In the run up to Magna Carta: Essex Connections we take a more detailed look at the Essex connections of Geoffrey de Mandeville, one of the rebel barons.

One of the most radical things about Magna Carta was that the rebel barons chose 25 representatives to ‘observe, hold and cause to be observed, the peace and liberties which we have granted and confirmed’. King John was not trusted and the barons were to ensure that the promises made were kept by distraint if necessary. Distraint is the process by which property can be seized to pay money owed, but can also be used to ensure that an obligation is carried out. It was a well-established practice in the Middle Ages, but Magna Carta extended its use against the king by his subjects.

Among the 25 Magna Carta barons there were six with strong Essex connections – Robert FitzWalter, Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, Robert de Mountfitchet, John FitzRobert and William de Lanvallei. In addition another four – Richard de Clare, Earl of Clare and his son Gilbert de Clare and Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and his son Hugh Bigod, also held lands in the north of the county, although they were more usually associated with Suffolk and Norfolk.

Here we look at Geoffrey de Mandeville and his father, Geoffrey FitzPeter, who we mentioned in our recent post on our two documents from the reign of King John.

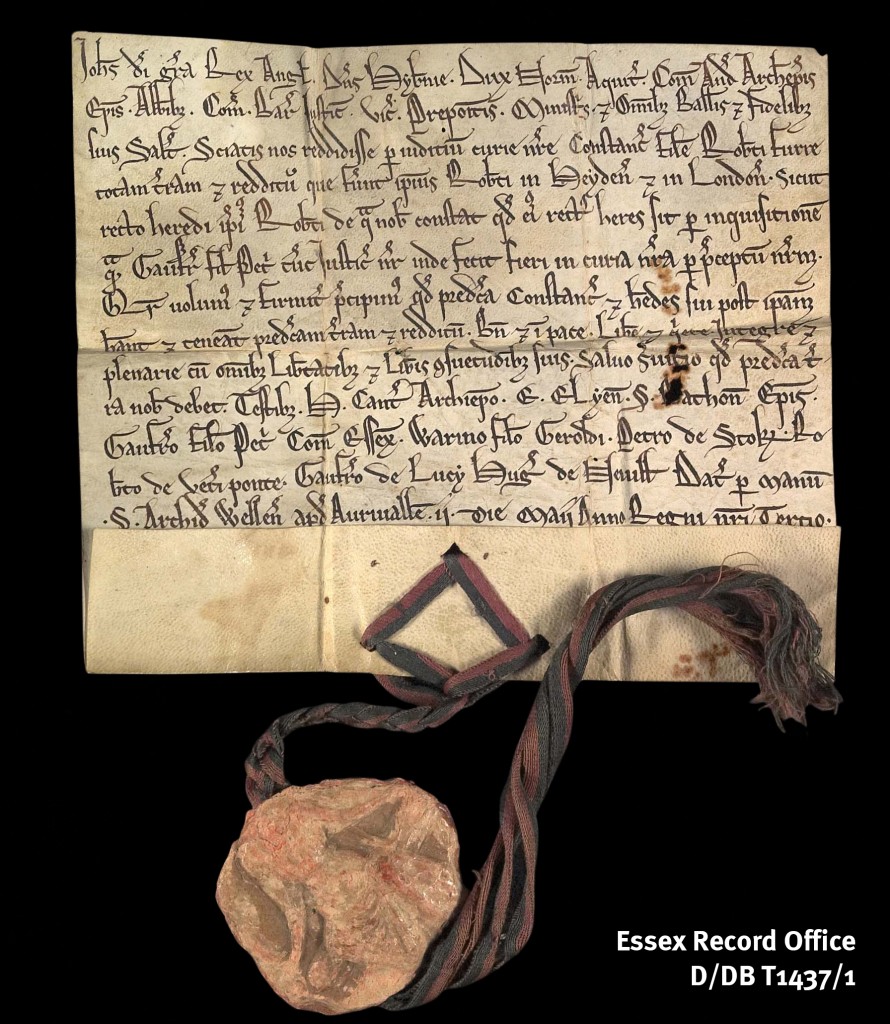

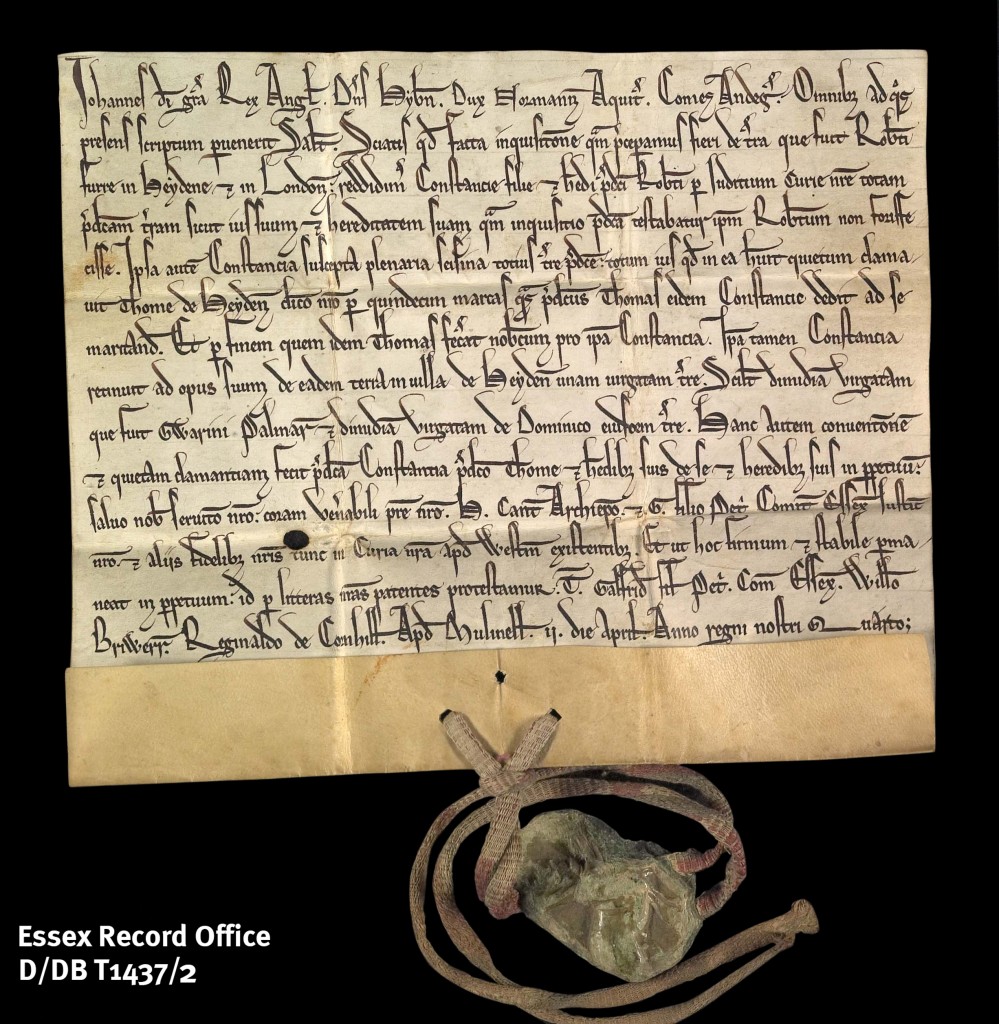

Both of the 1203 documents we have mention Geoffrey FitzPeter, who served as justiciar under both Richard the Lionheart and King John. The justiciar was the chief political and judicial officer of the king, roughly equivalent to today’s prime minister.

The justiciar was accustomed to govern the country in the king’s absence. The Essex historian Revd. Philip Morant in 1768 described FitzPeter as the ‘firmest Pillar of the realm, generous, skilful in the laws, and in money and everything else and allied to all the great men of England either in blood or friendship’.

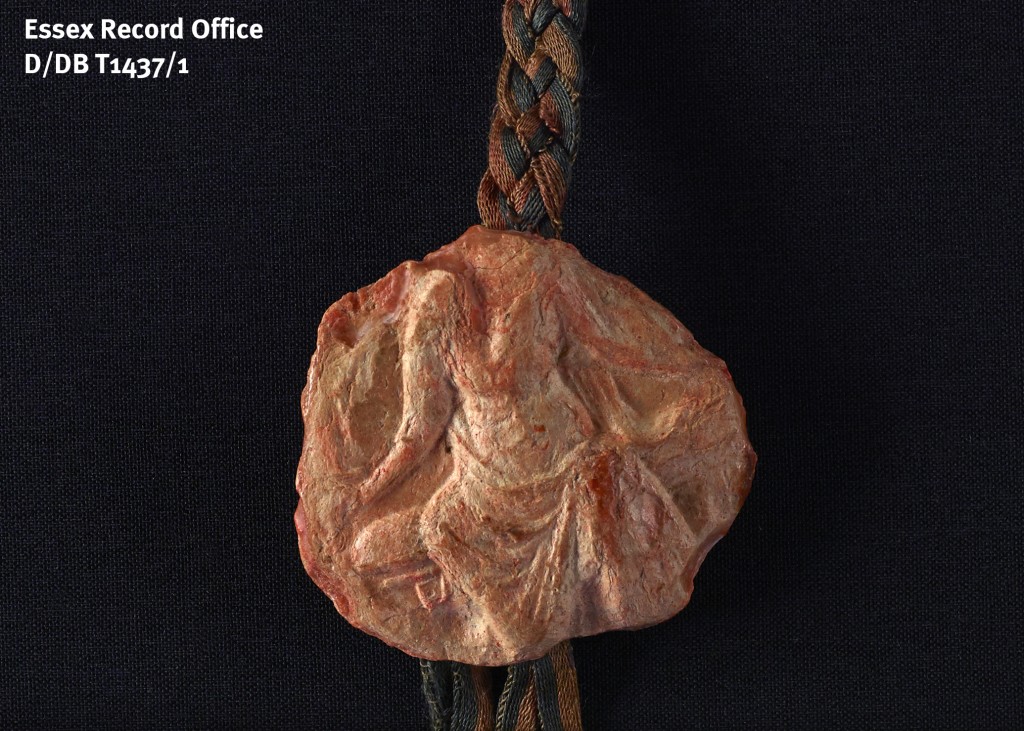

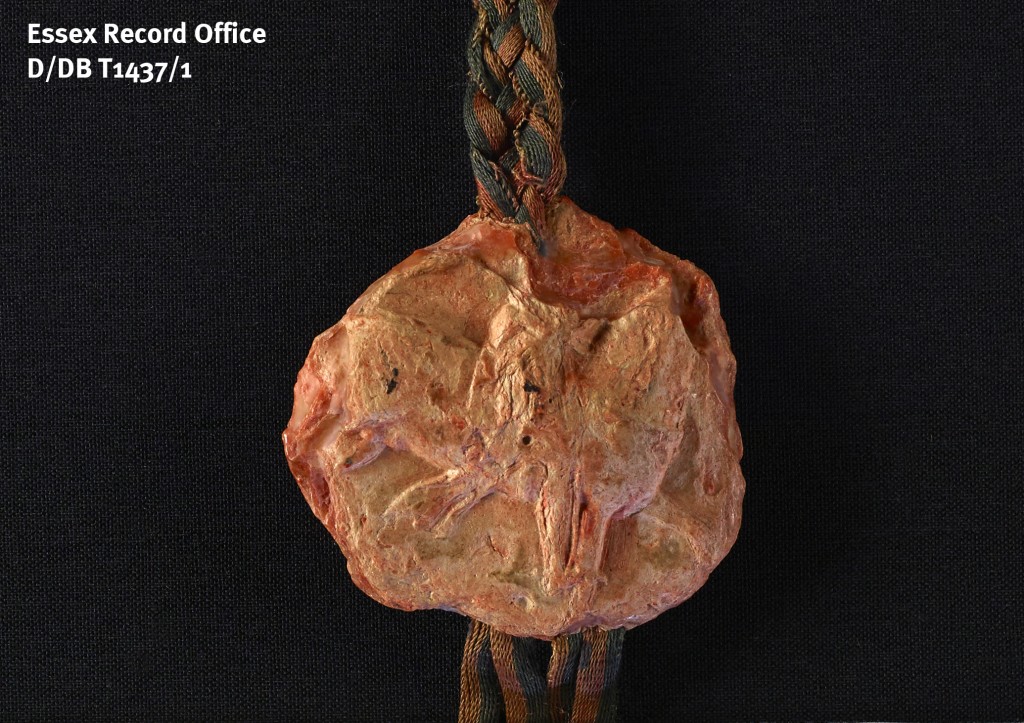

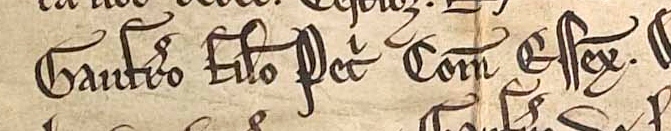

Extract from D/DB T1437/1, where Geoffrey FitzPeter is named (‘Gauf[r]i[d]o filo Pet’[ri] Com[itato] Essex’)

Geoffrey FitzPeter had married Beatrice de Say who was the great-niece of Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex. When Geoffrey de Mandeville’s youngest son William, 3rd Earl of Essex died without an heir, his extensive lands in Essex and elsewhere were disputed between two branches of the de Say family. Geoffrey FitzPeter, with his royal influence, won out, and King John appointed him Earl of Essex on his coronation day in 1213.

His sons Geoffrey and William both assumed the name de Mandeville and both succeeded him as Earl of Essex. His eldest son Geoffrey de Mandeville was one of the 25 barons appointed to ensure that King John kept to the promises made in Magna Carta.

It is not surprising to find Geoffrey de Mandeville on the rebel side in 1215. His first wife Maud was the daughter of Robert FitzWalter, another important Essex landowner and effectively the rebel leader (more on him and his daughter coming soon).

After Maud’s death, Geoffrey married Isabella, the divorced ex-wife of King John. The marriage was probably forced upon him, and John charged him a ruinous fine for the privilege.

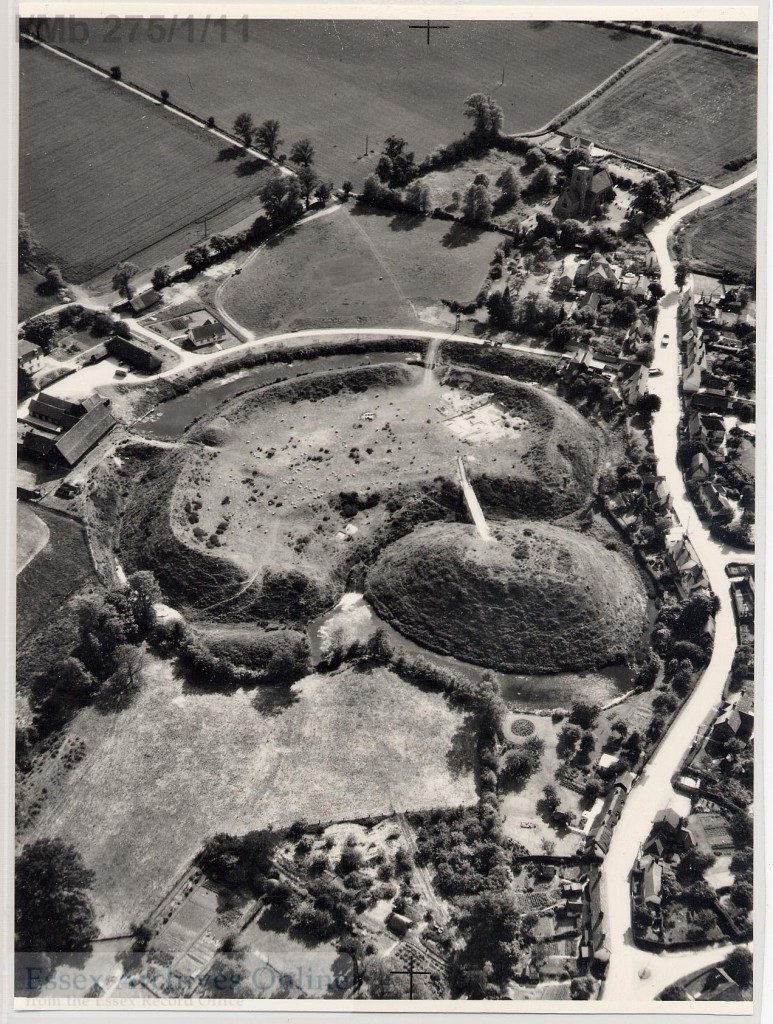

In December 1215 the de Mandeville castle at Pleshey was besieged by the royal forces. Geoffrey was killed at a tournament in February 1216 and was succeeded by his brother William, another opponent of King John, who fought royal forces in Essex in 1216.

There are more posts to come exploring the Essex connections with the Magna Carta, but in the meantime give us a ring on 033301 32500 to book for Magna Carta: Essex Connections on Saturday 23 May.

Magna Carta: Essex Connections

To explore the significance and legacy of this famous document, both nationally and for Essex, join us for talks from:

- Nicholas Vincent, Professor of Medieval History at the University of East Anglia, who has been leading a major project researching the background to Magna Carta

- Katharine Schofield, ERO Archivist, on Essex connections with Magna Carta and the impact it had on the medieval county

Saturday 23 May, 1.15pm for 1.30am-4.15pm

Tickets: £8, including tea, coffee and cake

Please book in advance on 033301 32500