This autumn will see an exciting new development for us as we welcome a new member of our team, who just happens to be over 3,000 miles away.

Linda MacIver will be working for us based in Boston, Massachusetts, to help people in New England who want to trace their English, and especially Essex, ancestors. Linda has many years of experience as both a librarian and as a teacher of local history and genealogy, so we are excited that she will be working with us.

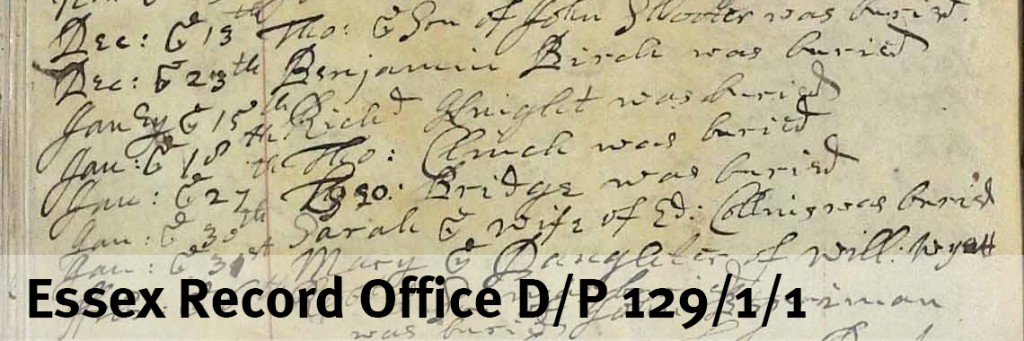

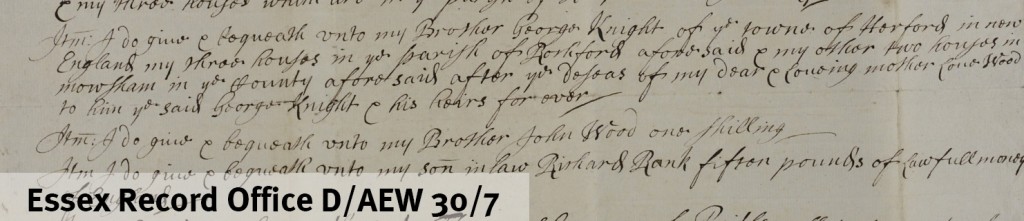

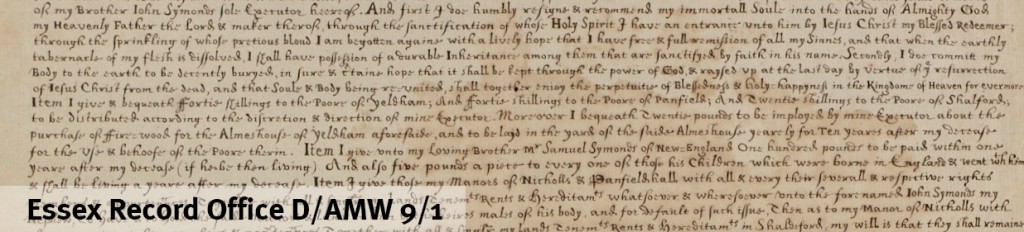

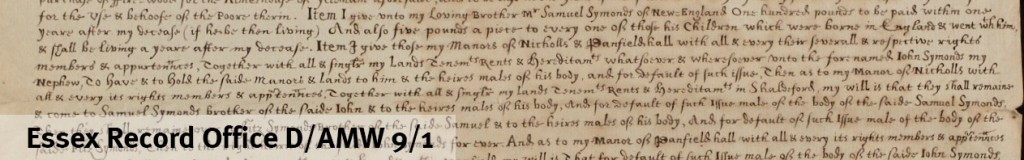

Linda will be available to give talks and attend genealogy fairs (and anything else you might want to invite her to!). She will be introducing people to the historical documents from our collection which can be accessed online anywhere in the world through our subscription service, and to talk about some of the connections between Essex and New England.

We first met Linda last summer when two of our number, Neil Wiffen and Allyson Lewis, paid a flying visit to Boston to meet American researchers who use our collections. Linda was then working at Boston Public Library, one of the venues Neil and Allyson gave a talk, and it was from that visit that the idea of her being our representative in New England emerged.

As has become traditional with new members of our team, we thought we would get to know Linda a little better:

Hello Linda, tell us a bit about yourself.

My professional career started as a high school teacher of U.S. and Modern European History. Unexpectedly I was recruited to serve as the school librarian and my career would take a “librarian train ride” through stops in academic, corporate and, finally, a public library with research library status, one of only two such public libraries in the U.S., New York and Boston. That move brought all of my intellectual background together, using subject expertise in business and social sciences areas, as a frontline librarian and as a researcher. It was my original interest in history that turned my attention to local history and, finally, family history. For the past five years I have developed the Library’s genealogy program, not only through two very successful lecture series, but by teaching genealogy classes for our patrons, bringing me back full circle to my teaching roots.

What is your favourite period of history?

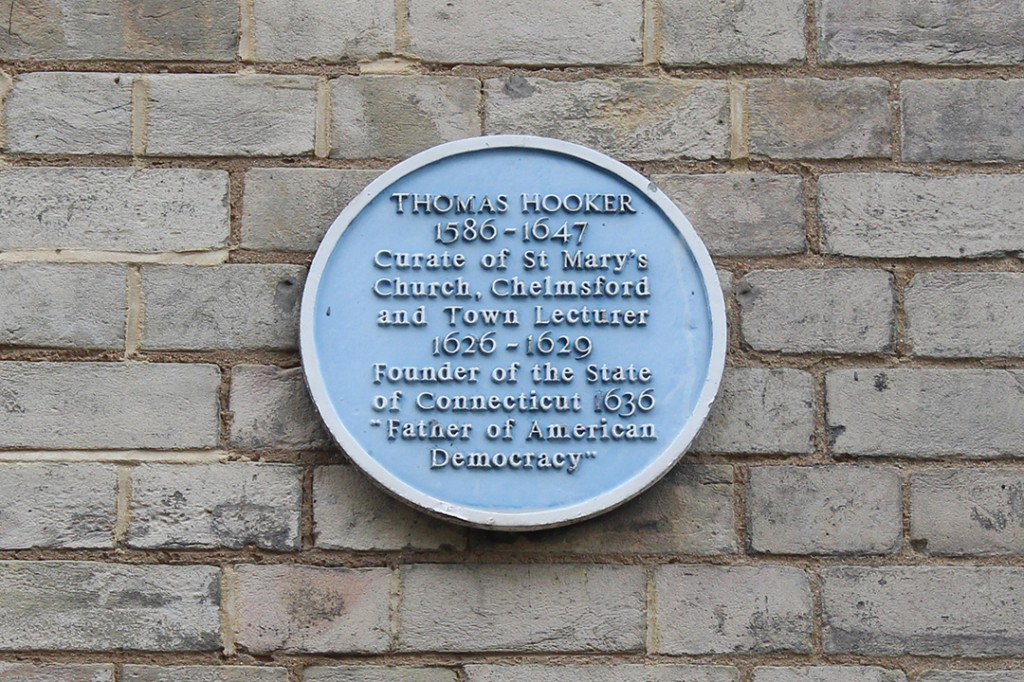

As a teen I was enthralled with ancient history and the rise of civilization, partly because I thought I wanted to be an archaeologist and partly because I had great teacher in the subject. Then I took Modern European History and had another great teacher. Both had taught with the Socratic method, making us think through the reasons that caused cultural development and change. This critical thinking process made history come alive. As a young teacher myself, I started travelling, mostly to England a baker’s dozen times. London became my home away from home, and my favourite period became the evolution of the constitutional monarchy and democratic movements in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Do you know if you have English Ancestors yourself?

From my “Mac” name, we know I have mainly Scottish and Irish DNA. Historically, the MacIvers left Uig in the Hebrides in the early 1800’s for Quebec province, my direct line crossing the border to northern New Hampshire just before 1900. My maternal heritage is Anglo-Saxon. Today the surname is Arlin, deriving from Harland or Hoarland. Family folklore says we come from the Great Migration immigrant George Harland of Virginia, but I have yet to make the connection. It is more likely that I do, in fact, have Essex connections since the 1891 census actually finds more Arlins in Essex and Suffolk than in any other part of England! My English connections are many: one of my favourite spots in the world is Salisbury Cathedral; I spent a summer in England studying the “History of the Book” and visiting many English libraries and printers; and I was born in Manchester, New Hampshire, the “Manchester of America.”

How are you going to be helping people in New England discover their English and Essex ancestors?

It is no secret that there is great interest for New Englanders to make connections to their English roots. Neil and Allyson’s whirlwind visit last year was proof of that. I hope to further encourage that interest by bringing them news of the ways they can make those connections as I lecture around the region, exhibit at genealogy conferences and perhaps even do some “hands on” training of the free and subscription services of ERO.

What do you like to do outside of work?

Actually, what I do outside of work is quite similar to what I do for work. Working on my own family history can sometimes be a rare event since I am so often working on others or teaching them how to research. I hope to do more of my own. I am also Secretary of the Massachusetts Genealogical Council. In the fall I will start to volunteer at the Boston Registry where I will be surrounded by Boston civil records from the 1600s on. Not quite as old as some of ERO’s holdings, but impressive from this side of the pond. Otherwise, from Boston, one MUST BE a sports addict! We tend to live and die with our teams; for me especially the Red Sox and New England Patriots. But I am fortunate to live in one of the cultural meccas of the world and enjoy the Boston Symphony and Pops, musical theatre, and folk and “Big Band” concerts.

If you are in the Boston, Massachusetts area and would like to book Linda for a talk on Tracing Your English Ancestors, get in touch with us on ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk

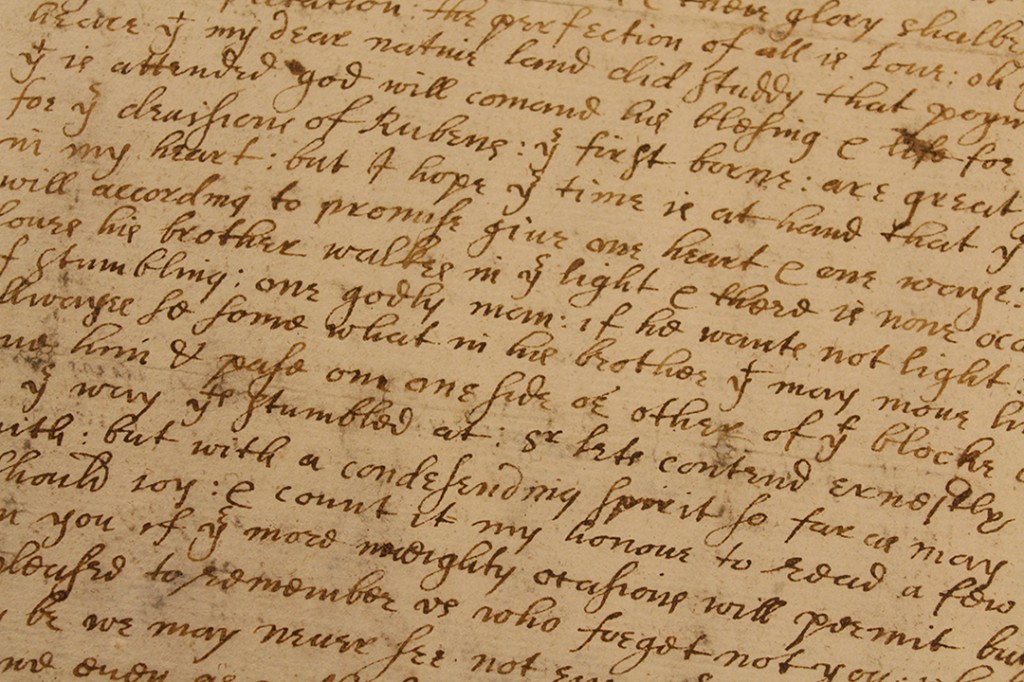

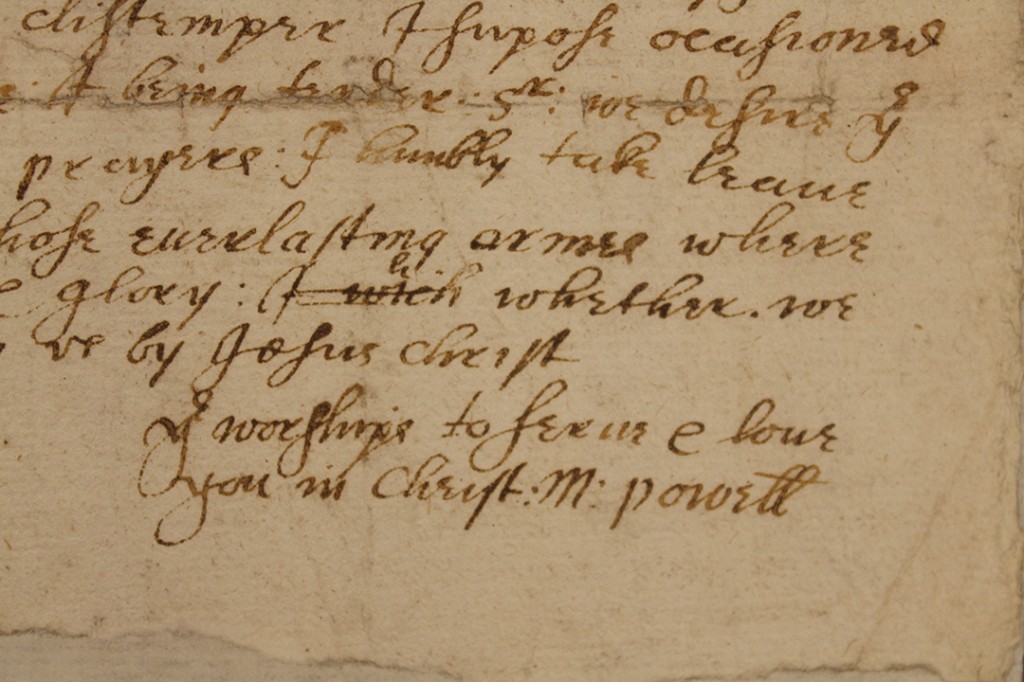

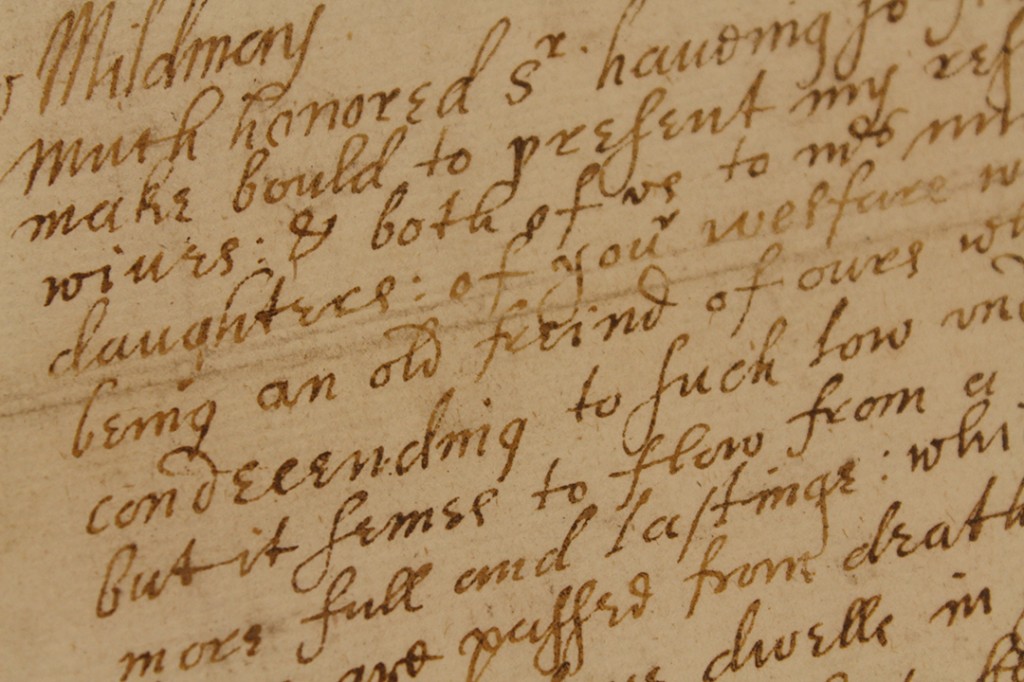

The Great Migration Directory, by Robert Charles Anderson, lists all those families and unattached individuals, about 5600, who came to New England between 1620 and 1640 as part of the Great Migration. Each entry provides data on English origin (if known), year of migration, residences in New England, and the best treatment of that immigrant in the published secondary literature. The book may be ordered through the New England Historic Genealogical Society

The Great Migration Directory, by Robert Charles Anderson, lists all those families and unattached individuals, about 5600, who came to New England between 1620 and 1640 as part of the Great Migration. Each entry provides data on English origin (if known), year of migration, residences in New England, and the best treatment of that immigrant in the published secondary literature. The book may be ordered through the New England Historic Genealogical Society