In August 918 years ago, the king of England died in suspicious circumstances. Here, our medieval specialist Katharine Schofield discusses what may or may not have happened that day, and the Essex connections of the man rumoured to have killed the king.

On 2 August 1100 William II was killed while hunting in the New Forest. William (also known as William Rufus) was the son of William the Conqueror, and had inherited the kingdom of England on the death of his father in 1087.

The earliest account of his death in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that he was shot by an arrow by one of his men. Later chroniclers named Walter Tirel as the man who fired the fatal shot. Opinions vary as to whether Rufus met his death by accident or design.

Tirel was a renowned bowman; one account of William’s death records that at the start of the day’s hunting the king was presented with six arrows, two of which he gave to Tirel with the words Bon archer, bonnes fleches [To the good archer, the good arrows].

Other chroniclers record that Tirel let off a wild shot at a stag which he missed, hitting the king instead. Tirel took no chances and fled to France, according to legend having the horseshoes of his horse reversed to throw off any pursuit. In France he always maintained his innocence. Abbot Suger of St. Denis who knew Tirel in France recorded ‘I have often heard him, when he had nothing to fear nor to hope, solemnly swear that on the day in question he was not in the part of the forest where the king was hunting, nor ever saw him in the forest at all.’

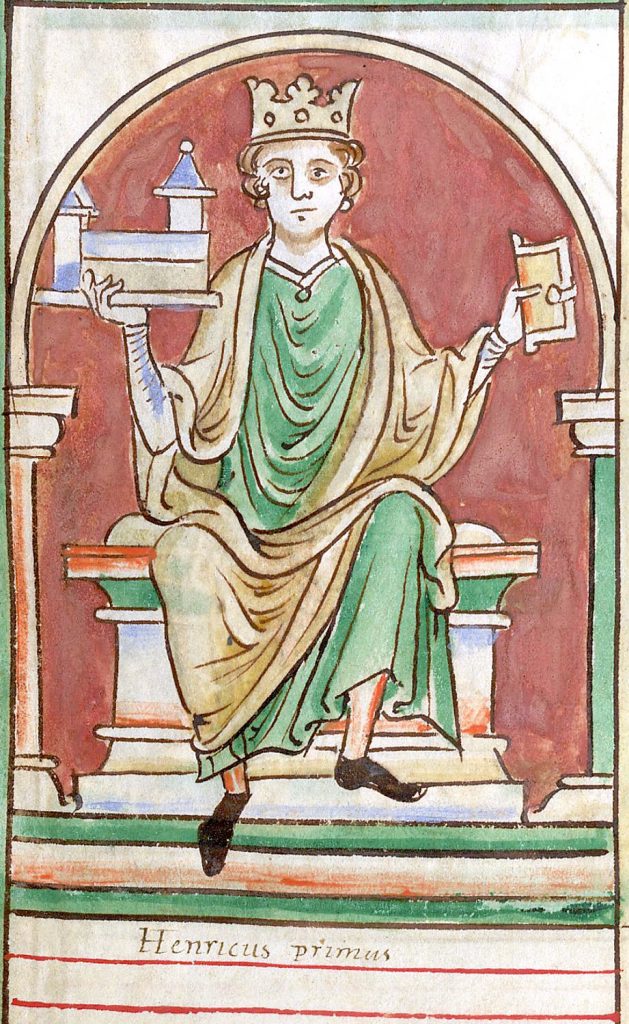

What is not in doubt is that Rufus’ younger brother Henry (Henry I) was the main beneficiary. Henry was part of the hunting party on that day and he was able to secure the Treasury (then held at Winchester) the same day and had himself crowned king at Westminster Abbey on 5 August, just three days after his brother’s death.

Illustration of Henry I by Matthew Paris

Walter Tirel (or Tyrell) is thought to have originated from Poix in Picardy and may have been the same Walter Tirel named as holding the manor of Langham, in north east Essex, (Laingeham) in Domesday Book. The Revd. Philip Morant in The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex (1768) was rather dubious as to whether there was a connection, while another historian with Essex connections, J.H. Round writing in 1895 was more certain that they were the same.

The Domesday Book recorded in 1086 that the manor of Langham was 2½ hides in extent (roughly 300 acres), with 17 villeins and 27 bordars. There was wood for 1,000 pigs, 40 acres of meadow, two mills, 22 cattle, 80 pigs, 200 sheep and 80 goats. The resources of the manor were mostly larger than they had been before the Norman Conquest, and its value had increased from £12 to £15, making it quite valuable; by comparison, the manor of Chelmsford was valued at £8 and Maldon at £12.

Tirel held the manor from Richard son of Count Gilbert, also known in Domesday Book as Richard fitzGilbert or Richard of Tonbridge, and is later more familiarly known as Richard de Clare. It is likely that Tirel acquired the manor through his wife Adeliza, Richard’s daughter and this explains why he had such a valuable holding.

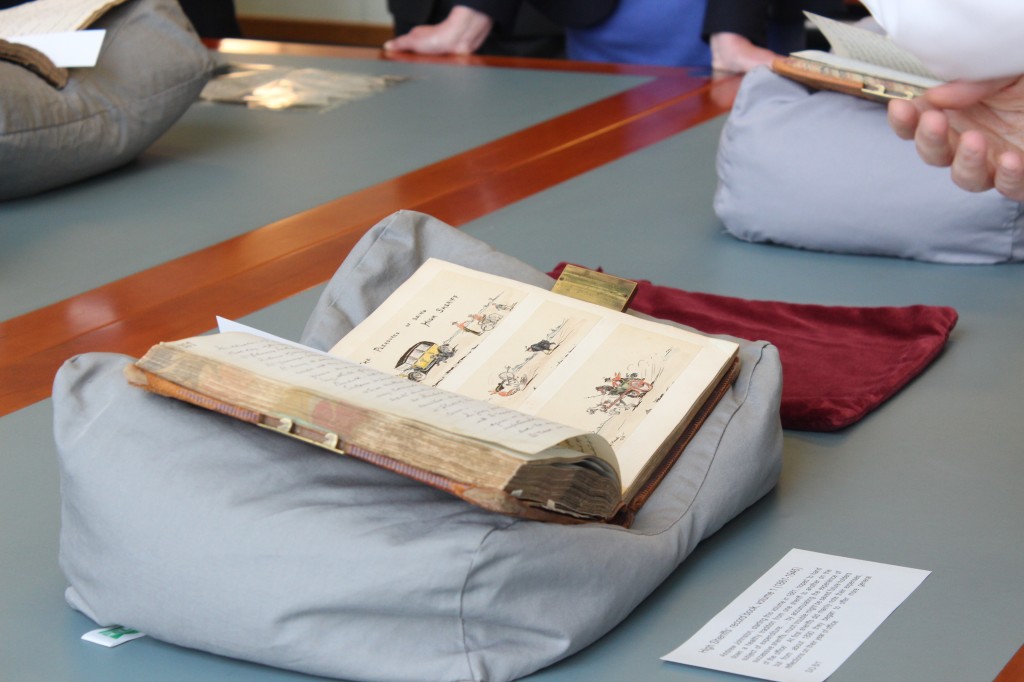

The Pipe Roll of 1130 records that Adeliza, by then a widow, was still in possession of Langham and in 1147 their son Hugh Tirel sold it to Gervase de Cornhill, before embarking on the Second Crusade. In 1189 Richard I granted Gervase’s son Henry permission to enclose woods there to create a park. The manor remained part of the Honour of Clare, while passing through the hands of different owners. In the late 14th century it passed to the de la Pole family and remained in their possession until the early 16th century. The oldest surviving court roll from the manor, 1391-1557 (D/DEl M1) begins during their ownership.

Henry VIII’s first wife Katharine of Aragon held the manor, later Langham Hall, until her death, when it passed to his third wife Jane Seymour. In 1540 it passed briefly to Thomas Cromwell and after his execution formed part of the lands granted to Anne of Cleves (Henry VIII’s fourth wife) on her divorce. In the early 17th century it was granted by Charles I to trustees of the City of London in repayment for a loan. In 1662 it was purchased by Humphrey Thayer, who Morant described as a druggist to the King and was inherited by his niece, the wife of Jacob Hinde.

While Morant was doubtful as to the connection of Walter Tirel in Langham with the Tirel who may have killed William Rufus, he was in no doubt that he was the ancestor of the Tyrell family in Essex who he described as ‘early persons of great consequence in this County; and one of the ancientist families’.

While the Tyrells did not keep Langham for more than one generation, they acquired extensive lands in Essex, as well as lands in Hampshire, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. Their lands centred on the manor of Heron in East Horndon, but Tyrells also held land in Broomfield, Springfield, Beeches at Rawreth, Hockley and Ramsden Crays.

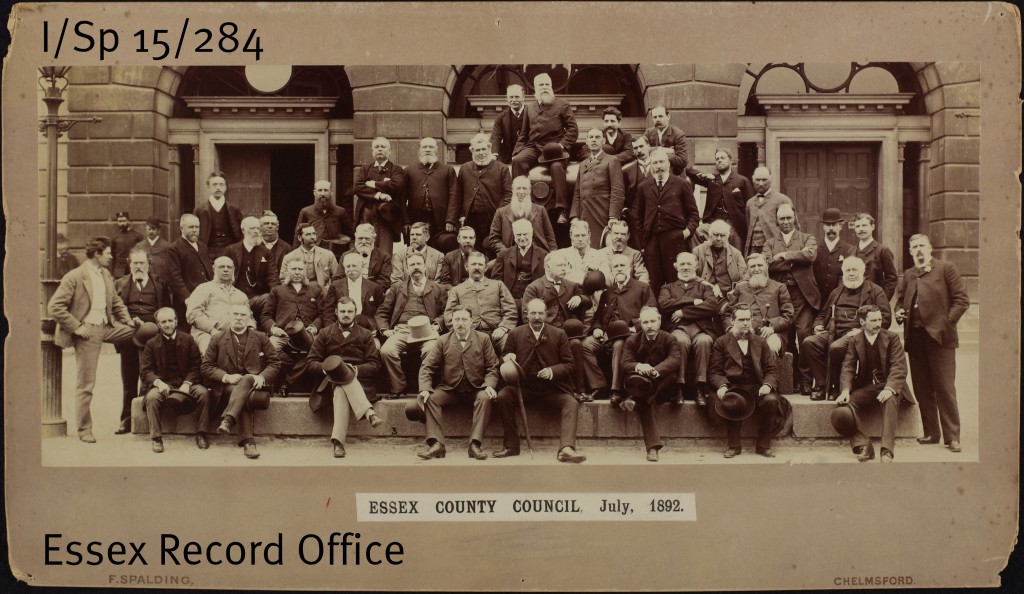

The most distinguished of the Essex Tyrells was probably Sir John Tyrell. He served as sheriff of Essex in 1413-1414 and 1437 and was elected to Parliament on a number of occasions between 1411 and 1437, serving as Speaker in 1421, 1429 and 1437. He held many posts in Essex, including acting as steward to the Stafford family and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, as well as for Clare and Thaxted during the minority of Richard, Duke of York. He was appointed a royal commissioner in the county on a number of occasions and was Chief Steward of the Duchy of Lancaster north of the Trent. Morant recorded that he served Henry V in France and in 1431 was appointed treasurer to the household of Henry VI and to his Council in France.

In a curious coincidence his grandson Sir James Tyrell was alleged to have confessed before his execution in 1502 to murdering the Princes in the Tower for Richard III.