfield, one at Sawbridgeworth.

The seat of Lord Rendlesham (Rendlesham Hall, Suffolk) burnt to the ground, damage = 100,000£; The seat of Lord Sandwich (Hinchinbroke, Huntingdonshire) also destroyed by fire with title deeds, fine pictures, etc.; The Argyle Rooms, Regent St, London also destroyed by fire. Lyceam also…All in Jan.y in Feb.y arising from the unusual heating of flues etc. in consequence of the uncommon severity of the season.

If you would like to find out more about parish registers and how they can help you with your research, come along to our next Discover: Parish Registers workshop on Thursday 12 March 2015, 2.30pm-4.30pm. Tickets are £10.00, please book in advance on 033301 32500. Full details can be found on our events page.

If you are interested in booking a talk with one of our Archivists, on parish registers or another subject, please get in touch with us on ero.enquiry[@]essex.gov.uk

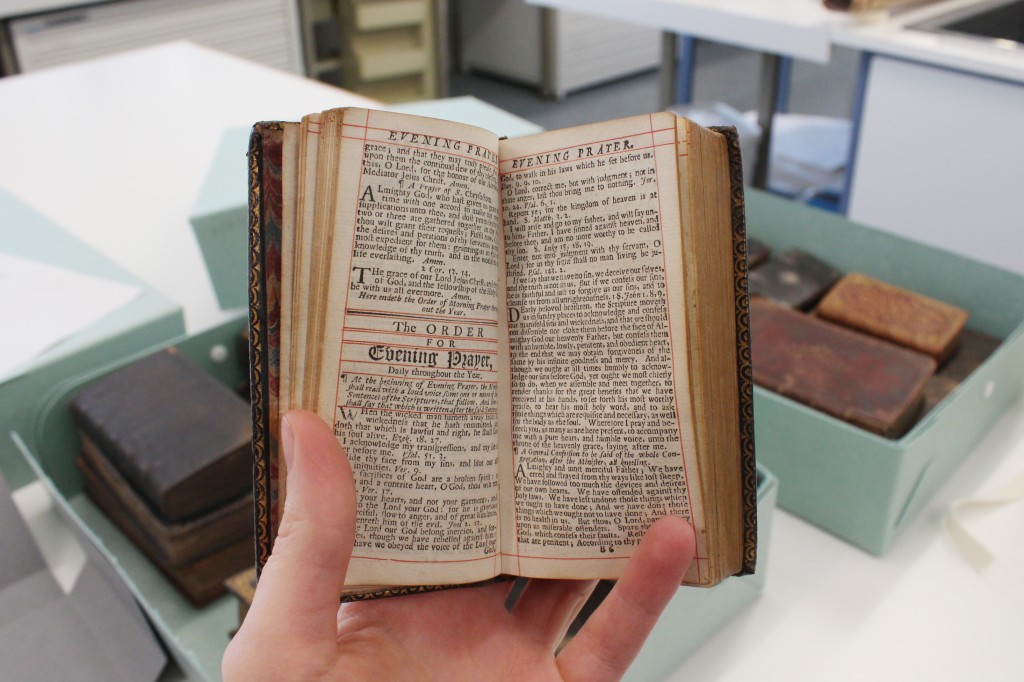

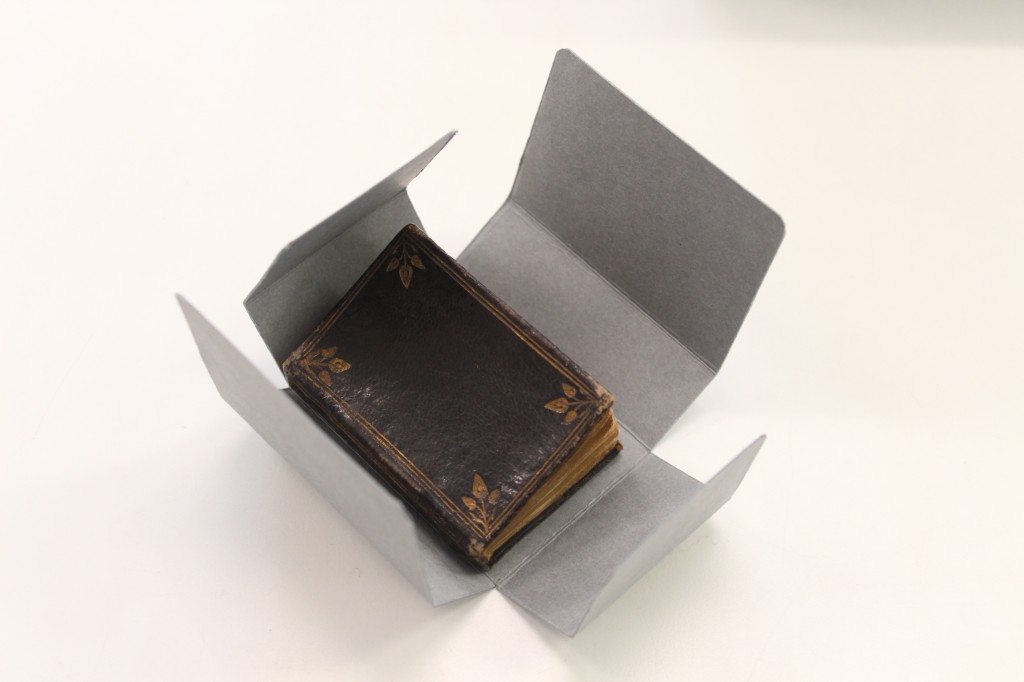

I happen to like things in miniature, so my eyes were quickly drawn to this prayer book, which is one of the smallest in the collection, and contains correspondingly tiny type. It has now had a special folder made for it to give it some extra protection when stored back in its box.

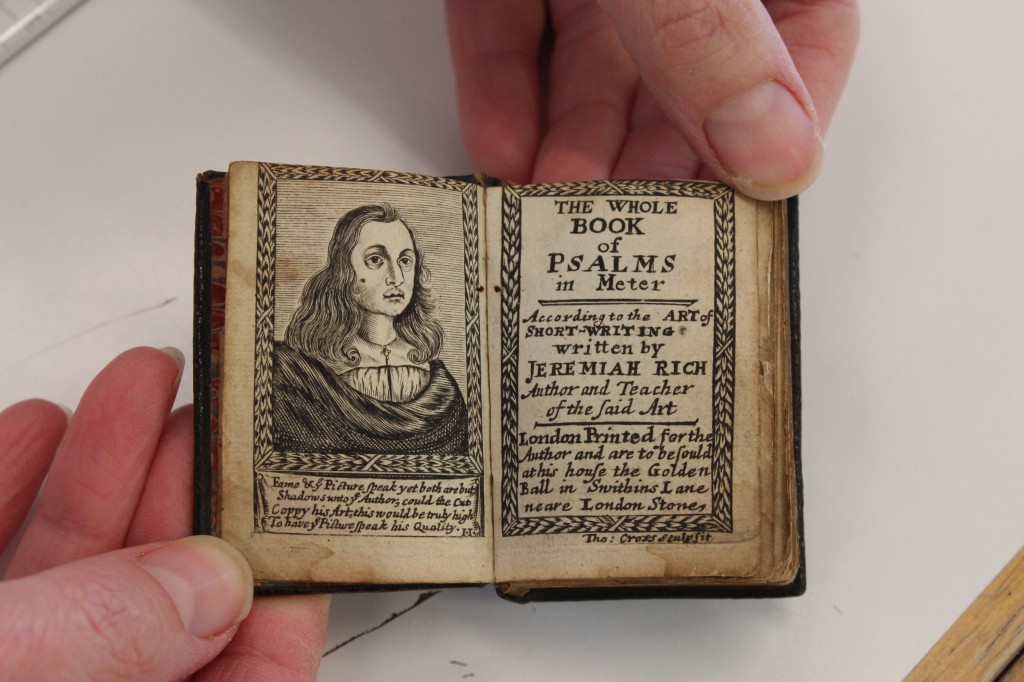

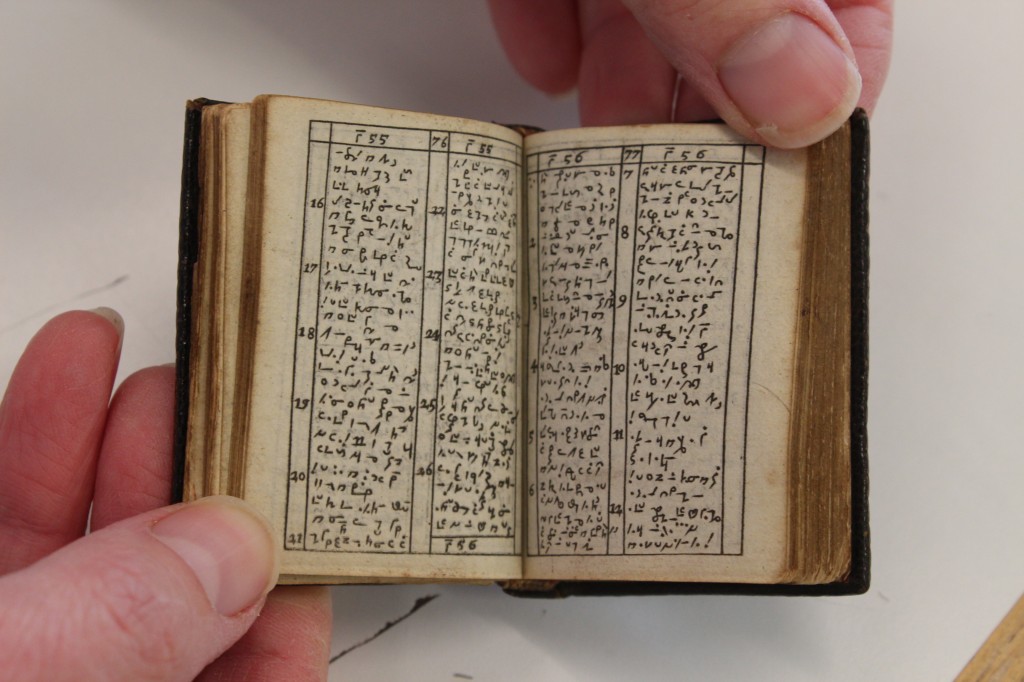

I happen to like things in miniature, so my eyes were quickly drawn to this prayer book, which is one of the smallest in the collection, and contains correspondingly tiny type. It has now had a special folder made for it to give it some extra protection when stored back in its box. It is a book of psalms written in a kind of shorthand developed by a man named Jeremiah Rich.

It is a book of psalms written in a kind of shorthand developed by a man named Jeremiah Rich. If you are a fan of books, why not join one of our bookbinding workshops to make your own book using traditional techniques? The next course begins on 2 March 2015 – details can be found on our events page.

If you are a fan of books, why not join one of our bookbinding workshops to make your own book using traditional techniques? The next course begins on 2 March 2015 – details can be found on our events page.

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the