In our eleventh and penultimate post from our Chelmsford Then and Now project, Ashleigh Hudson explains how during her research project we compared historic photographs of Chelmsford High Street with today’s streetscape.

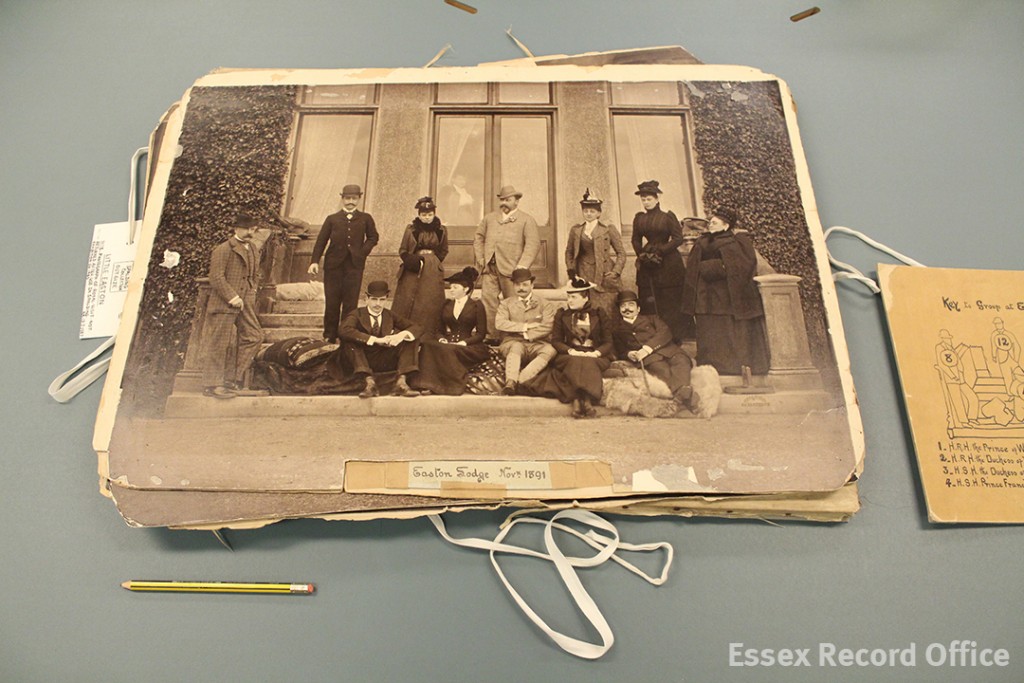

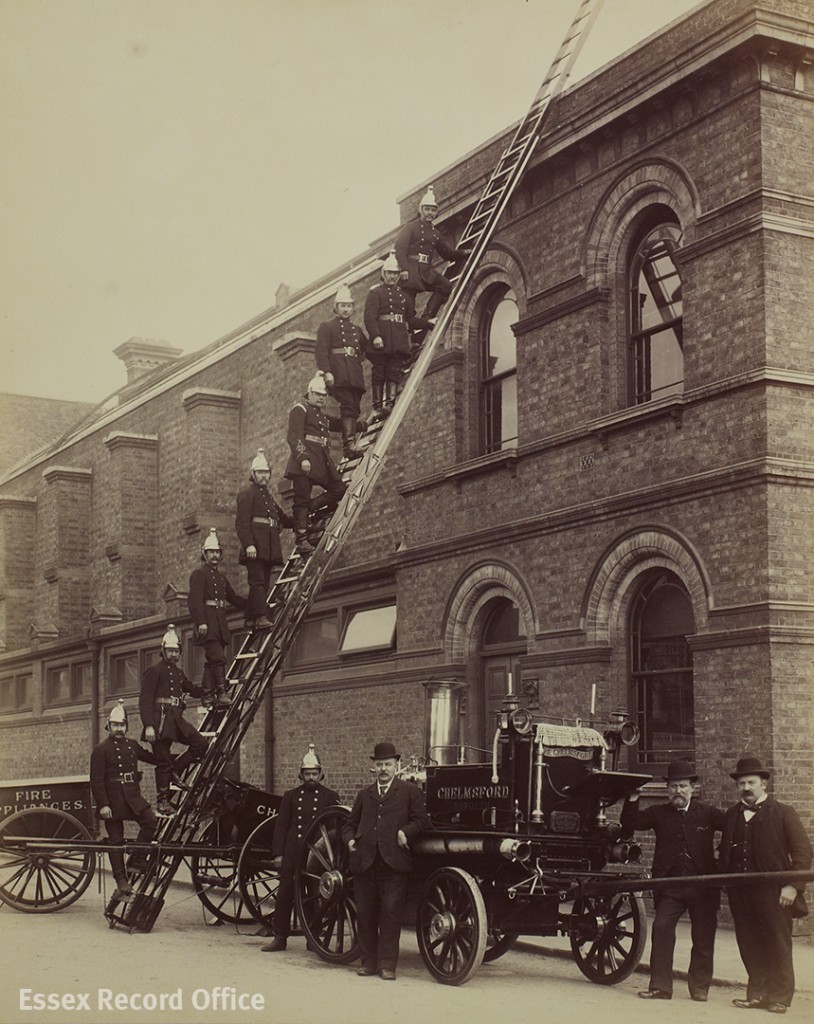

Chelmsford is often (we think mistakenly!) viewed as having little in the way of historic character. We would argue that there are, in fact, as many examples of continuity as there are of change, and the key is to know where to look. One of the invaluable resources used during this project is the Spalding photographic collection of some 7,000 images. The Spalding family of photographers were based in Chelmsford High Street from the 1860s until the 1940s, and recorded how the street has changed over time.

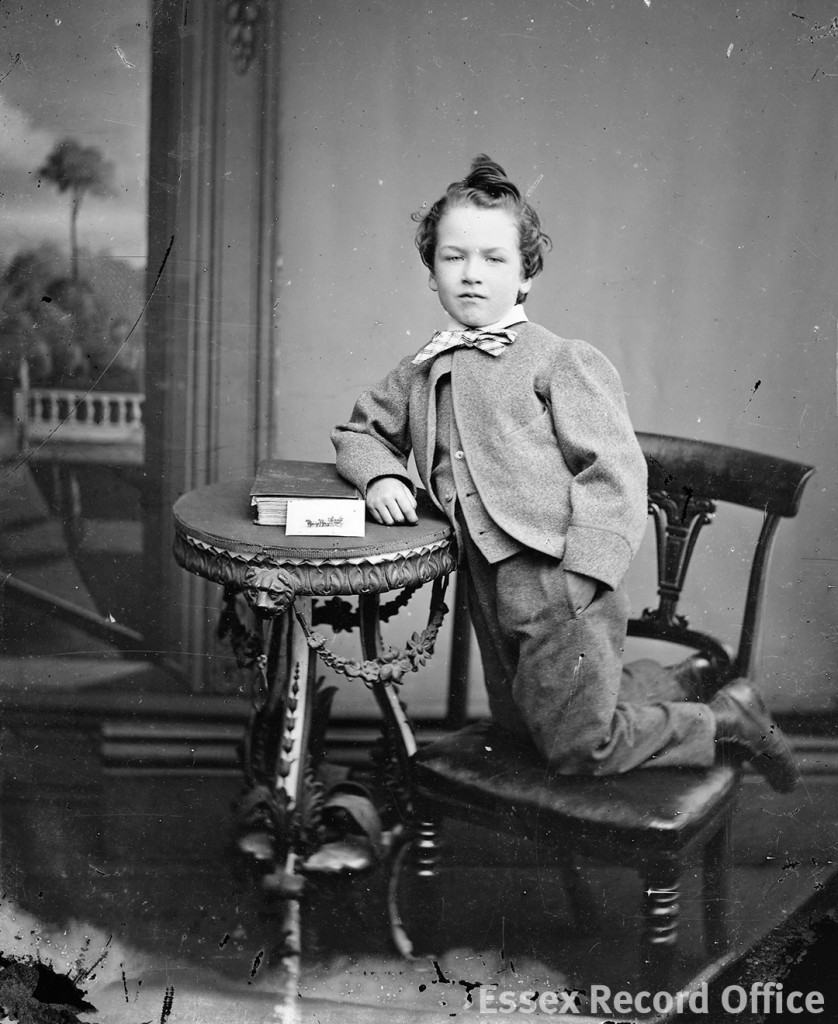

Fred Spalding senior was a self-taught photographer who set up the family business in Tindal Street in the mid-19th century. His young son, also called Fred, took a keen interest in his father’s business and quickly picked up the family trade. Several years later, an adult Fred relocated the thriving business to the site of 4-5 High Street (the current site of NatWest), where he established himself as the town’s ‘go-to’ photographer. The Spalding family captured Chelmsford through time, and their legacy endures through their magnificent collection of images. You can read more about Fred Spalding and the Spalding shop here.

We have done our best to recreate some of the Spaldings’ classic shots of the High Street, taking a set of prints out with us and dodging showers to do replicate the original pictures as closely as we could.

A quick comparison of some of the images revealed a high level of continuity across the upper half of most of the buildings. While the various owners and occupiers have changed over time, many of the architectural details have endured.

The same building today. Beneath the layers of cream and pale blue paint, the upper exterior of NatWest is very much the same as when the building was occupied by Spalding.

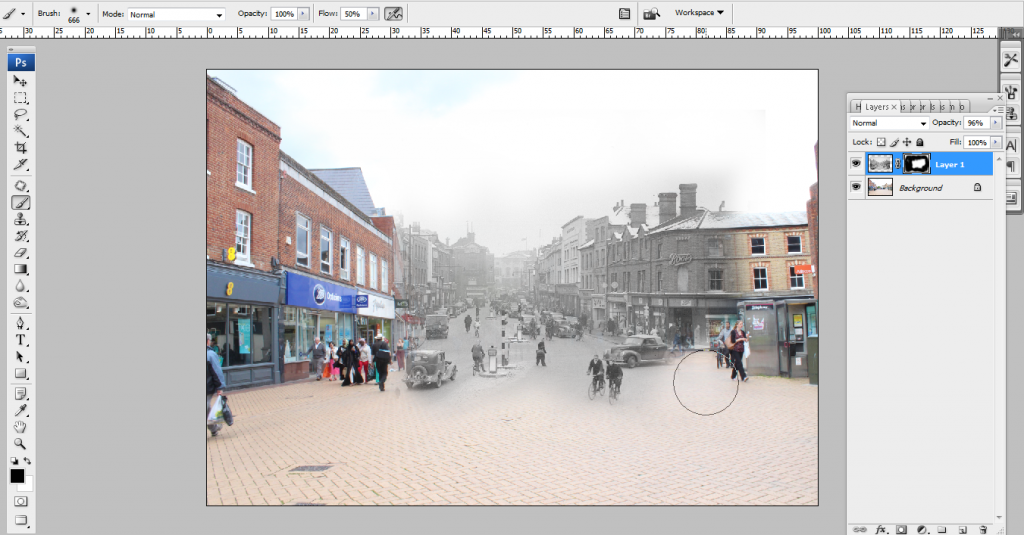

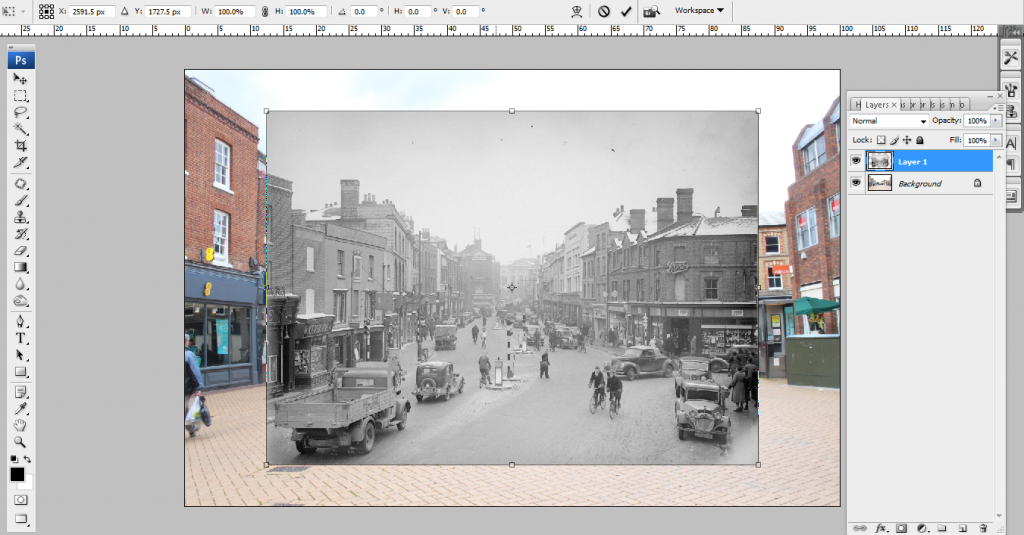

Armed with our fresh images, the fun could really being. Using Photoshop, we layered the old photographs on top of our new ones, blending the two images together:

The Spalding image is layered over the top of the current image. The image is resized and repositioned to fit the intended space

A finished example of this process. The edited image stretches down the high street, from the present day to the past.

In some instances, such as with Jamie’s Trattoria/Barclays Bank (no.2 High Street), the level of continuity is striking.

In contrast, areas where entire stretches of the High Street were demolished and rebuilt, such as the sites of Paperchase and M&S (61-62 High Street), the edited images revealed how parts of the High Street are completely unrecognisable.

The west side of the high street featuring the Queen’s Head in the centre and a building that would later form part of the future site of Marks and Spencer’s. These buildings have since been demolished and the site redeveloped, which is why the images do not match up smoothly.Ch

You can see the final results of our image blending on our Historypin page, or you can visit the Searchroom to explore the full extent of the Spalding photographic collection.