Ruth Selman blogs for us about her research for her PhD ‘The Landscape of Poverty in Later Stuart Essex’…

Essex Record Office has just launched a small exhibition on poverty in Essex in the late seventeenth century which can be viewed in the Searchroom at Chelmsford. This is based on my research into the scale and nature of poverty in Essex between 1660 and 1700 for a PhD at the University of Roehampton. I am studying records held by Essex Record Office and The National Archives with the aim of identifying who was poor at that time and how the experiences of being poor differed within communities and across Essex as a whole.

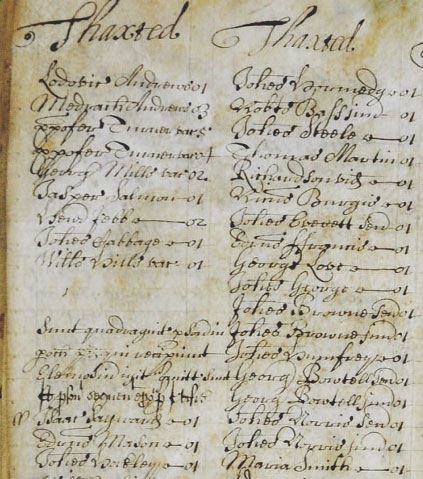

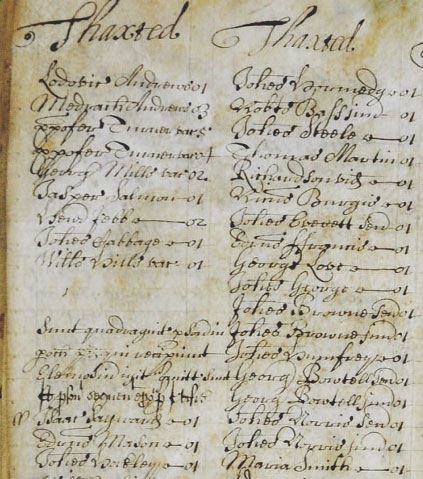

The records of the hearth tax, which mainly date from the 1660s and 1670s, give us a glimpse into the varied circumstances of Essex residents at that date. Every liable householder was required to pay a shilling for each hearth in their dwelling twice a year – at Lady Day (25 March) and Michaelmas (29 September). In an attempt to ensure that all revenue due to the Crown was collected, even those exempt from paying the tax were recorded in the returns. Exemption was granted to those who lacked the wherewithal to pay local church and poor rates, and to those who paid twenty shillings or less rent for their houses and whose goods were worth less than ten pounds. With three hearths or more, however, there was no avoiding the tax collector even if you met the other criteria.

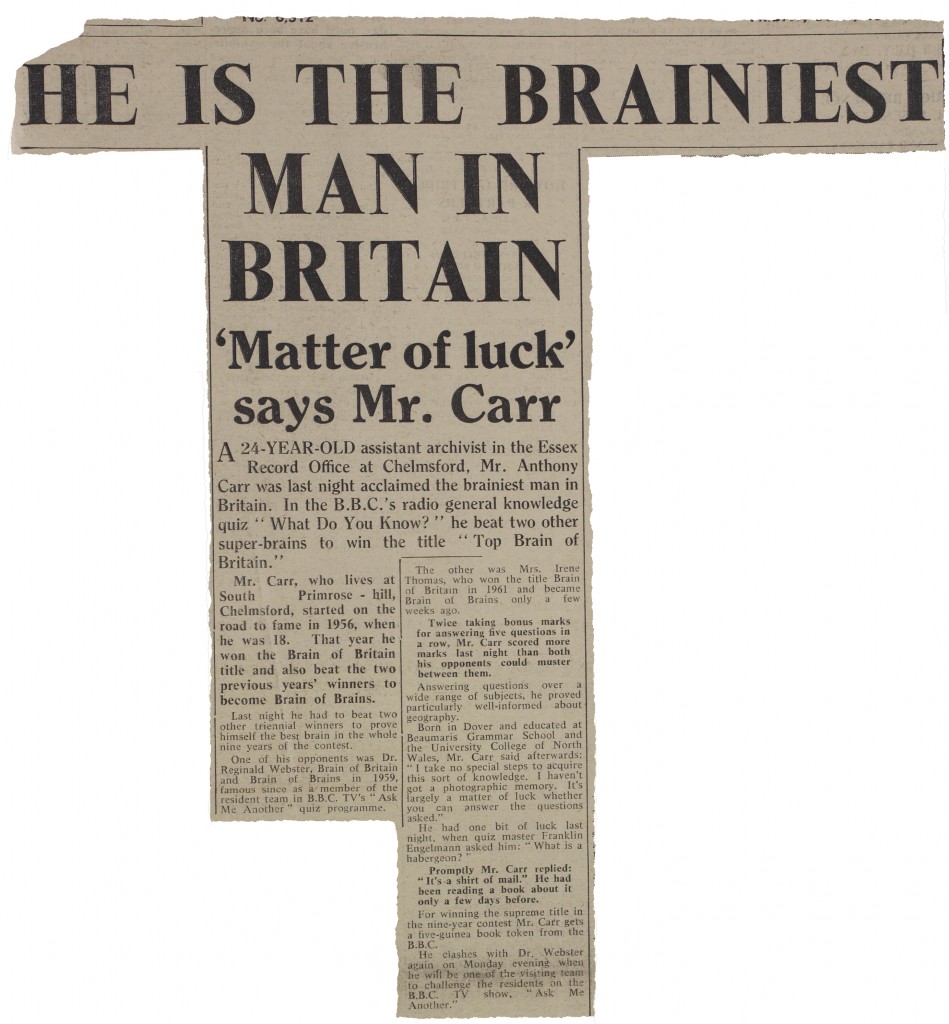

This extract from the hearth tax return for Michaelmas 1670 lists some of the householders in Thaxted and notes that there were also 40 people in receipt of alms (charitable payments or parish relief).

Q/RTh 5 – hearth tax return for Thaxted, Michaelmas 1670

The proportions of householders exempt from the hearth tax varied greatly across the county. The parishes closest to London tended to exhibit the lowest rates of exemption with an average of about 23%, possibly reflecting the relative prosperity brought by proximity to the London market. Those in the north and north-west of the county saw much higher exemption rates averaging about 63%. This may well have reflected the vulnerability of the many workers in the cloth industry who were based in that area. Interruptions to trade caused by wars, disease and local crises could result in a rapid change to dependent workers’ economic circumstances.

The Michaelmas 1670 hearth tax returns for Essex have been transcribed and analysed by the Centre for Hearth Tax Research at the Universityof Roehampton and are to be published this month by the British Record Society and a conference is being held to mark the launch. See http://www.hearthtax.org.uk/ for further details.

Comparing the lists of those exempt from the hearth tax with recipients of poor relief, recorded in the few detailed sets of accounts produced by overseers of the poor, provides us with greater detail about what poverty meant and how people survived. Support was provided to those unable to work by parish officers under the Poor Relief Act of 1601. The Act also required that the unemployed should be put to work on tasks such as spinning and that poor children should be apprenticed to learn a useful trade.

In practice,Essex parishes took different approaches to the problem of their poor depending on the particular local circumstances. Some poor, particularly widows, were paid regular pensions, although often the amount they were paid would have been insufficient without additional resources. In many cases, support was provided in kind, with clothing, fuel and food given directly to the poor. Sometimes the parish employed the poor to carry out odd jobs such as repairing the almshouse or digging graves. The care of orphaned and abandoned children often took up significant resources, with payments made to foster parents and the frequent supply of replacement clothing for their growing bodies.

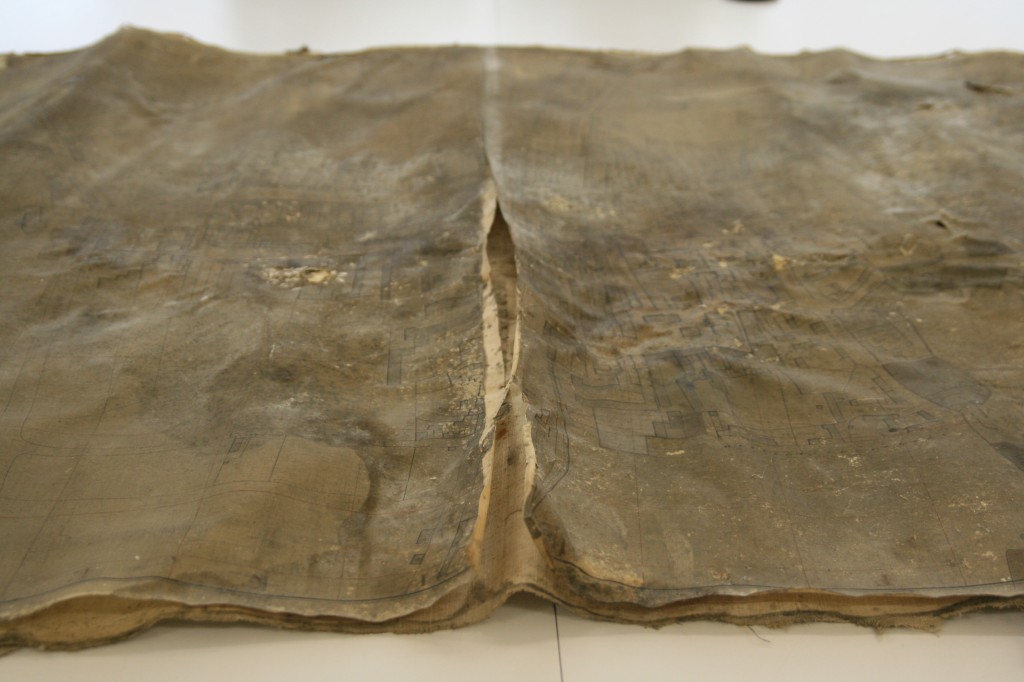

This extract from the accounts of the overseers of the poor of Barnston in 1671 shows a range of expenses incurred in support of the poor. A major expense derived from the last illnesses of husband and wife, Goodman and Goody Brown, with payments for nursing them and digging their graves (D/P 153/12).

The Barnston overseers reclaimed some of their expenditure by disposing of the household goods of the Brown family after their death, although there were some debts to pay with the proceeds. The inventory was recorded with their accounts (D/P 153/12).

The list of goods suggests the Browns were not destitute, but nevertheless they were unable to survive in their final months without support from the parish and their neighbours. They were not alone. It must have been a frightening existence, knowing that illness, disability, fire, flood or theft could result in dependence on parish relief and charity, often grudgingly given.

On that note, I am very grateful for the ungrudging funding awarded to this project by the Arts & Humanities Research Council and the Friends of Historic Essex and the help and support provided by Essex Record Office and The National Archives.

Find out more about the hearth tax records at The Hearth Tax in Essex, our first conference of 2012, on Saturday 14 July. See our events page for more information.