Karen Dunn, a student at the University of Essex has explored the story of one almost forgotten Suffragette who just happens to have lived in Finchingfield!

The Suffrage Movement was so much more than the Pankhurst’s – Emmeline, Christabel, Sylvia – and Millicent Fawcett. These are the names that instantly pop up when the word ‘suffragette’ is typed into Google; their names have been indelibly written in history, but what about the foot soldiers? Who were the thousands of women who stood shoulder to shoulder, many of whose names we shall probably never know?

One such women is Gertrude Mary Ansell (1861-1932), a successful businesswomen, she ran a typing bureau, she was an animal rights activist, secretary or treasurer to more than one animal society, and a member of the Fabian Women’s Group.

Gertrude joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1906, she was forty-five years old. Her support of the Suffrage Movement, acts of militancy, arrests, hunger strikes and force-feeding remain relatively unknown, but her and thousands of women like her suffered these indignities for their cause. Gertrude’s own experience of the business world convinced her that women needed political freedom or their economic position would remain inadequate.

In February 1907 Gertrude joined a peaceful march organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, it was normal for women from other societies to march together, and in the same month she took part in WSPU demonstrations in Caxton Hall. By October 1908, Gertrude had become militant; she took part in a ‘raid’ on the House of Commons, and was arrested and sentenced to one month in Holloway Prison. In December 1908, dressed in her prison clothes, Gertrude joined other WSPU members to heckle David Lloyd-George at a Women’s Liberal Association meeting at the Albert Hall.

Gertrude continued to support animal societies. However, she promised at least one animal society that she would not take part in any militant suffrage action while working on the Dogs Exemption Bill and the Plumage Bill. Both of these acts were defeated in the House of Commons in the summer of 1913; Gertrude immediately began militant action.

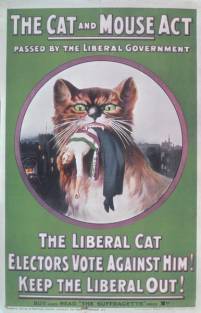

On the 2 August 1913 Gertrude began a one month’s sentence in Holloway Prison for smashing a window in the Home Office; she immediately began a hunger strike and was released under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’.

Gertrude somehow managed to avoid being arrested again to complete her sentence, but seeing as how she was finally re-arrested on 30 October 1913, outside Holborn Tube Station selling copies of the Suffragette; it can safely be assumed that she was not trying too hard!

Gertrude immediately began another hunger strike, and was released; she was re-arrested on 18 November 1913, and began another hunger strike; she was released again but this time managed to avoid re-arrest until 19 January 1914 and again went on hunger strike; this toing and froing between internment and release for suffragettes was why the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act became known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’.

On 12 May 1914, Gertrude visited the Royal Academy and attacked a picture of the Duke of Wellington with an axe. She was sentenced to six months imprisonment, and again, she immediately began a hunger strike. Despite not being released on this occasion she maintained her hunger strike which led to her being forcibly fed.

Gertrude was released from prison on 10 August 1914 under amnesty at the outbreak of the First World. She had been forcibly fed two hundred and thirty-six times. The WSPU gave women who went on hunger strike medals, silver bars were added for every hunger strike undertaken in prison, and the enamel bars represented periods of force feeding.

During the war, militant campaigning was suspended; the Pankhurst’s and Fawcett all supported the war effort. When the war was over, some women were given the vote, but not all. Gertrude Ansell would have been one of the women who received the vote. It would be another ten years before all women became eligible to vote.

After 1918, there is very little to be found out about Gertrude, she never married, she moved to Finchingfield, Essex and following an operation for gall stones, died in Saffron Walden General Hospital on 7 March 1932. There can be no doubt that women would one day have the vote, but without the likes of Gertrude Mary Ansell, and thousands of women like her, it would have taken a lot longer to achieve.

It is women like Gertrude who are the ‘unsung heroes’ of the Suffragette Movement and who deserve to be remembered for their sacrifices to the emancipation of women.