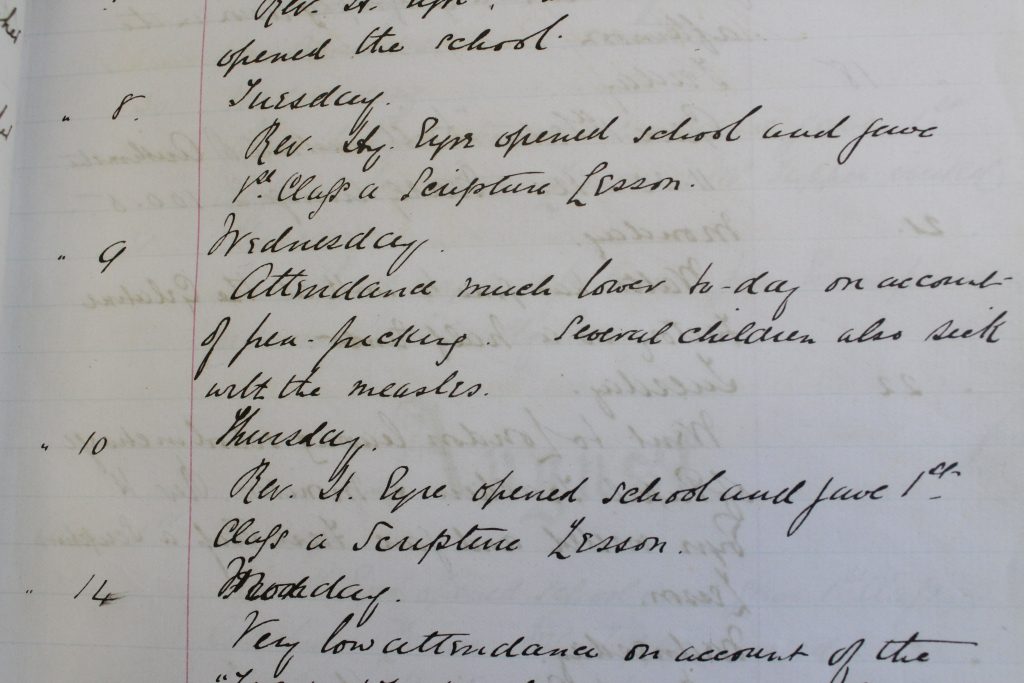

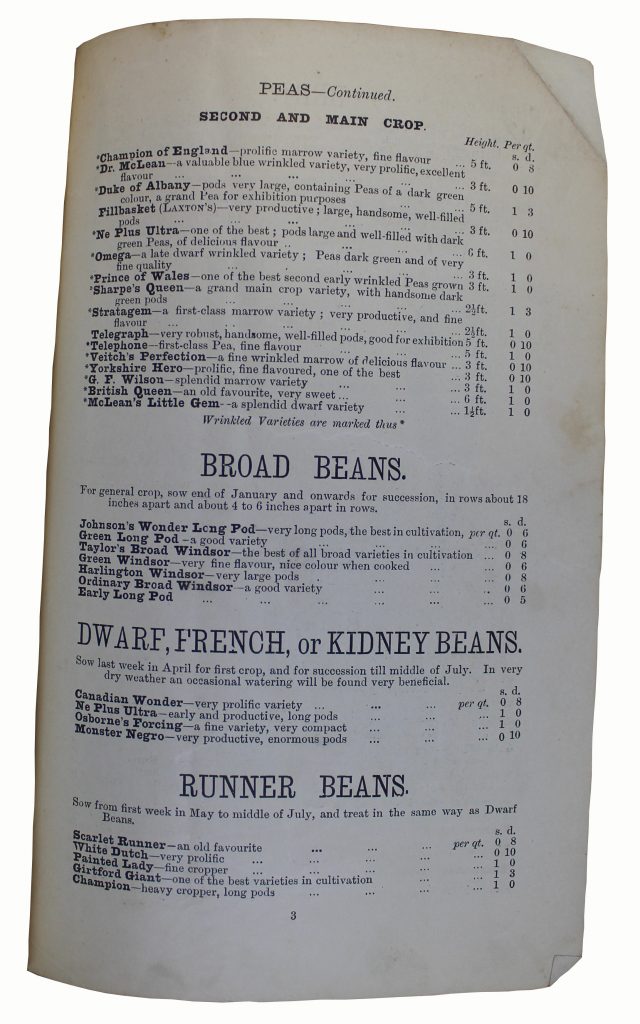

Crops of every kind, including peas, were tempting targets for humans as well as natural predators, such as rabbits but mainly birds. Extensive acreages of field crops posed a challenge to protect, but an abundance of cheap human labour would have provided at least some form of bird-scaring by children armed with clappers and loud voices. Fortunately for the farmer, this was an easy job that required little skill and not much, if any, payment.

A story passed down in my family is that my great-grandfather, Henry Wiffen (1862-1946), was taken out bird scaring as one of his first jobs, presumably when he was 7 or 8. His father lit a little fire in the base of a hedge for him to keep warm by while keeping an eye out for birds. This might have been at Nightingale Hall Farm in Halstead / Greenstead Green. See George Clausen’s painting, ‘Bird Scaring – March’.

For those levels of society that could afford to have large, planned gardens, with an appropriate number of gardeners, then there was plenty of people on hand to protect crops from predation. However, that fickle, enigmatic element known to all gardeners, the weather, had also to be countered. To begin with a warm wall or sheltered corner of a garden might suffice to an aspiring gardener. Small moveable enclosures, known as cloches, or cold frames with a covering of ‘lights’, could be used to give protection to particular plants or small areas of crops. If you were rich then money, and lots of it, could be thrown at this problem, and, as with all things, technology evolved over time along with the aspirations of the owners of grand houses. They were the early adopters of even greater resource-intensive infrastructure, and a good example of this can be seen in the incredible, and now lost, gardens of Wanstead House.

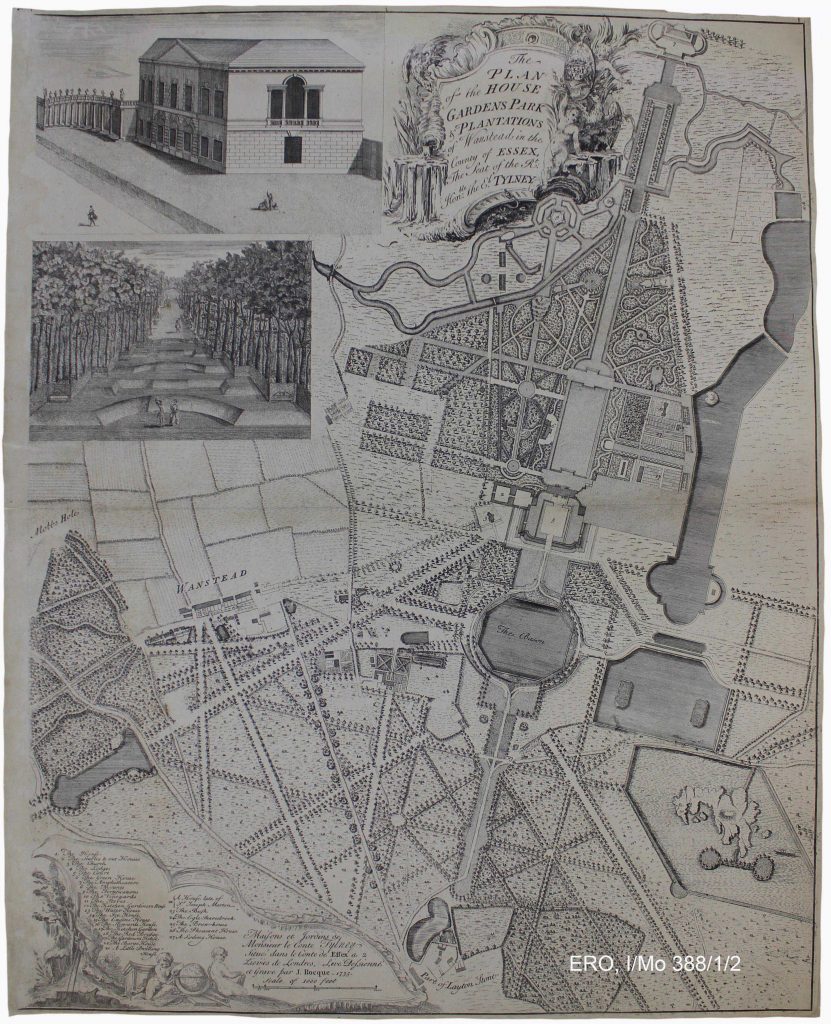

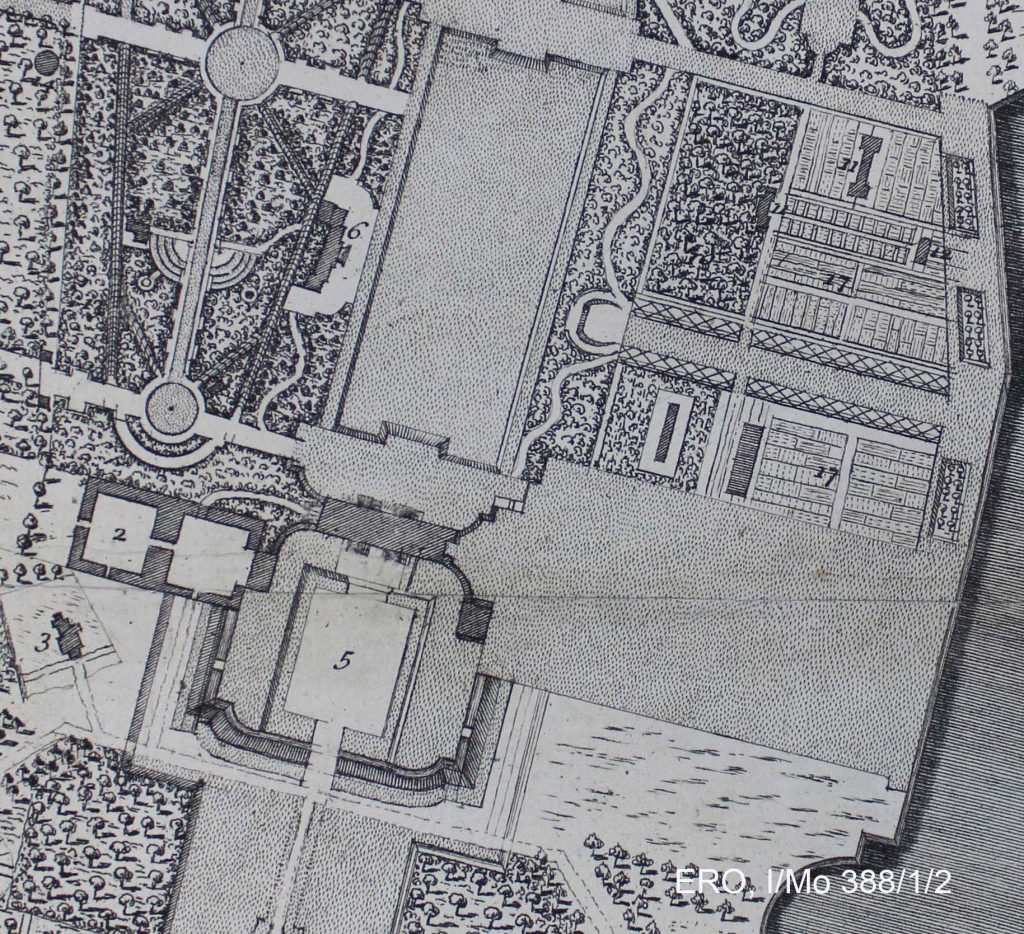

The plan of the house gardens park & plantations of Wanstead in the county of Essex, the seat of the Rt. Honble the El. Tylney. (ERO, I/Mo 388/1/2, 1735)

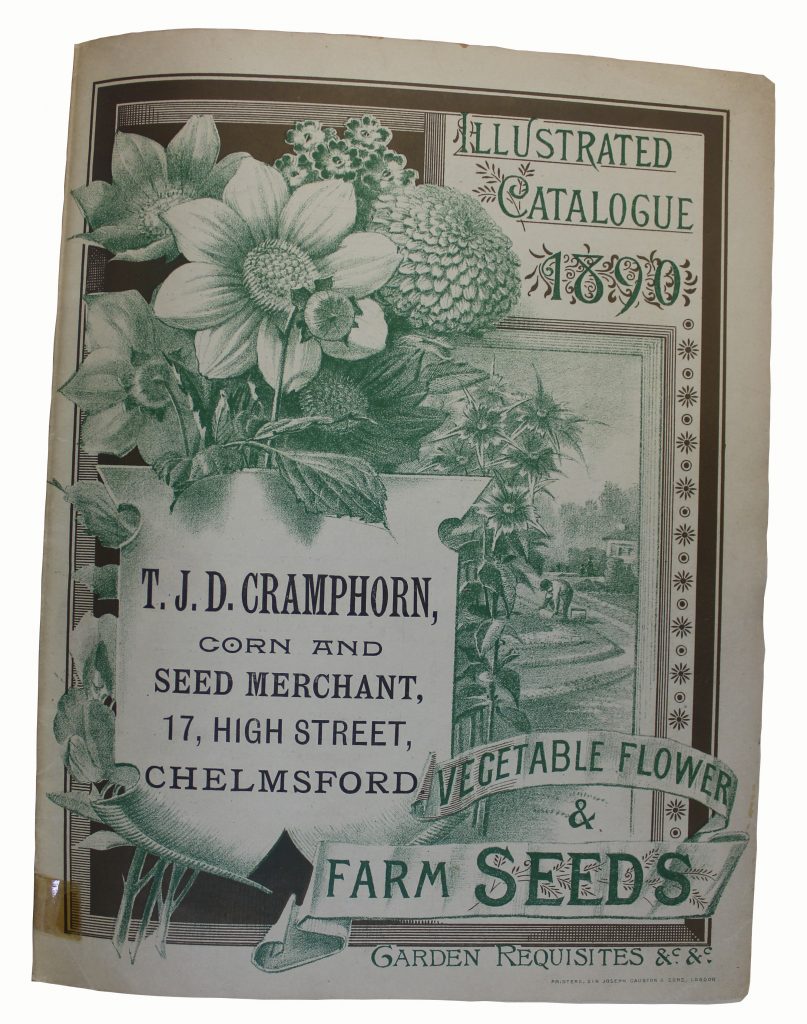

A vitally important part of a planned garden was the kitchen garden, for in an age before global trade and refrigeration only a very small amount of produce was imported. So if you wanted to eat something out of the ordinary then you had to grow it, and if you wanted to eat that something out of season then you had to make it happen. The wealthier you were the more you could eat out of season fruit and vegetables, such as peas and peaches, and the more exotic would be the produce that your gardens grew – pineapples being the most unusual and difficult to grow (the first grown in Britain is reckoned to have been in 1693 for Queen Mary II: T. Musgrave, Heritage Fruits & Vegetables (London, 2012), p.193). Grapes were also a symbol of status and perhaps the most famous vine is the 250 year-old Black Hamburg at Hampton Court Palace, which has an interesting Essex connection (see: https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/whats-on/the-great-vine/#gs.2k24uk). Kitchen gardens then, were both a symbol of wealth and status as well as a practical contributor to the household economy. At Wanstead the extensive gardens were located close to the main house.

As can be seen, the kitchen gardens are on a grand scale and laid out in a very formal manner with lots of beds and borders. From these would have been grown all the run of the mill fruit and vegetables that would have fed the household throughout the year. These gardens were powered by the extensive use of manure, as often as not horse manure, to provide the soil with the necessary body to produce large yields. As can be seen from the plan, the stables are quite close but on the opposite side of the house from the gardens. This would have entailed the carting of manure across the sightline of the house or a very long detour to get it to the gardens out of sight. Wherever practical the stables and gardens were, sensibly, located adjacent to one another and quite often out of view altogether so as not to offend the owner and his family with sights and smells that might not be conducive to their sensibilities. It could be that at Wanstead we are looking at an early form of that relationship and that by the nineteenth century the layout of an estate had become more nuanced. A good example of a recreated kitchen garden and stable set-up is at Audley End (http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/organic-kitchen-gardens/)

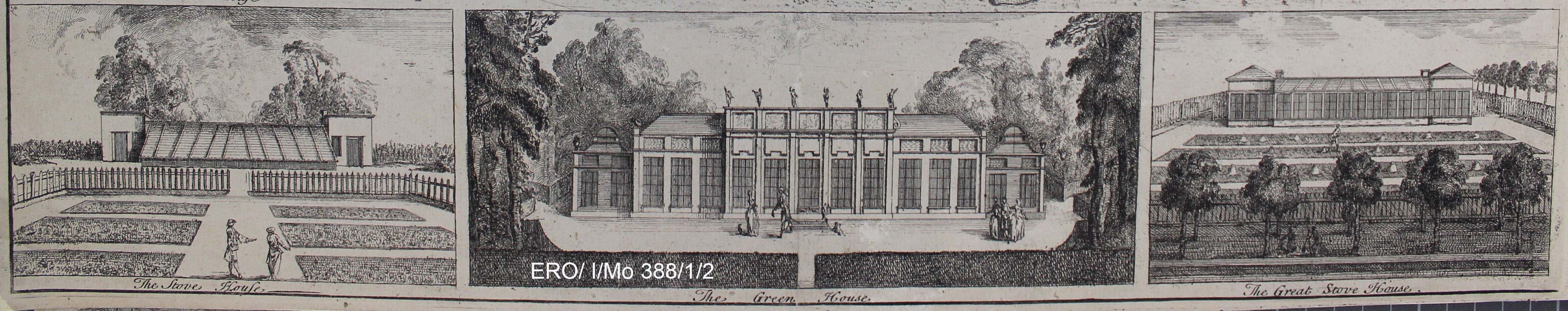

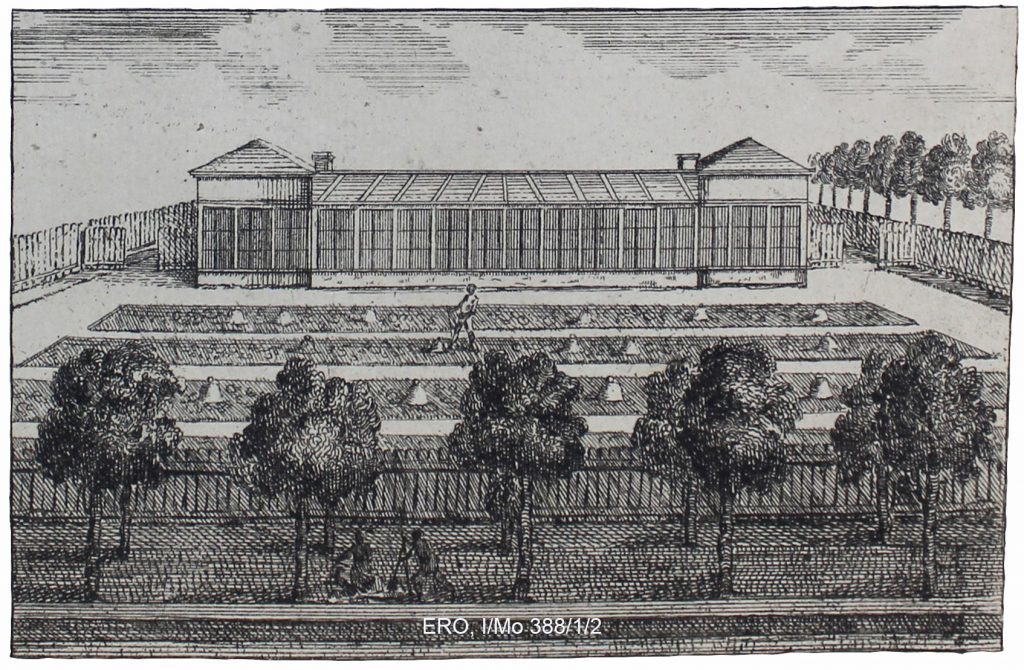

Having sheltered open borders was all very good but in order not only to grow tender plants, but to extend the season of more general crops, then much more intensive infrastructure was required. This is highlighted on the 1735 plan of Wanstead with individual depictions of a green house (6 on the plan) and two ‘stove’ houses (both marked as 11 on the plan). A greenhouse at this stage was a light, airy building with some glazing that sheltered plants, while the stove house was much the same but had heating of some kind, often free-standing stoves located within the building. We think of greenhouses today as having minimal structure and maximum glazing, but this design only came around in the second half of the nineteenth century as developments in cast-iron production and the decreasing cost of glass made the ‘modern’ greenhouse possible. The eighteenth-century equivalent had much more structure and far less glazing, very much like what we would think of as an orangery. As indicated above, these were very expensive to build and run.

While the gardens at Wanstead House were obviously cutting-edge, they also deployed other techniques for growing fruit, vegetables and flowers. If we look at the image of the Great Stove House we can see a couple of examples. Firstly this sub-section of the garden is surrounded by what appears to be wooden fencing. Not only does this define the area, but the fencing also gives protection from damaging winds thus creating a sheltered micro-climate. In a later period, brick walls were built which fulfilled the same functions as a wooden fence but also had the advantage of acting as a structure up which plants could be trained – tender ones on the south facing walls with hardier ones on the cooler, north facing walls. Some of these walls were built to be heated themselves by fireplaces and flues to protect crops from frost, think outdoor radiators – but they must have been extremely expensive to run. Not all plant protection at Wanstead was very expensive, for in the borders are bell-shapes which are probably glass cloches, a low-tech form of plant protection. Cloche being French for bell – hence they get their name from their shape.

Cloches and cold frames were available to a wider cross-section of the population than expensive greenhouses. For example, Richard Bridgeman (d.1677) had 18 ‘cowcumber’-glasses worth 9 shillings, while Theophilus Lingard (d.1743/4) had, among extensive possessions, 20 bell glasses and two cucumber frames. (F.W. Steer, Farm and Cottage Inventories of Mid-Essex, 1635-1749 (Chelmsford, 1950), pp.145, 270.) So for gardeners of all degrees there was some form of artificial plant protection available to give that little bit of advantage when growing crops. A more modern version of the traditional bell cloche was the Chase barn cloche, introduced in the early twentieth century by Major L.H. Chase. These simple forms of protection were used in their thousands by nursery and market-gardeners to give protection to their crops from the bad weather. However, they were susceptible, along with greenhouses, to the rain of shrapnel that was caused by anti-aircraft fire during the Second World War – thank goodness we don’t have that to worry about now!

While no longer bell-shaped, protective covers are still known as cloches, although it is thought that in Essex most market gardeners of the post-war years pronounced cloche as CLOTCH (sounding like BLOTCH) – no subtleties in pronunciation there! (Photo: N. Wiffen)