Is there something in our collection that you would love to investigate, but you aren’t able to visit us yourself? Or perhaps a document that contains vital information, but it’s just too tricky to decipher? Whether you are researching the history of your family, your house, or a vintage or classic vehicle, our Search Service might be able to help you.

One of the most frequent search requests we receive is to dig out information from the tens of thousands of wills in our collection. These date from around 1400 up to 1858, and contain all sorts of juicy nuggets of historical information.

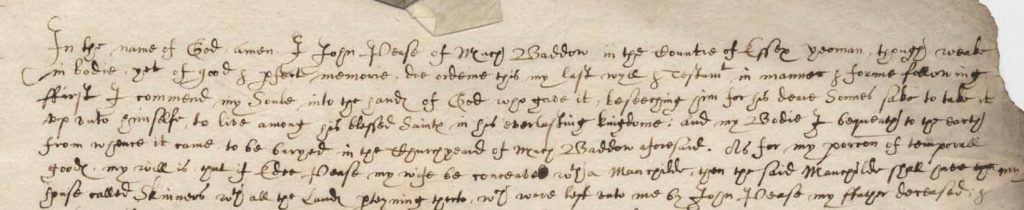

One such will that our Search Service was recently asked to transcribe was left in 1615 by John Pease, who was a yeoman and lived in Great Baddow (D/ABW 30/235). Getting to look at a document in this amount of detail and delve into the lives of people long gone is always a treat, despite the trickiness of the handwriting.

The beginning of John Pease’s will, made on 11th January 1615. Just three days later his burial is recorded in the local churchyard.

Wills can be fabulously interesting documents and if you are particularly lucky you will find out the names of family and friends and details of property and this will is no exception. As is usual for a will of this period John Pease ensures that there is no doubt that while he is ‘weak in bodie’ he is ‘yet of good & p[er]fect memorie’. If there was any doubt as to his mental capacity then, just as now, his will would be invalid. He bequeaths his soul to God and his ‘Bodie I bequeath to the earth from where it came to be buryed in the Churchyard of Much [Great] Baddow’.

Interestingly there must have been some doubt in his mind as to if his wife Edee was pregnant or not for he goes on to describe what was to happen if, having three daughters already, his wife ‘be conceaved w[i]th a man child’ or ‘be conceaved with a woman child’. If it were a boy then he was to get certain land and property and if it were a girl then their inheritance was taken in to account along with his daughters Mary, Margaret & Edee. Reading between the lines you get the impression he was hoping for a boy!

John thought he was leaving his wife Edee expecting a child. He made various provisions in the case of the birth of a ‘man child’ and different provisions for a ‘woman child’

And what of John? Well his will is dated 11 January 1615. On examination of the relevant parish register for Great Baddow St Mary there is an entry made on the 14 January 1615 noting his burial (D/P 65/1/1, image 202) – he didn’t last long when he realised he had better make his will. Checking the baptism entries for Great Baddow for the months following his death there does not appear to be a record of a baptism of another Pease child so it seems that after all there was nothing to worry about.

So Edee, John’s wife, was now a widow and a quick check of the marriages for the few years after 1615 doesn’t show her getting re-married. However, there is an entry on August 11 1617 (D/P 65/1/1, image 123) for the marriage of Thomas Turner[?] and Margaret Pease. Could this possibly be John’s second daughter?

All documents tend to answer some questions and ask several more, which is one of the things that can make historical research such an addictive thing to do. If there’s a document you would like to see at ERO but you can’t visit, or you need some help understanding it, our Search Service is here to help – just get in touch on ero.searchroom@essex.gov.uk or 033301 32500 for further details and prices.

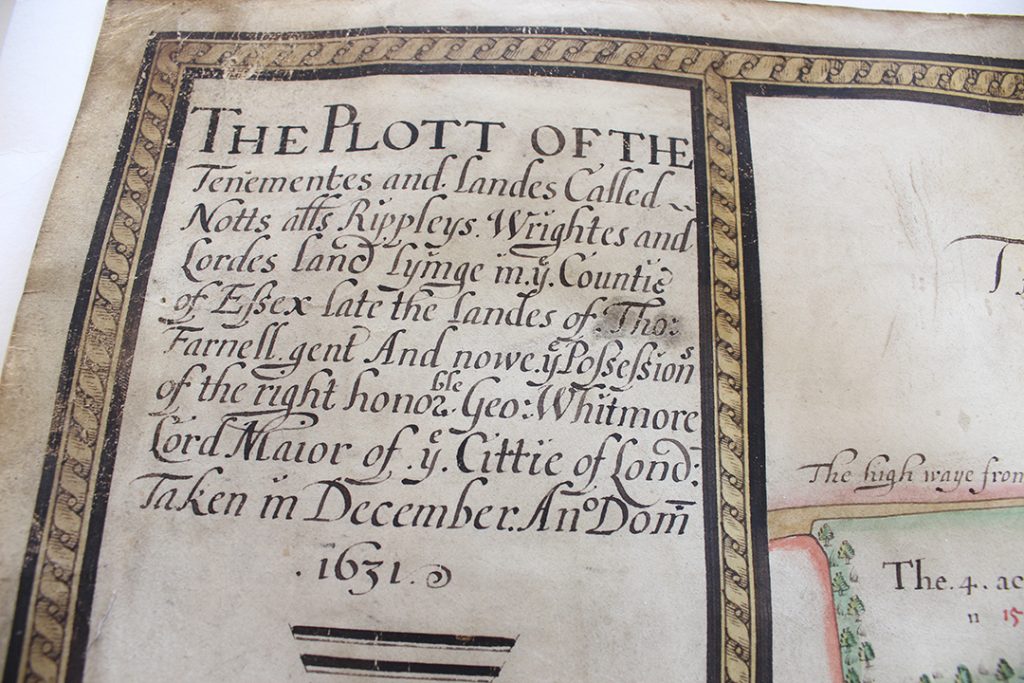

![It can be surprising to see what testators valued; in 1641 Elizabeth Fuller of Chigwell left her eldest son Henry my longe carte and dunge carte, my ponderinge crose my furnace, my mault quarne. We think the crose must be for religious contemplation and the quarne for grinding grain but it seems an odd mix of bequests. Her second son Robert received my best chest and my best brace [brass] pot which to modern eyes would seem to be the better bequest (D/AEW 21/71).](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/D-AEW-21-71-01-crop-1024x466.jpg)

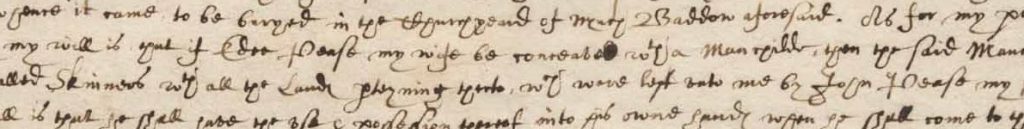

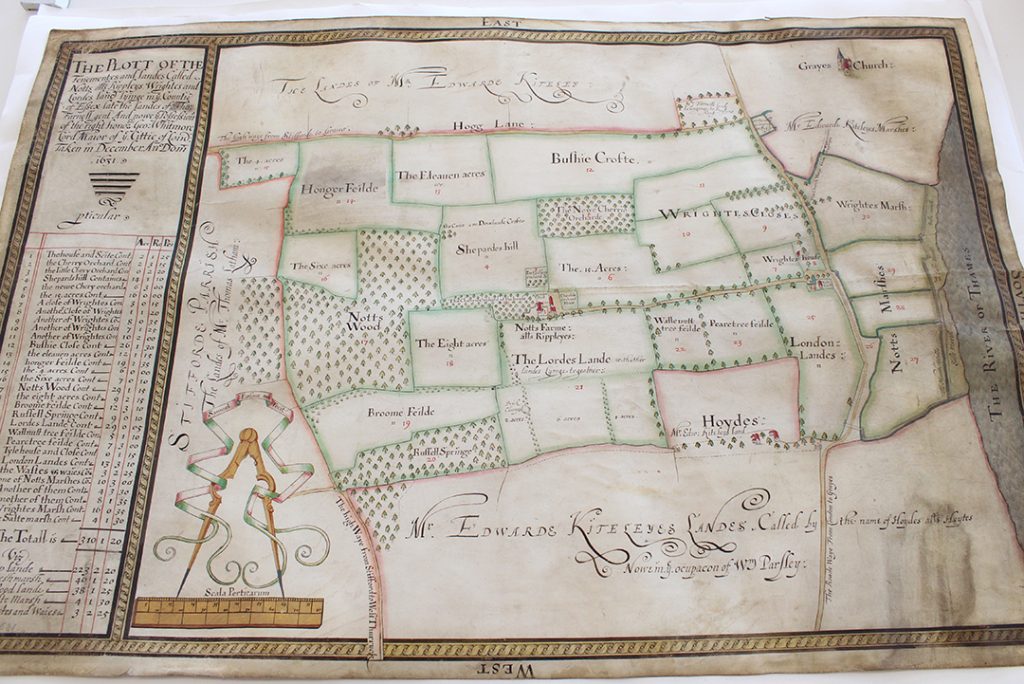

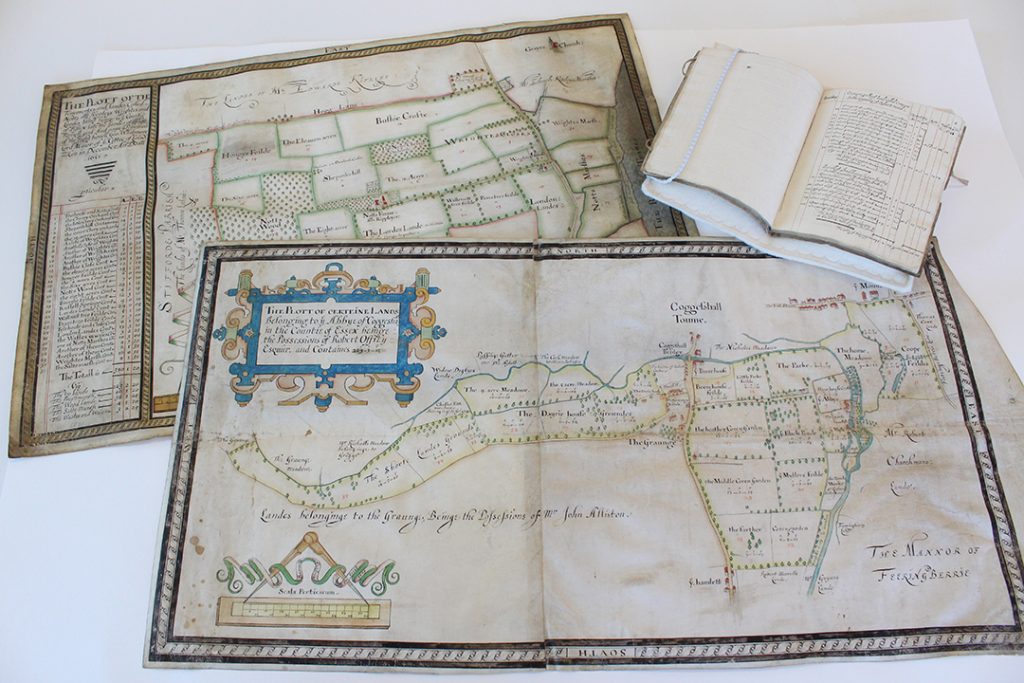

![It can be surprising to see what testators valued; in 1641 Elizabeth Fuller of Chigwell left her eldest son Henry my longe carte and dunge carte, my ponderinge crose my furnace, my mault quarne. We think the crose must be for religious contemplation and the quarne for grinding grain but it seems an odd mix of bequests. Her second son Robert received my best chest and my best brace [brass] pot which to modern eyes would seem to be the better bequest (D/AEW 21/71).](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/IMG_4446-1024x682.jpg)