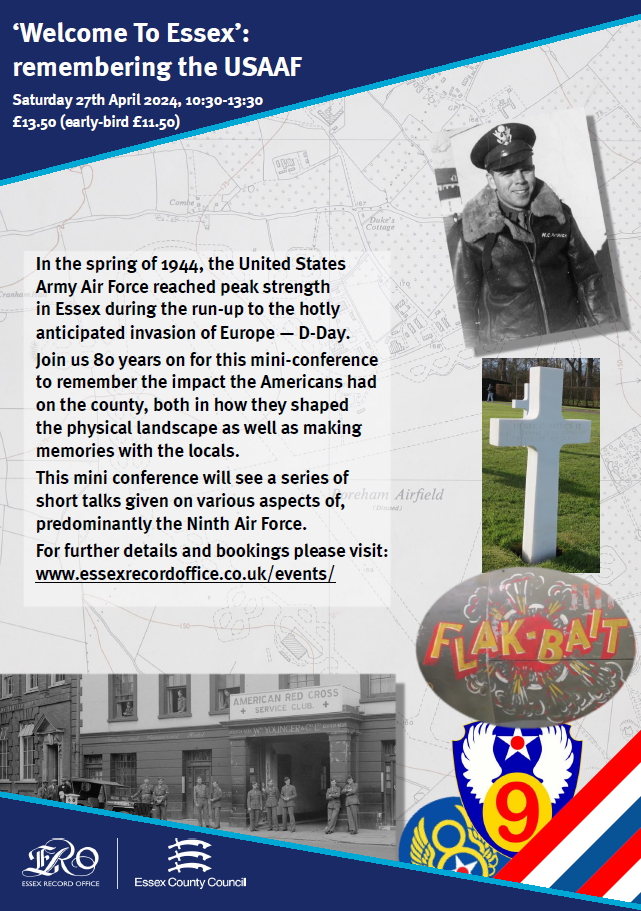

Tickets are selling fast for our forthcoming event, ‘Welcome to Essex’: remembering the USAAF.

The Saracens Head in Chelmsford (Now ‘The Garrison’) was used as the American Red Cross Service Club.

In the spring of 1944, the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) reached peak strength in Essex during the run-up to the hotly anticipated invasion of Europe — D-Day. Week after week new units of the USAAF flew into recently constructed airfields across the county, to start participating in the air campaign against the Luftwaffe and German coastal defenses. Small, rural villages across Essex became the center for many hundreds of American servicemen to descend on, to look at the ancient architecture as well as go in search of a pint of warm English beer! For the locals their quiet roads were filled with unsurpassed numbers of trucks and Jeeps buzzing around, ferrying men and material about the countryside. Overhead the air was filled with aircraft, Mustangs Thunderbolts, Flying Fortresses, Liberators, Havocs and Marauders, and many a morning was interrupted by the thunderous sound of hundreds of thousands of horsepower engines warming up.

Join us 80 years on from these momentous times for this mini-conference to remember the impact the Americans had on the county, both in how they shaped the physical landscape as well as making memories with the locals. Remembrance w ill be a theme running through the event, the date on which it is being held being of particular significance to one of the speakers in relation to one of those Americans who flew out of Essex.

ill be a theme running through the event, the date on which it is being held being of particular significance to one of the speakers in relation to one of those Americans who flew out of Essex.

This mini conference will see a series of short talks given on various aspects of,

predominantly, the Ninth Air Force, although mention will be made of the Eighth as well

– there’s just so much to discuss!

For further details and bookings please visit: www.essexrecordoffice.co.uk/events.

Reduced price ‘early-bird’ tickets are available If you book before mid-day on March 14th – don’t dilly-dally as tickets are selling fast. We look forward to seeing you there.