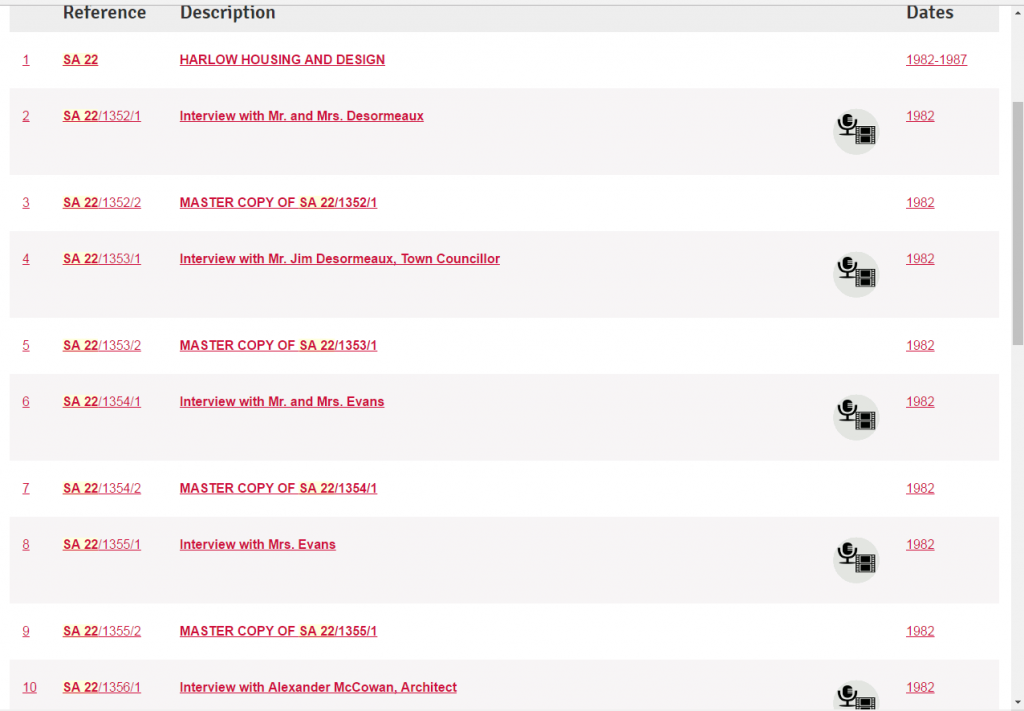

Project Archivist, Hector Mir has been working tirelessly this year to catalogue the records of the Harlow Development Corporation with the full catalogue ready to be launched on the 1st December this year on Essex Archives Online. This project has been made possible by an Archives Revealed cataloguing grant from The National Archives.

In his post below Hector explores the records of one of Harlow’s most notable features, it’s fantastic sculpture.

Since its very beginning in 1947, the Harlow Development Corporation and its General Planner, Sir Frederick Gibberd, acquired a firm commitment to link the new town they were building with the culture and the arts. This aim is especially visible in respect of sculpture. From as early as 1951 up to the present day, the new town has filled up its streets with the works of some of the most renowned sculptors.

Such important activity appears well referenced in the papers of the Harlow Development Corporation Archive, which the Essex Record Office has now opened up by creating a new online catalogue (A/TH).

The main source comes from the file “Sculpture” (A/TH 2/6/1), which includes papers relating to “Contrapuntal Forms” by Barbara Hepsworth (1951), murals from the Festival of Britain Exhibitions (1952), Centaur’s statue (1953), Henry Moore’s “Family Group” sculpture (1955-1956), Early Memorial (1959), “Kore” sculpture (1975), sculptured head of Sir Frederick Gibberd (1979).

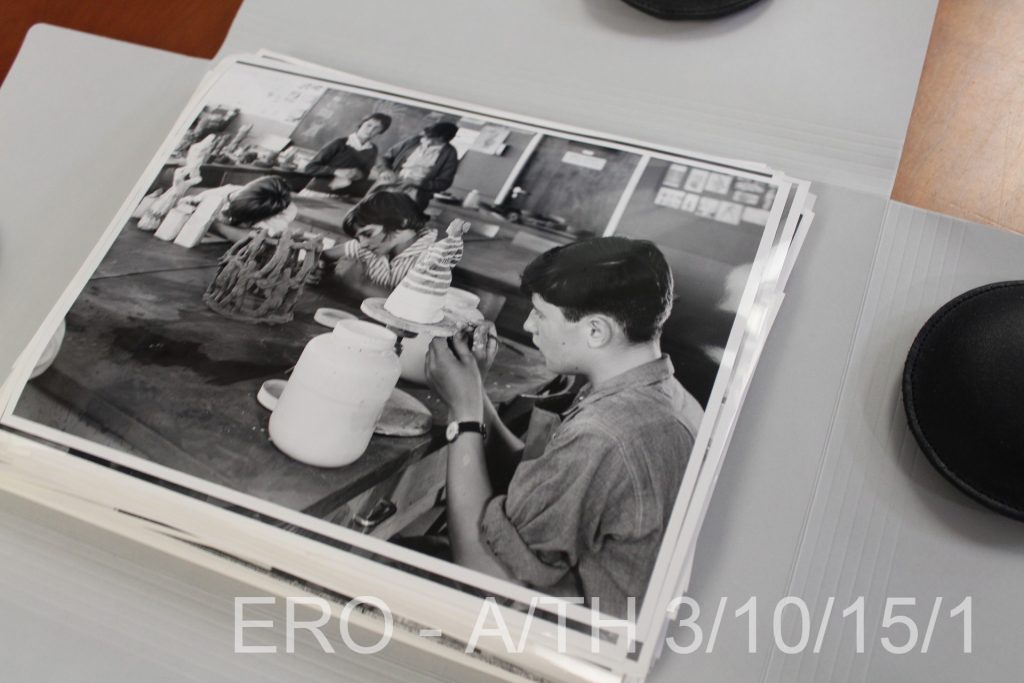

Scattered information on sculptures, including lists of Harlow Arts Trust sculptures (June 1968) can be found in the files related to Patrons of the Arts – Harlow Arts Trust (A/TH 3/2/8/33-36), covering the whole existence of the Corporation (1948-1980). The is also a file on Play Sculptures in the sixties (A/TH 3/3/3/4).

A sculpture unveiling has been always an important ceremony. We keep the files of three of those events: the unveiling of Henry Moore’s “Family Group” sculpture in 1956 (A/TH 3/8/3/54), which includes invitation card and programme; “Kore” sculpture in 1975 (A/TH 3/8/3/2); and the unveiling of an obelisk at Broad Walk in 1980 (A/TH 3/8/3/50 and A/TH 3/11/65), including invitation card, programme and diagram of construction.

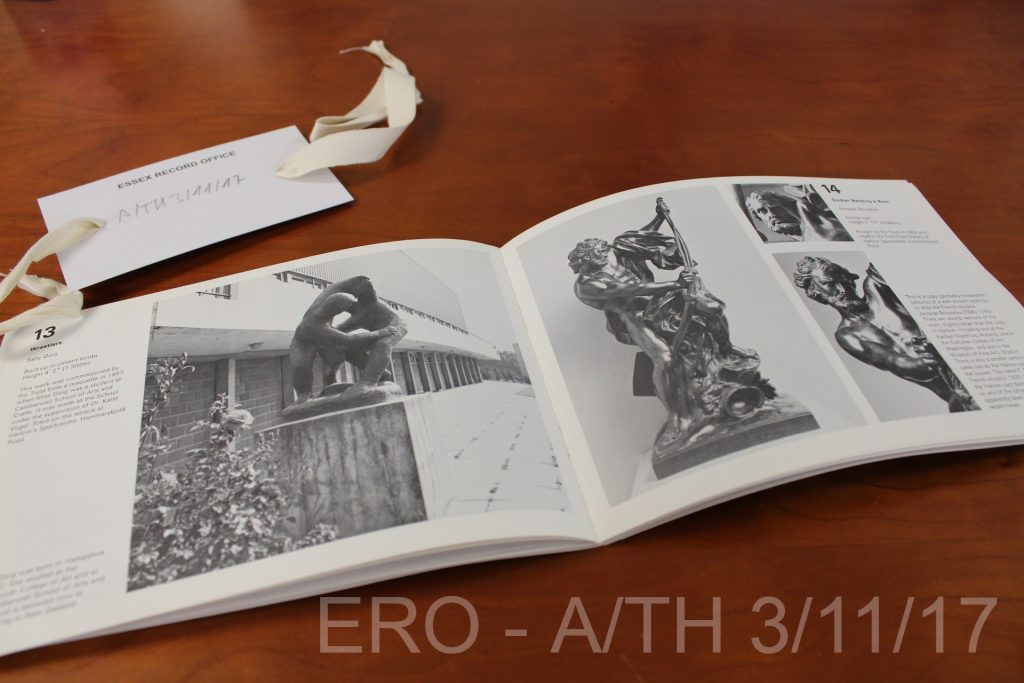

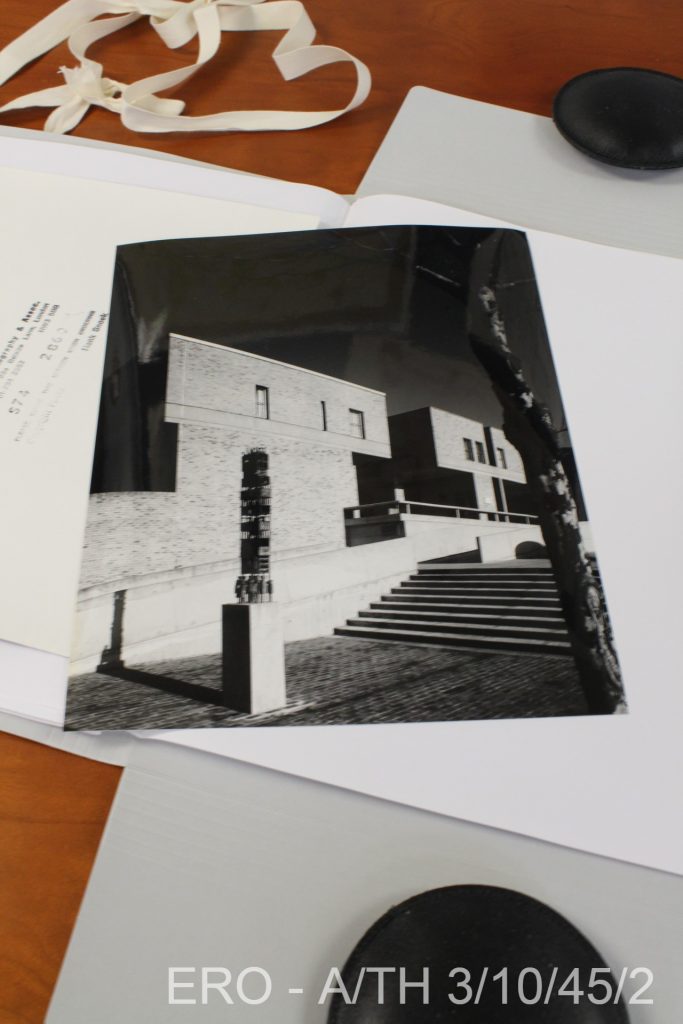

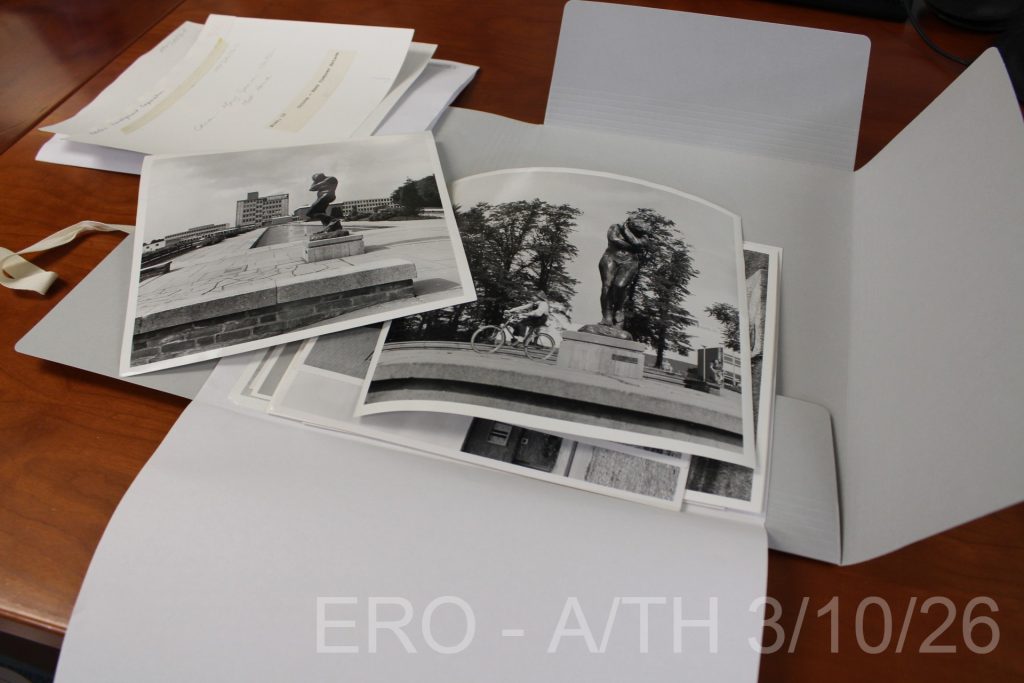

Sculptures are also well represented in the Social Development Department Photographic Collection (A/TH 3/10). Two files with 30 photographs cover specifically the subject (A/TH 3/10/26 and A/TH 3/10/44), with pictures of “Family Group” and Bronze Cross by Henry Moore, “Wrestlers”, “Chiron” by Mary Spencer Watson, Eve by Auguste Rodin, “Contrapuntal Forms” by Barbara Hepworth, “Help” by F.E. McWilliam, “High Flying” by Antanas Brazdys, “Kore” by Betty Rea, “Motif No. 3” by Henry Moore, “Trigon” by Lynch Chadwick, “Echo” by Antanas Brazdys, “The Boar” by Elisabeth Fink, Fountain Figure and Lion by Antoine-Louise Barye. As well as another file with 12 photographs of Henry Moore’s “Family Group” Sculpture (A/TH 3/10/25). There are also loose photographs of “The Sheep Shearer” by Ralph Brown, outside Ladyshot Common Room (A/TH 3/10/8/72) and “Boy eating apple” a statue in bronze by Percy Portsmouth, commissioned by the Harlow Art Trust and situated on the wall of the Mark Hall Branch Library in The Stow (A/TH 3/10/9/10).

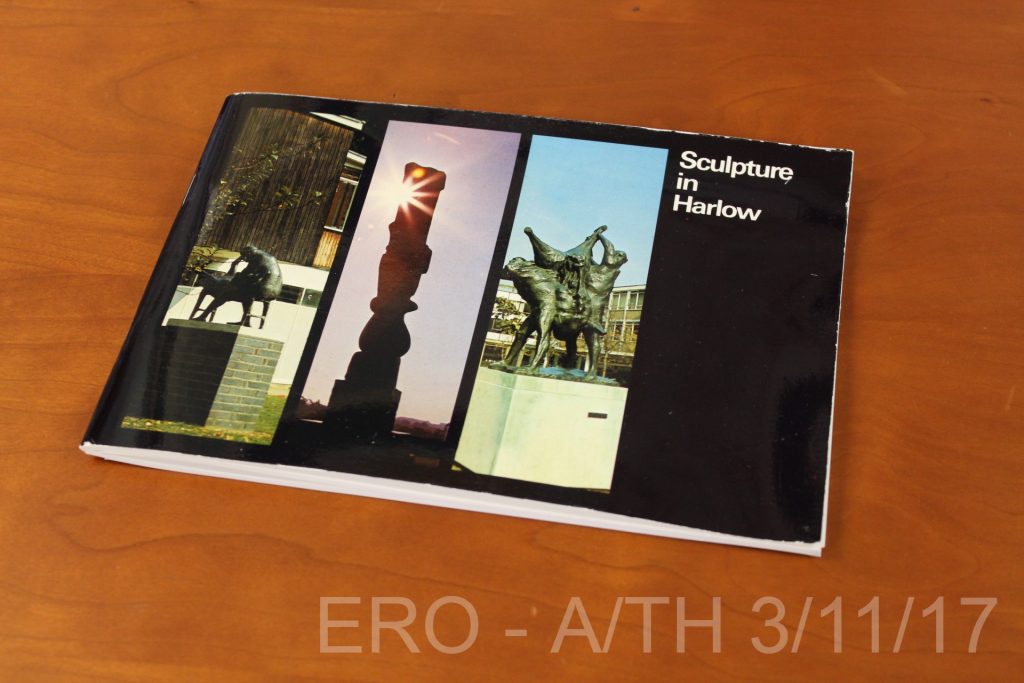

Finally, an excellent overview can be found in the 31 page booklet ‘Sculpture in Harlow’ (A/TH 3/11/17), published by Harlow Development Corporation in 1973.