Chris Lambert, Archivist

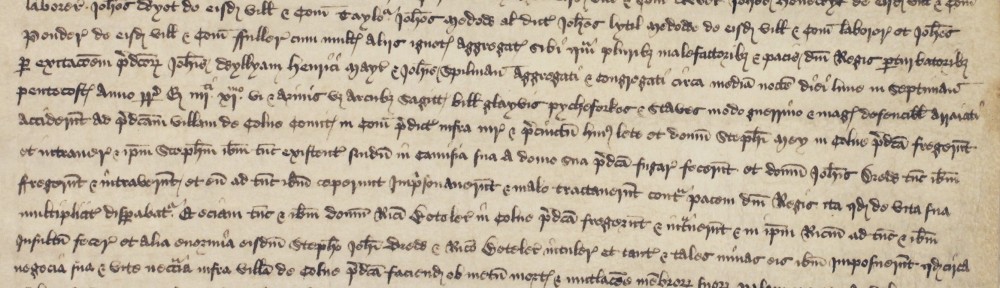

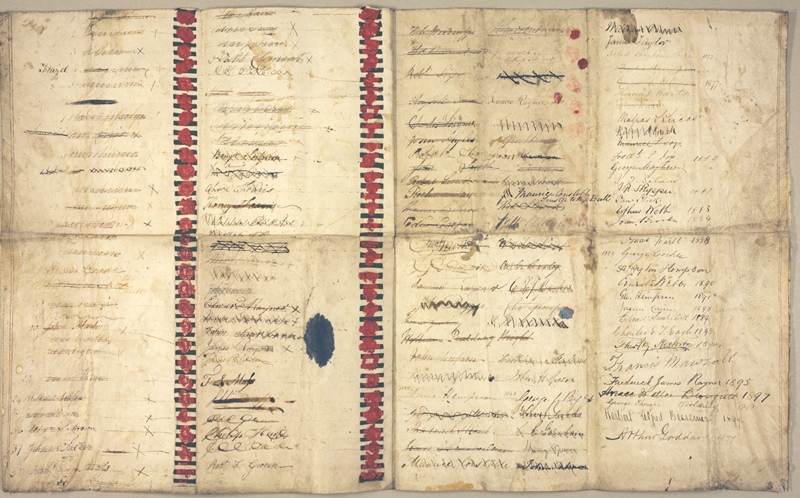

D/DSe 13

Our document this month is actually 3 documents, chosen to illustrate how a national political and economic crisis works at a personal level – or at least, how it did in Britain in 1816.

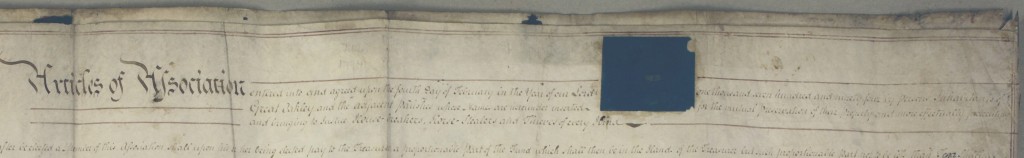

They all come from the correspondence of James Brogden, long-serving MP for Launceston in Cornwall. He actually lived in Clapham, but his papers came to Essex through his sister Susannah, who married into a local family.

1816 should have been a year of relaxation, with the long years of war against France finally over. Unfortunately, peace did not bring prosperity. Sudden demobilisation and a fall in demand for goods brought unemployment, poverty and riots. As always, however, individual reactions to the crisis varied.

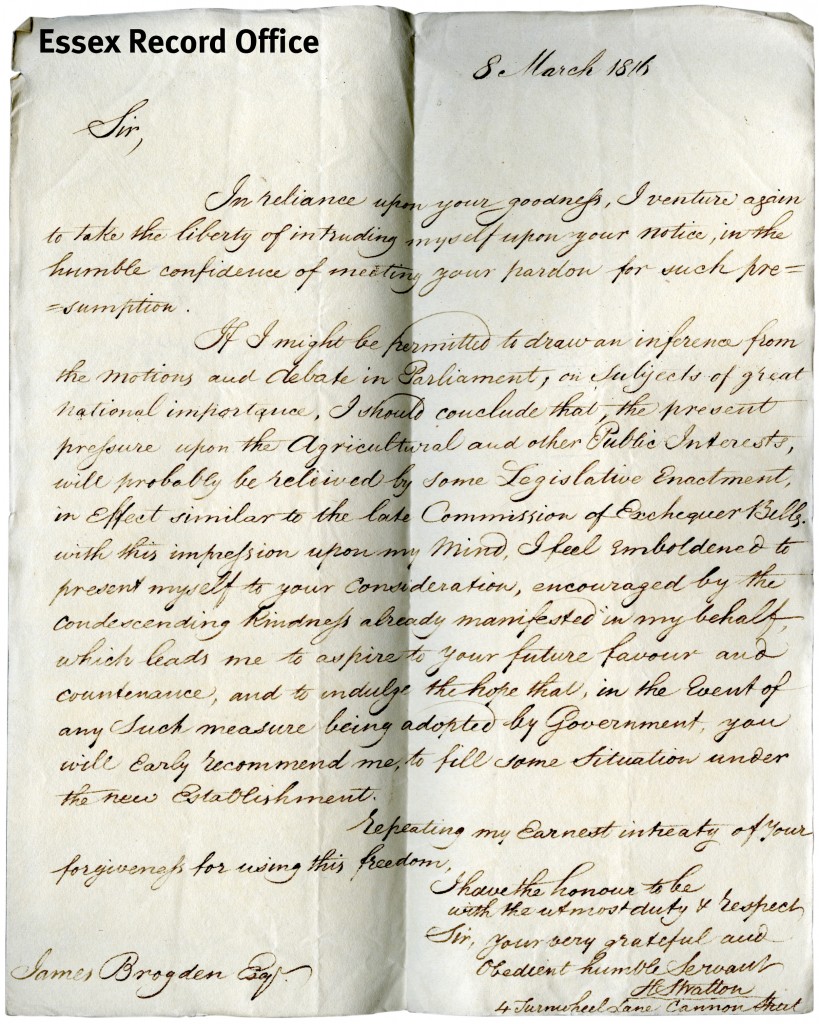

One response was to make use of the patronage networks that ran through society and government. Brogden himself was a client of the Duke of Northumberland, the major landowner at Launceston, but as a government MP and chairman of the Ways and Means Committee he too received many requests for patronage and support.

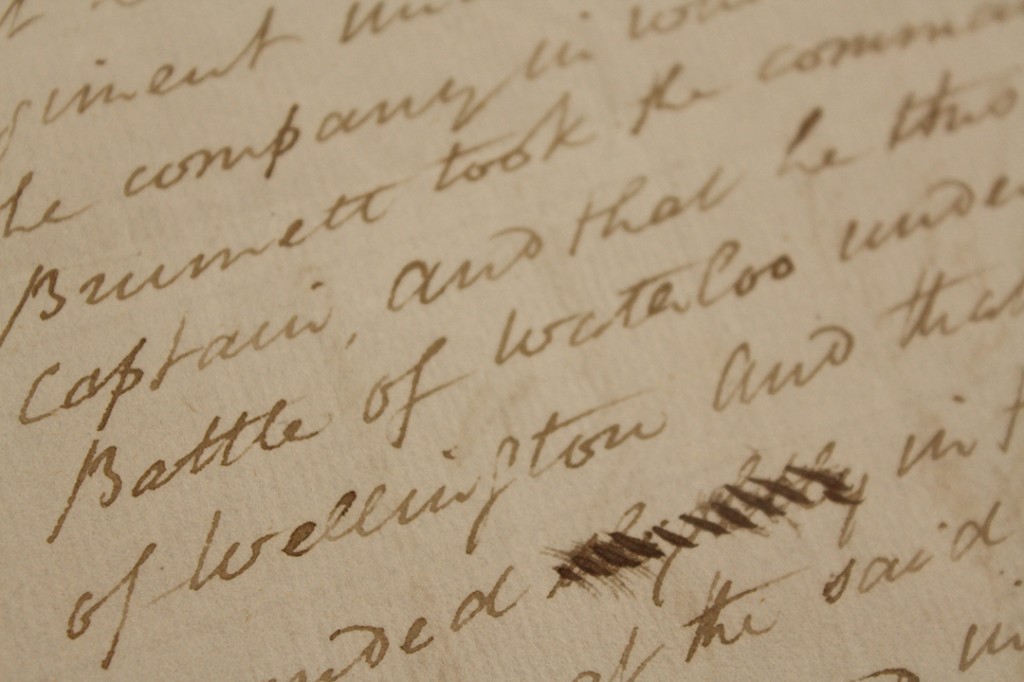

In our first letter, from March 1816, one H. Stratton wrote from London hoping for a job in the government service, stimulating the economy: ‘the present pressure upon the Agricultural and other Public Interests will probably be relieved by some Legislative Enactment … similar to the late Commission of Exchequer Bills’, and he desired ‘to fill some situation under the new Establishment’. Evidently this was not his first attempt (‘I venture again to take the liberty of intruding myself upon your notice’), but what resulted from it we do not know.

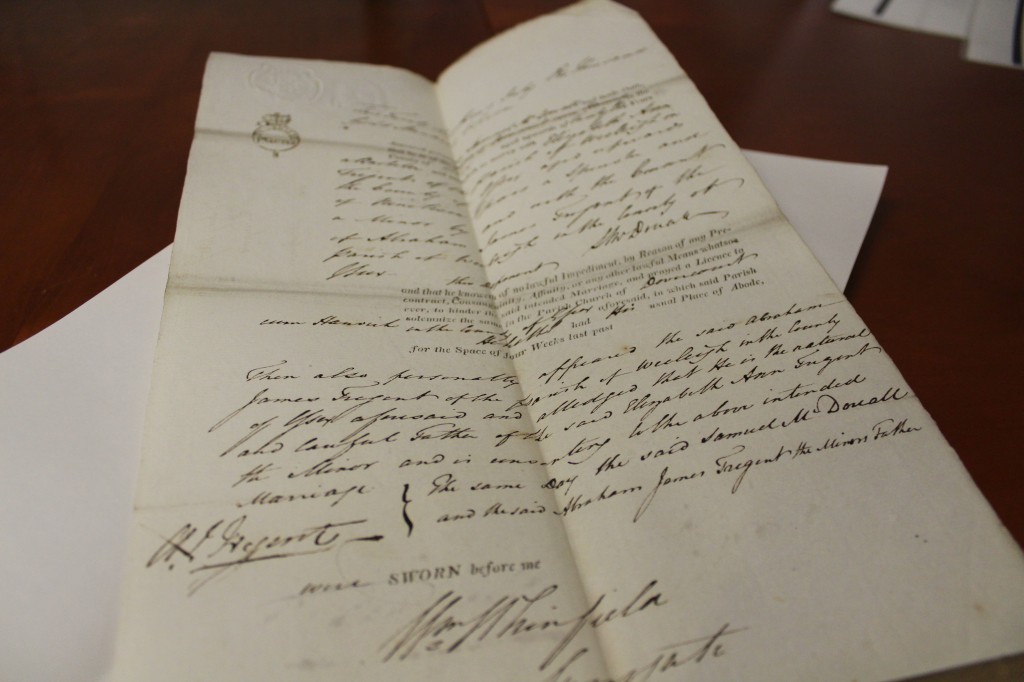

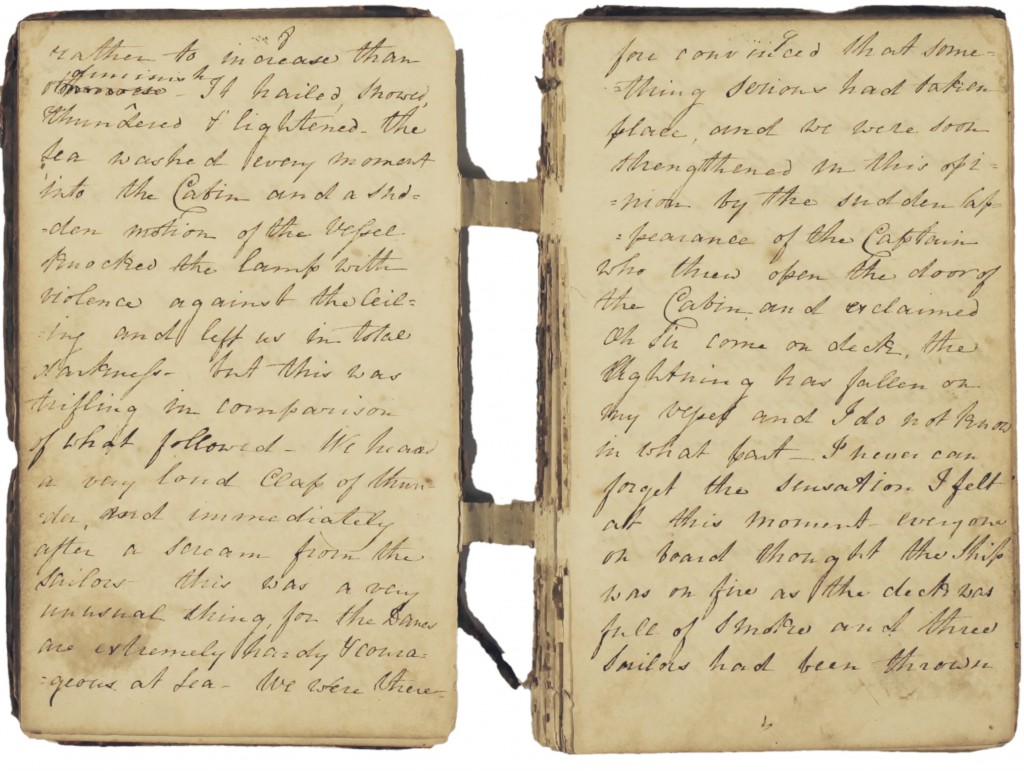

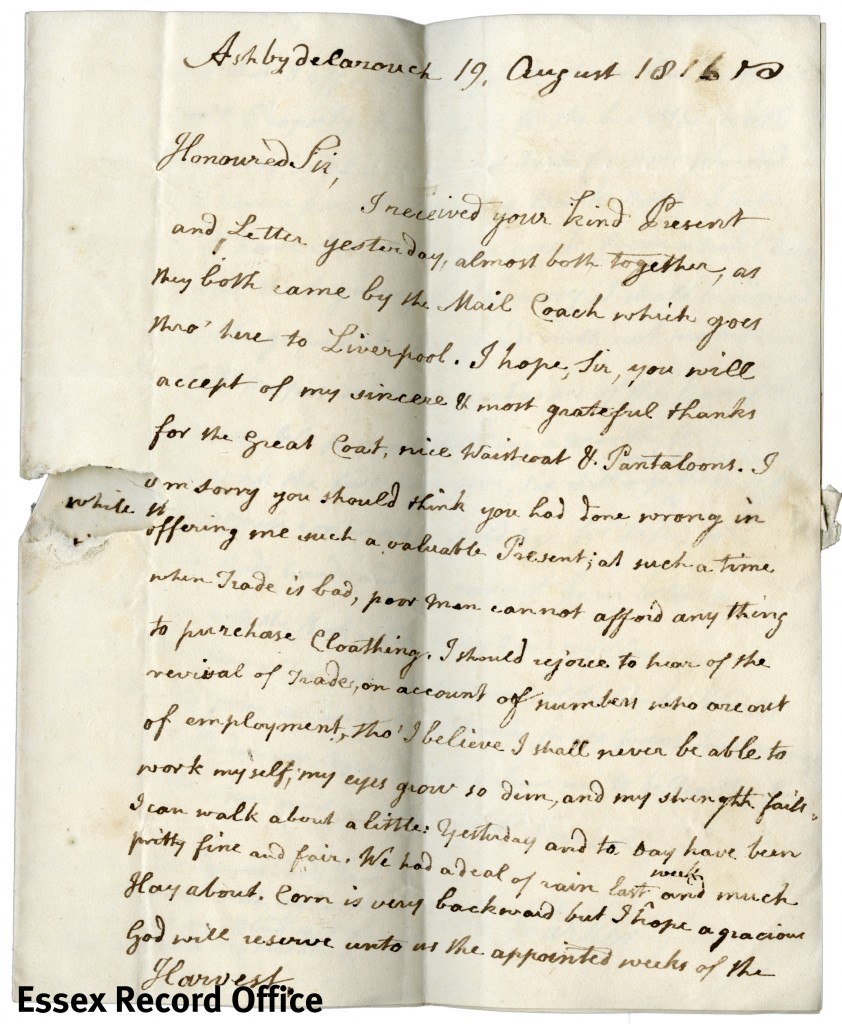

Our second correspondent, from August 1816, was of a different kind. John Parker of Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire had a longstanding connection with Brogden, whose family home was nearby at Narborough. When Brogden’s mother died in 1814, the MP had sent Parker a £5 note to buy mourning, earning a tribute for ‘taking notice of a poor old man, and … numbering him among your most intimate friends’. In 1816 Parker was 80 years old and in failing health. Just a week before the present letter, he had complained to Brogden that ‘I cannot see to work in the Frame [presumably he was a handloom weaver], and if I could I do not know that I could get work, great numbers are out of work of all Trades …’

Now Parker gives thanks for the gift of a coat, waistcoat and pantaloons: ‘when Trade is bad, [a] poor man cannot afford any thing to purchase Cloathing. I should rejoice to hear of the revival of Trade …’ Besides Brogden’s charity and 6 shillings a week from a sick club (shortly to fall to the club’s old age rate of 4 shillings), he relied on a small amount of invested capital.

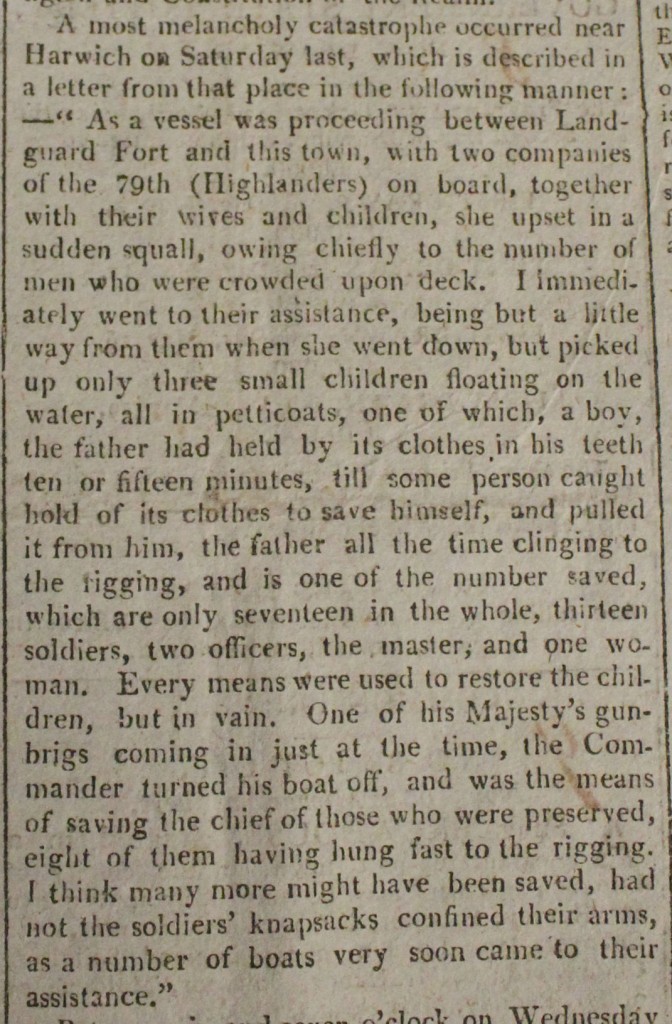

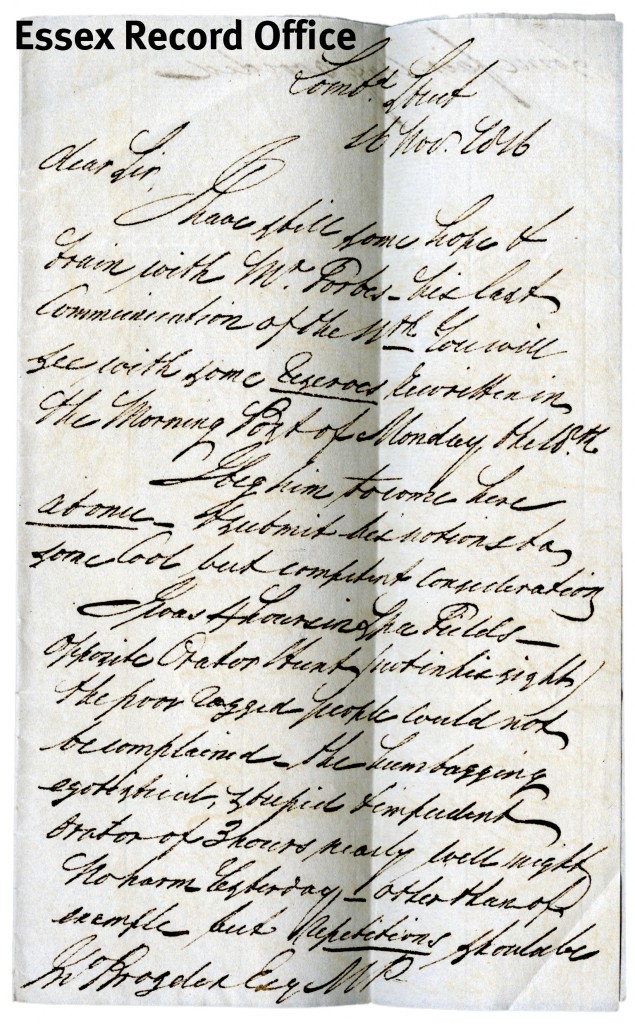

Those without capital or connections had few options. In our third letter, from November 1816, an un-named correspondent reported a very different reaction to the crisis. He had spent 3 hours at Spa Fields in London listening to the political reformer Henry (‘Orator’) Hunt address a public gathering: ‘the poor ragged people could not be complained [of] – the humbugging egotistical, stupid & impudent orator … nearly well might’. A second meeting at Spa Fields in December descended into rioting and a march on the Tower of London.

In the short term the government responded with repression, and an economic revival in 1817 helped to calm the situation. The wider question of how to create a stable politics, able to respond to economic shocks, remained.

The three letters will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout July 2016.