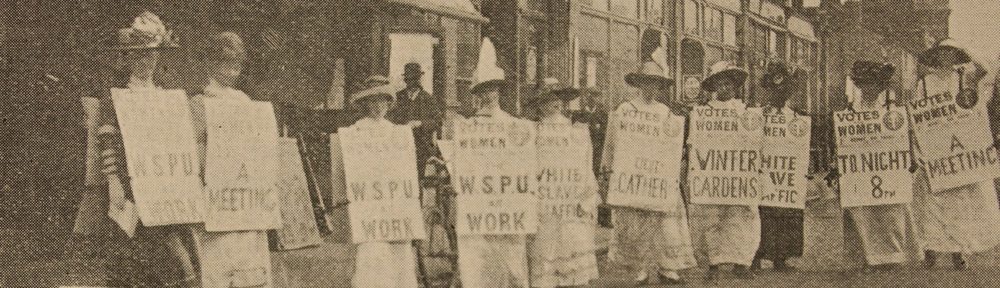

In the fifth post in our series looking at the history of Chelmsford High Street, Ashleigh Hudson looks at no. 38 High Street through the centuries. Find out more about the project here.

The site of 38 High Street is most often associated with the famous coaching inn, The Great Black Boy, which served Chelmsford residents and travellers alike for over three hundred years. The inn was demolished in 1857 and from the late 19th century, the site housed various retail establishments including fashion retailer Next who occupy the site today. A blue circular plaque commemorating the former site of the Black Boy currently sits just above the entrance of Next, ensuring that memory of the much revered inn lives on.

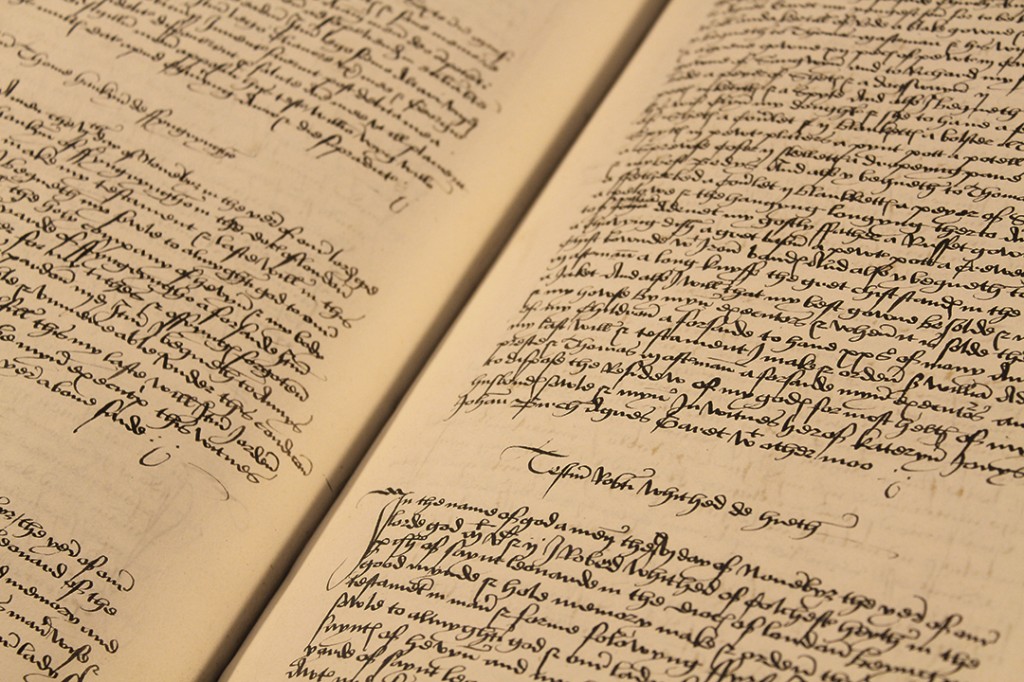

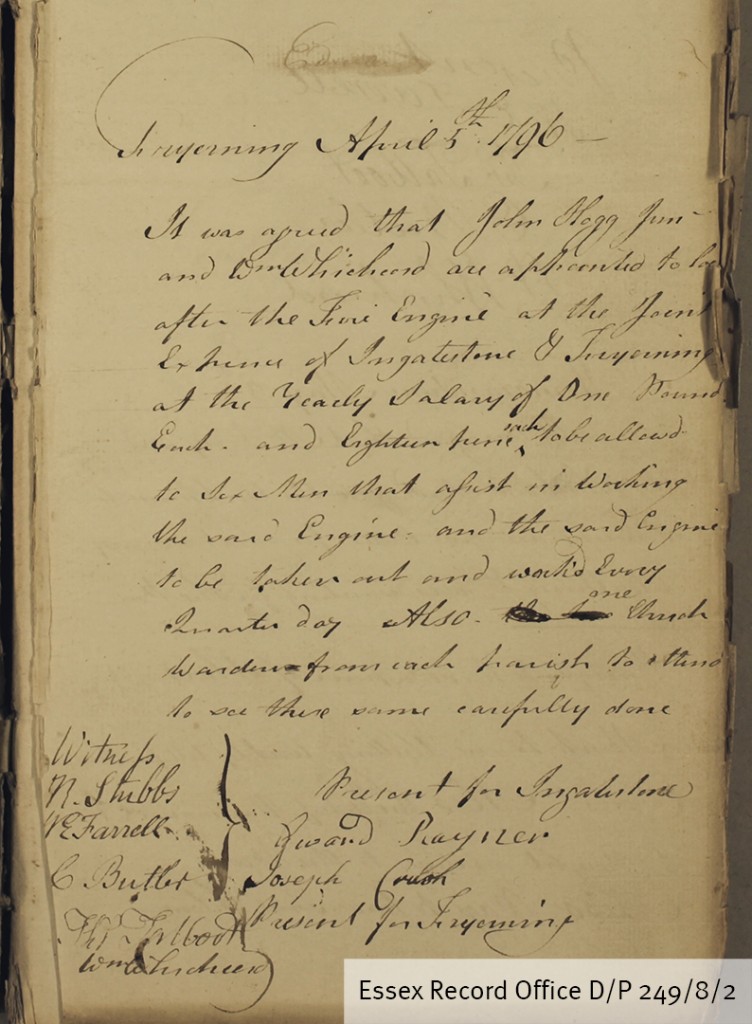

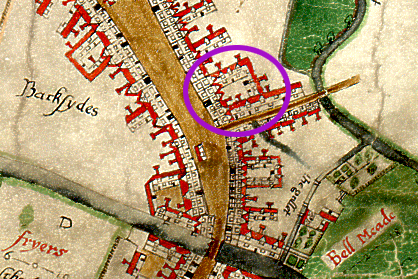

John Walker’s 1591 map of Chelmsford, with the Black Boy Inn highlighted on the junction between the High Street and what is now Springfield road

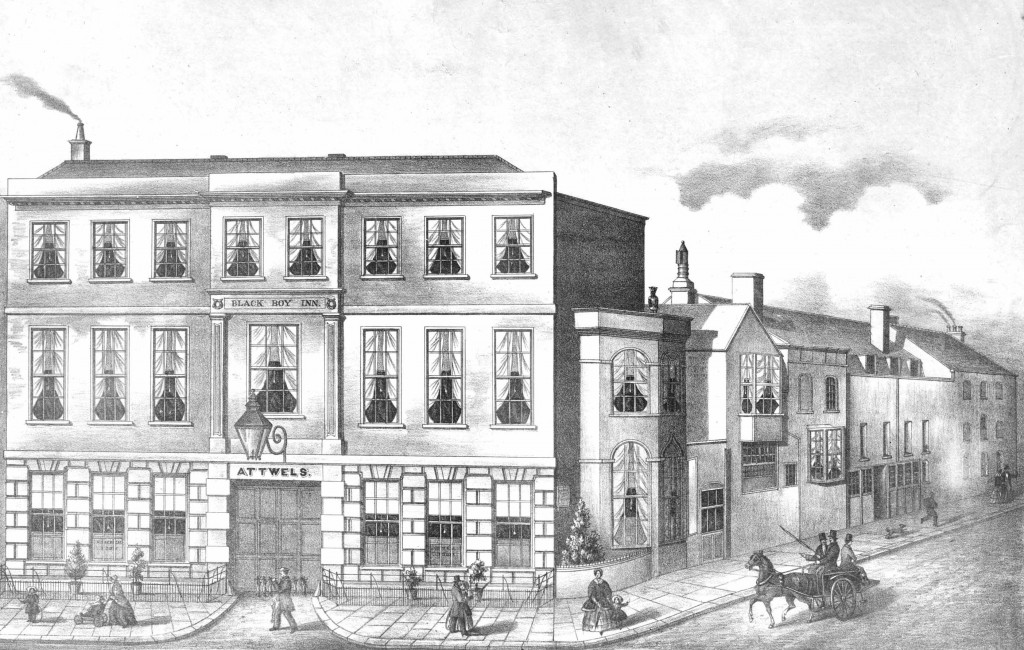

John Walker’s map of Chelmsford depicts a large, two storey property sitting on the site of 38 High Street. The property belonged to the widow Elizabeth Stafford and was known locally as the Crown or New Inn. By 1642 the inn was known as the Great Black Boy and was one of the most popular inns on the high street. Ideally situated on the Colchester to Harwich Road, the inn grew prosperous on the traffic passing through the town. During the 18th century, the original, timber building, as depicted on the Walker map, was pulled down and rebuilt.

During the 17th century, coaching inns were a fundamental part of the country’s transport system. The coaching inn provided travellers with space to eat, sleep, and drink, as well as stabling for horses. The Essex Record Office is fortunate to have a building plan of the Great Black Boy which reveals how coaching inns were typically constructed. A large gateway allowed coaches to pass through the property into the yard where the stables were located. Remarkably the gateway appears to sit on the same spot as in the Walker Map, despite the property having been rebuilt in the 18th century. The accommodation is situated relatively close to the yard, which perhaps made it difficult for guests to sleep undisturbed. A large inn such as the Black Boy could expect coaches coming and going throughout the day and night.

The Black Boy was also linked to the town’s mail service, accommodating the Post Office from 1673. The inn provided a mail coach service which passed through the town twice a day and contained a Post Office guard to ensure the coach safely reached its destination.

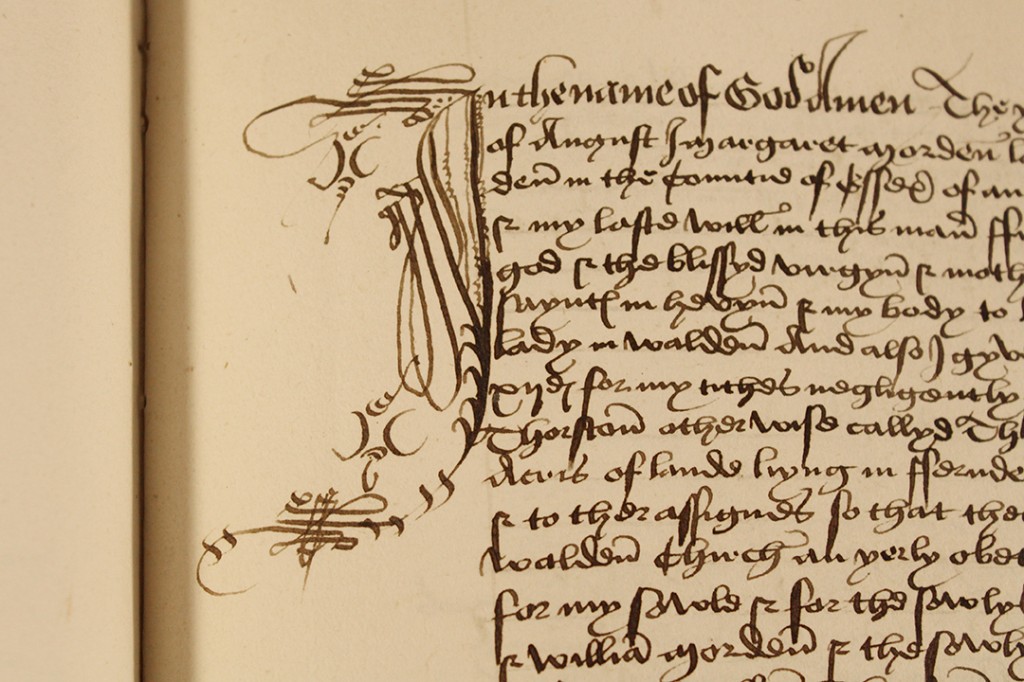

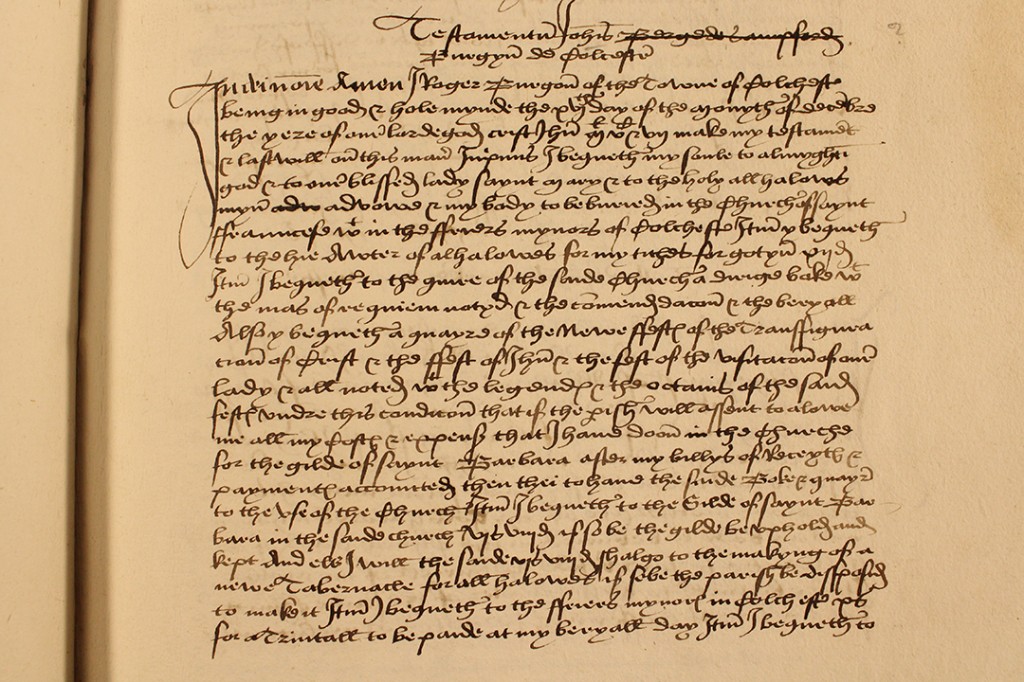

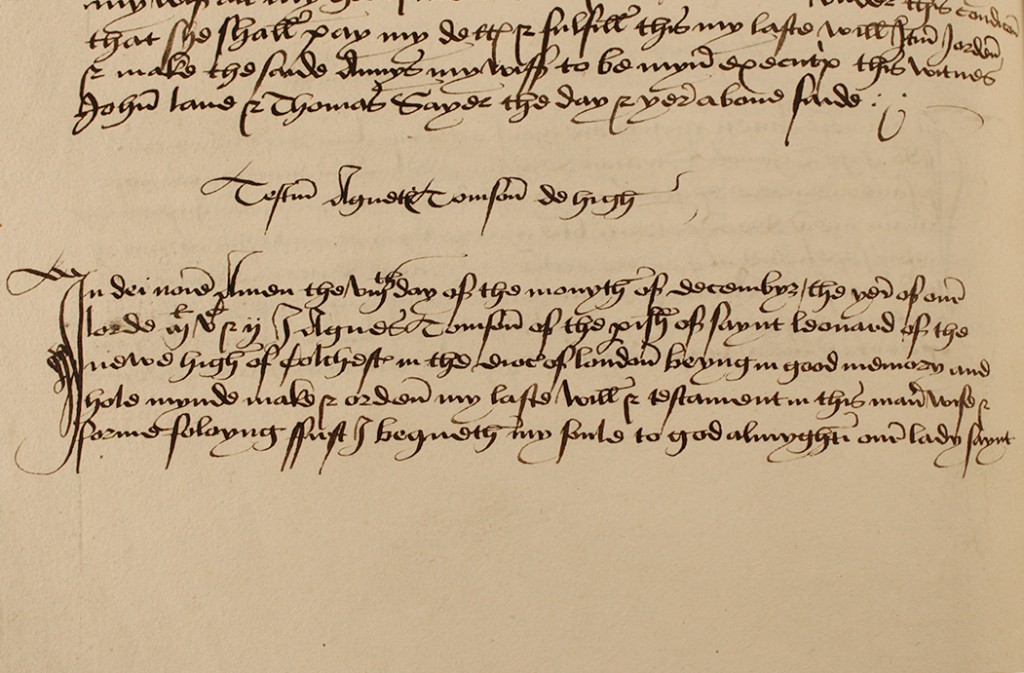

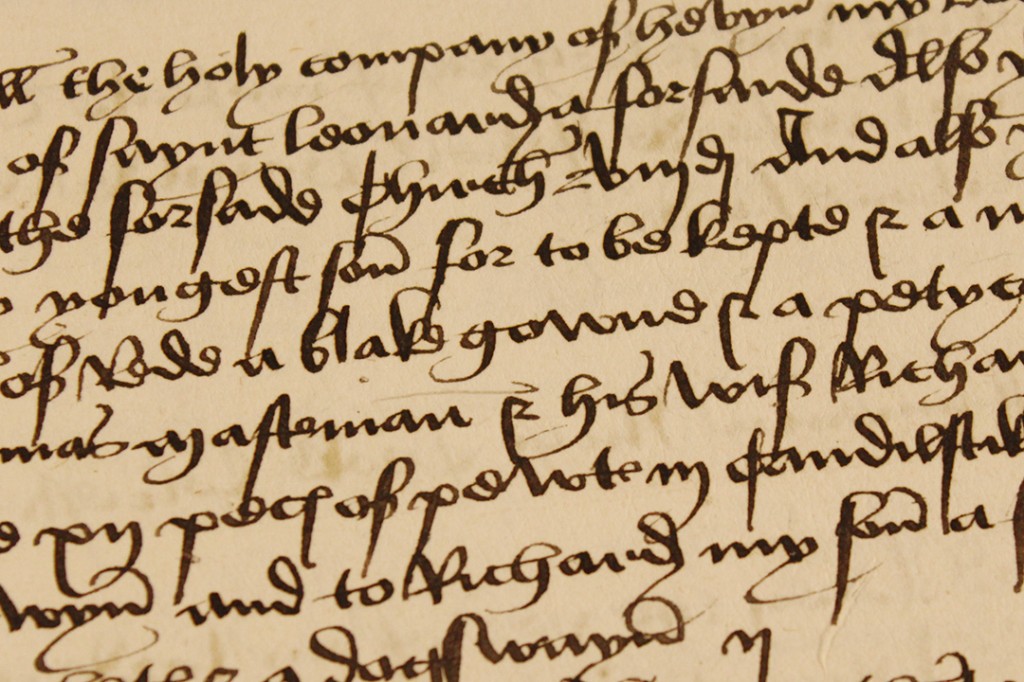

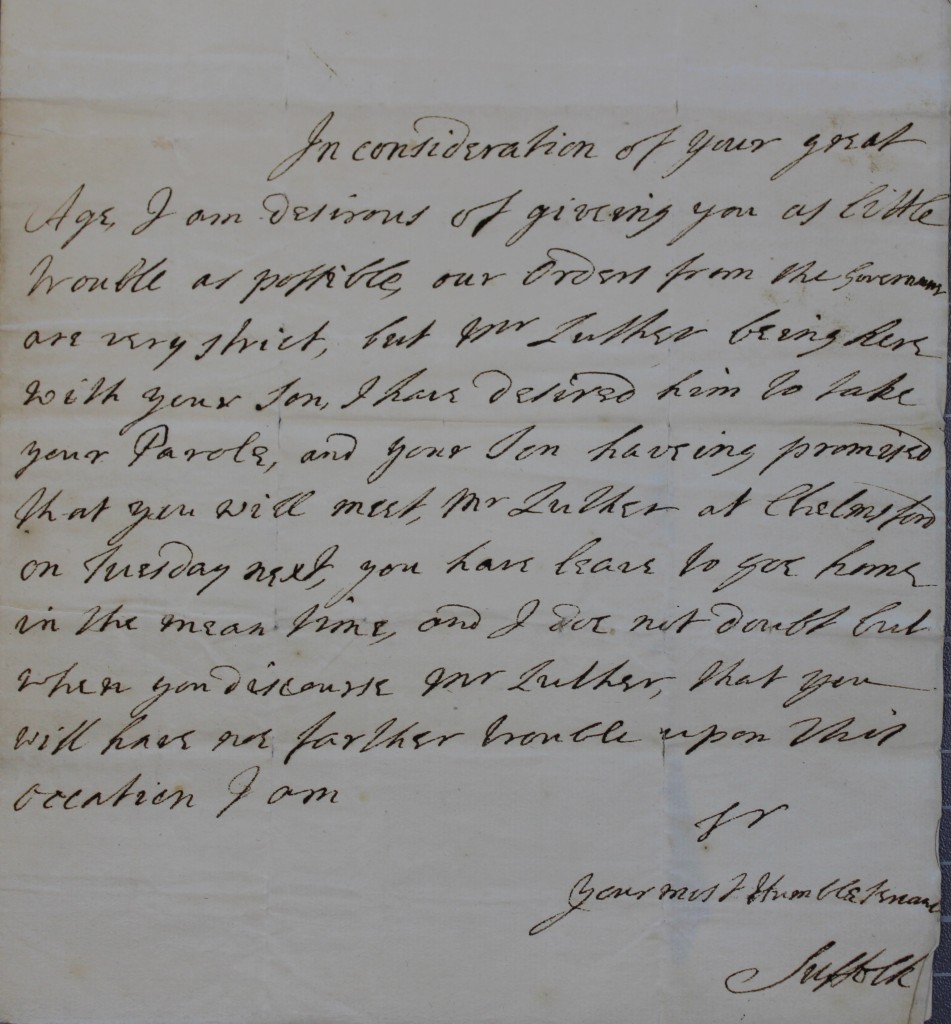

The Great Black Boy, by virtue of its great size, operated in various capacities. In the early 18th century for instance, the inn served as a detainment centre for residents deemed disloyal to the King. Several men were held at the inn under ‘suspicion of being disaffected to King George’. The Essex Record Office holds several letters written to Anthony Bramston during his incarceration at the inn.

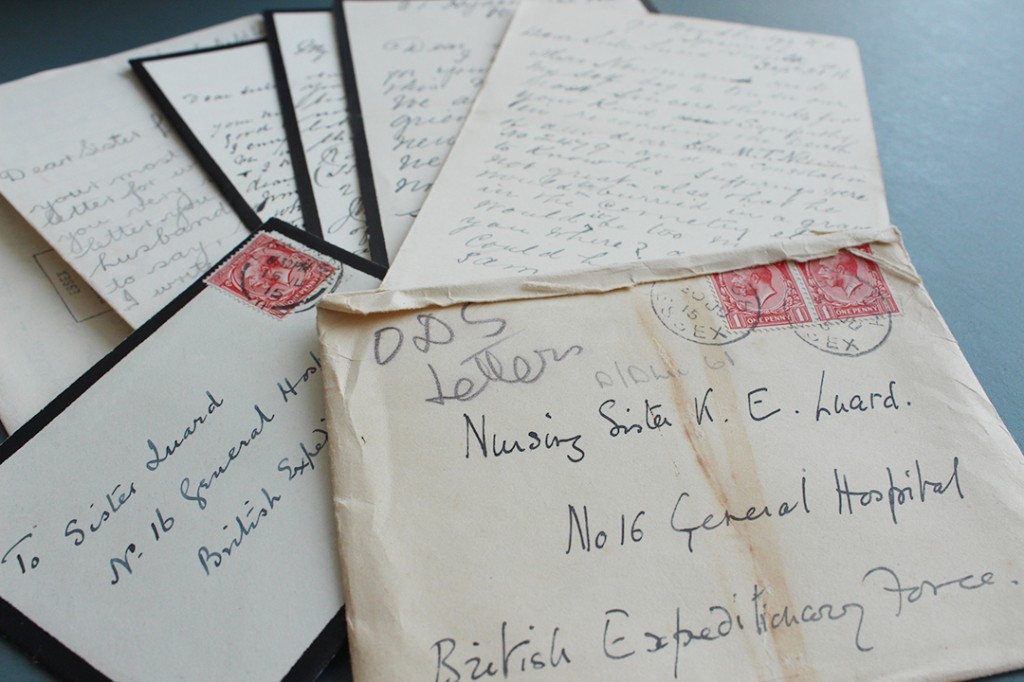

Letters to Anthony Bramston during his incarceration at the Black Boy Inn, Chelmsford, held on suspicion of disaffection to King George I. (D/Deb 70/1-4)

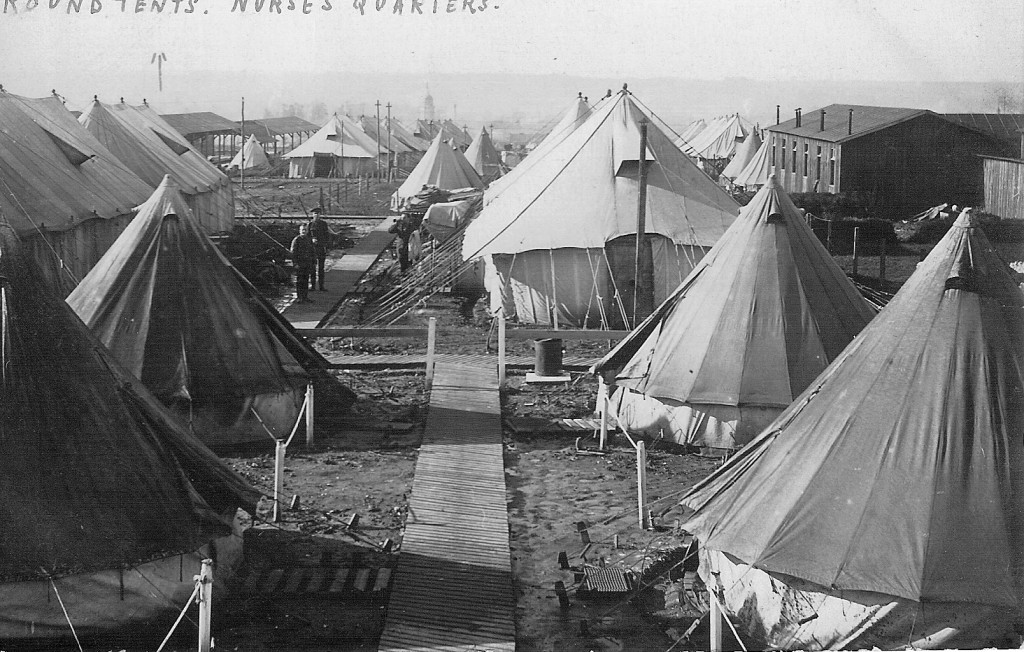

Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Great Black Boy was overwhelmed by an influx of military personnel, who were stationed in Chelmsford as hostilities between England and France escalated. The possibility of an attack via the Essex coastline must have seemed of secondary importance however to the town’s innkeepers who were kept extremely busy accommodating the spike in trade. The town was soon hosting more men than space could permit, and many soldiers resorted to sleeping in stables or barns.

From the late 18th century, the Great Black Boy served as an important social hub, providing a popular space for communal gatherings. Several clubs and societies, including the Chelmsford Tradesmen’s Club and the Chelmsford Pitt Club, met regularly at the inn. The Black Boy also hosted various assemblies and balls, although this practice declined somewhat after the construction of the Shire Hall in 1791. The inn also attracted many notable visitors in its day. In October 1832, the Chronicle reported that the Duke of Wellington changed horses at the Black Boy on his was to Sudbourn Hall for a shooting trip. A few years later, Charles Dickens reputedly stayed at the inn while working as a newspaper reporter. Looking out of his window at the Black Boy, Dickens famously concluded that Chelmsford was the ‘dullest and most stupid spot on the face of the earth’; to be fair apparently it was a rainy day.

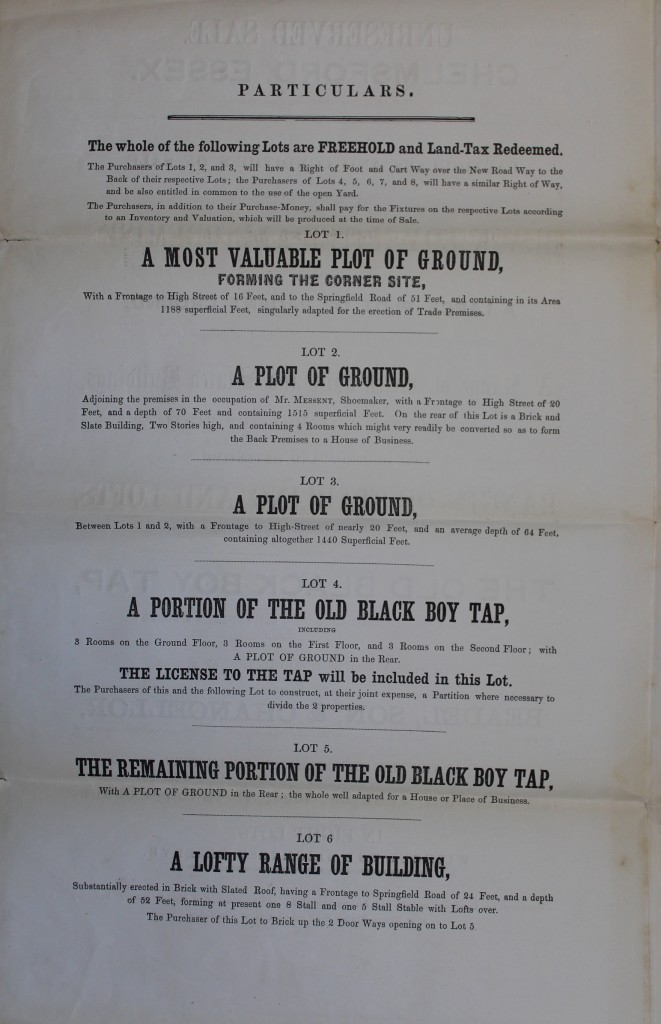

The arrival of the railway in Chelmsford in 1843 severely impeded the Black Boy’s trade by removing much of the passing traffic. By the mid-19th century the Black Boy was in decline with various outbuildings, stables and the yard progressively sold off. Between 1848 and 1851 the inn operated as a minor hotel. New owner John Amery was optimistic the business would turn around and committed the property to considerable alterations and improvements. Just ten years later, the Black Boy closed its doors for the last time. The inn was sold in 1857 and was later demolished leaving a gap on the high street which remained vacant for just over a decade.

Early Spalding photograph of Chelmsford High Street. On the far right it is possible to make out the gap left by the demolition of the Black Boy.

By 1868 the vacant space was ironically filled by Bernard’s Temperance Hotel. In the 19th century, Temperance advocates promoted alternatives to alcohol, which they viewed as a social evil.

Chelmsford High Street photographed from the south, revealing Barnard’s has now taken over the spot formerly occupied by the Black Boy inn.

The Hotel only survived on the site until the early 1920s, before it was once again put up for sale. The sale catalogue indicated excellent foresight in stating:

“…with its excellent depth could be easily converted to form one of the finest shops in the town, possessing as it does exceptional facilities for window front and display purposes…”

Shortly after, the site was filled by Boots the Chemists. Various alterations were made to the exterior of the property including the addition of large display windows. Just above the entrance, large lettering announces ‘Boots’.

View of Chelmsford High Street, taken from the south featuring Boots the Chemist on the former site of the Black Boy inn. The photograph captures Springfield corner prior to pedestrianisation. (SCN 3140).

The arrival of Boots in some ways indicated a break with the past and the beginning of a new era for the high street. The Black Boy had prospered because it catered for a specific need, that of travellers passing through the town on the London to Harwich Road. The arrival of the railway diminished the flow of traffic through the town and therefore the demand for accommodation. As the population increased, the demand for retail grew and the high street transitioned into a shopping destination.

The site is currently occupied by fashion retailer Next. The memory of the Black Boy inn is commemorated today by a blue circular plaque stationed just above the entrance to Next.

If you would like to find out more about this famous posting house, try searching for ‘Black Boy Inn’ on Seax. Alternatively, see Hilda Grieves’s detailed history of Chelmsford The Sleepers and The Shadows which is available in the ERO Searchroom.