In our final blog post in the run up to Magna Carta: Essex Connections on Saturday 23 May, we look at a document that is something of a post-script to our recent Magna Carta, but it is an interesting medieval document we wanted to share.

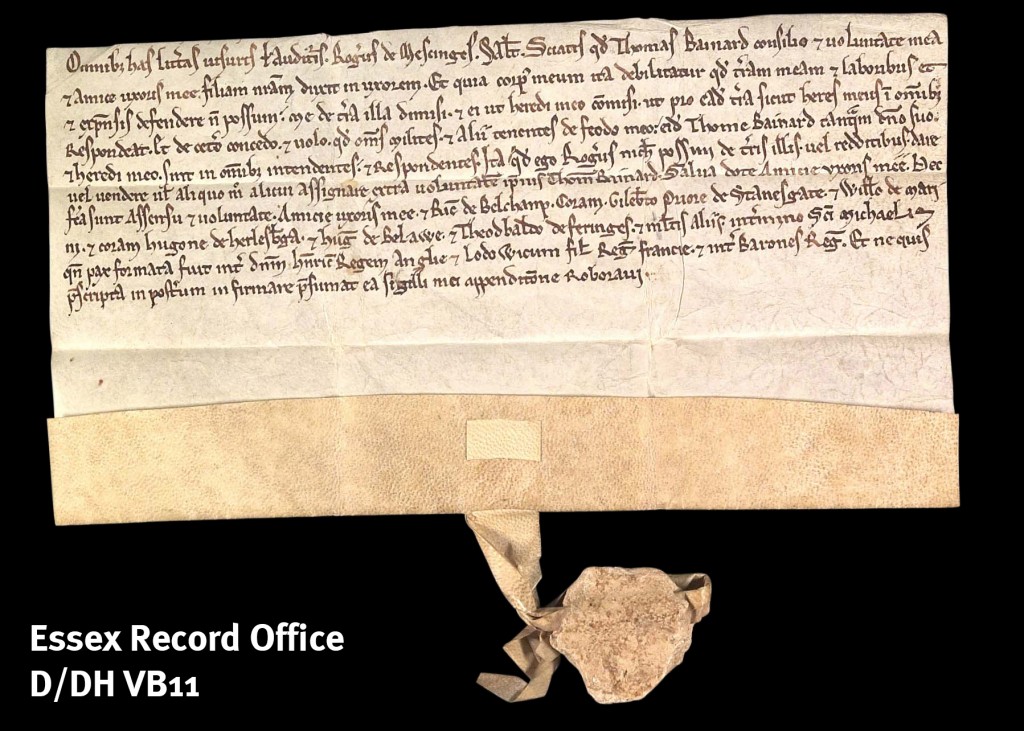

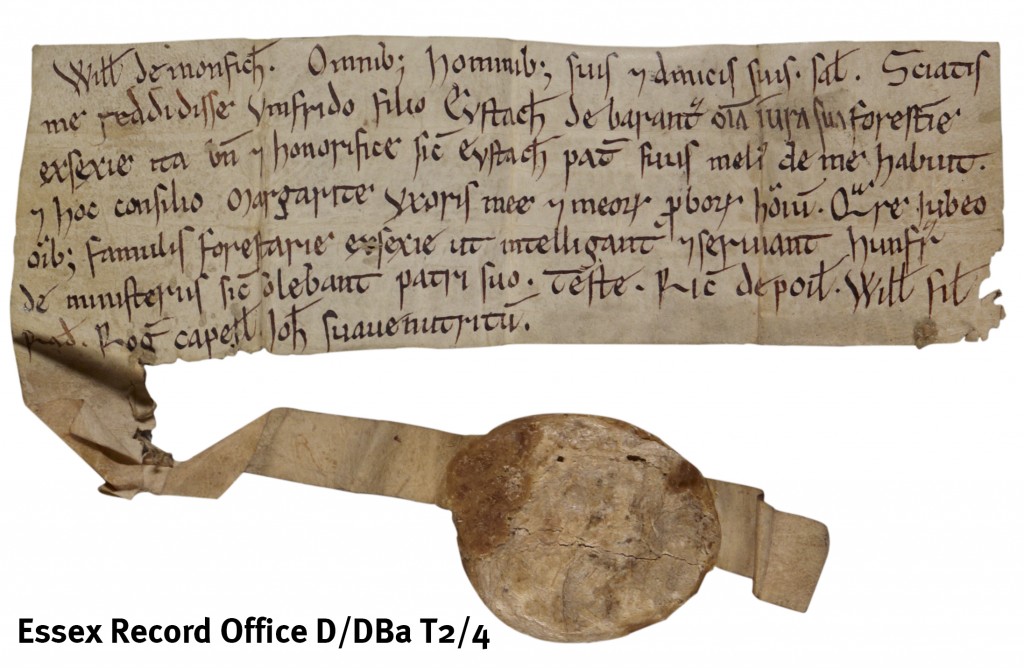

The document is a grant made by Roger de Mescinges [Messing] of all his lands, knights and other tenements of his fee to his son-in-law Thomas Bainard (D/DH VB11).

There are two key features which make it particularly interesting: first, it is possible to give this a definite date, which is unusual in medieval deeds, and second, it gives us an insight into the mindset of a landowner during the unrest following the granting of the Magna Carta in 1215.

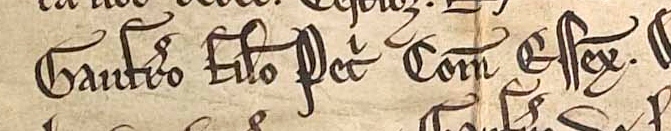

Its date can be narrowed down very precisely, because of the reference it makes to the Treaty of Lambeth, which was agreed on 11 September 1217 between the rebel barons, the new King Henry III, and Prince Louis of France, who agreed to give up his claim to the English crown.

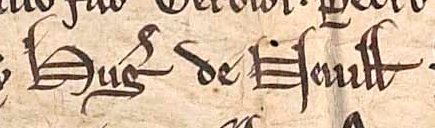

After listing the witnesses, this deed states that it was made in the time ‘when peace was made between the lord Henry, King of England and Louis son of the King of France and between the barons of the king’.

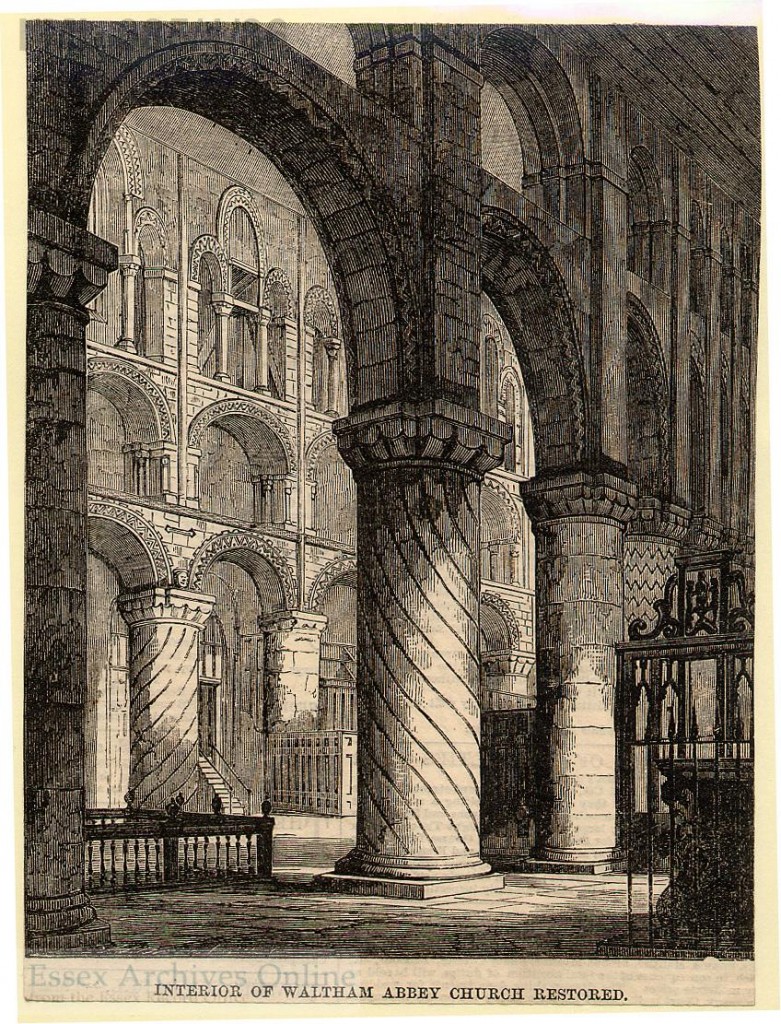

It’s also interesting to read that Roger de Mescinges was giving his land to his son-in-law because his own body was ‘so debilitated’ that it was not possible for him to defend his land, labourers and possessions. Land and with it wealth and possessions were held by those able to physically defend it. After nearly three years of civil war, with a great deal of fighting taking place in Essex, Roger de Mescinges had decided that a younger man was needed to defend his land.

Find out more about Essex connections with the Magna Carta with us on Saturday 23 May.

Magna Carta: Essex Connections

To explore the significance and legacy of this famous document, both nationally and for Essex, join us for talks from:

- Nicholas Vincent, Professor of Medieval History at the University of East Anglia, who has been leading a major project researching the background to Magna Carta

- Katharine Schofield, ERO Archivist, on Essex connections with Magna Carta and the impact it had on the medieval county

Saturday 23 May, 1.15pm for 1.30am-4.15pm

Tickets: £8, including tea, coffee and cake

Please book in advance on 033301 32500