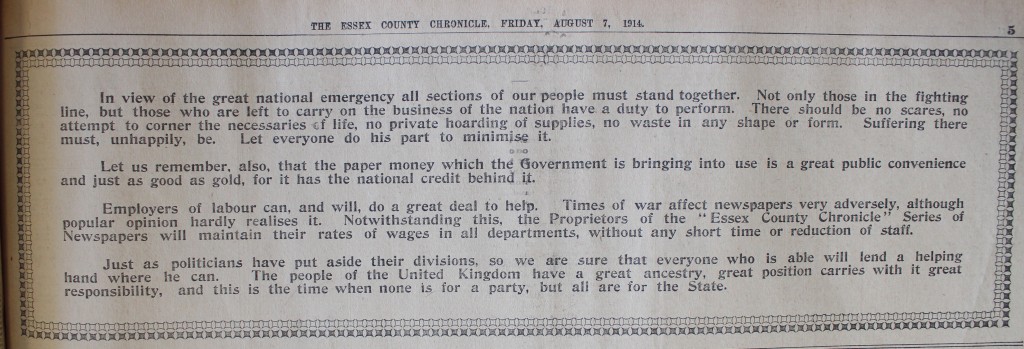

As the people of Scotland prepare to vote in the independence referendum, Archivist Katharine Schofield examines how Essex is able to claim a connection with Robert the Bruce, who from 1306 became King Robert I of Scotland.

The Bruce or Brus family held lands in Writtle, Hatfield Broad Oak, Terling, Hatfield Peverel, Lamarsh and Southchurch from a grant made by Henry III in c.1237/8 to Isabel de Brus. She was the daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon (brother of Malcolm IV and William I of Scotland) and Matilda, the daughter of the Earl of Chester. Isabel’s brother John inherited the title of Earl of Chester from his uncle. When John died in 1237 the earldom reverted to the Crown, and today is one of the titles of the Prince of Wales. In compensation Henry III granted lands to his sisters and heiresses, one of whom was Isabel, wife of Robert de Brus, 4th Lord of Annandale (the great-grandparents of Robert the Bruce), who received various lands in Essex (if you get as confused with the genealogy in this post as we did, here’s a handy family tree).

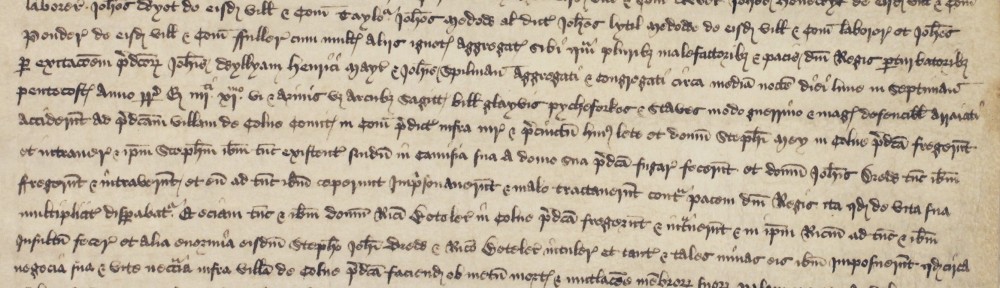

Among the earliest records in the ERO are records of the Brus family in Hatfield Broad Oak and Writtle. The deeds, although undated, almost certainly relate to Sir Robert de Brus, father of the future king of Scotland. Deeds of grants of meadow land in Hatfield Broad Oak of c.1280 and c.1300 (D/DBa T1/44, 50-51126, 157, 159) refer to part of the demesne meadow land of Sir Robert de Brus which adjoined the land being granted.

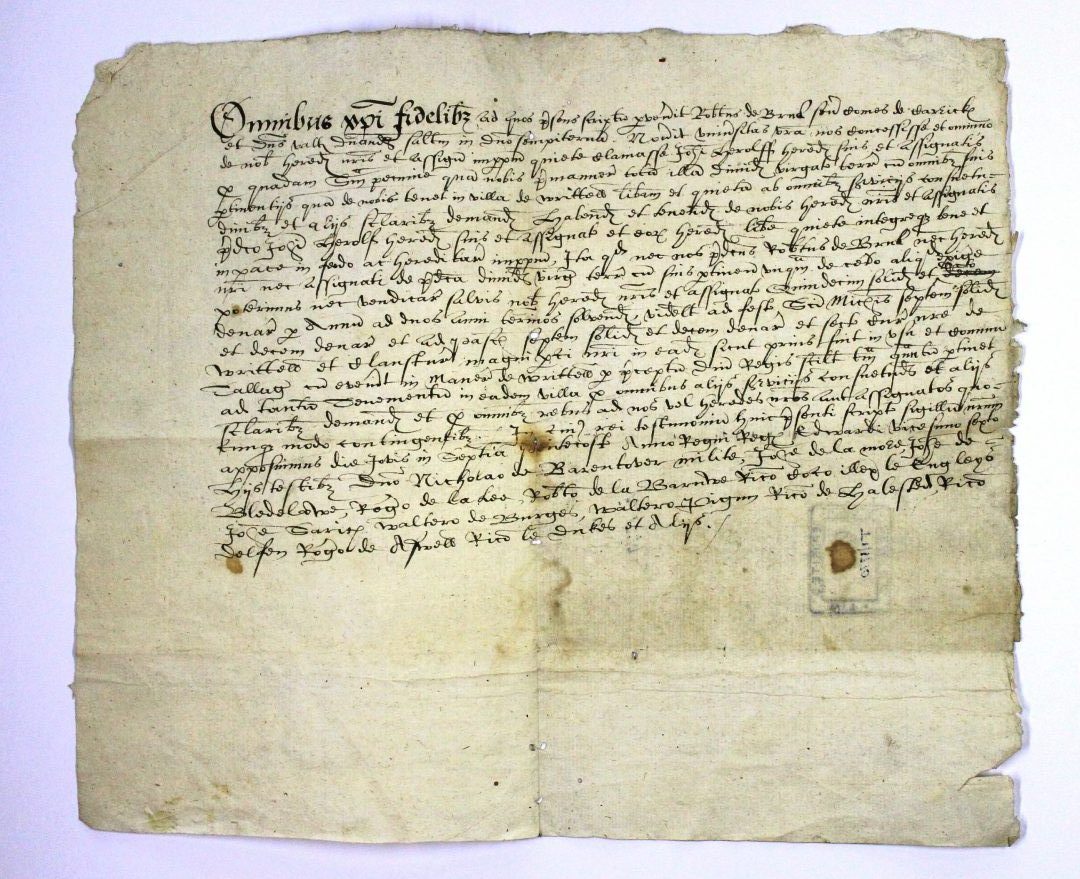

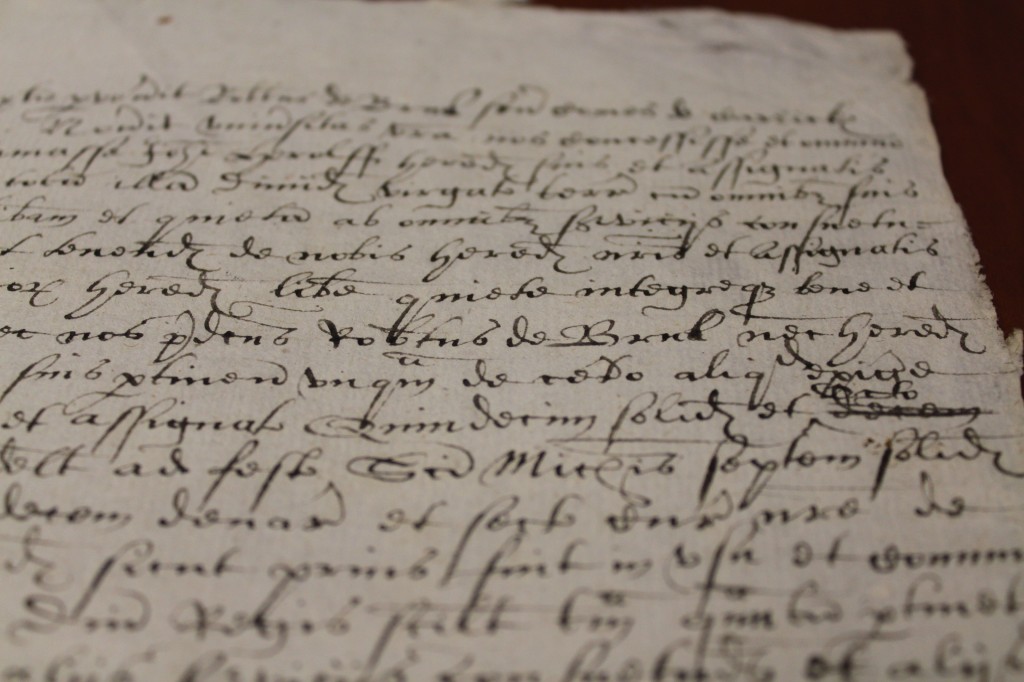

A release and quitclaim (renunciation of all future claims) which survives as a later copy was made on 22 May 1298 by Robert de Brus senior, Earl of Carrick, of half a virgate (approximately 30 acres) of land in Writtle to John Herolff (D/DP T1/1770). Robert de Brus inherited the earldom from his wife, and today this is another one of the Prince of Wales’ titles, which he uses in Scotland. Another quitclaim was made at Writtle on 4 August 1299 by Robert de Brus, described as lord of Annandale (dominus vallis Anandie) and lord of Writtle and Hatfield Broad Oak to Sir Nicholas de Barenton [Barrington] of 21 shillings annual rent for lands in Hatfield Broad Oak (D/DBa T2/9).

D/DBa T1/4 – This seal which belongs Sir Robert de Brus and shows the saltire or St. Andrew’s Cross, now an integral part of the Scottish flag.

In about 1295 Sir Robert de Brus, Earl of Carrick, exchanged 5½ acres of land in Hatfield Broad Oak for 5¾ acres held by Hatfield Priory (D/DBa T1/4). Brus’s seal survives on this deed and shows the saltire, still used today on Scotland’s flag, with a lion above. The seals of Scottish nobility began to include the saltire or St. Andrew’s Cross from the late 13th century.

When Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286, his four year old granddaughter, Margaret, the Maid of Norway, was the closest heir to the Scottish crown. She died in 1290 in the Orkney Isles en route to Scotland, leaving no obvious successor and Edward I King of England was asked by the Guardians of Scotland, who had been appointed to govern during the minority of the queen, to arbitrate between the many different claimants to the throne in what became known as the Great Cause. There were 15 claimants, including Edward himself, but the two main claimants were two great-grandsons of David, Earl of Huntingdon (a grandson of David I, r.1124-1153): John Balliol, grandson of David’s daughter Margaret, and Robert de Brus, grandson of Isabel, Margaret’s younger sister (again, this family tree helps!).

In 1292 Edward I selected John Balliol, who had the best claim. However, Balliol proved an ineffectual king and in 1296 Edward I took the opportunity to invade Scotland. Having defeated the Scots at Dunbar, he deposed Balliol, took over the throne of Scotland and removed the Stone of Scone, which was used for the coronations of the Scottish kings, to Westminster. The Scots fought back and the following year William Wallace defeated the English at Stirling Bridge. Battles and guerrilla warfare followed.

In 1304 the Sir Robert de Brus, mentioned in the Essex documents, died and his son more commonly known as Robert the Bruce inherited his father’s claim to the throne. At Brus’s death he held the manor of Writtle from the king for half a knight’s fee and the manor in Hatfield Broad Oak for another half. Feudalism meant that all land was held from the Crown in return for military service, the provision of a knight. Land that was held for one knight’s fee meant that Brus had to supply a knight (or sometimes the monetary equivalent) to the King for military service.

On 25 March 1306 Robert the Bruce was crowned king of Scotland at Scone. As a result all his English lands were attainted or forfeited to the Crown. The majority of the lands were later granted by Edward II to Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Essex.

There is one final reference to the Brus family in an extent (description of landholding) of the manor of Writtle dating from c.1315, possibly relating to the grant to de Bohun. This describes free tenants of the manor who held land from deeds of the lord Robert de Brus [per cartam domini Robert de Brus], who is further described as father of the present lord King [pater domini Regis nunc est].

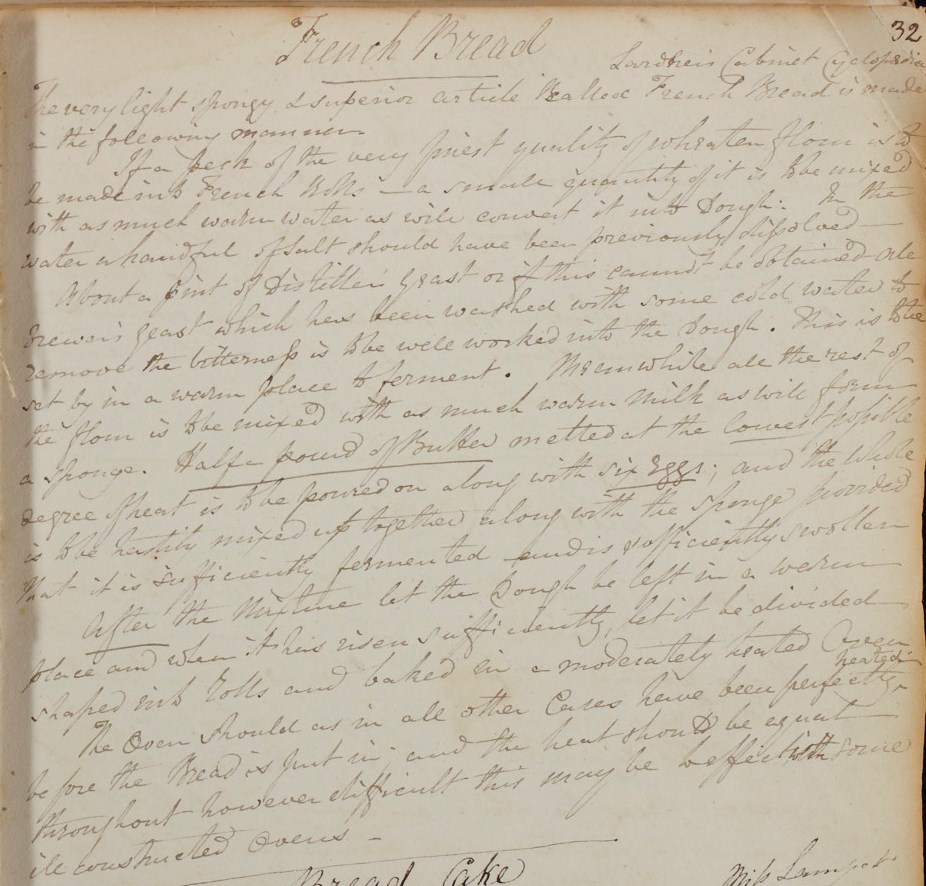

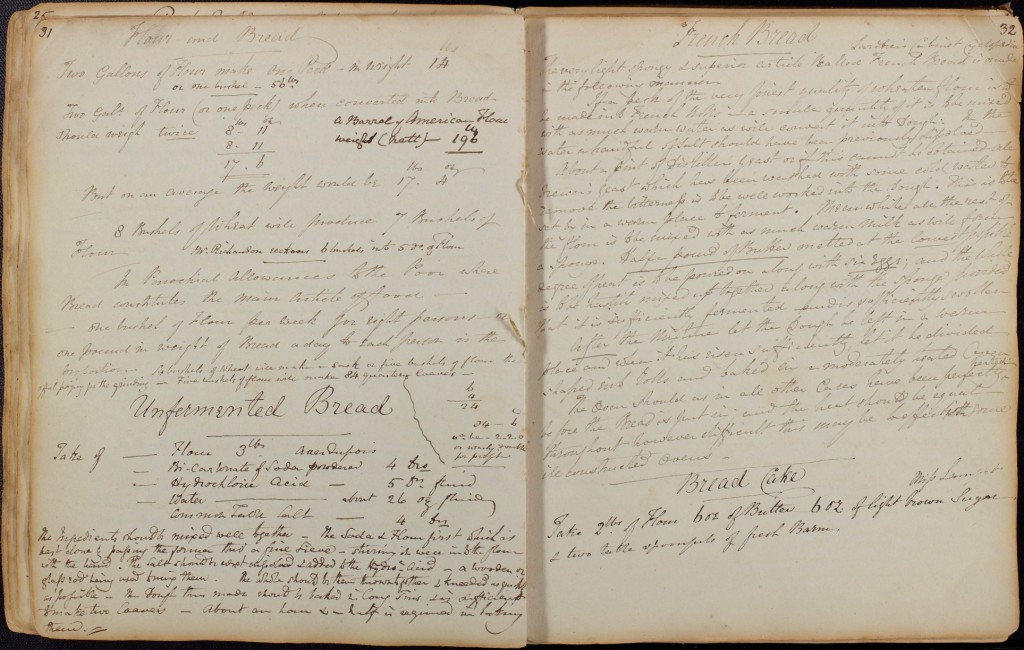

![T/B 677/2 - Unfermented Bread Take of –Flour 3lbs averdupois -Bi-Carbonate of Soda powdered 4 dram -Hydrochloric acid – 5 drams fluid -Water- about 26oz fluid -Common Table Salt – 4 drams The ingredients should be mixed well together – The Soda & flour first which is best done by passing the former thro[ugh] a fine sieve – stirring it well into the flour with the hand. The salt should be next dissolved & added to the Hydro[chloric]-Acid – a wooden or glass rod being used to mix them. The whole should be then thrown together & kneaded as quick as possible – The Dough thus made should be baked in long Tins and is sufficient to make two loaves – about an hour & a half is required in baking them.](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/T-B-677-2-a.jpg)