Katharine Schofield, Archivist

(D/DP M150)

We are publishing October’s Document of the Month a little early since we are excited about our conference Norman Essex: what did the Normans do for us? taking place this Saturday (1 October 2016). Despite the fact that it dates from about 200 years later, this document is named after that most famous of Norman documents – Domesday Book.

Compiled in 1086, Domesday Book records the lands in the possession of the king’s tenants-in-chief; Norman followers who were rewarded with land in return for military support. By the end of the 12th century Domesday Book was held in sufficient respect to be kept with other important Exchequer documents and the Great Seal. In c.1179 Henry II’s treasure Richard fitzNeal or fitzNigel described in his Dialogue of the Exchequer how it was known to the ‘native English’ as Domesday Book ‘not because it contains decisions on various difficult points, but because its decisions, like those of the Last Judgement, are unalterable.’

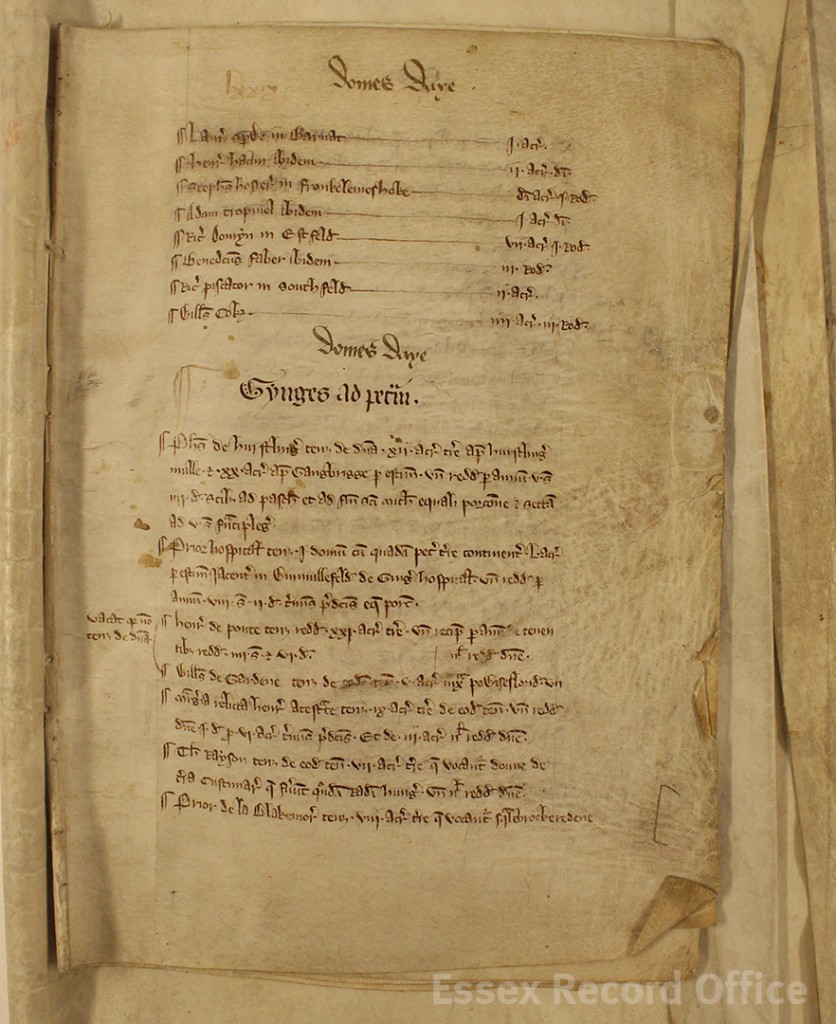

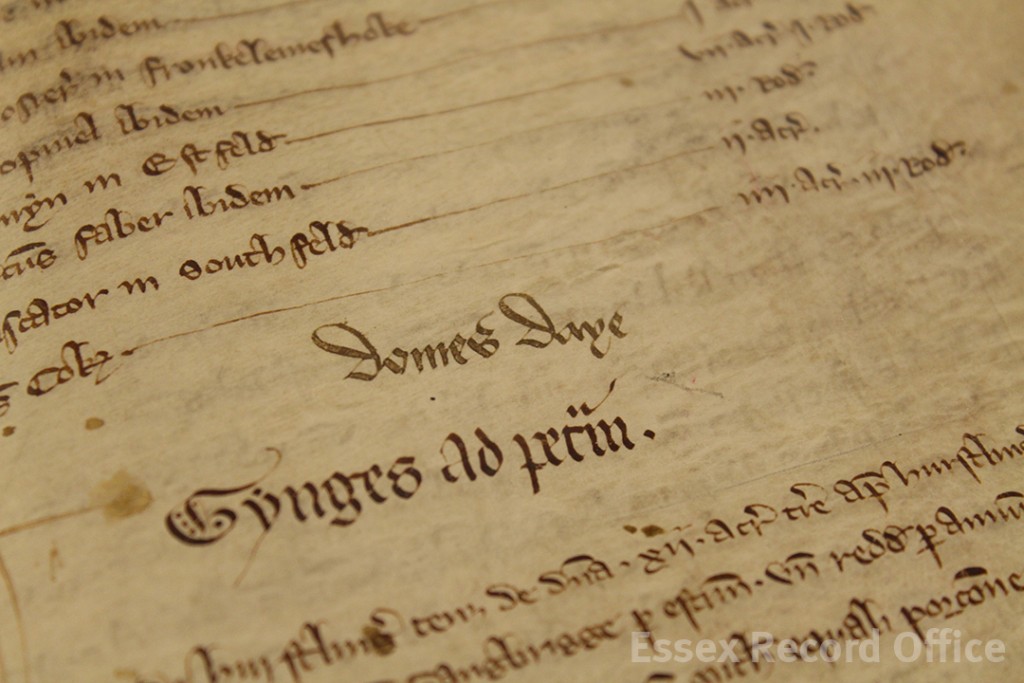

Our Document of the Month follows in the footsteps of Domesday Book, and it is clearly headed with the words ‘domes daye’. It is the Ingatestone portion of the ‘Barking Domesday’, dating from about 1275. Only two parts of the survey survive, a 15th century copy of the manor of Bulphan and this from the manor of Ingatestone which is stitched into a rental. The survey names the tenants, gives a brief note of their landholdings and rent and then a much more detailed account of the labour services such as ploughing, hoeing, making hay, reaping and even gathering nuts that they owed to the lord of the manor and the times of year when they were due.

Our Document of the Month follows in the footsteps of Domesday Book, and it is clearly headed with the words ‘domes daye’. It is the Ingatestone portion of the ‘Barking Domesday’, dating from about 1275. Only two parts of the survey survive, a 15th century copy of the manor of Bulphan and this from the manor of Ingatestone which is stitched into a rental. The survey names the tenants, gives a brief note of their landholdings and rent and then a much more detailed account of the labour services such as ploughing, hoeing, making hay, reaping and even gathering nuts that they owed to the lord of the manor and the times of year when they were due.

Although the words Domesday look as though they have been written in a different hand we do know that on 28 October 1322 the manorial court required the that the ‘Domesdaye de Berkyng’ be produced to answer a question about succession dues owed to the manor.

To find out more about what the original Domesdaye survey tells us about Essex, join us for Norman Essex this Saturday (1 October), and do have a look at the Barking Domesday if you visit the Searchroom during the coming month.

![The deeds are not dated but this one must date from before the second half of 1140, before Geoffrey was made Earl of Essex, as he is named only as G de Mand[eville]. In this deed de Mandeville grants the land of Alan de Scheperitha to Eustace and Humphrey de Barentun. (D/DBa T2/1)](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/D-DBa-T2-1-1080-watermarked-1024x683.jpg)

![In this second deed Geoffrey he is described as Gaufr[ido] Comes Essexe (Geoffrey, Earl of Essex). In this document he confirms a grant of lands in Hatfield [Broad Oak] and Writtle to Humphrey de Barentun. (D/Dba T2/3)](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/D-DBa-T2-3-1080-watermarked-1024x582.jpg)