Martin Astell, Sound Archivist

The Essex Sound and Video Archive has fully equipped studios for digitising all kinds of sound recording media – from open reel tapes to digital DAT tapes; from shellac discs to vinyl discs to mini-discs. The equipment is used for making high quality digital copies of the many recordings held at the Essex Record Office, but we are also able to do the same for other people’s recordings too.

We recently had the pleasure of digitising an interesting recording for the London Metropolitan Archives. It is a 78rpm shellac disc containing a speech made by Viscount Wakefield of Hythe on the occasion of him being made a freeman of the City of London in July 1935. As well as being able to hear a unique voice from the past – one of the constant joys of the Sound Archivist – this was an interesting disc to transfer for a couple of other reasons.

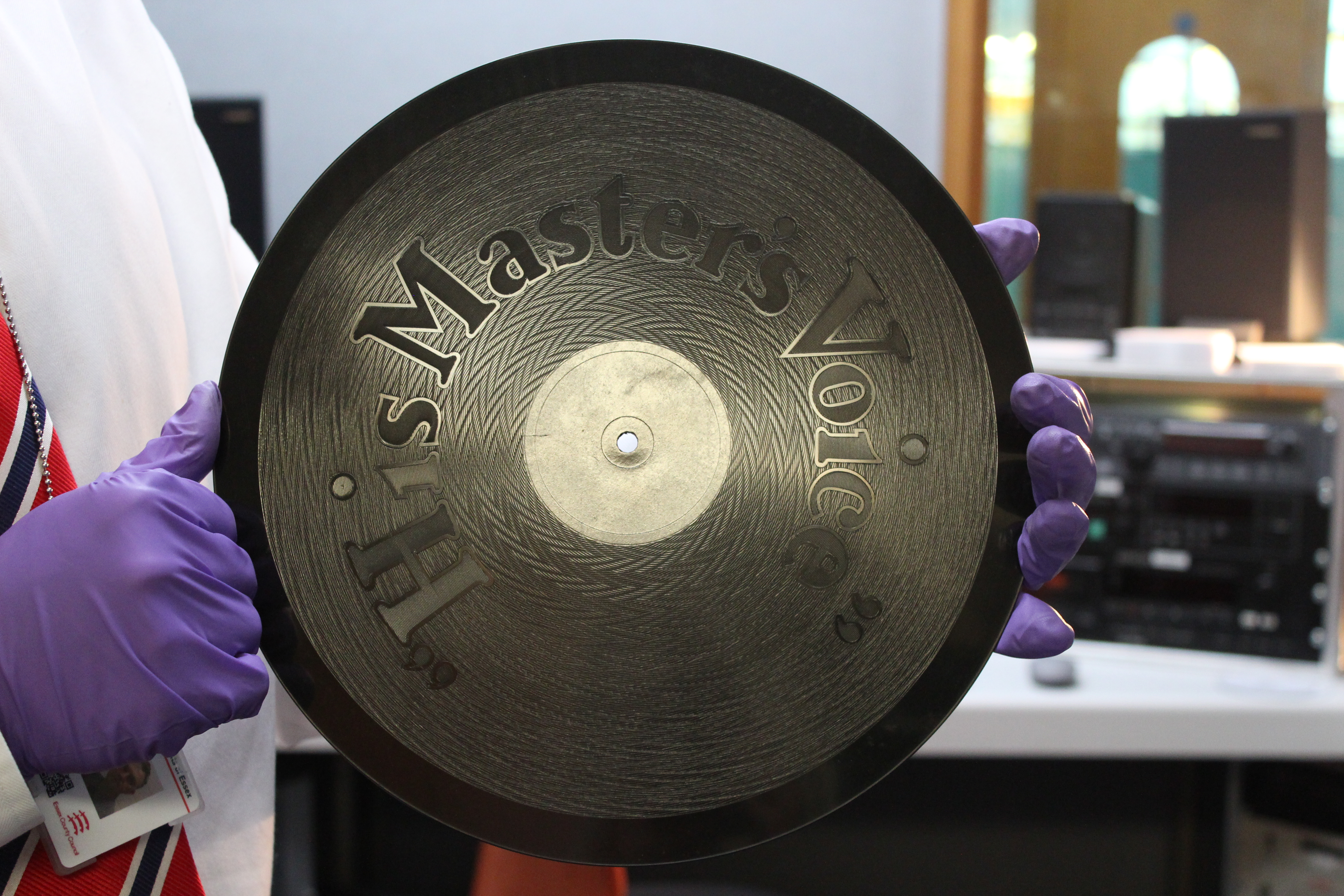

Because this was a ‘private’ recording, rather than one made for general release, the disc has no B-side. Instead this side is decorated with rather beautiful patterns and the “His Master’s Voice” legend.

The second thing I noticed on examining the disc before the digitisation transfer was that it had become somewhat warped. This is not necessarily a problem as the groove remains intact. However, because the disc is travelling quite quickly on the turntable – at 78rpm this means a complete rotation in less than a second – a warped disc can cause the stylus to jump out of the groove, not only spoiling the recording but potentially damaging the surface of the disc as it lands.

To avoid this risk I began by playing the disc at a much slower speed with the intention of correcting the sound digitally if it proved necessary. The speed was increased gradually to ensure the stylus was safely held in the groove at all times and, in the event, I was able to complete the digital transfer at the correct speed.

The disc was also cleaned on a VPI record cleaning machine. As the disc spins, the cleaning fluid is carefully placed on the recording surface avoiding the paper label in the centre of the disc. The fluid is worked into the groove with the brush and then removed using the vacuum. The process is then repeated using distilled water.

The London Metropolitan Archives now have a high quality digital copy of the speech which can be preserved for the future and, being digital, is much easier to make available for researchers.

If you have sound recordings which you would like digitised, give me a call at the Essex Record Office on 033301 32500.