Hannah Salisbury, Engagement and Events Manager, with thanks to Caroline Stevens for sharing extracts from Kate’s letters relating to the Battle of Passchendaele

As 2017 draws to a close we may well reflect on what the year has brought, to ourselves, our families and friends, and the wider world.

Doubtless our ancestors did the same thing 100 years ago, as the First World War dragged on into the new year.

Sister Kate Luard, an Essex nurse who volunteered for military service, had by this time been serving as a nurse on the Western Front for three years and three months. She must have seen countless soldiers suffering from all sorts of unthinkable wounds pass through her wards, and still there was no end in sight.

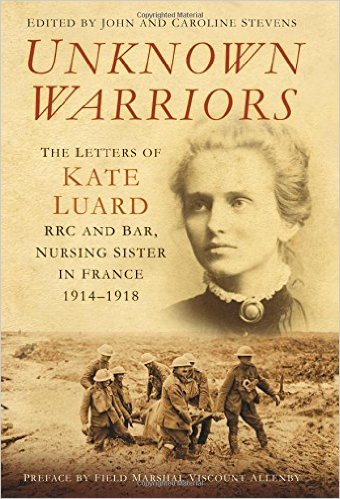

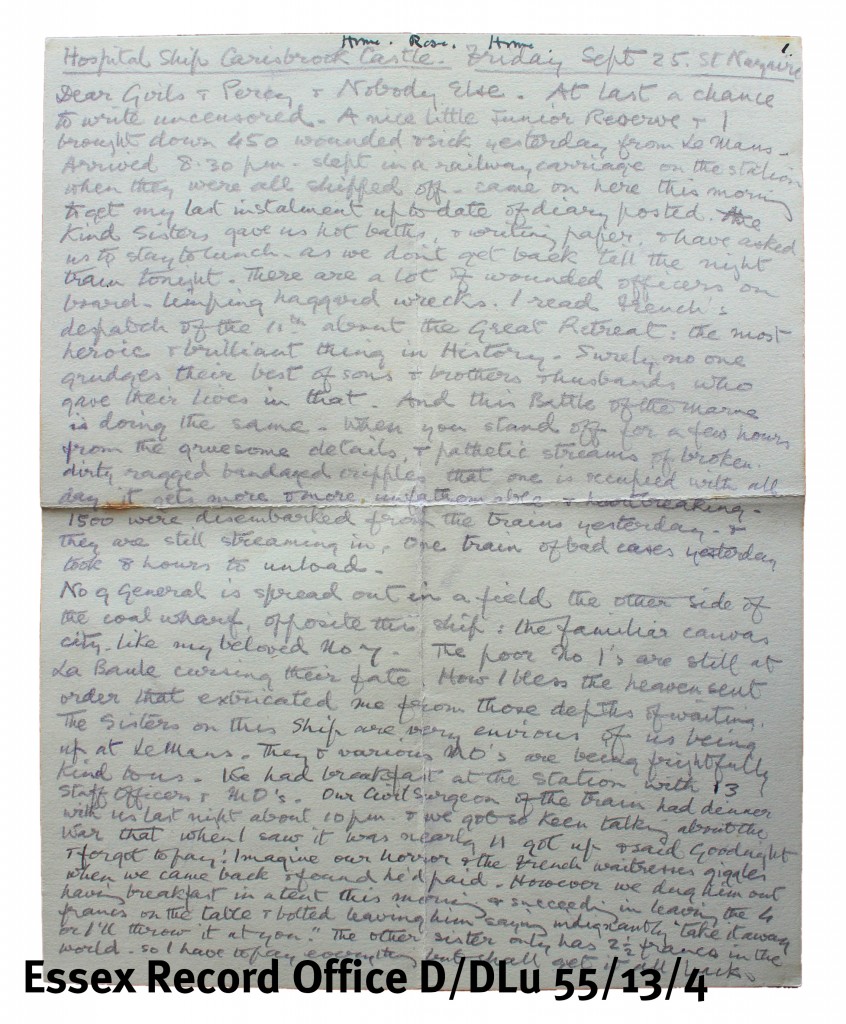

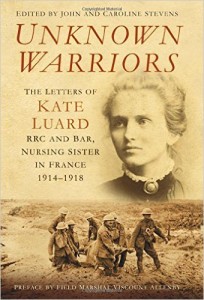

1917 brought some of the biggest challenges and most dangerous situations that Kate would face during the war, and these are detailed in the letters she sent home to her family. To help put the letters into a geographical context, please see the map at the end of this post which tracks some of the locations where Kate wrote from during 1917. Many of the letters quoted here are reproduced in Unknown Warriors: The Letters of Kate Luard, RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France, 1914-1918 – these are referenced here as UW.

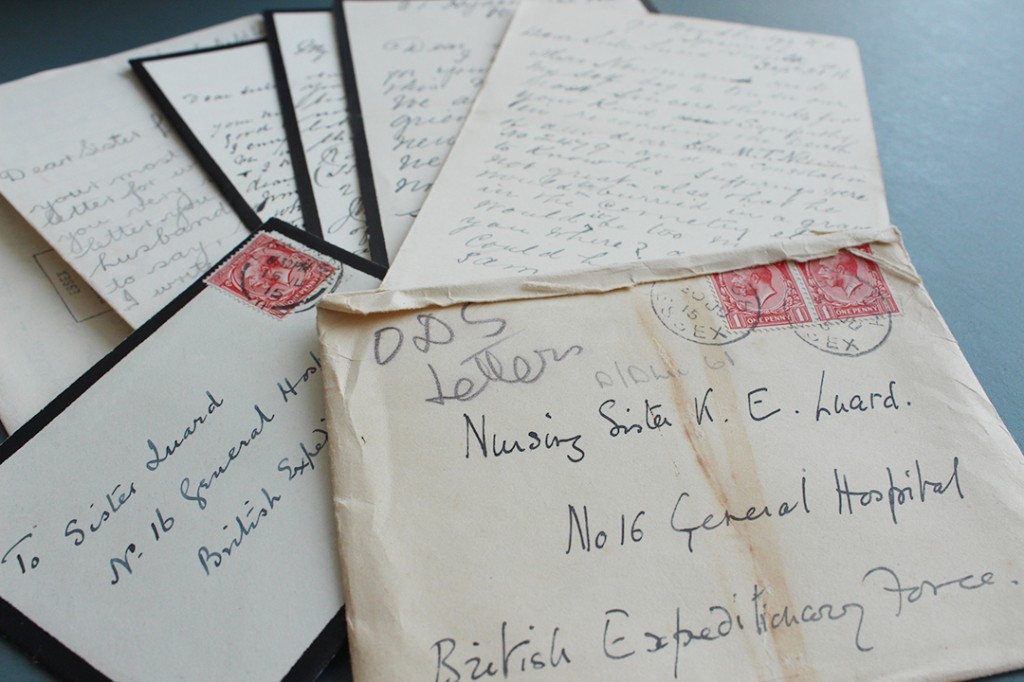

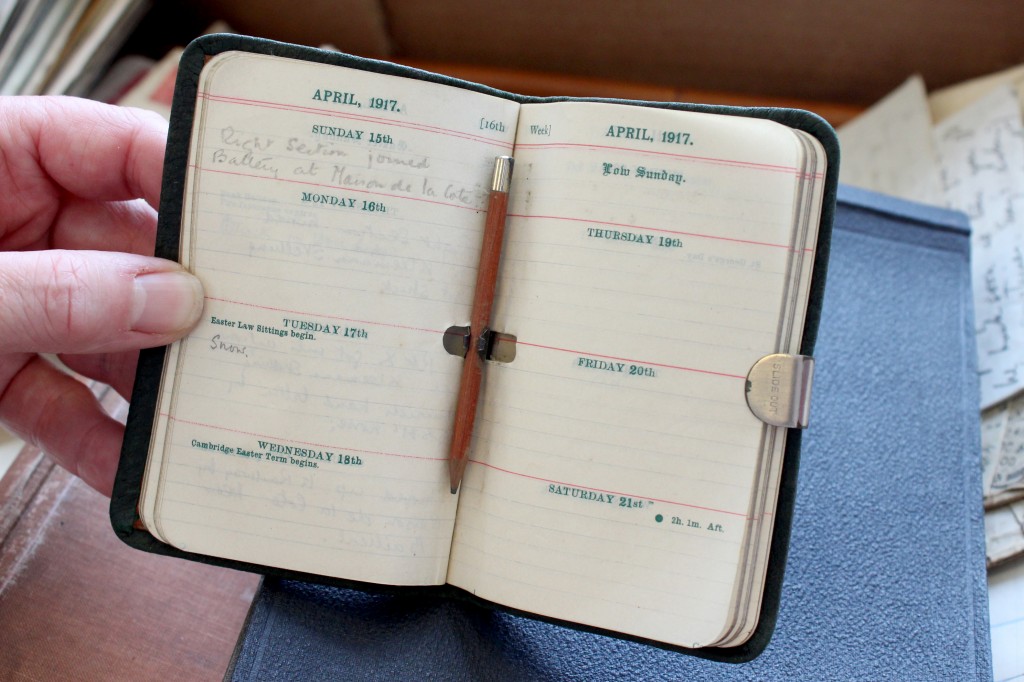

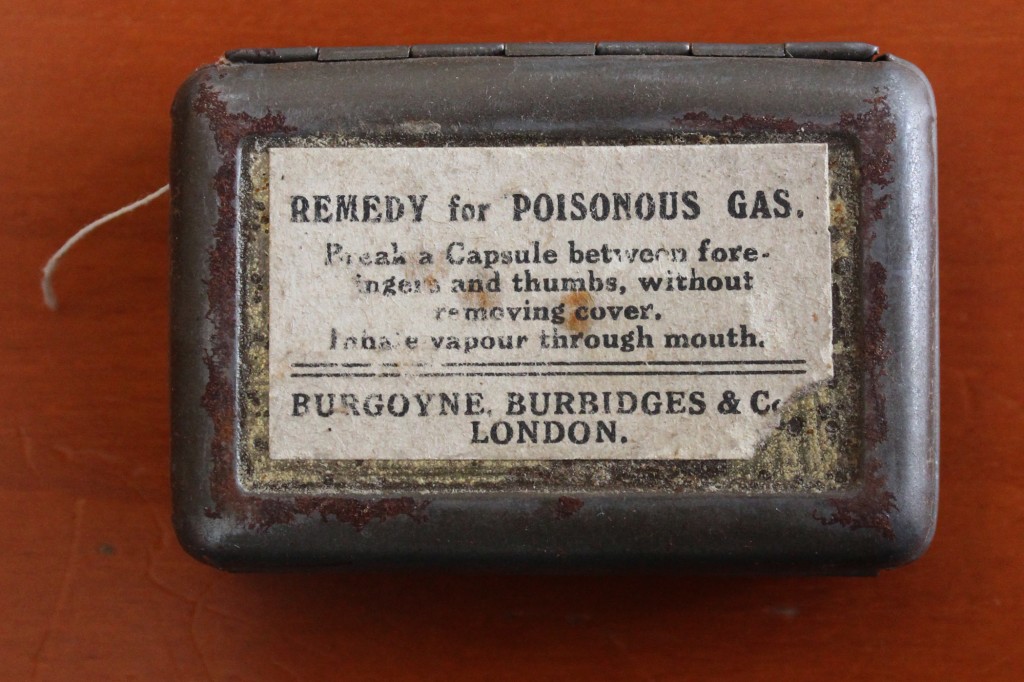

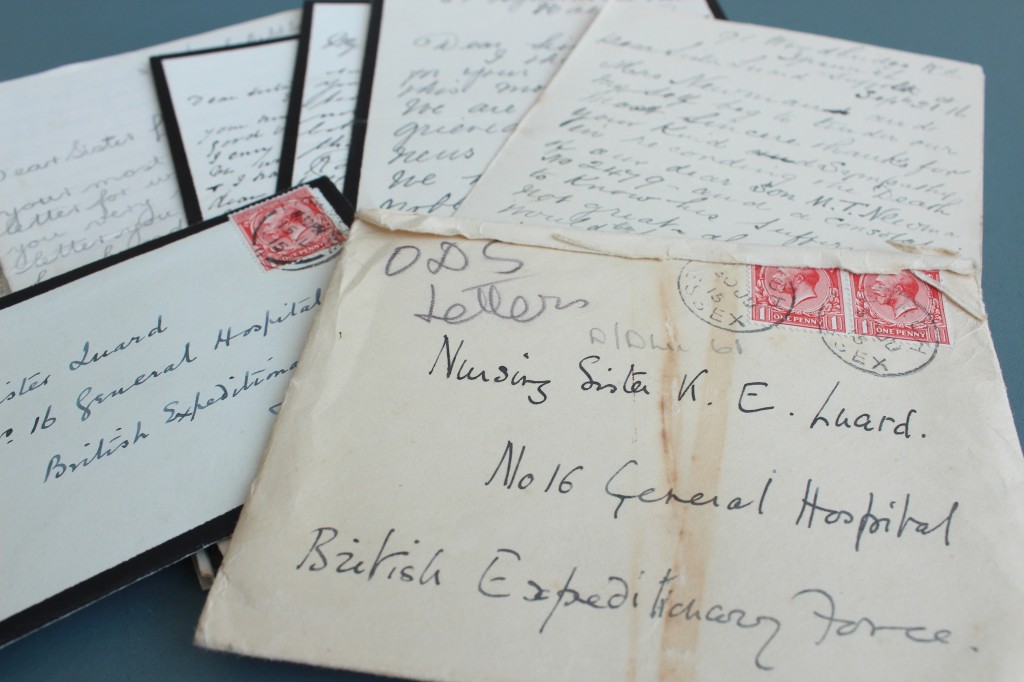

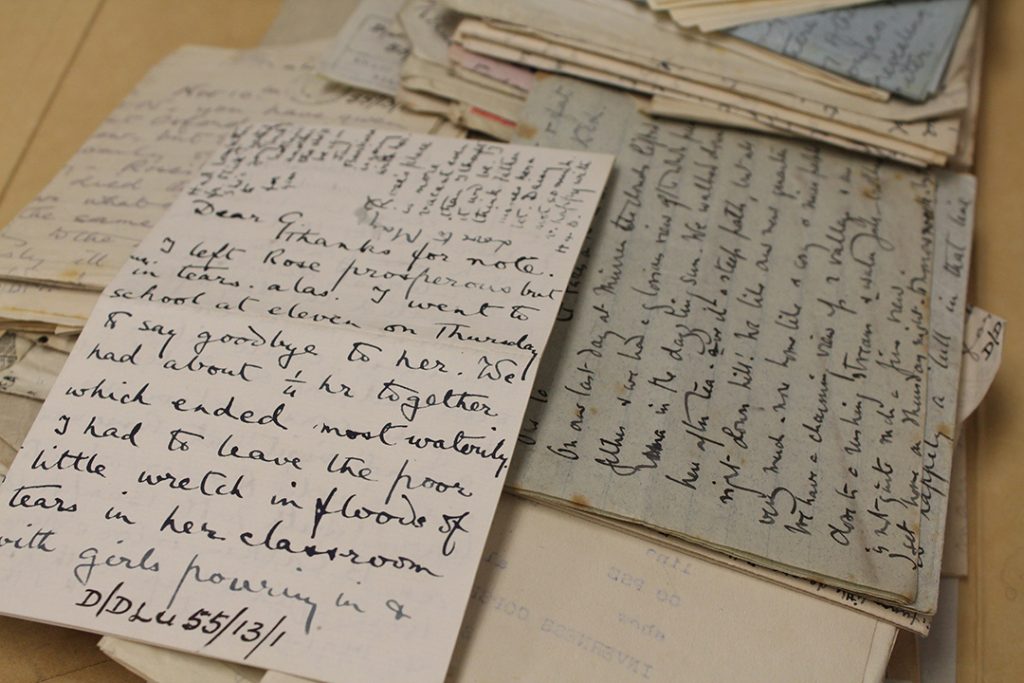

Some of Kate Luard’s letters sent to her family during her First World War service

From early March until early June 1917 Kate was with No. 32 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) in Warlencourt, in between Bapaume and Beaumont-Hamel. Her early letters from there describe the business of getting the CCS ready to go, in preparation for what would become the Battle of Arras. The construction of huts and tents took place in the snow and within range of the German guns. On Sunday 4th March she wrote of her first night there:

We had a lively night last night. We were cosily tucked up in bed with dozens of blankets, and our oil stoves burning in our canvas huts and I’d just put my lamp out, when big enemy shells came whizzing overhead from two directions. They burst a long way past us, but made a tremendous noise being fired (from a big naval gun they run up close to their line), and loud screams overhead. Our 9.2s and 12-inch in the wood here kept it up all night with lions’ roars. (Sunday 4th March 1917, UW)

In her role as sister in charge, Kate was not only responsible for organising the nursing staff and orderlies, but also for running the Mess and keeping everyone fed:

Feeding them is going to weigh heavily no my chest. It is one person’s job to run a Mess at the Back of Beyond, and I have this Hospital (700 beds) to run for night and day, with the peculiar difficulties of a new-born unfinished Camp, and emergency work. For the Mess you settle a rice putting, but there is no rice, and the cows have anthrax, so there’s no fresh milk, and the Canteen has run out of Ideal milk. Well, have a jam tart; lots of jam in the British Army, but no flour, no suet, no tinned fruits, no eggs, no beans or dried peas, not one potato each. But there is bacon, ration bread and tinned butter (when you can get it), jam, marmalade sometimes, cheese, stew, Army biscuits, tea, some sugar, and sometimes mustard, and sometimes oatmeal and cornflour. Also we have only 1½ lbs of coal per person per day, so when that is used up you have to go and look for wood, to cook your dinner and boil your water. Everyone is ravenous in this high air and outdoor life, and so long as there’s enough of it, you can eat anything. None of them I hope will grumble if we can work up the true Active Service spirit, but it is an anxiety. (Monday 12 March 1917, UW).

Once the hospital was ready to go but the fighting not yet begun, Kate and two other nurses took the opportunity to explore the surrounding areas:

Then you come to what was Gommécourt. It must have been, when it existed, full of orchards, and half in and half out of a wood. Now there is one wall of one house left. The wood and the orchards are blackened spikes sticking up out of what looks now like a mad confusion of deep trenches and deep dug-outs battered to bits. We went with an electric torch down two staircases of one and stepped into a pond at the bottom. Some are dry and clean and have the beds still in them. You step over unexploded shells, bombs and grenades of every description – and we saw one aerial torpedo – an ugly brute. I picked up a nose-cap; and the sapper who was with us said hastily, ‘That’s no good,’ and snatched it out of my hand and threw it out of sight; it still had the detonator in it. Then he picked one up without its detonator and gave it to me… Here you get to see the culmination of destruction for which all civilised nations are still straining all their resources. Isn’t it hopelessly mad? (Friday 23 March 1917, UW)

(Q 4915) Branchless trees and shattered house. Gommecourt, March 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205237124

The Battle of Arras began on Easter Monday, 9th April 1917. The following day Kate wrote:

The 3rd Army went over the top yesterday… all is splendid, but here are horrors all day and all night… All are doing 16 hours on and 8 off and some of us 18 on and 6 off… Stretchers on the floor are back-breaking work, and one’s feet give out after a certain time, but as long as one’s head and nerves hold out, nothing else matters and we are all very fit… The wards are like battlefields, with battered wrecks in every bed and on stretchers between the beds and down the middles… The Theatre teams have done 70 operations in the 24 hours. (Tuesday 10 April, UW)

By 25th July 1917 Kate and No. 32 CCS had moved on to Brandhoek, to specialise in treating severe abdominal wounds. They were stationed close behind the lines at what would become the 3rd Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). Kate was in charge of 40 nurses and almost 100 nursing orderlies.

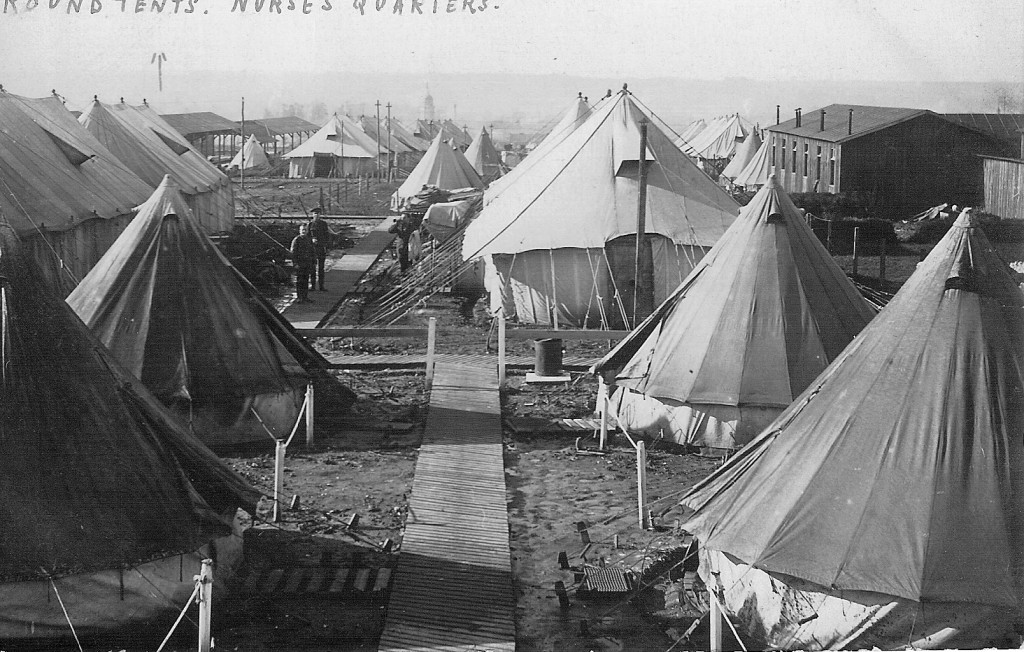

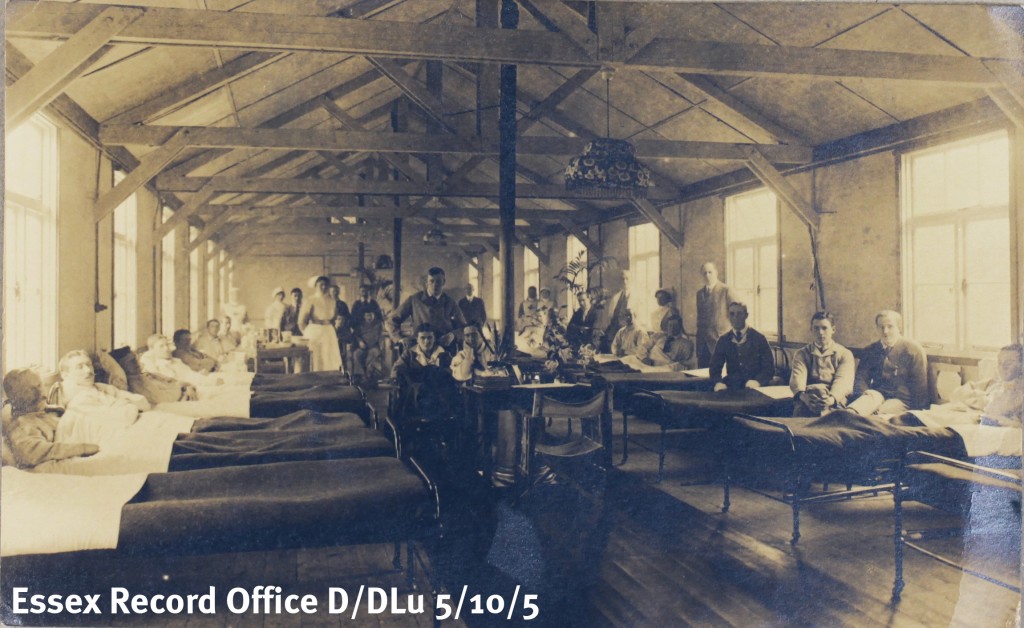

This venture so close to the Line is of the nature of an experiment in life-saving, to reduce the mortality rate from abdominal and chest wounds. Hence this Advanced Abdominal Centre, to which all abdominal and chest wounds are taken from a large attacking area, instead of going on with the rest to the C.C.S.’s six miles back. We are entirely under Canvas, with huge marquees for Wards, except the Theatre which is a long hut. The Wards are both sides of a long, wide central walk of duckboards. (Friday 27 July, UW)

The Interior of a Hospital Tent (Art.IWM ART 1611) Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23728

Everything has been going at full pitch – with the 12 Teams in Theatre only breaking off for hasty meals – the Dressing Hut, the Preparation Ward and Resuscitation and the four huge Acute Wards, which fill up from the Theatre; the Officers’ Ward, the Moribund and German Ward. Soon after 10 o’clock this morning he [Fritz] began putting over high explosives. Everyone had to put on tin hats and carry on. They burst on two sides of us, not 50 yards away – no direct hits on to us but streams of hot shrapnel. …. they came over everywhere, even through our Canvas Huts in our quarters. Luckily we were so frantically busy. It doesn’t look as if we should ever sleep again. Of course, a good many die, but a great many seem to be going to do. We get them one hour after injury, which is our ‘raison d’être’ for being here. It is pouring rain, alas, and they are brought in sopping. (July 31st, 11pm)

Stretcher bearers at Passchendaele (Imperial War Museums)

It has been a pretty frightful day – 44 funerals yesterday and about as many to-day. After 24 hours of peace the battle seems to have broken out again; the din is terrific. (Wednesday, August 1st, UW)

Crowds of letters from mothers and wives who’ve only just heard from the W.O. [War Office] and had no letter from me, are pouring in, and have to be answered. I’ve managed to write 200 so far, but there are 466. (Monday, September 3rd, UW)

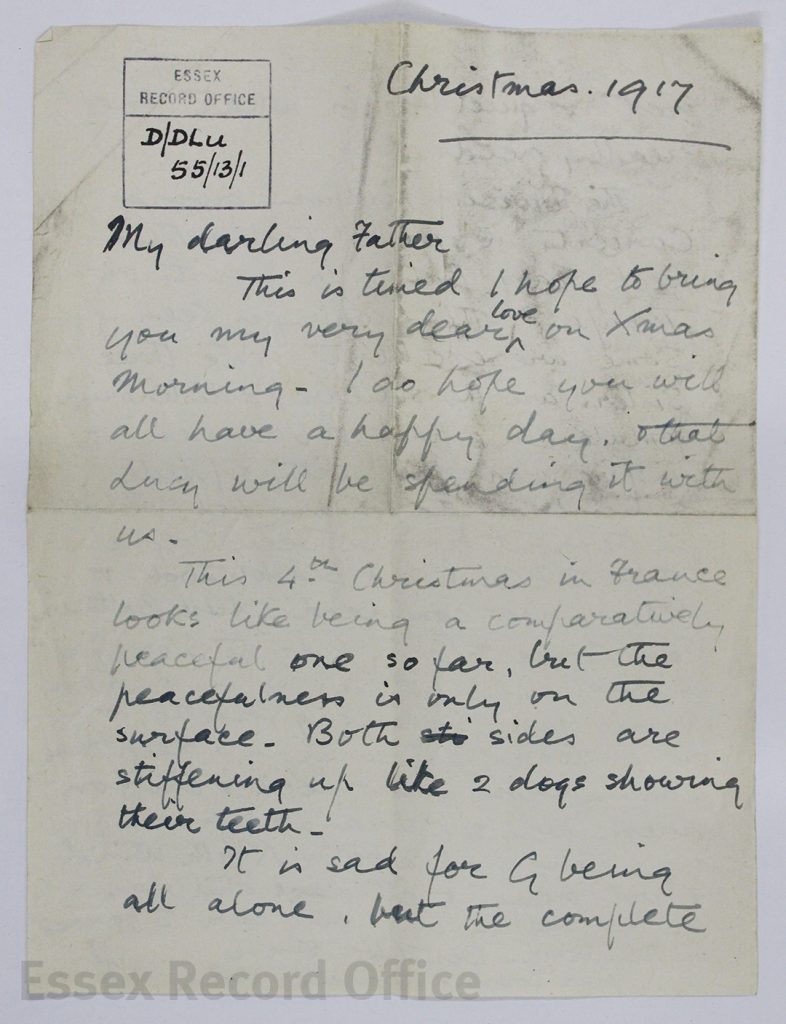

On 5 September Kate was allowed a spell of leave and she returned to England for a couple of weeks, returning to France at the end of September. She spent the remainder of the year with two other Casualty Clearing Stations – No. 37 at Godeswaersvelde and then No.54 CCS at Merville before rejoining No.32 CCS at Marchelepot in early 1918. At Christmas, she wrote home to her father:

My darling father,

This is timed I hope to bring you my very dear love on Xmas Morning – I do hope you will all have a happy day…

This 4th Christmas in France looks like being a comparatively peaceful one so far, but the peacefulness is only on the surface. Both sides are stiffening up like two dogs showing their teeth…

The Division is busy giving concerts in our big theatre this week. Each Battalion has its own Troupe, and the rivalry is keen. Some are excellent. We Three Sisters are the solitary and distinguished females in a pack of 600 men and inspire occasional witty & polite sallies from the Performers. We sit in the front row between Colonels of the 3 DG’ s and 2nd Black Watch & others, now commanding Welsh Battalions. Each concert party has its star “Girl” marvellously got up as in a London Music Hall. Some sing falsetto & some roar their songs in a deep bass coming from a low neck & chiffon dress, lovely silk stockings & high heels!

We’ve had a bitter North Wind & frost today & all have chilblains but not badly. Still only our 3 heroes in the Ward.

Best love to all

Your loving daughter

KEL [Kate Evelyn Luard]

(ERO ref. D/DLu 55/13/1, included in postscript of new edition of Unknown Warriors)

There were 11 more months of the war in store, and Kate remained on the Western Front to the end. You can read more of her letters in Unknown Warriors: the letters of Kate Luard RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918.

There were 11 more months of the war in store, and Kate remained on the Western Front to the end. You can read more of her letters in Unknown Warriors: the letters of Kate Luard RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918.

________________________________________

Locations mentioned in this blog post where Kate’s letters were sent from (click each marker for more information):