We love wills here at ERO. These fascinating and incredibly useful documents can tell us all sorts of things about the lives of people in the past, and are a brilliant resource for genealogists and social and economic historians alike.

The majority of the population did not leave a will, but where these documents exist, they can be of great help in establishing family connections (particularly before census returns begin in 1841) and for researching the amount of personal property people owned.

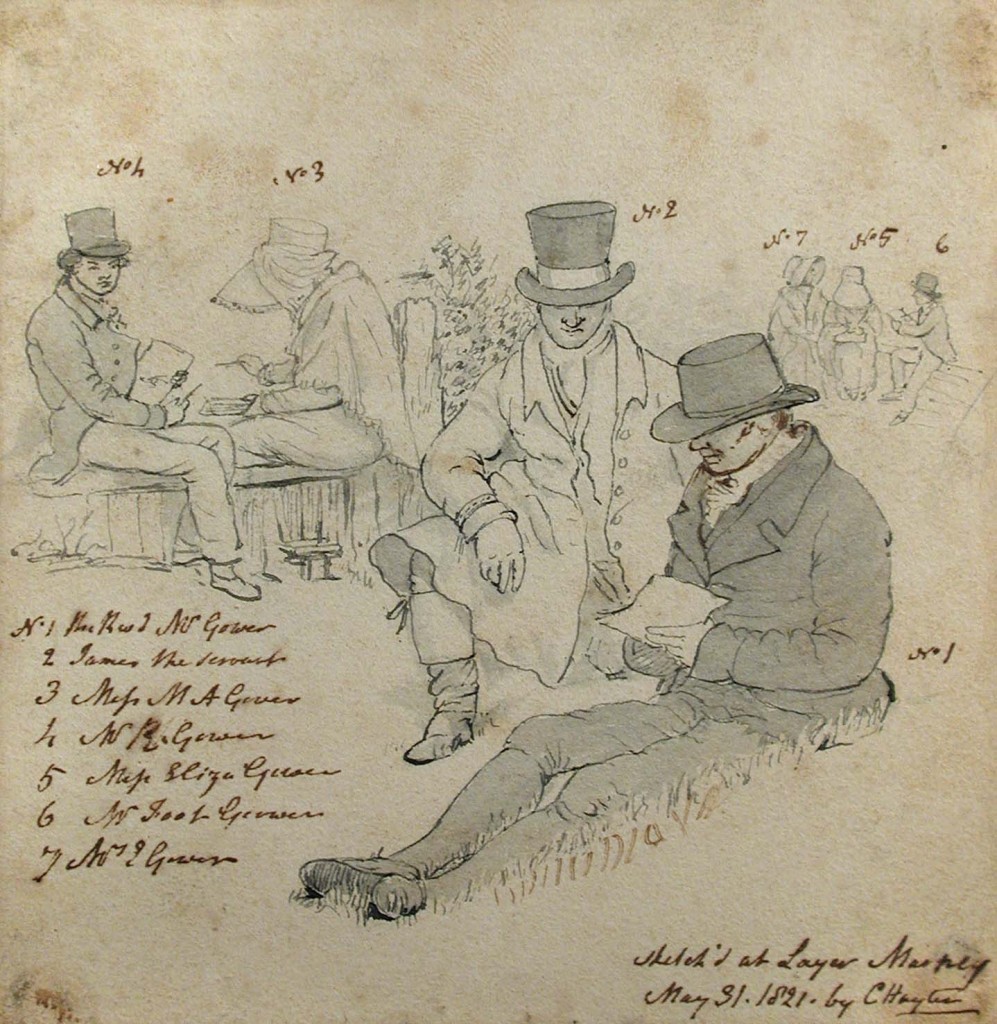

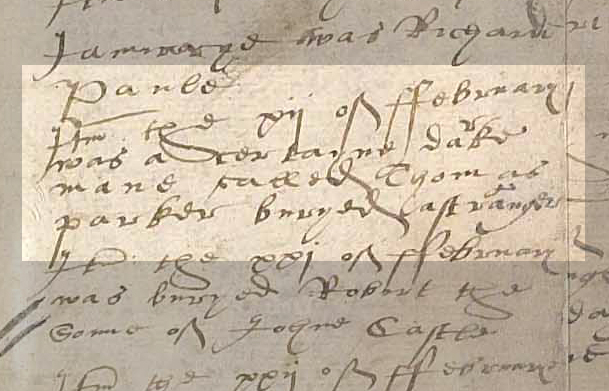

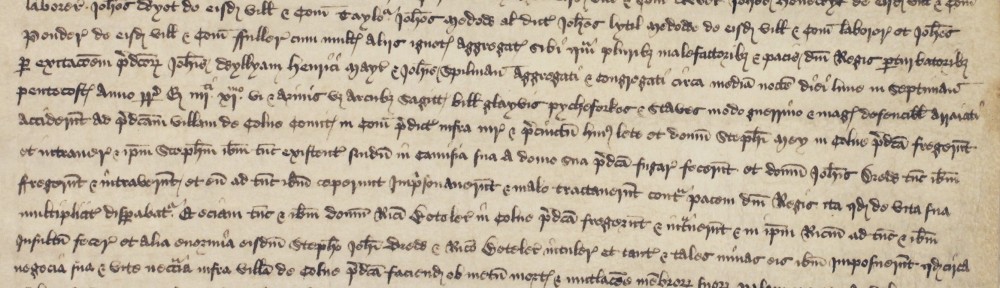

![It can be surprising to see what testators valued; in 1641 Elizabeth Fuller of Chigwell left her eldest son Henry my longe carte and dunge carte, my ponderinge crose my furnace, my mault quarne. We think the crose must be for religious contemplation and the quarne for grinding grain but it seems an odd mix of bequests. Her second son Robert received my best chest and my best brace [brass] pot which to modern eyes would seem to be the better bequest (D/AEW 21/71).](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/D-AEW-21-71-01-crop-1024x466.jpg)

It can be surprising to see what testators valued; in 1641 Elizabeth Fuller of Chigwell left her eldest son Henry ‘my longe carte and dunge carte, my ponderinge crose my furnace, my mault quarne’. We think the crose must be for religious contemplation and the quarne for grinding grain but it seems an odd mix of bequests. Her second son Robert received ‘my best chest and my best brace [brass] pot’ which to modern eyes might seem to be the better bequest (D/AEW 21/71).

This is a project we have been working on for many months, with our digitisers spending about 375 hours photographing the wills, our conservators spending about 44 hours conserving them, and our archivists spending about 752 hours checking all the images against their catalogue entries to get ready for the upload.

This upload will mean that digital images of all of our wills dating to c.1720 will be available on Essex Ancestors. We will now press on with working on the rest of the wills, which date from c.1720-1858, for upload in the next few months.To celebrate the upload, our archivists will be choosing some of their favourite wills to share on the blog over the next few days and weeks.

You can access Essex Ancestors from home as a subscriber, or for free in the Searchroom at the ERO in Chelmsford or at our Archive Access Points in Saffron Walden and Harlow. It will shortly be provided at Waltham Forest Archives. Opening hours vary, so please check before you visit.

Before you subscribe please check that the documents you need exist and have been digitised at http://seax.essexcc.gov.uk/

You can view a handy video guide to using Essex Ancestors here.

![It can be surprising to see what testators valued; in 1641 Elizabeth Fuller of Chigwell left her eldest son Henry my longe carte and dunge carte, my ponderinge crose my furnace, my mault quarne. We think the crose must be for religious contemplation and the quarne for grinding grain but it seems an odd mix of bequests. Her second son Robert received my best chest and my best brace [brass] pot which to modern eyes would seem to be the better bequest (D/AEW 21/71).](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/IMG_4446-1024x682.jpg)