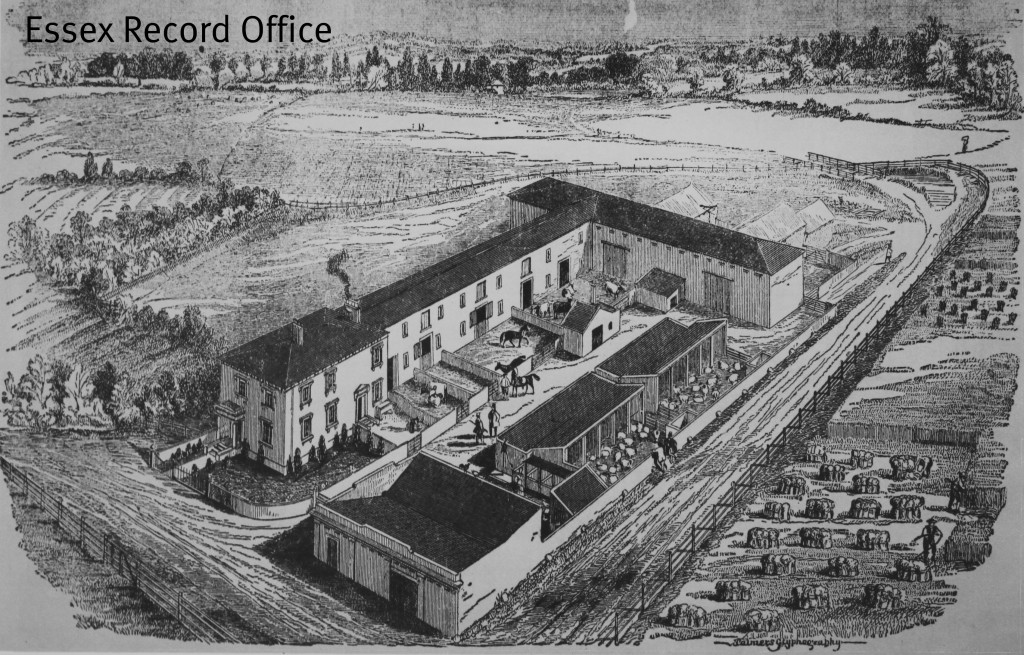

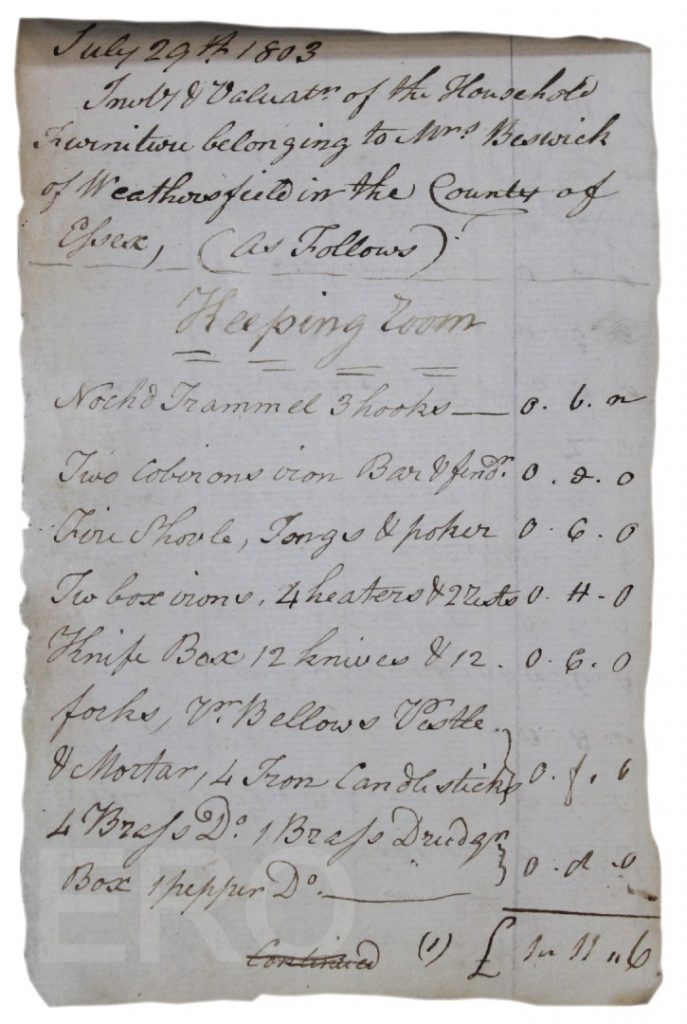

Visiting the Searchroom can be a dangerous business – you can be looking for one thing and find yourself fully distracted by something else. Such as finding a full farm inventory when you were only trying to research crop rotations and the incidence of the growth of turnips…

A Wethersfield farm inventory of 1803

The culprit for this particular distraction was an impressively detailed entry in a 19th century valuer’s notebook for Wethersfield Farm (D/DF 35/1/4). Friend and user of Essex Record Office, Dr Michael Leach, discusses this interesting entry.

Inventories (usually prepared for probate purposes) give a unique room-by-room view of how the interiors of houses in the early modern period were arranged and furnished, as well as clues to the affluence and style of living of their occupants. By the end of the eighteenth century, they are much fewer in number and rarely adopt the useful room-by-room listing which provides so much insight. So it is particularly illuminating to find one which provides the full details, dating from 1803. This particular one was prepared for estate, rather than probate valuation, purposes.

Arrangement of Rooms

The standard medieval house comprised a hall, with a parlour at high end and a buttery at the opposite end, with chambers over the parlour and buttery. Later additional chambers were provided when a floor was inserted into the double height hall. The extra rooms so created were used for storage, as well as for sleeping. At farmhouse level, kitchens were unusual and, though they increasingly appeared over the seventeenth century, cooking was often still carried out over the open fire in the hall. However, it is perhaps surprising to see this pattern continuing into the early nineteenth century in an obviously affluent household.

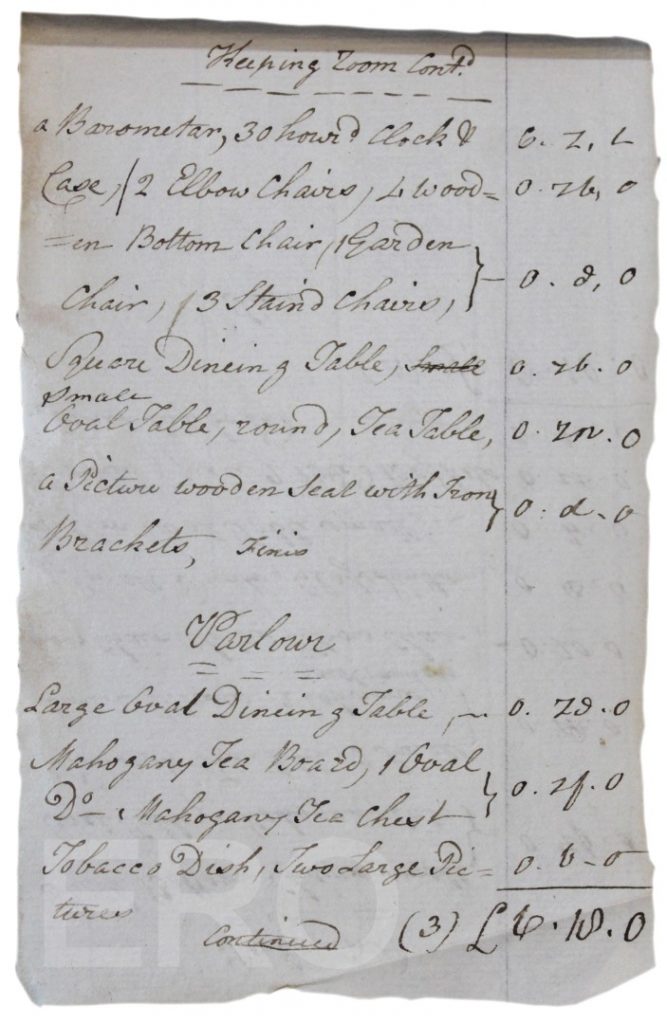

Hall: In this Wethersfield farm, the medieval arrangement persisted as late as 1803, though the hall was renamed the ‘keeping’ room; a term that I have not met elsewhere. The Wethersfield farm was still doing all of its cooking in the hall which was the only room provided with the essential cobirons to support the spits, and the ‘nocked trammel’, an adjustable chain in the chimney for suspending cooking vessels over the open fire. However most of the cooking utensils (spit, saucepans, skillets, frying pan, dripping pans, ladles and so on), as well as the tableware and drinking vessels, were kept in the two butteries. As is usual with inventories, it is not possible to deduce where the food preparation took place. The Wethersfield hall, with its square ‘dining table’, pewter mugs and at least ten chairs, was used for eating meals, as well as cooking them.

Parlour: This room was also used for meals with a large oval dining table and six chairs. It also had a number of smaller tables, and a ‘tea chest’ and was perhaps used for more ‘polite’ entertainment. It was also furnished with two large pictures and seven small prints and included a fireplace with cobirons (but no other cooking equipment). The two linen horses suggest it was also used for drying clothes. The level of sophistication of this household is shown by the ownership of an ‘iron footman’, a device used to keep plates warm before serving food.

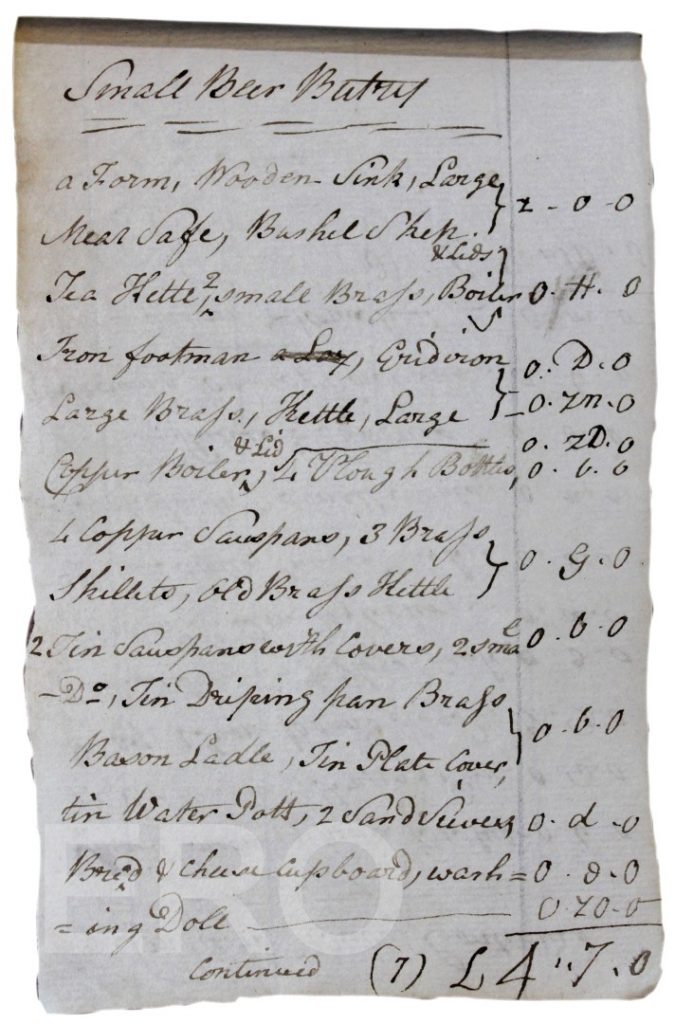

Butteries: Provision of separate butteries for strong and small beer was common by the seventeenth century and is still found at Wethersfield. Only the strong beer buttery served its named purpose, albeit on a substantial scale (five hogsheads, four half hogsheads and two 20 gallon barrels – a total capacity of nearly 400 gallons, though some, of course, must have been empty).

This buttery was also storing cutlery, dishes and mugs, and was equipped with a sideboard and shelving. The small beer buttery had a sink, shelving, a few more barrels and most of the cooking equipment – and an ironing board. It also had a meat safe, so may have used for food storage as well. Neither room appears to have been heated, or to have had a table which would have been necessary for food preparation.

Chambers: None appear to have been heated by fireplaces. It is assumed that these chambers were either upstairs (a staircase is mentioned) or over some of the subsidiary offices outside the main core of the house. There were five in total, one of which (the cheese chamber) was used exclusively for storing and maturing cheese (10 old and 24 new cheeses were listed). The other four chambers were furnished as bedrooms, one of which (the menservants’ chamber) slept two in stump beds. These were probably for the annually hired farm servants, rather than for domestic ones. Two other chambers (‘best’ and ‘small’) had four poster beds, mahogany or walnut furniture, and curtained windows. The ‘spare’ chamber had a sacking bottom bedstead but was furnished with chairs, a dresser and various chests and boxes – but no curtains.

Domestic offices: These consisted of brewhouse, dairy, cream house, mealhouse, granary and cornchamber, all appropriately equipped for their named function. Only the brewhouse had evidence of a fireplace, equipped with a nocked trammel.

Wealth and Status of the Occupants

Compared to typical farm inventories of a century earlier, the number and quality of possessions is striking, including a 30 hour clock and barometer (which would have been mercury, as the aneroid was yet to be invented) in the hall, as well as walnut and mahogany furniture elsewhere. Oak is now limited to more utilitarian purposes.

There is a plethora of table ware including ‘Queensware’, a cream-coloured earthenware which had been developed by Josiah Wedgewood in the 1760s. Pewter plates have entirely replaced wooden ones, and there is a surprising amount of tinware, presumably manufactured in the industrial Midlands.

The spare chamber contained ‘a Lot of Books’, so the household was a literate one. Two large pictures hung in the parlour, and some other rooms had prints on the walls.

Two of the bedrooms were curtained but no carpets or rugs were listed, so the floors were probably bare. Most striking, though, is the very large quantity of ‘stuff’ which had been bought or acquired. But, in spite of this level of sophistication, food was still being cooked and eaten in the hall over the open fire; exactly as it would have been several centuries earlier.

Farming methods and its products

It is surprising that no animals are listed, though it is clear that this was principally a dairy farm. Also there is none of the normal farm equipment such as carts, and ploughs with their necessary tackle, though the listing of two scythes and five sickles suggests that a crop, or hay, was harvested. There was only one sack of wheat in the granary at the end of July – this may have been bought in for domestic use.

Cheese making seems to have been the main activity, with 10 old and 24 new cheeses in the cheese chamber. The cheese making indicates the need for quantities of milk, but where were the cows, and where were they being milked? Was the necessary milk being bought in, or were the animals excluded from this inventory for some reason?

Bee-keeping was a subsidiary, but not insubstantial, activity with at least 14 skeps listed. These were made of straw and were destroyed at each harvest, so this total might represent the number of colonies that were being used for honey production.

The other significant activity on this farm was brewing which seems to have been on a much larger scale (and a level of equipment, including an ‘iron furnace’) than normal household consumption would justify.

Conclusion

For the historian inventories provide a unique opportunity for a virtual tour of houses at various periods, as well as offering much information on the level of wealth and sophistication of the occupants. It is much to be regretted that most Essex probate inventories were destroyed but fortunately those of Writtle, a peculiar of New College, Oxford, have survived in the college archives and were published in full (with an invaluable commentary and glossary of archaic terms) by F W Steer as Essex Record Office Publications No. 8 in 1950, Farm and Cottage Inventories of Mid-Essex, 1635-1749.