Note: Some of the records discussed in this blog post contain language that you may find offensive or distressing.

As the destination for the Empire Windrush, which arrived at the Port of Tilbury on 21 June 1948, Essex has a prominent place in recent Black British history. However, people from African and Caribbean backgrounds have been part of the history of this county for centuries, and as Essex becomes an increasingly diverse place today, new histories continue to be made.

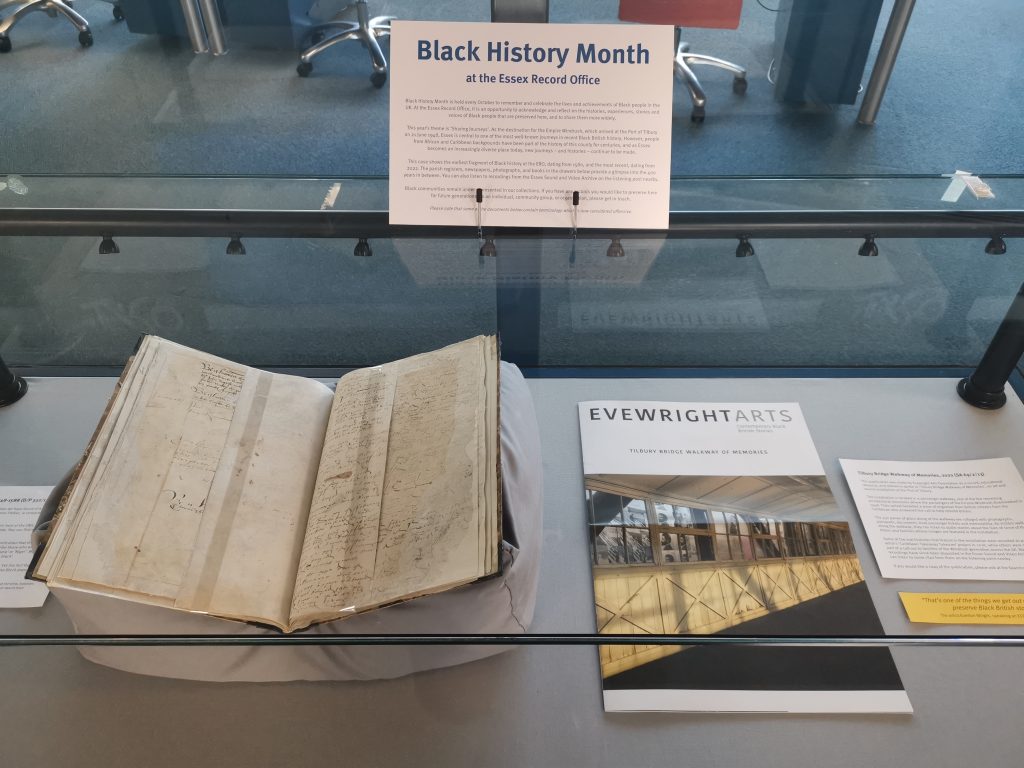

Black History Month is held every October to celebrate the lives and achievements of Black people in the UK. At the ERO, it is an opportunity to reflect on the histories of Black people that are preserved here, and to share their stories and voices more widely.

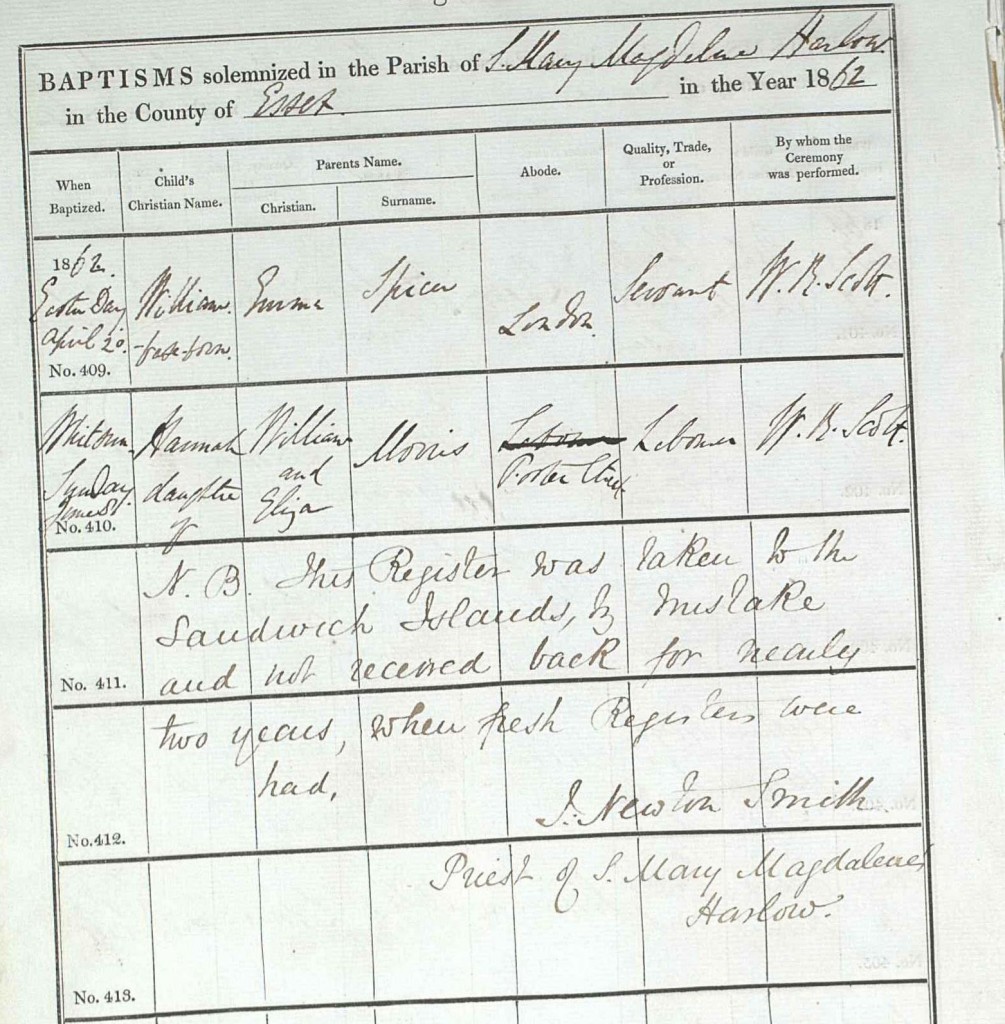

The display cabinet in our Searchroom is currently home to the earliest fragment of Black history at the ERO, dating from 1580, and the most recent, dating from 2022. There are also parish registers, newspapers, photographs, books and sound recordings to look at and listen to in the drawers below and on the listening post nearby.

In Part 1 of this blog post, we’ll take a closer look at some of the parish registers on display, which date from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. In Part 2, we’ll explore much more recent recordings from the Essex Sound and Video Archive. In comparison to the parish registers, which often record Black people as the ‘other’, many of the recordings preserved in the ESVA record the experiences of Black people in their own words.

Parish registers

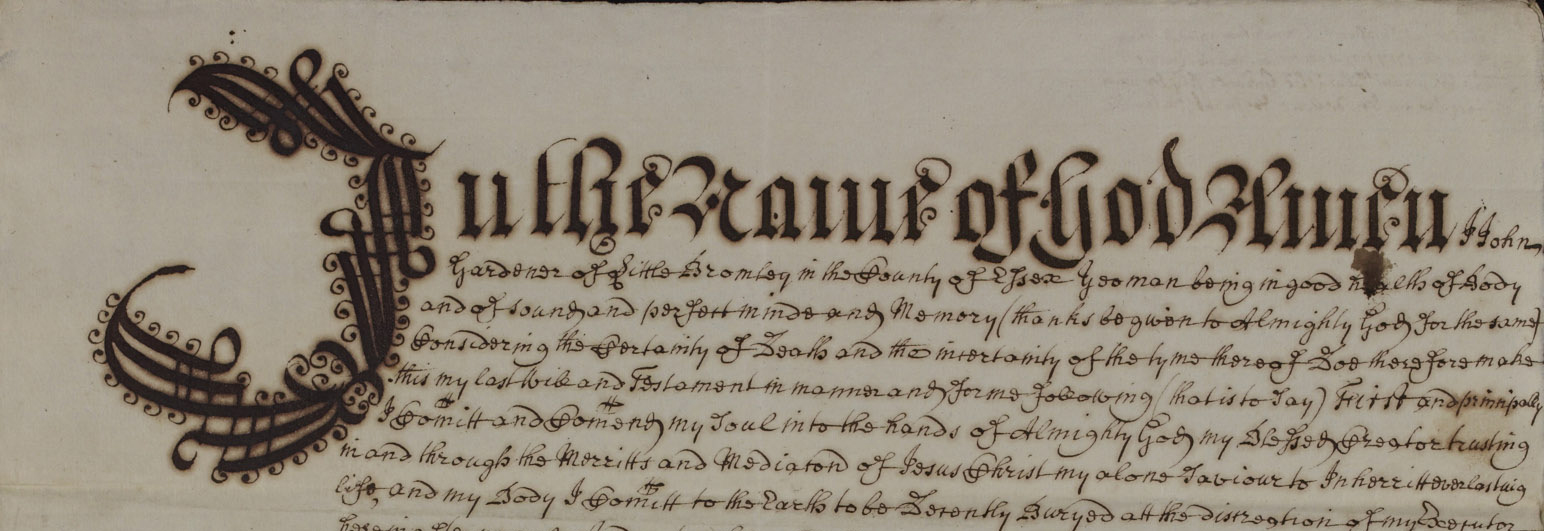

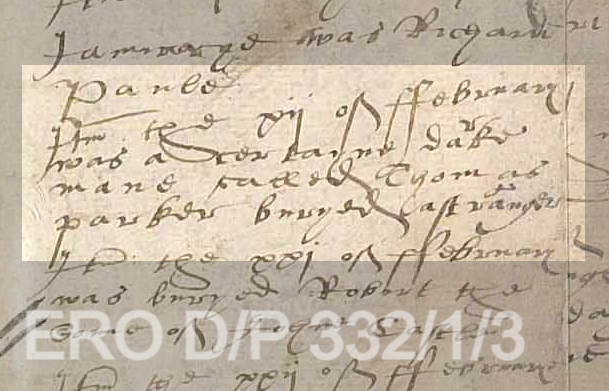

The Rayleigh parish register displayed at the top of the case contains the earliest mention we have found of a Black individual in our collections; the burial record of Thomas Parker, ‘a certayne darke mane’ in Rayleigh in 1579/1580*. While the use of the word ‘dark’ is not always an indication that the person was of African descent or origin, it was often used to describe those who were.

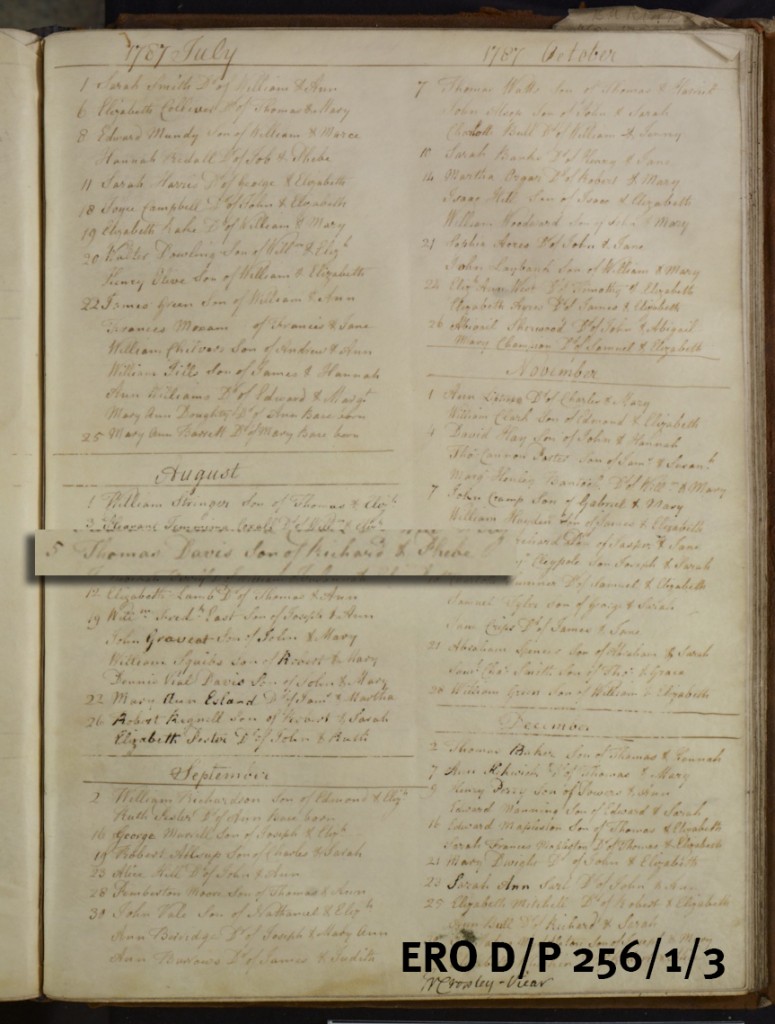

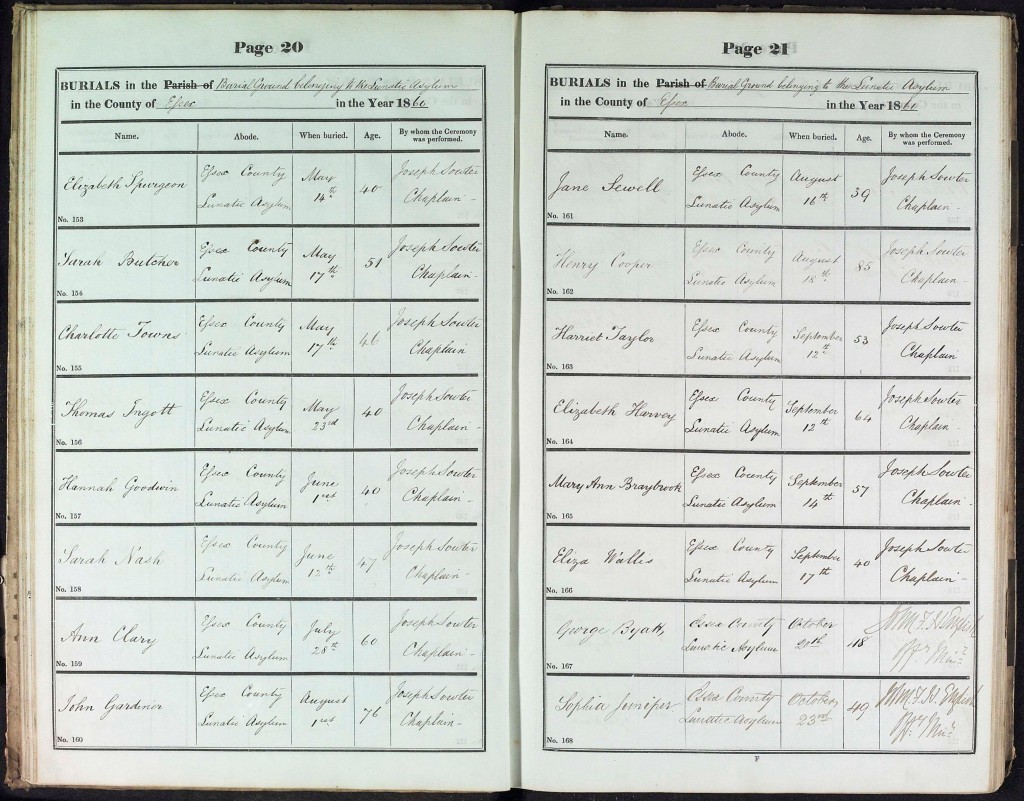

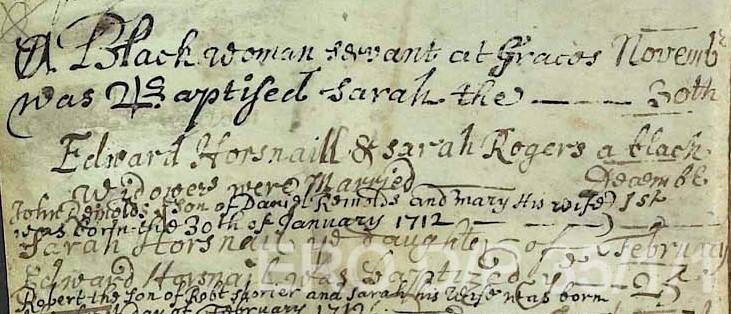

More commonly, the church ministers or wardens who kept the parish registers described people of African or Caribbean descent as ‘Negro’ or ‘a Black’. These terms are obviously outdated and offensive today. Yet, to the present-day researcher, these references highlight the existence of Black people in Essex during this period; in most cases, the entries in the registers are the only record of their lives that has survived. By giving us their names, and the date and place they were baptised, married, or buried (and sometimes, if they were a servant, the name of their employer), they provide a glimpse into who they were, and allows us to understand more about the Black population in Essex as a whole.

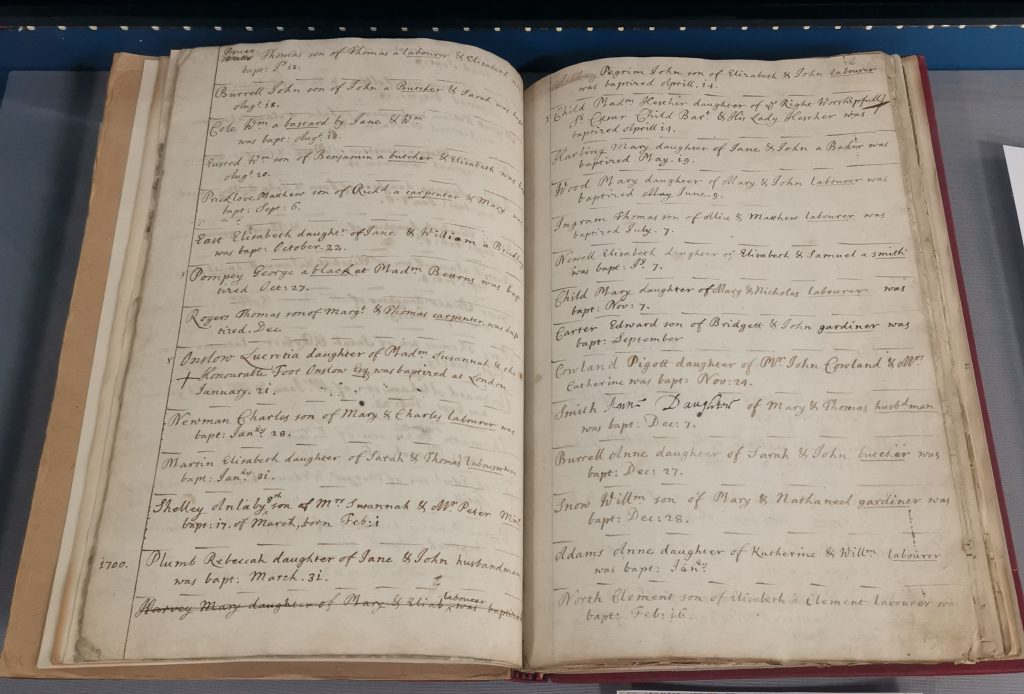

In some cases, where the same name appears in more than one parish register or document, we can build up a more detailed picture. This register from the parish of St Mary the Virgin, Woodford, records the baptism of George Pompey, ‘a black at Madm Bettons’, in October 1699.

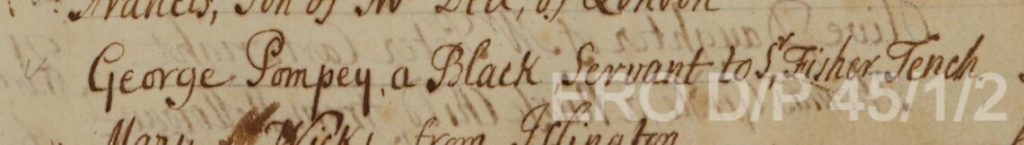

Another reference to ‘George Pompey a Black, servant to Sir Fisher Tench’ can be found in the parish register for Leyton, which records his burial on 3 September 1735. Fisher Tench was a city merchant who was deeply involved in the transatlantic slave trade; as well as owning a plantation in Virginia, he was also sub-Governor of the Royal Africa Company and Director of the South Sea Company.

The inscription on George’s headstone noted that he died aged 32, after working for the Tench family for over twenty years – probably at the Great House in Leyton, which they built in the early 1700s. It is possible that George’s age was mistaken, and that this is the same George that was baptised in Woodford thirty-six years earlier. It is not impossible, however, that there were two people called George Pompey in the area at the time; during this period it was common for enslaved people to be given classical names, like Pompey, when they were baptised.

As well as baptisms and burials, the registers also recorded the marriages that took place in each parish, including inter-racial marriages. This parish register from Little Baddow shows that Sarah, ‘a Black woman servant at Graces’ was baptised on 30 November 1712, and married Edward Horsnail the next day, on 1 December. Their daughter, also called Sarah, was baptised on 25 February the following year (it wasn’t unusual at this time for children to be born only a few months after a marriage took place).

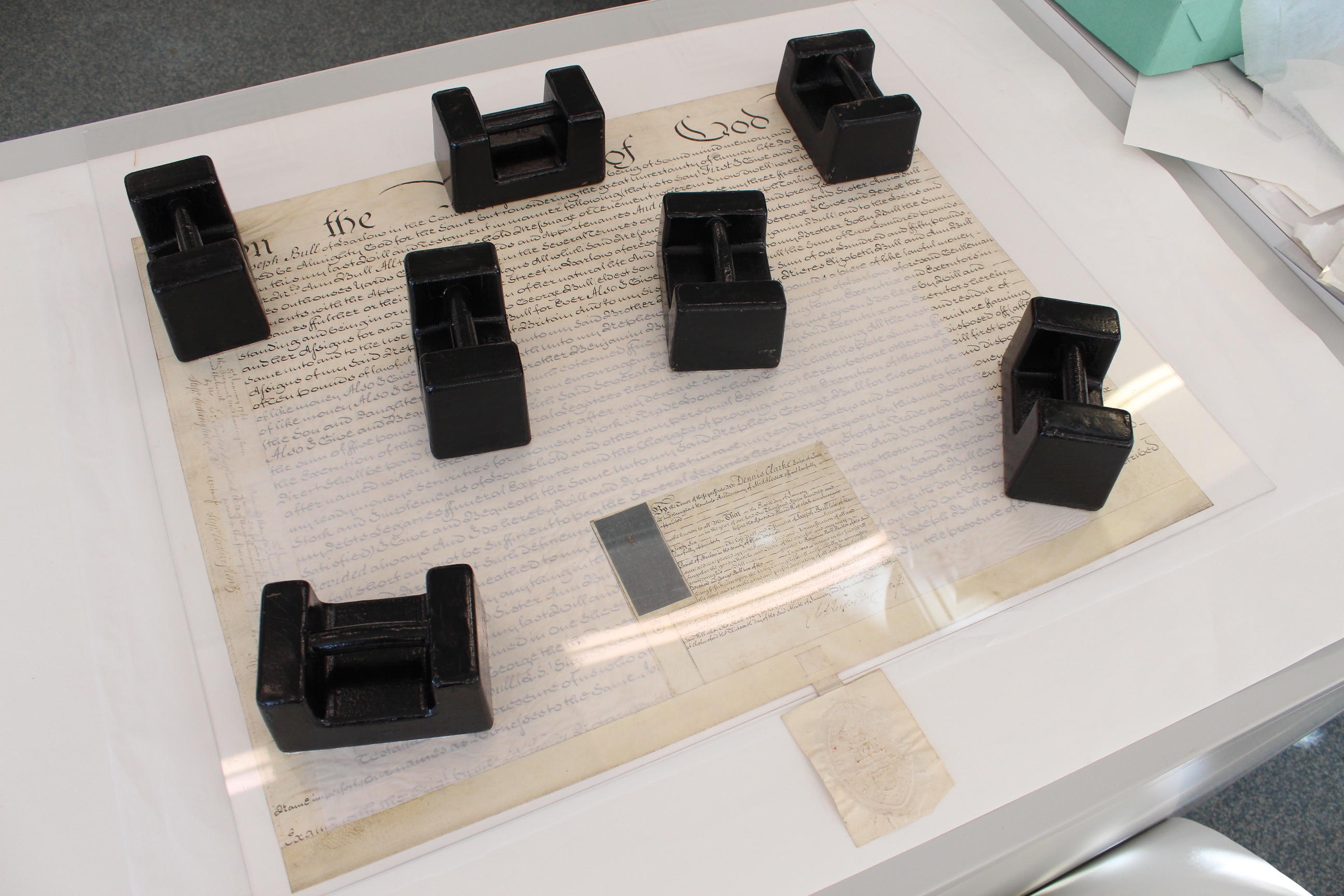

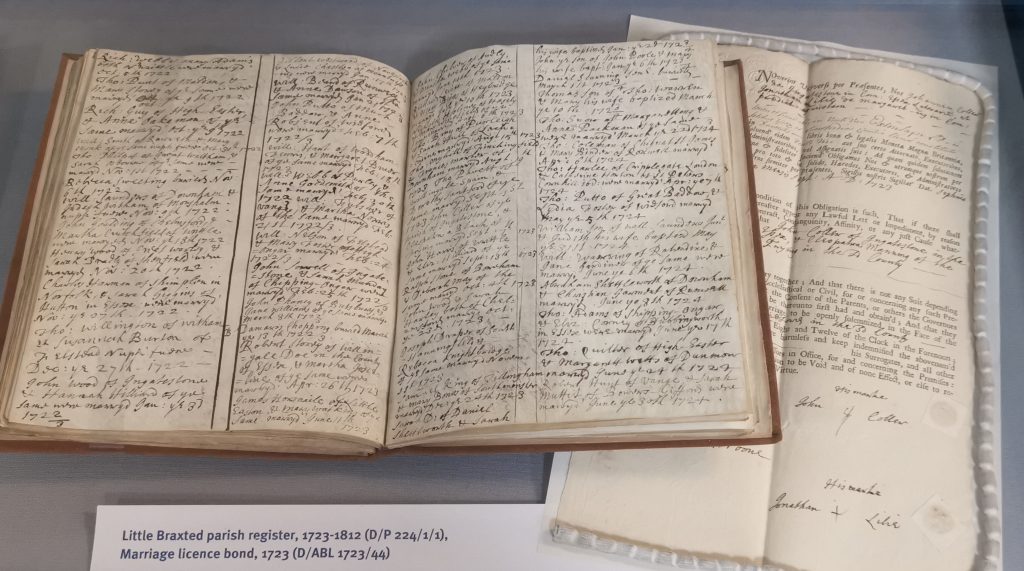

Ten years later, the rector of Little Braxted recorded the marriage of Cleopatra Manning ‘a black, of Fryerning’ to John Coller ‘of ye parish of Ingatestone’. Interestingly, the marriage bond beside the register below shows that John applied to marry Cleopatra by licence, which meant that banns did not have to be read out in church.

Parish registers like these record an increasing number of Black people living and working in Essex from the seventeenth century.

This increase was inextricably linked to the rise of the transatlantic slave trade. Several prominent families in Essex owned plantations in the Caribbean and benefited financially from the labour of enslaved people**. While some Black people arrived in Essex as seamen, labourers, or artisans, either from London or abroad, others were brought to the county to work as servants.

The legal status of this group of people was ambiguous. While some rulings stated that enslaved people became free on arrival on British soil, or after being baptised, others suggested that they could continue to be treated as property. In 1772, the judgement in the Somerset v. Stewart case stated that ‘no master’ was allowed ‘to take a slave by force to be sold abroad’. Although some people understood this to mean the abolition of slavery in England, the practice continued, and it was not until 1833 that it was formally outlawed.

Very few people are identified in the parish registers as ‘slaves’; more commonly, people are listed as being ‘of’ or ‘belonging to’ their masters – like Rebecca Magarth, who was recorded in the Broomfield parish register in January 1736/7 as ‘belonging to Edward Kelsall’ (D/P 248/1/1). A much greater number are listed as servants. The experiences of these people would have varied enormously, both between individuals and over the time period. It is likely, however, that many would not have been free to leave their employers or been paid for their labour.

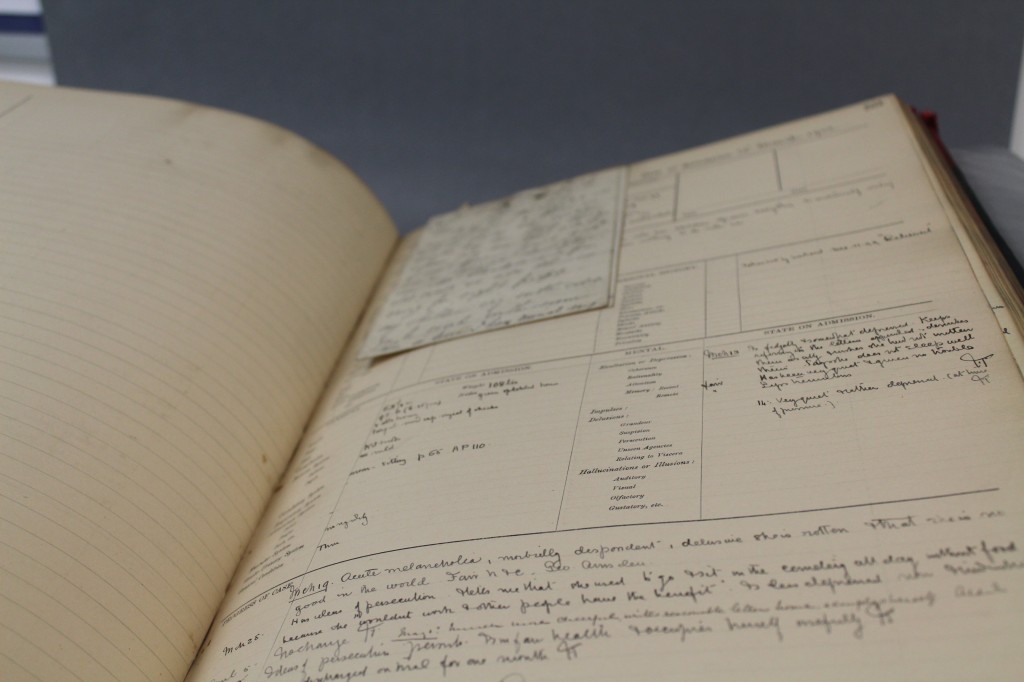

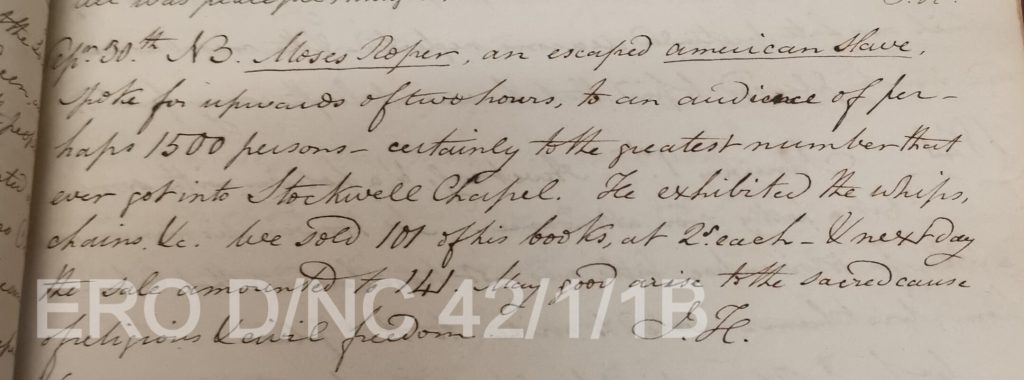

Beyond the memoirs of people like Mary Prince, who had been enslaved on Bermuda and Antigua before being brought to England as a servant in 1828, very little has survived that can tell us about these experiences. However, other documents from the archive do record examples of of agency and resistance. Alongside the activities of white abolitionists, like John Farmer, Thomas Fowell Buxton and Anne Knight, the records show that hundreds of people in Essex attended lectures given by formerly enslaved people about their experiences, usually in America. In the 1840s, the author and activist Moses Roper spoke in more than a dozen places across the county, including Stockwell Congregational Chapel in Colchester. A volume from the church records suggests the audience of 1,500 was ‘the greatest number’ the chapel had ever seen. Seven years later, the same volume details a lecture at the Friends’ Meeting House by Frederick Douglass, a leader of the abolitionist and civil rights movement in the USA .

Some traces also remain of those mentioned in the parish registers outside the archive. While George Pompey’s headstone in Leyton no longer survives, other memorials commemorating the lives of Black people during this period can still be seen today. In 2018, Elsa James’s Forgotten Black Essex project highlighted the story of Hester Woodley, who died in Little Parndon in 1767, aged 62. Hester and her adult daughter Jane were brought to Essex from a plantation on Montserrat in around 1740, to work for Bridget Woodley. When she died, the Woodley family erected a memorial in St Mary’s Church ‘as a grateful remembrance of her faithfully discharging her duty with the utmost attention and integrity’. Although it was intended as a tribute, the inscription makes it clear that Hester was considered the property of the family, ‘to whom she belonged during her life’.

Another memorial in St Andrew’s Church, Heybridge, remembers Eleanor Incleden, who died in 1823 aged 45 (a record of her burial can be found in the Heybridge parish register, D/P 44/1/6). Eleanor had worked at Heybridge Hall for Oliver Hering, Deputy Lieutenant of Essex, and his wife Mary, who erected the memorial: a ‘small tribute of respect and gratitude to her exemplary worth, and the merits and sorrows of her son’. It also notes that Eleanor was Jamaican, so it is possible that she was brought to Essex from Paul Island, the Hering’s sugar estate on Jamaica.

In 2022, the gravestone of Joseph Freeman in the non-conformist cemetery on New London Road, Chelmsford, was given Grade II listed status. Freeman had been born into slavery in Louisiana around 1830, but managed to liberate himself at the start of the American Civil War. He then moved to Essex, settled down with a local woman in Moulsham, and worked at the London Road Iron Works until his death in 1875.

These are a small sample of the records that include references to Black people from this period. We keep a running list of all the references to people from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds we find in the parish registers. If you would like to see the full list, please email ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk. You can also find out more about some of these records in this earlier blog post.

For more information, see:

- David Killingray – ”All conditions of life and labour’: the presence of Black people in Essex before 1950′, Essex Archaeology and History Volume 35 (2004)

- S.I. Martin – ‘Tilbury Past and Present’, Tilbury Bridge Walkway of Memories legacy publication (2022)

Thanks also to Evewright Arts Foundation and Elsa James for shedding light on Black histories in Essex, and recording new histories to preserve for future generations.

*Thomas was buried on 12 February in the year that we would call 1580; at the time, however, New Year was marked on 25 March rather than 1 January, so contemporaries would have thought of it as still being 1579.

**Examples include the Neave family of Dagnam Park, the Conyers of Copped Hall, and the Palmers of Nazeing Hall, who were all awarded compensation under the Slave Compensation Act of 1837. Records relating to their involvement in plantations, including lists of enslaved people who worked on them, are held at the ERO. For a detailed list of these, email ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk.