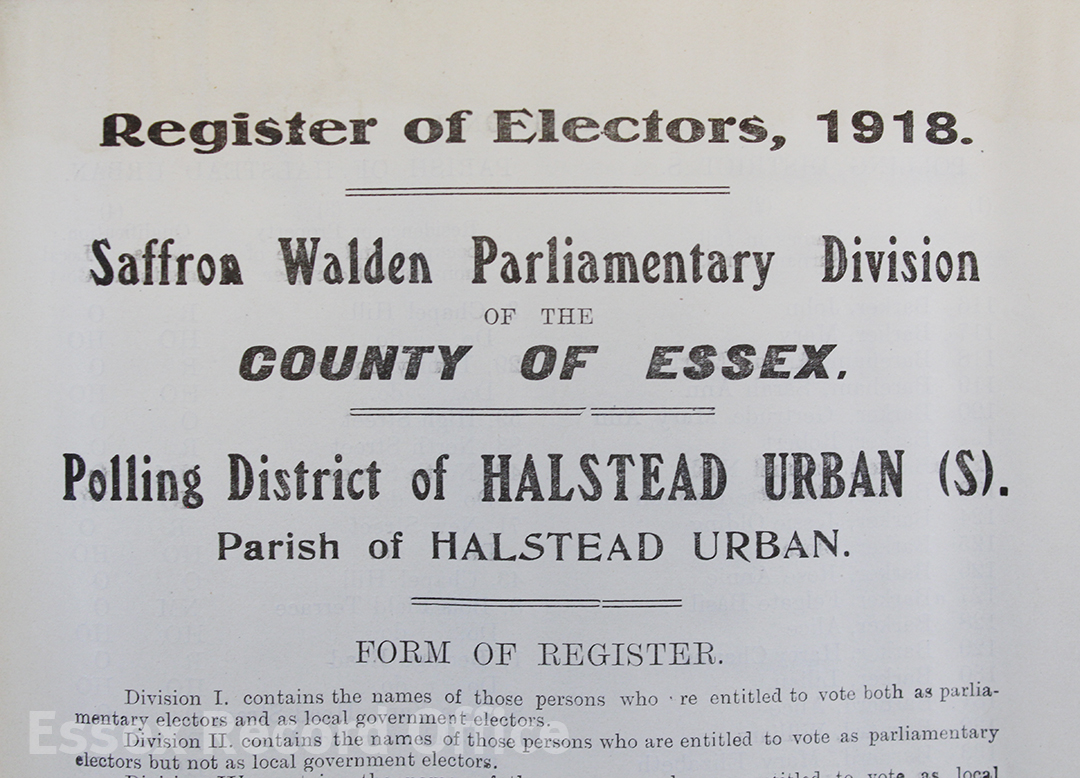

6 February 2018 marks 100 years since some UK women were granted the right to vote in parliamentary elections, after decades of campaigning.

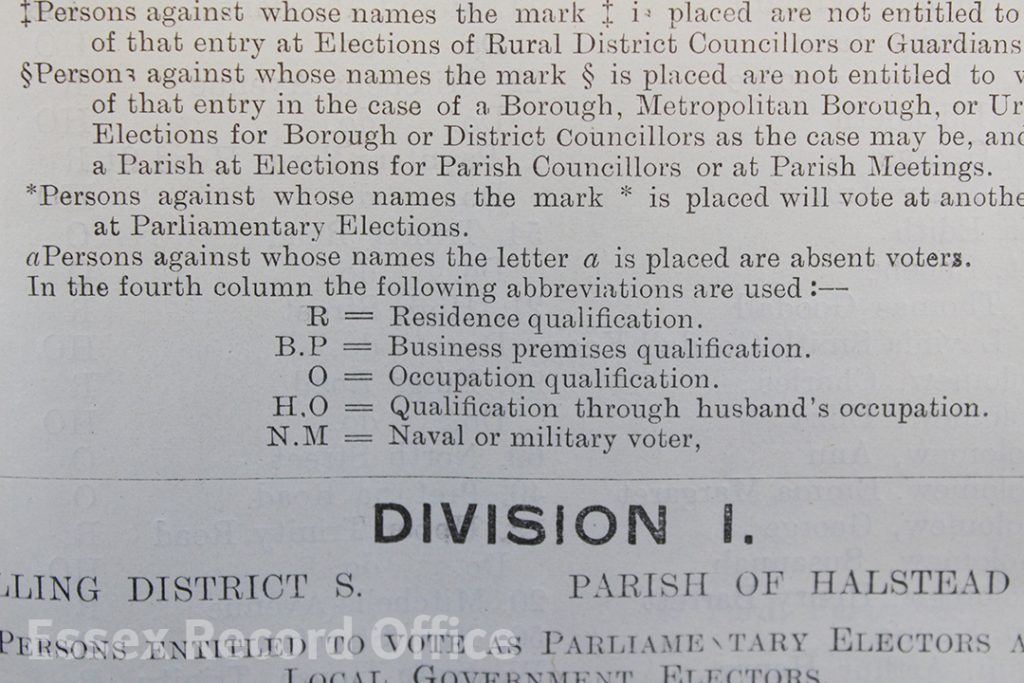

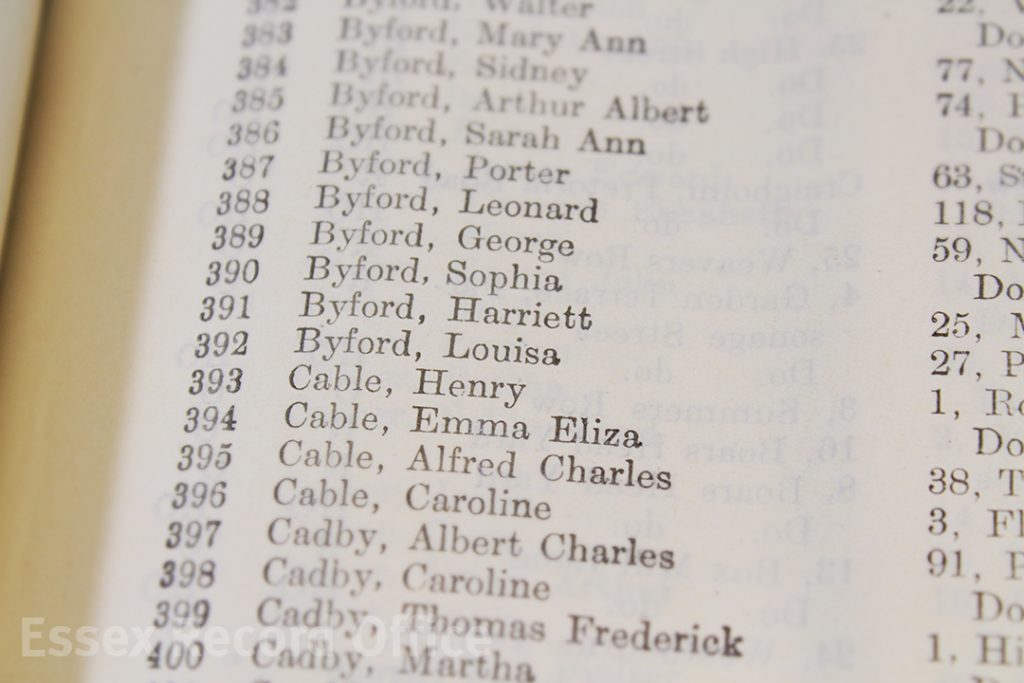

The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the right to vote to women over 30 who met a property qualification – 8.4 million women in total. With so many men having been killed in the First World War, there was a fear that if equal voting rights were given female votes would outnumber male voters, and the country would end up with a ‘petticoat parliament’.

(It’s also worth noting that before the Act, only 60% of men over 21 had the right to vote. This meant that many of the men returning from military service would not have been able to vote. In addition to granting the vote to women, the Act also extended it to all men over 21, an additional 5.4 million men.)

The campaign for votes for women had stretched over decades, and for most of that time made little progress. In this blog post we take a look at some of the local women and men who took part in this momentous national campaign.

Lilian and Amy Hicks – Great Holland

Photographic postcard of Lilian Hicks, produced by the Women’s Freedom League (D/DU 4041/1)

Lilian Hicks (née Smith) was born in Colchester in 1853. She married Charles Hicks, and they made their family home at Great Holland Hall near Frinton-on-Sea. From the 1880s, when she was the mother of young children, Lilian worked for the women’s suffrage movement, organising meetings across East Anglia, and when she was older her daughter Amy joined Lilian in her campaigning. They belonged to various suffrage organisations over the years, joining the militant WSPU in 1906 before breaking away with the more peaceful Women’s Freedom League (WFL) in 1907, then ultimately rejoining the WSPU. Mother and daughter were arrested together on 18 November 1910 at the protest which became known as Black Friday, a struggle between campaigners and police in Parliament Square which turned violent.

Amy took part in the WSPU window smashing campaign in March 1912, and was arrested and sentenced to four months hard labour. She spent time in Holloway and Aylesbury prisons, including time in solitary confinement. She was one of the suffrage prisoners who went on hunger strike, and was subjected to the brutal procedure of forcible feeding.

Read more about Lilian and Amy Hicks in our previous blog post about them

Dorothea and Madeleine Rock – Ingatestone

Sisters Dorothea and Madeline Rock of Ingatestone, left and centre. The caption on the back of the photograph does not tell us which sister is which, or the identity of the third woman, although she may be their governess, Louisa Watkins. This photograph has been digitally restored. (T/P 193/13)

Sisters Dorothea and Madeline Rock of Ingatestone both spent time in prison for their campaigning activities. They were daughters of Edward Rock, an East India tea merchant, and his wife Isabella. Dorothea was born in 1881 and Madeline in 1884, and they had a middle-class upbringing, with a governess, a cook, and a housemaid employed in the household.

In 1908, the sisters both joined the WSPU, and in December 1911 both were sentenced to 7 days’ imprisonment for smashing windows. Undeterred, the sisters smashed further windows in March 1912, and were arrested with fellow Suffragettes Grace Chappelow, from Hatfield Peverel, and Fanny Pease. The four attended a hearing together, which heard that they had smashed windows at London’s Mansion House with hammers and stones. A newspaper account of the hearing reported Dorothea defending their actions:

‘This thing is not done as wanton damage – we have done it as a protest against being deprived of the vote.’

Kate and Louise Lilley – Clacton

Kate and Louise Lilley are welcomed back to Clacton after being released from prison in May 1912. The pair were met at the station then driven home in their father’s motor car (Clacton Graphic, 4 May 1912, photo from Hoffman’s Studio)

Sisters Kate (b.1874) and Louise Lilley (b.1883) were daughters of Clacton magistrate and company director, Thomas Lilley JP. They were also both members and officials of the Clacton branch of the WSPU. Like the Rock sisters and Amy Hicks, they took part in the March 1912 WPSU window smashing campaign and were sentenced to two months’ hard labour as a result.

They were released in early May, and returning home to Clacton they were ‘met with a most hearty welcome home from hundreds of spectators, including many women wearing the W.S.P.U. badge’ (Clacton Graphic, 4 May 1912). The crowd cheered the sisters, and they were presented with bouquets. The Graphic further reported that ‘Their suffering for the cause, which they believe to be right and just, have not damped their ardour, and they are more determined than ever to go forward’.

Kate herself wrote a piece for the Graphic about their experience, and why the sisters had taken the course they had:

‘I should like to state that the reason why my sister and I decided to take our courage in both our hands, and make a protest by damaging property was: – we were following the dictates of our conscience and our reason. We know we had to make an active protest to call attention to the need of the great and urgent reform and so long delayed Act of Justice, i.e., Enfranchisement of Women.’

On the hunger strike which took place while they were in Holloway, Kate could only write:

the horrors of it are still too fresh in my memory for me to feel able to dwell in any way on the details.

Eliza Vaughan – Rayne

The NUWSS pilgrimage which Eliza Vaughan took park in in July 1913 ended with a rally in Hyde Park address by their leader, Millicent Garrett Fawcett (photo from the Women’s Library at LSE)

Eliza Vaughan was born in Brixton in 1863. Her father was a vicar, and later moved the family to Finchingfield when he became vicar there. From 1895 Eliza lived in Rayne near Braintree, and researched and wrote about the local area.

Eliza was an active member of the National Union for Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) for many years. Unlike the WSPU, the NUWSS believed firmly in sticking to peaceful campaigning activities.

In July 1913 Eliza took part in a march organised by the NUWSS which brought together suffrage campaigners from across the country, all the contingents eventually meeting for a rally in London. On 25 July 1913 a letter from Eliza was published in the Chelmsford Chronicle explaining why the march was taking place:

‘The just end of this gigantic undertaking is to demonstrate to the nation throughout the length and breadth of England the dertermination of non-militant suffragists to obtain justice for their own sex, so that the needs of women, particularly the toilers in our great industrial centres, may be adequately represented in Parliament.’

Eliza was one of the leaders of the Essex contingent, beginning in Colchester and marching through through several town and villages including Mark’s Tey, Coggeshall, Braintree, Witham, Kelvedon, Chelmsford and Romford. The marchers included both men and women, and in each place they stopped they made speeches, distributed leaflets and had conversations with people about women’s suffrage. Throughout the march they took pains to distance themselves from the militant actions of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) led by Emmeline Pankhurst. The audiences at the meetings are described by Eliza as being mostly orderly, but the marchers were in places subjected to abuse and egg-throwing.

In an account of the march titled ‘Humours of the Road’ (T/Z 11/27) Eliza describes the march as a pilgrimage ‘journeying to a shrine, dedicated to Justice and Right’.

Rosina Sky – Southend

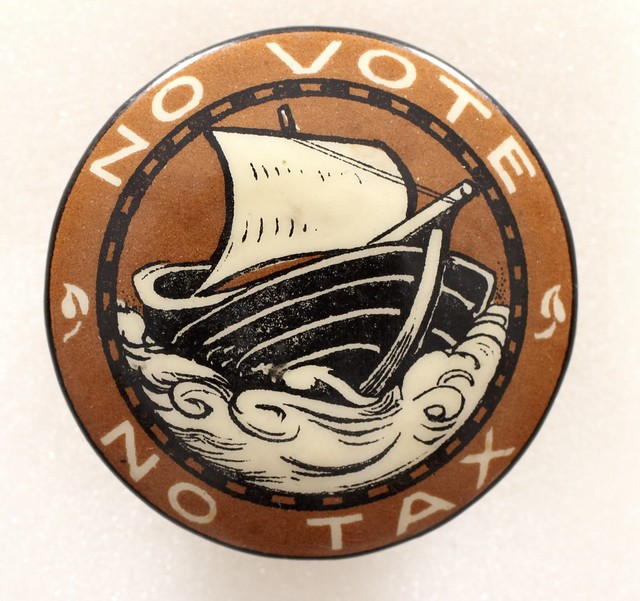

Rosina Sky led the charge for votes for women in Southend. She was born in Whitechapel in 1877, the daughter of a Russian tobacconist and pipe manufacturer. She married William Sky, and they had three children together, before divorcing. As a single mother of three, Rosina ran a tobacconists shop of her own in Southend at 28 Clifftown Road. As a woman in a man’s world, Rosina had all the responsibilities of running a business with none of the rights accorded to men in the same position. She was treasurer of the Southend branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), and a member of the Tax Resistance League, whose slogan was ‘No Vote, No Tax’. Their key argument was that it was unjust for women to pay tax when without a vote they had no say in how it might be spent.

In September 1911, bailiffs seized goods belonging to Rosina in lieu of the taxes she had refused to pay. The goods were publicly auctioned, accompanied by a parade of the WSPU in Southend to protest. Further goods were confiscated from Rosina and sold in June 1912. She continued to run her shop until her death in 1922.

________________________________________________________________

A small display of records relating to Essex suffrage campaigners from the ERO’s collections is currently on display in our Searchroom, until the end of April 2018.