Julie Miller, a masters student from University of Essex, has taken up a research placement at the Essex Record Office, conducting an exploration into the story of John Farmer and his adventures, particularly in pre-revolutionary America, and has been jointly funded by the Friends of Historic Essex and University of Essex. Julie will be publishing a series of updates from the 12-week project

This time we are looking at the most exotic leg of John Farmer’s first American journey when he toured the islands of the Caribbean.

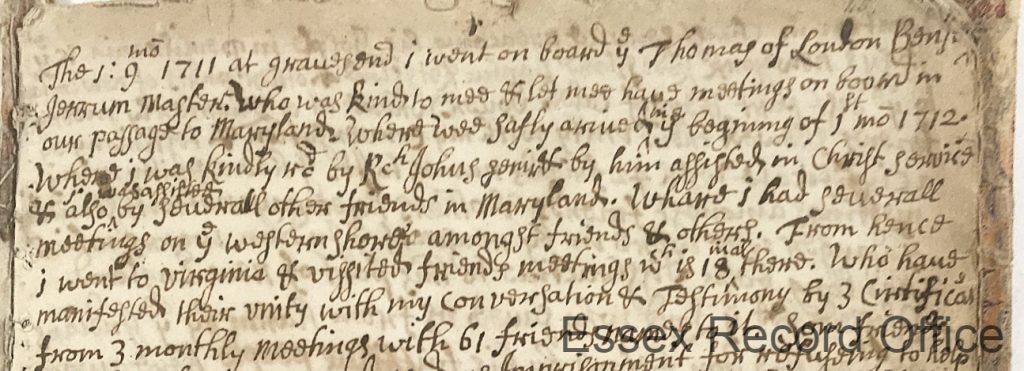

In the course of nearly two years Farmer had travelled through Pennsylvania, the Jerseys, to New York, Nantucket Island, Long Island, Boston, Rhode Island, and Virginia, holding meetings wherever and whenever he could, bringing his Quaker Testimony and gathering Certificates of Unity from the various Friends’ Meetings he visited along the way.

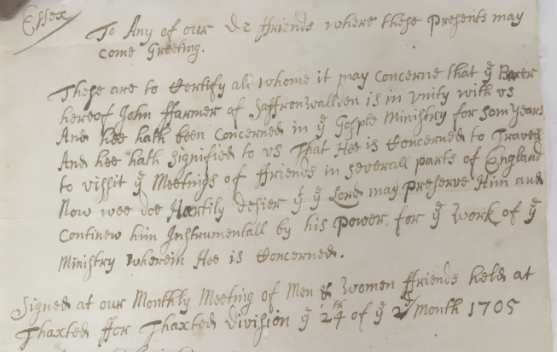

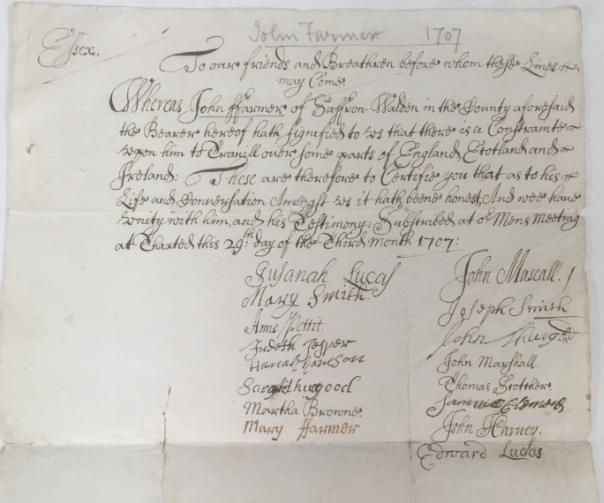

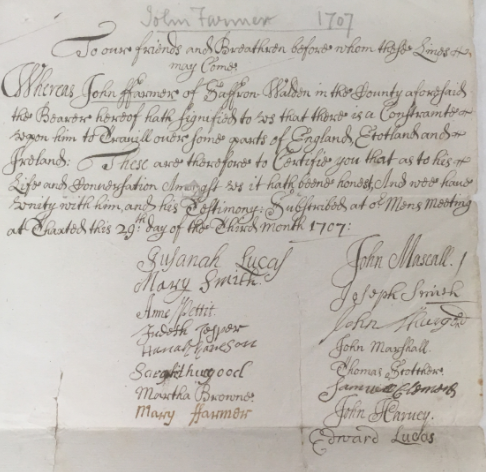

Certificates were important documents as Quakers travelled only with the agreement of their fellow Friends, and their home meeting would issue a Certificate confirming their unity with the testimony that individual gave, and in return meetings who received that testimony would give a certificate confirming their satisfaction.

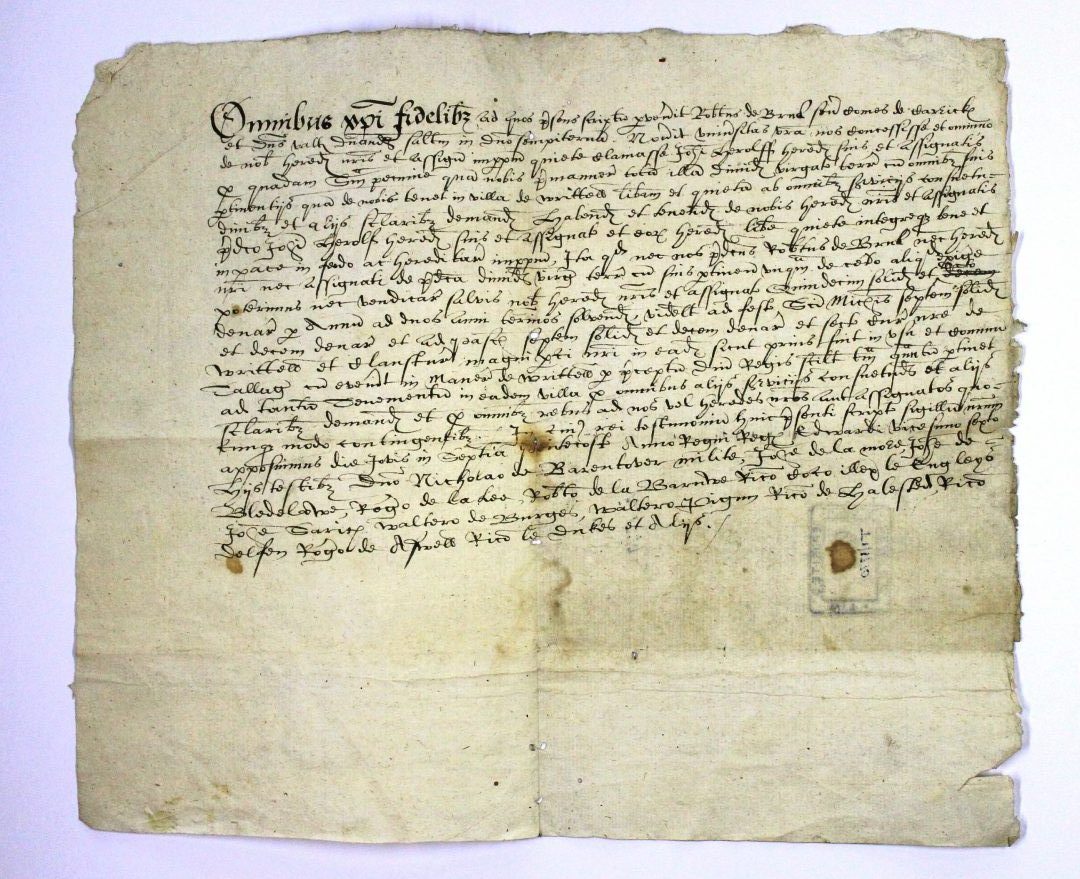

An example here is from Thaxted, held here at the Essex Record Office, confirming their approval for John Farmer to travel in 1707, and their unity with him and his testimony. Note it is signed by his wife Mary Farmer as well as a number of other Quakers.[i]

Arriving in Philadelphia at the end of October 1713 John Farmer reviewed his progress so far:

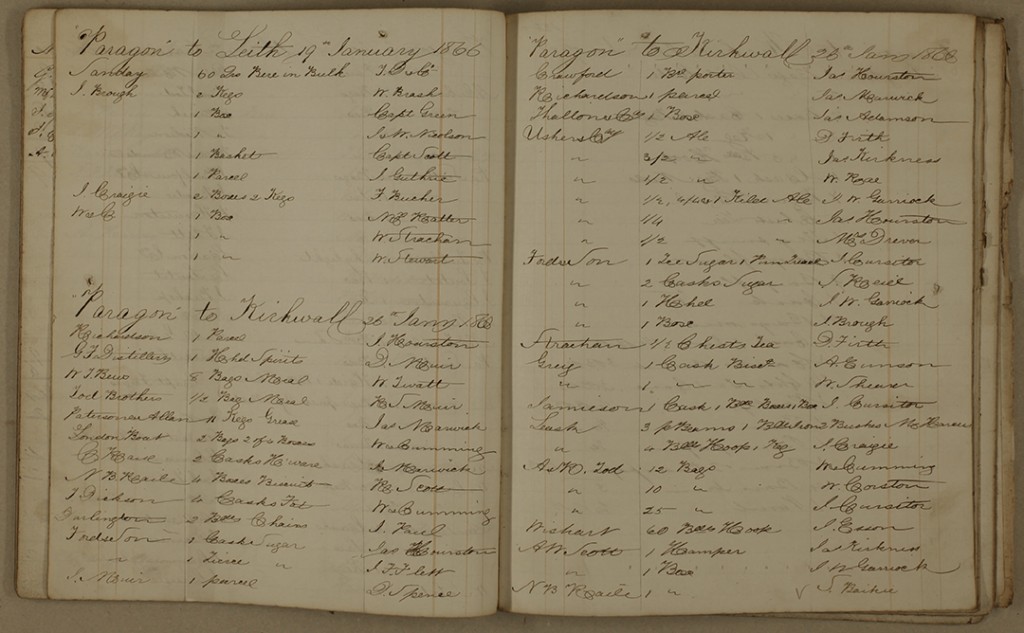

“I cast up my account of the miles I had traveled in North America & found it to bee 5607 miles. Friends of Phyladelpha & Samuel Harrison merchant a friend of London beeing there & having there a ship bound to Barbados were very kinde to mee & John Oxly (a minister of Phyladelpha) who went with mee: som in laying in Provishon for us & Samuel Harrison in giving us our passage to Barbados. Wee went on board the latter end of the 9th month 1713 [November 1713] [ii].

Wee had a pritty good voyage & had som meetings on board in our passage to Barbados where wee arrived the 5th of the 11th month 1713’ [5th January 1713/14].” [iii]

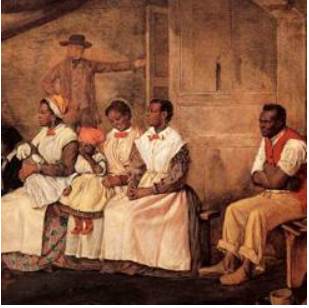

Quakers had been appearing in the Caribbean since the early 1650s, some coming as transported slaves from Britain, punished for being Quakers but others seeking the religious and career freedoms denied in their home countries. In Britain religious dissenters were denied the option of going to university or taking up the professions, so many became businessmen, and the Caribbean colonies offered opportunities for trade, running large plantations and owning ships, as well as a greater freedom of religious expression than in Britain in the second half of the 17th Century.[iv]

The trade in cotton, sugar, coffee and tobacco required huge numbers of slave workers, many owned by Quaker families. There was a divided spirit within Quakers about the trade in human beings, and the owning of slaves. As early as 1671 the founder of Quakerism George Fox had suggested slaves should be considered indentured servants and liberated after a given period of time, perhaps 30 years, and that they should be educated in Quaker religious beliefs[v]. The difficulty this caused was that Quakers believed all men to be born equal, and therefore by bringing their slaves into the Quaker brotherhood it meant they should be considered of one blood with their white masters. This dilemma meant that there was disquiet for the next 100 years in Quaker communities as they wrestled with the issue of whether or not they should keep and trade in slaves.

Despite travelling through the slave owning states in America and the Caribbean Islands John Farmer passed no comment on the slavery situation in his 1711-14 Journal. For now he was silent on the matter. Almost inevitably, John Farmer eventually waded into this highly controversial dispute, with catastrophic results, but that is a story for another day.

John Farmer made a four-month tour of the Caribbean islands of Nevis, St Kitts (which he called Christopher’s Island as Quakers did not recognise saints), Anguilla and Antigua holding several meetings.

In Barbados he held a large meeting in ‘Brigtoun’ (Bridgetown) where he remarked that the public were very civil. In Anguilla he wrote disapprovingly that the Quaker congregation had “fell away into drunkenness and other sins which so discouraged the rest that of late they kept no meeting.” [vii]

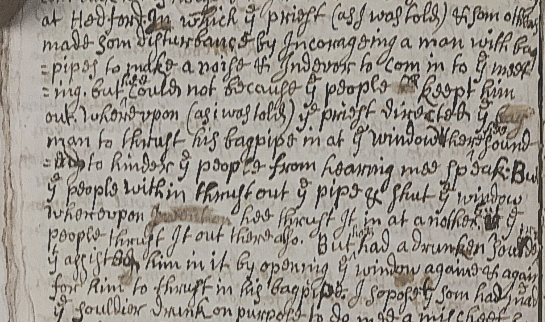

Antigua was more successful, and he held 26 meetings and stayed five weeks bearing “Testimony for God against the Divell and his rending, dividing works on this island.’ But on one occasion in Parham, Antigua, Farmer again fell afoul of the local priest who “Preached against Friends [and] some of his hearers threatened to do me a mischief if I came there away and had another meeting.” [viii]

In Charlestown on Nevis, Farmer again endured the tradition of protest by charivari (protest by rough music) something which had also happened in Ireland on a previous journey[ix], but this time with fiddles rather than Irish bagpipes and with somewhat darker consequences. John Farmer encountered a troublesome Bristol sea captain who decided to have fun at the intrepid Quaker’s expense, and paired up with an innkeeper to disrupt Farmer’s meetings by arranging for loud and continuous fiddle playing to drown out his preaching. Farmer mused in his journal on the fact that the sea captain died a few days later of a “fevor & disorder” reflecting that God’s judgement may have come down upon the disturber of his meeting, reporting with some satisfaction that “at his buriell the Church of England preacher spake against people making a mock & game of religion”.[x]

Farmer wrote in his journal that while in Barbados he received instruction from God to go home to England for a short time before going back to America. Perhaps this was a clue to the next phase of his life. He took ship for England on the Boneta of London, sailing from Antigua 24th May 1714 and he landed safely back in London where his wife and daughters were waiting for him. They then travelled on to Holland and also visited friends and family in Somerset and the south west before arriving home in Saffron Walden on 28th November 1714.

This is where the John Farmer journal finishes, but his story went on for another 10 years. A story of passionate anti-slavery campaigning that cost John Farmer very dear.

And that will be the story to be told in my next post about

John Farmer’s extraordinary life.

[i] Essex Record Office A13685 Box 47 Certificate for J Farmer to travel 29.3rd mo. 1707 (29th May 1707)

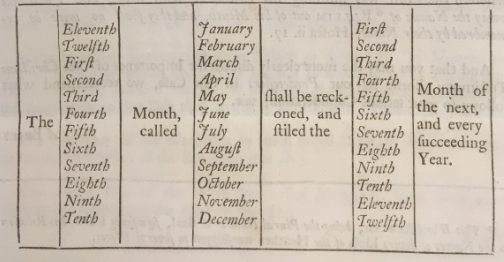

[ii] A note on the dating processes used prior to 1751: Years were counted from New Year’s Day being on March 25th, so for example 24th of March was in 1710 and March 25th was in 1711. In addition Quakers provided an extra difficulty as they refused to recognise the common names for days of the week, or months as they were associated with pagan deities or Roman emperors. So a Quaker would write a date as 1:2mo 1710 which was actually the 1st April 1710 as March was counted as the first month. In 1751 this all changed when the British government decreed the Gregorian form of calendar was to be adopted and the new year would be counted from 1st January 1752. See my previous post An Essex Quaker Goes Out into the World.

[iii] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p57

[iv][iv] For more information relating Quakers and the Slave trade see

Drake, T.E., Quakers & Slavery in America, Oxford University Press, London 1950

Rediker, M. The Fearless Benjamin Lay, 2017, Verso, London

Soderlund, J.R, Quakers & Slavery, A Divided Spirit, Princeton, 1985

[v] Drake, T.E., Quakers & Slavery in America, Oxford University Press, London 1950 pp. 6-9

[vi] Quakers in the Colonies: www.quakersintheworld.org/quakers-in-action/268

[vii] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p57

[viii] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p57

[ix] See previous post An Essex Quaker in Ireland, to understand more about protest by music.

[x] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p58