To celebrate #WorldBeeDay on 20th May, we take a look at the the Essex Beekeepers’ Association archive held at the Essex Record Office.

Before the invention of the modern wooden beehive in the mid-nineteenth century, bees were often housed in bee boles – a row of recesses each large enough to hold a coiled-straw hive called a skep. These bee boles were typically built in to south-facing garden walls.

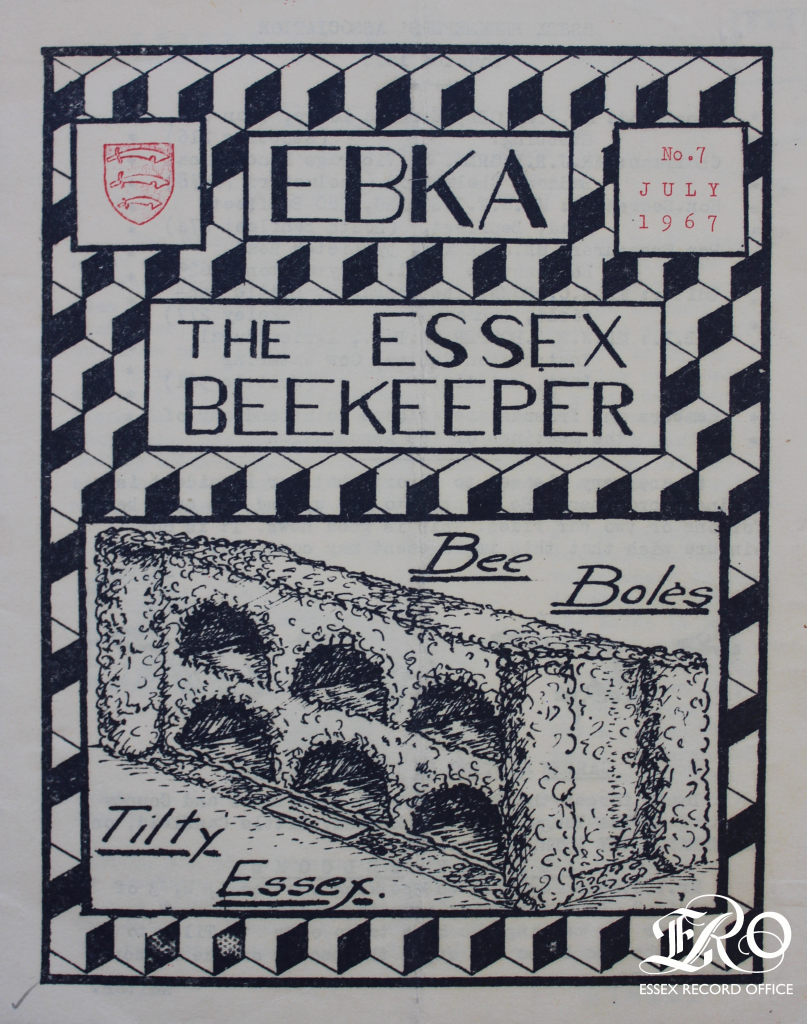

In 1967, the Epping Forest Division of the Essex Beekeepers’ Association repaired the bee bole at Tilty, near Dunmow in Essex. Their Annual Report for the year includes an account of the work carried out by their volunteer construction team made up of a retired schoolmaster, a draughtsman/artist, a joiner/carpenter, a police officer, and a postman. The bee bole is flint with brick arch supports and the top storey of the structure was almost entirely rebuilt by the team. They left a time capsule inside the bee bole containing some monthly circulars published by the Division and some mead with a note reading: “We believe that the structure was part of a Priory known to have existed here before the dissolution of the monasteries, and we hope that it will be as long again before this honey jar and contents are discovered”. The Priory mentioned is the Cistercian Abbey of St Mary at Tilty. The nearby Church of St Mary, originally the Abbey chapel, has flint and stone chequerwork below the east window. The front cover of the Annual Report (pictured below) is beautifully illustrated by Mr H. C. Moss and depicts the repaired bee bole.

The annual report is held at the ERO as part of the Essex Beekeepers’ Association archive. The collection includes their first minute book covering 1880-1910 containing the minutes of their inaugural meeting at 90 High Street, Chelmsford on 14 July 1880 and a label for a jar of honey. The label was selected on 12 April 1897 when it was agreed that 20,000 should be printed by Mr A D Woodley at a cost of £5.

You may also be interested in a previous blog on the changing pattern of land usage and the historic value of meadows to the Essex landscape which is available to read here.